Part II.

Supporting Workers and Protecting Families

By Brink Lindsey & Samuel Hammond

In this chapter:

Shift to Level Targeting in Monetary Policy

Comprehensive Social Insurance Modernization

Employment Security and Workforce Development

Strengthen Families with Child Allowances

Fix Health Insurance with Universal Catastrophic Care

In January 2020, Taco Bell began advertising $100,000 salaries for general managers at certain locations. [1] The generous pay was an experiment driven by the tightest labor market in a generation, and a striking example of the boost full employment gives to workers’ bargaining power. Business complaints about labor shortages were finally giving way to wage increases as the only way to attract and retain talent. And with the unemployment rate below 3.5 percent, wage growth within the bottom quarter of earners was the fastest seen in over a decade. [2]

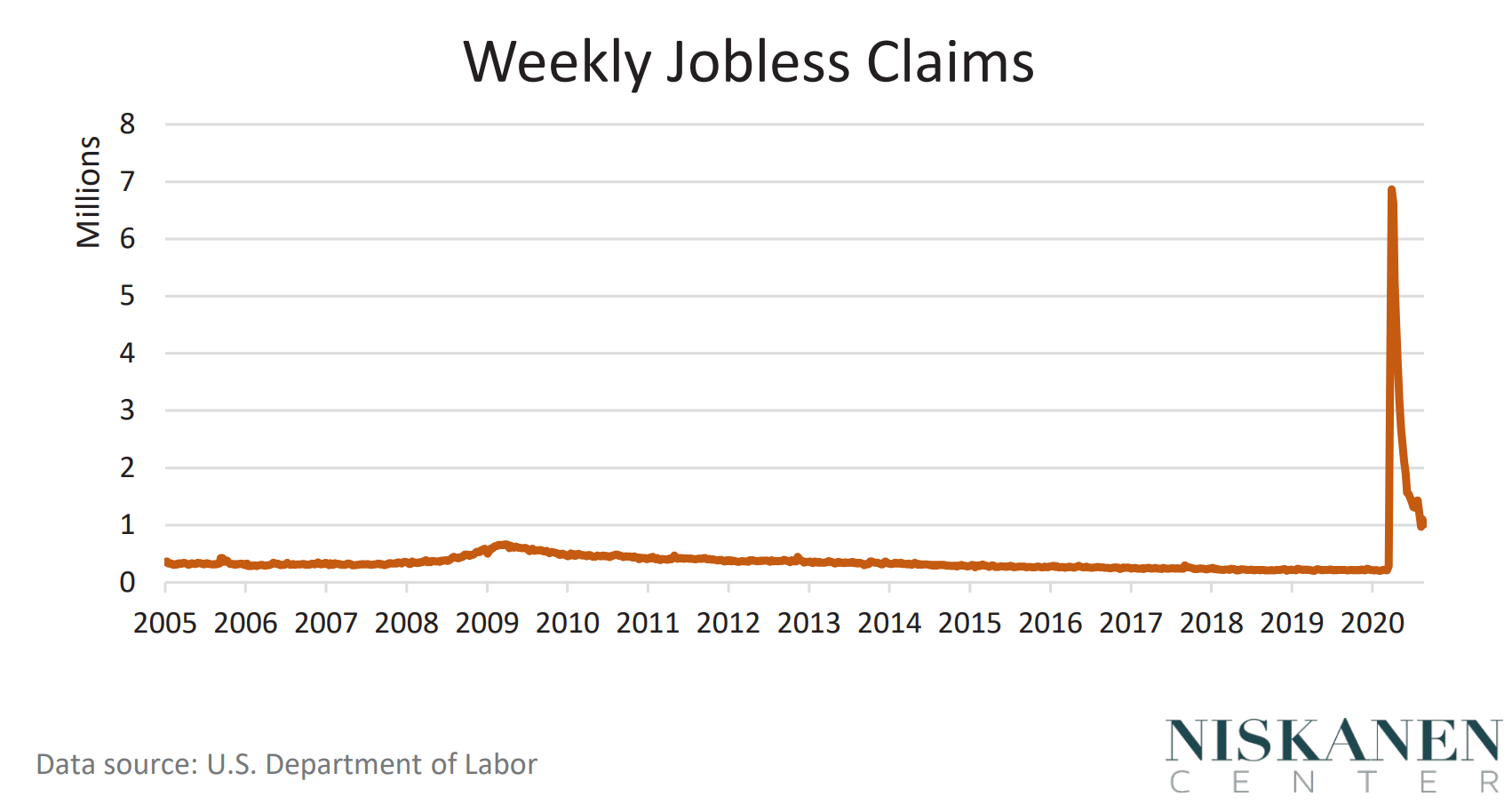

How quickly things change. As a direct consequence of the COVID-19 public health crisis, quarantine orders and business shutdowns have pushed upwards of 30 million Americans into joblessness in the first eight weeks of lockdowns alone. [3] The April 2020 jobs report revealed an official unemployment rate of 14.7 percent, the highest on record since the Great Depression. The U6 unemployment rate, which includes discouraged and underemployed workers, reached a staggering 22.8 percent. Yet even this understates the severity of the situation, as a 2.5 percentage point contraction in the labor force pulled the participation rate to its lowest point since January 1973. [4]

Subsequent reports have indicated some job growth, however these overwhelmingly represent workers returning from temporary layoffs or furloughs as businesses begin to reopen. [5] Time will tell whether the surge in infections after Memorial Day, combined with the expiration of more generous relief spending, will render these apparent signs of recovery premature. Regardless, according to an analysis of the monthly Current Population Survey, the May 2020 unemployment rate among workers in occupations that pay $500 or less per week was 27 percent. This contrasts with the 6.9 and 4.8 percent unemployment rates within occupations earning $1,000-$1,500 per week and above $1,500 per week respectively. In other words, the Great Depression has arrived, it’s just not evenly distributed. [6]

In the best-case scenario in which the virus is brought under control and quarantine measures subside, many of these predominantly low-wage service sector jobs will return. Many more workers, however, will reenter the labor market to find that their former employer has gone out of business, or that their particular job is simply no longer in demand. [7] It is hard to know in advance how many fall into that latter category. Nonetheless, a recent analysis by Bloomberg Economics suggests 30 percent of U.S. job losses from February to May were the result of a “reallocation shock,” meaning upwards of one in three of those newly out of work will need to retrain or relocate. [8] Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell expressed a similar concern in a June news conference when he noted that there may be “well into the millions of people who don’t get to go back to their old job … In fact, there may not be a job in that industry for them for some time.” [9]

If nothing is done to minimize the frictions associated with a labor reallocation of this magnitude, a substantial fraction of dislocated workers will eventually become discouraged and leave the labor market altogether. The rest will begin the costly process of job search and retraining, in a tango with employers whose business models will likewise need to reset around the new, uncertain normal. In lieu of finding a better job match in time to pay the bills, many workers may end up settling for a lower-paying job than they had before, worsening income inequality and productivity growth simultaneously.

America’s hot labor market may be gone, but it is not forgotten. As the U.S. economy reopens, returning to full employment should be a top priority. At the same time, the quality of the jobs created in the pandemic’s wake matters just as much as the quantity. Creating millions of new low-wage jobs with minimal security or stability and few pathways for career advancement would be at best a Pyrrhic victory. Instead, now is the time to reexamine the policy choices that left so many low-wage workers vulnerable to dislocation in the first place, and enact the reforms necessary to put the U.S. economy on a high road, high performance path going forward.

Merely removing the work disincentives embedded in current policies will not be sufficient, either. While much ado has been made about pandemic unemployment assistance exceeding prior wages, for example, this is the least of our concerns. [10] The expansion is only temporary, and besides, the main tradeoff associated with larger and longer-lasting unemployment benefits is between budgetary cost and optimizing labor-market matches:

Spending more allows workers to take the time to search for the jobs that best match their skills; spending less risks forcing the unemployed to settle for any kind of paycheck. [11] A large reallocation shock like the one caused by the pandemic is thus precisely the scenario under which the social cost of generous unemployment benefits is lowest. But more importantly, supply-side incentives are only half the equation. Ultimately, the dramatic collapse in employment during the pandemic stemmed from a collapse in labor demand, as entire swaths of the economy closed up shop. A robust recovery is therefore impossible without a strategy focused on restoring labor demand.

As we detail in the sections below, the road to full employment begins with a revamp of U.S. monetary policy, which for decades has been biased in favor of persistent labor market slack. Next, we argue for overdue modernizations to our existing social insurance systems, including aggressive Active Labor Market Policies (ALMPs) to smooth job transitions; child allowances to support families and sharply reduce childhood poverty; and universal catastrophic coverage to expand access to health care while constraining costs. With this combination of reforms, we can choose to make full employment the rule rather than the exception. We can exit this crisis with stronger labor market institutions than we had going in, moving forward on a new high road of broadly shared prosperity.

Shift to Level Targeting in Monetary Policy to Minimize Economic Slack

For any agenda to improve conditions for inclusive economic growth, monetary policy is a logical starting point because its effects are so pervasive. Mess it up, and that failure alone will sabotage everything else you do right.

What does it mean to do monetary policy well? The goal for central bankers is to keep growth going as fast as is consistent with the underlying endowments of population, technology, and the rest of public policy—in other words, to ensure that actual output aligns with potential output. Like a bidder on “The Price Is Right,” you want to get as close as possible to your target without going over.

Good monetary policy, then, must navigate between risks on either side. If you undershoot and are too restrictive, you could stall the economy outright and induce a recession; alternatively, you could hobble economic performance well short of its potential, leaving employment opportunities and welfare gains on the table — and possibly degrading the economy’s potential output in the process. If you overshoot and are too lax, you could overheat the economy and create bubbles followed by an inevitable bust, or you could unleash inflationary pressures that then are extremely costly to contain. It’s no wonder, then, that allusions to Goldilocks crop up again and again: You want your monetary policy not too hot, not too cold, but just right.

Unfortunately, in recent decades U.S. monetary policy has regularly erred on the side of excessive restrictiveness. The result has been millions of forgone jobs, a huge and lasting wipeout of personal wealth, and very possibly depressed dynamism and productivity growth.

This failure has been obscured by the very low interest rates we’ve experienced since the Great Recession. Given that the Federal Reserve’s favored method of monetary stimulus is to target a reduction in the federal funds rate, the conventional wisdom associates low rates with easy money. That conventional wisdom, though, is flatly wrong. On the contrary, low rates are a sign that money has been tight (rates were very low during the Great Depression as well as now), while high rates are a sign that it has been too loose (rates were very high during the Great Inflation of the 1970s). [12]

Notwithstanding this confusion, the evidence of excessively tight money over the past decade is there for all to see. In particular, since the Great Recession, inflation has regularly fallen short of its target rate of 2 percent. This failure is not due to a lack of ammunition on the Fed’s part; in fact, the Fed moved to raise rates repeatedly – that is, to tighten – nine times between December 2015 and December 2018. The Fed began raising rates after the unemployment rate first dipped below 5.1 percent, which at the time was considered the lowest level consistent with price stability. But unemployment kept falling, all the way to 3.5 percent, without any surge in inflation. The Fed has thus moved repeatedly to revise downward its estimate of the “natural” (lowest noninflationary) unemployment rate. In other words, the Fed made a mistake, tightening money in response to a nonexistent inflation threat. As Fed Chair Jerome Powell admitted, “policy was less accommodative than thought at the beginning of normalization.” According to one estimate, the cost of that mistake as of August 2018 was between 0.4 and 0.8 percent of lost GDP and between 530,000 and 1 million lost jobs. [13]

Looking beyond the record of the current expansion, there is persuasive evidence that monetary policy has tended to be overly restrictive for decades now. Comparing the actual unemployment rate to the Congressional Budget Office’s estimate of the natural rate, there has been slack in the U.S. labor market for roughly 70 percent of the quarters since 1980 – as compared to about a third of the quarters from 1949 to 1980. [14] This bias toward tightness appears to be a case of generals’ fighting the last war: After allowing inflation to get out of control in the 1970s, policymakers since then have tended to lean too far in the other direction.

But the American economy has changed dramatically since the days of disco and leisure suits, and the macroeconomic challenges we face now are altogether different. In February, the unemployment rate stood at 3.5 percent, and the annual federal budget deficit clocked in around 5 percent of GDP. From the perspective of the 1970s, or any other period of American economic history for that matter, these numbers suggest a white-hot economy overdosing on fiscal stimulus. Yet core inflation was still hovering around 2 percent, and the entire yield curve on government bonds – all the way out to 30 years – was, and remains, below 1 percent. Whether or not “secular stagnation” is the technically correct diagnosis, the fact is that demand has barely kept pace with the economy’s productive potential even with a high degree of fiscal stimulus; and given rock-bottom interest rates, the conventional tools of monetary stimulus are running up against their limits. Indeed, despite the Fed being among the more competent government actors during the pandemic, the extraordinary measures it has taken have mostly served to prevent deflation and an all-out economic collapse. Thus, as of this writing, the bond market is forecasting inflation to average only 1.3 percent for at least the next 10 years. [15] Things could always be worse, but that is still well below target.

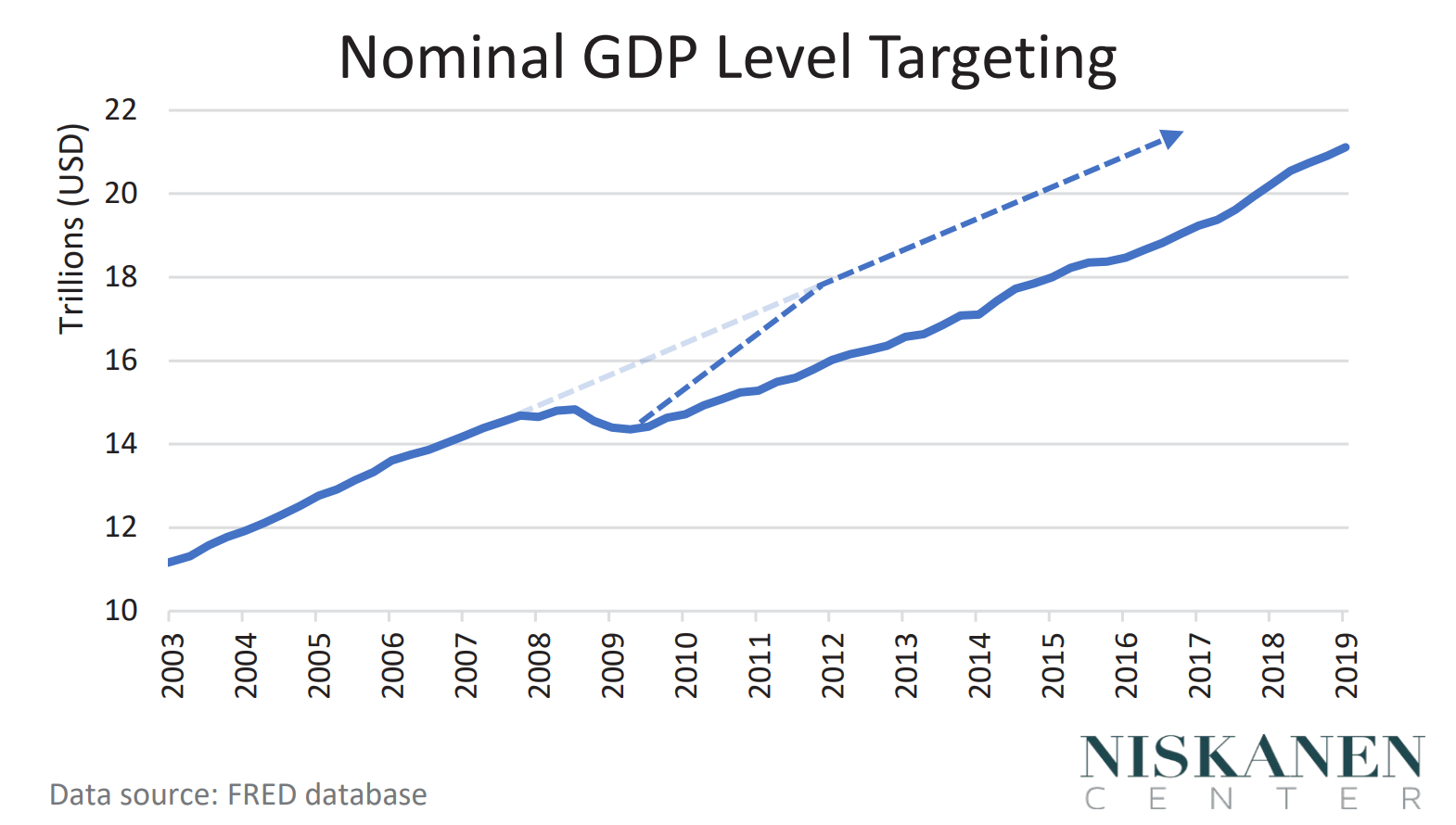

Accordingly, we believe the time has come for a regime change in U.S. monetary policy. The current regime consists of inflation rate targeting (although in recent years that target has seemed like more of a ceiling) via moves in the federal funds rate; in its stead, we propose a shift to level targeting. In the current conditions of weak demand, level targeting is much more conducive to realizing the economy’s actual productive potential than the present approach due to one key feature: It requires the Fed to make up for past mistakes. With inflation-rate targeting, if the Fed fails to meet the 2 percent target one quarter, it simply tries again the next quarter without doing anything to compensate for the prior shortfall. Consistent undershooting, as we saw in the aftermath of the Great Recession, leads to a growing gap between actual and potential output.

With level-targeting, by contrast, if the Fed falls short while targeting inflation of 2 percent a year, it will need to target a higher rate of inflation in the ensuing period to catch back up to the intended level-growth path. We note that the Fed’s recent announcement of a policy shift to “average inflation targeting” represents a welcome step in this direction, giving the Fed flexibility to pursue higher inflation when it fails to meet its target in the prior period. [16] Whether and how much this flexibility will actually be used, however, remains to be seen. In our view, an explicit commitment to a price level target would be preferable.

Although a price level target would represent a big improvement over the status quo, we believe that nominal GDP (NGDP) targeting is a superior alternative over the longer term. This is because the price level can be affected by both demand shocks and supply shocks (either positive, as in the case of a surge in productivity, or negative, as in the case of an interruption in oil supplies). When central banks fail to differentiate between supply- and demand-driven shocks, they can be led astray. Tightening in the face of a spike in oil prices, or loosening in the face of a productivity surge, would be procyclical, exaggerating the effects of a negative supply shock in the former case and overheating the economy in the latter. Conversely, when the target is a rising level of total nominal spending, the need to sort out whether a supply or demand shock is driving the change in the price level is eliminated. [17]

For illustration, suppose the annual level target for NGDP was set at 4 percent (the exact number chosen is of secondary importance), [18] composed of a real component (GDP) and a nominal component (inflation). So long as the Fed remained committed to a 4 percent annual rise in NGDP, the split between NGDP’s real and nominal components would be able to shift freely. In the presence of a negative oil supply shock, for example, real GDP would contract and inflation would rise, perhaps shifting from 2 percent each to 1 percent and 3 percent, respectively, thereby keeping aggregate spending stable. This feature of NGDP level targeting would be particularly useful in a recession like the one sparked by COVID-19, given the impossible challenge of decomposing a shock that affects supply and demand simultaneously.

An NGDP level target would also provide a superior anchor for long-run price stability consistent with full employment, making it an ideal match for the Fed’s dual mandate. This is because many long-term contracts, such as home mortgages, are written in nominal dollar terms, e.g., “I will pay you X dollars for Y asset at some point in the future.” Under the current inflation-rate targeting regime, one can be relatively certain that the overall price level will be roughly 2 percent higher in the following year, give or take several tenths of a percent. Yet those “give or takes” add up over time, effectively un-anchoring one’s best estimate of the price level 20 or 30 years hence. With a price level target, in contrast, one only needs a back-of-the-envelope calculation to deduce the likely real value of a nominal contract indefinitely into the future.

NGDP level targeting just extends this insight one step further, by noting that an economy’s aggregate contractual obligations are ultimately met not in terms of prices, but in terms of total dollar income — the price level times the real underlying production. Here a “musical chairs” analogy illuminates the benefits of NGDP level targeting. [19] If the market as a whole implicitly expects total dollar incomes to roughly double in 20 years (given by the nominal value of contracts that will come due), allowing NGDP growth to fall short of expectations necessarily implies that somebody, somewhere in the future will have too few dollars to meet their obligations — as if the music stopped with several chairs removed. [20]

Through this lens, a demand-side recession is simply what happens when actual NGDP falls sharply relative to expectations, resulting in a sudden mismatch between aggregate income and promised wages. Were the Fed committed not just to meeting a target for nominal income growth over a given year, but also to making up for past mistakes, any deviation below the target NGDP growth rate — a signal of monetary tightening — would itself signal equal and opposite monetary easing over the year ahead. In that sense, level targeting represents the ultimate “automatic stabilizer.”

A change in the monetary regime to level targeting should lead to much more rapid recovery from recessions than we have experienced of late, while ensuring that actual economic growth throughout an expansion lives up to the economy’s productive potential. Since temporary shortfalls in output can translate into permanent shortfalls through hysteresis (e.g., workers lose skills during prolonged unemployment and thus are less productive when they eventually return to work), keeping output growth humming at full potential improves long-term growth prospects as well. Evidence is accumulating that the Great Recession and its aftermath caused a significant decline, not only in actual output, but in potential output as well. [21] Moving to level targeting would ensure that future recessions don’t inflict this kind of permanent damage.

In addition to avoiding losses from hysteresis, level targeting could also improve the economy’s long-term potential by boosting productivity growth. When appropriate monetary accommodation wrings slack out of the economy and keeps labor markets relatively tight, employers have sharpened incentives to invest in labor-saving – i.e., productivity-enhancing – innovations. By contrast, slack labor markets depress wages and thereby encourage businesses to maintain or expand more labor-intensive ways of doing things. Keeping the economy at or near its potential in the short term may therefore also help to raise that potential over the long term. [22]

While promoting high performance through maximizing growth prospects, a level targeting regime would also provide high-road uplift through its distributional consequences. Tight labor markets are workers’ best friend: wages are higher, wage growth is more rapid, and hours worked go up when the overhang of unemployed and discouraged workers is minimized. Moreover, the benefits of tight labor markets flow disproportionately to workers on the lower end of the pay scale. [23] Over the past several decades, the only times when the U.S. economy has seen significant wage growth for ordinary workers were the late 1990s and the past couple of years – which, not coincidentally, were periods of record-low unemployment. These episodes of widespread prosperity stand out as exceptional, but there is no reason they couldn’t be the norm. Well-designed monetary policy can work to expand the economic pie while at the same time ensuring that workers get a bigger slice.

Comprehensive Social Insurance Modernization

The economic calamity facing workers and businesses amid the COVID-19 crisis is not unique to the United States. Most advanced countries are experiencing similar disruptions and have enacted relief measures of their own. Nor was the U.S. Congress particularly stingy in its response, at least at the outset. On the contrary, the relief measures enacted by Congress in the first months of the crisis were, at least in dollar terms, among the most aggressive in the world (even if one cannot say the same about our public health response).

Instead, what has set the U.S. economic response apart can largely be attributed to the failings of our existing social insurance infrastructure. In the earliest weeks of the crisis, for example, every Thursday smashed the pre-pandemic record for weekly jobless claims by an order of magnitude. With millions of people being laid off across the country, our labor market has never hemorrhaged jobs so quickly, and one prays that it never will again. Yet despite the generosity of the CARES Act’s emergency relief provisions, implementation was hindered from the start by one technological anachronism after another. [24] State unemployment offices were overrun by hundreds of thousands of applications, crashing websites and creating lines of (potentially contagious) workers that stretched around the block. As of mid-July, mere weeks before the original $600-per-week Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC) was set to expire, nine U.S. states had still not reported a single claim for benefits. [25]

The implementation of the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) wasn’t much better. The program enlists banks to provide businesses with fewer than 500 employees, as well as hotel and restaurant chains, with forgivable loans for 2.5 months of average payroll and some operating costs. While laudable in its ambition, PPP faced immediate technical difficulties. To apply for federally guaranteed loans, banks had to submit completed applications through an online portal called E-Tran for processing by the Small Business Administration (SBA). [26] Much like state UI systems, E-Tran was flooded by applications the day the program launched on April 3, causing outages that meant many banks — including more than a third of community banks — were unable to access the system at all. Given the “first-come, first-served” nature of the available funding, the program prompted a run to the banks that could access it, and thus ultimately favored lenders with the best IT departments and businesses with the savviest accountants. Access to E-Tran remained sporadic until the SBA enlisted Amazon Web Services to launch a new online gateway on April 8, about a week before the program initially ran out of money. [27] Between these technical barriers and design flaws inherent in the program itself, the industry with the least exposure to job losses — professional, scientific, and technical services — was ironically among the largest recipients of payroll relief. [28]

It is sometimes said that, whatever other problems plague the public sector, governments are at least efficient at cutting checks. If only that were the case in the United States. Indeed, while the CARES Act’s $1,200 “Recovery Rebate” went out faster than many expected and with a phenomenally low error rate, the conceit that this transfer payment was really a “tax credit” stymied the Treasury Department’s ability to reach the millions of low-income households that rarely file federal tax returns. [29] Rather than link federal administrative data to state databases containing household information on Medicaid and SNAP recipients, allowing the majority of nonfilers to receive their payment automatically, Treasury instead took days building a buggy online application. As Marc Andreessen noted in his widely shared essay, “It’s Time to Build,” written in a bout of anger and frustration, “A government that collects money from all its citizens and businesses each year has never built a system to distribute money to us when it’s needed most.” [30]

How did we let this happen? Social insurance systems are ultimately a kind of public infrastructure, and much like our roads and bridges, they require continuous repair. Take America’s federal-state UI system, which dates back to 1935. UI is supported by a combination of state and federal employment taxes, but the federal wage base is not indexed to inflation. Accordingly, appropriations for state UI administration reached a 30-year low in 2017, [31] even as the maintenance cost of state UI programs escalated. Most state UI programs run on architecture constructed in the 1960s using Fortran and COBOL programming languages created for the “punch card” era of early mainframe computing. Such programming languages work perfectly fine and even have some benefits — until you need to change them. [32] The UI expansion under the CARES Act thus set off a hunt to find any of the dwindling number of coders fluent in the programming equivalent of Latin: a dying language kept alive due to its niche, if potentially salvific, applications.

A depressingly similar story applies throughout the U.S. government. Where we chose to support payrolls through a Rube Goldberg device of forgivable small-business loans, many countries opted to subsidize payrolls directly, including Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, the U.K., and Canada. Proposals to do the same here, advanced by Republican Sen. Josh Hawley and Democratic Rep. Pramila Jayapal, were shot down as too radical, despite amounting to a cleaner version of what was adopted instead. [33] The choice to embed a transfer program in a financial product ultimately gives credence to the tradeoff between social insurance and financialization proposed by sociologist Monica Prasad. [34] In the aftermath of World War II, the United States diverged from Europe by promoting easy credit over more direct systems of social insurance. Both models resulted in a substantial middle-class welfare state, with the main difference being the degree to which America’s redistributive policies are subterranean — a legacy that can be seen to this day in our limited social expenditures relative to household indebtedness. [35] These back-door mechanisms of social support are also incredibly difficult to navigate, both for beneficiaries and administrators – a problem that even the best technology will not solve, and sadly, one that opponents of the robust welfare state repeatedly seek to exploit.

Thus, in the quest to build a high performance social insurance system, modern IT infrastructure is only a necessary, not sufficient, condition. Consider that Florida is among the 16 states that have “fully modernized” their UI programs in terms of IT, but was nonetheless one of the most problematic states in terms of CARES Act implementation. [36] This is because Florida’s previous government saw modernization as a means of reducing the growth in UI rolls following the Great Recession, and thus deliberately redesigned the program to make filing claims a bureaucratic nightmare. A parallel story occurred in Michigan, where modernization was used to flag and penalize fraud at unprecedented levels through a system called MiDAS. As National Employment Law Project Executive Director Rebecca Dixon noted in recent testimony before the House Budget Committee,

"The MiDAS system flagged more than 40,000 workers for fraud, and it was 93 percent inaccurate. The penalty for fraud in Michigan is four times the amount paid, plus 12 percent interest. As a result of these false flags, innocent claimants lost everything, including homes, and in severe cases, lives."" [37]

Michigan subsequently shifted course to become “one of the fastest states in terms of payment processing.” [38] Nonetheless, these examples show that the success of IT modernization depends on the orientation of underlying policies and a willingness to iterate on program design.

Modernizing our social insurance systems has the potential to save money in the long run while reducing a variety of administrative burdens. But just as important, superior technology will enable the implementation of different kinds of policy designs, from the mundane to the experimental. The CARES Act, for example, set pandemic unemployment compensation at $600 per week because pegging the benefit to 100 percent of prior wages was technologically infeasible for most states. Modern systems would make such design choices trivially easy to implement, while expanding the horizons for innovative ideas such as return-to-work bonuses, as we discuss in the next section. Similarly, the U.S. Treasury has existing financial pipes to virtually every employer in the country, given employer obligations to record and remit federal payroll taxes on a monthly or biweekly basis. There is nothing that prevents those pipes from being put in reverse in order to advance payroll rebates directly to employers, particularly if they use any of the large payroll processing firms. It would take some effort, but with far less arbitrariness and complexity than what went into the PPP.

Going forward, we support an all-of-government effort to modernize our outdated social insurance systems. This will require comprehensive reforms at multiple levels, along with a major boost to the federal government’s paltry Technology Modernization Fund (TMF). Created in 2017, the TMF provides flexible funding for IT modernization proposals submitted by other federal agencies. [39] Proposals are rigorously evaluated but can be quickly approved, with follow-on funding tied to delivery on project milestones. But with only $25 million in resources for fiscal year 2019, the fund is woefully undercapitalized given the sheer size of the U.S. government. Virginia Rep. Gerry Connolly has proposed boosting the fund to at least a billion dollars, which to us sounds about right. [40]

Nevertheless, funding for IT modernization will be of little use if the federal government is unable to hire the best people for the job. Take the IRS, which is already engaged in a multiyear modernization initiative, but whose progress reports have been lacking. Disturbingly, an internal team of programmers was on the cusp of migrating the IRS’s all-important Individual Master File (the system used to store and process tax submissions) from impenetrable assembly code into a modern programming language, until they inadvertently allowed the chief engineer’s employment contract to lapse in 2018. [41] As was reported at the time, the software engineer in question had been “working under streamlined critical pay authority the agency has had since its landmark 1998 restructuring.” [42] The authority provided the IRS with 40 slots under which it could pay temporary, full-time employees with salaries that exceed the pay scale used for career employees — until Congress failed to reauthorize the slots in 2013. Stories like this do not make the nightly news, and yet they are critical to understanding the roots of America’s diminished state capacity.

Fortunately, the IRS’s critical pay authority was finally renewed as part of the 2019 Taxpayer First Act. [43] Unfortunately, the bill only passed once a provision was added to enshrine the IRS’s Free File system, which allows most Americans to file for free – but only through private tax preparation companies like Intuit and H&R Block. [44] Preventing the IRS from creating its own tax-preparation service itself represents a tax on the American public, as the vast majority of taxpayers have returns that require minimal preparation. [45] Indeed, the IRS has all the information it needs to calculate most of our taxes, send out a pre-populated return, and let us decide whether to pay the bill or file an alternative. [46] On the path towards a 21st-century tax and transfer system, it seems the United States took one step forward, but two steps back.

Employment Security and Workforce Development

In the previous section, we made the case for modernizing our systems of social insurance through an analogy to other kinds of public infrastructure. That need has only become more urgent as COVID-19 pushes existing systems to their breaking point, like a congested bridge on the verge of collapse. Yet with new infrastructure come new possibilities. A crumbling highway can be repaired, or it can be rebuilt with greater structural integrity and new lanes added. The same is true of our social insurance system, and of Unemployment Insurance in particular.

Consider paid sick leave. Being able to take paid time off work when you’re sick is one of the many perks of being a salaried worker. Yet as the COVID-19 crisis has underscored, sick leave is not merely a nice thing to have, but also a critical form of public health infrastructure for reducing the transmission of contagious diseases among one’s co-workers and the broader public. Within the U.S. civilian labor force, the Pew Research Center estimates that 33.6 million workers lack access to any form of paid sick leave. [47] While almost universally available to high-income workers, paid sick leave is provided to only one in two workers in the bottom quarter of the wage distribution, and to just 43 percent of all civilian part-time workers. Ironically, these also tend to be the workers for whom every paycheck goes toward affording rent and other necessities, making unpaid leave either untenable or, at the very least, an option that’s only reluctantly taken after symptoms worsen. This is bad enough in normal times, but in the context of a pandemic it’s unconscionable.

Recognizing the problem, Congress mandated private employers with fewer than 500 employees to provide two weeks of paid sick leave in the Families First Coronavirus Response Act. Unfortunately, the only partially funded mandate had the unintended consequence of incentivizing layoffs in advance of its enactment. Utah Sen. Mike Lee opposed the bill for this reason, arguing that sick leave could be more efficiently provided through UI. [48] We agree: With a modernized UI system, we could guarantee baseline paid leave for every worker in the country, while minimizing the impact on businesses.

A modern UI system would further enable work-sharing programs to reach their full potential. Work-sharing helps employers avoid layoffs during a temporary downturn by letting workers offset reduced pay or hours with a partial UI benefit. [49] The norm across much of Europe, work-sharing has allowed many countries to avoid the enormous COVID-19 induced layoffs seen in the United States. [50] And while many U.S. states have work-sharing programs in place, employer participation is undermined by administrative complexity and taxes that discourage its use — two things modernization could address. [51]

Indeed, with millions of people out of work, a large fraction of the unemployed will need to retrain or relocate. Better fiscal and monetary policy can help, but only so much, as a “reallocation shock” ultimately requires costly adjustments within the real economy. [52] A well designed UI system should be designed to help, rather than hinder, those adjustments — to ease frictions rather than create new frictions where they needn’t exist.

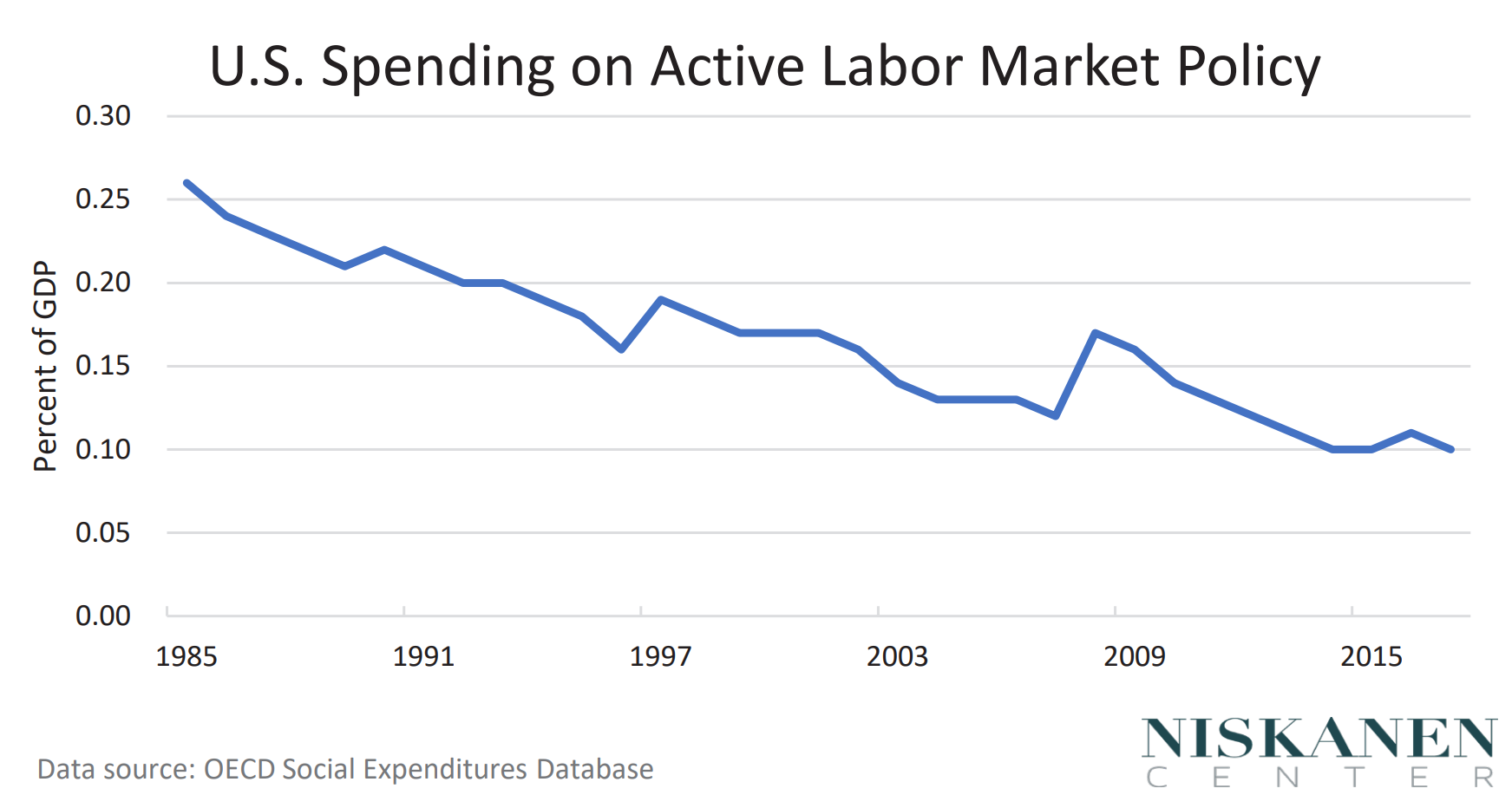

In particular, the United States lags far behind the rest of the developed world in its use of active labor market policy (ALMP). ALMPs serve to boost labor force participation and support for workers through job transitions, and encompass everything from retraining programs to job search services. According to the OECD, the United States spends only 0.10 percent of GDP on ALMPs, the lowest of any OECD country after Mexico. Anglophone countries like Canada and Australia expend much less on ALMPs than European social democracies, but still double what the U.S. does. The United States would need to increase spending on ALMPs by nearly $100 billion per year just to match the OECD average of 0.52% of GDP. [53]

As the Council of Economic Advisers noted in a 2015 report, our low expenditure on ALMPs is the result of a steady erosion that began in the 1980s, and it correlates with a subsequent decline in prime-age labor force participation. [54] In his book, Failure To Adjust, Edward Alden attributes our underinvestment in ALMPs to the historical dominance of the U.S. economy relative to the rest of the world. [55] The size of the U.S. internal market provided an intrinsic buffer against external shocks, but also a high degree of geographical and economic diversification, making it difficult for the shocks that did occur to garner the political recognition needed to motivate comprehensive reforms. In contrast, a small, open economy like Denmark spends over 1.9 percent of GDP on ALMPs because its greater exposure to external shocks creates broad support for programs that retrain and reallocate labor on a continuous basis.

As of 2017, America’s ad hoc approach to reemployment has resulted in the proliferation of at least 43 distinct but largely duplicative federal employment and training (E&T) programs. [56] The largest such program is Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA), which was historically expanded in the context of new trade agreements. TAA singles out for reemployment support only those workers who can demonstrate that their job was destroyed due to international competition or outsourcing. Of course, establishing that kind of causation is a challenge for the world’s top econometricians, much less your typical blue-collar worker. [57] Consequently, administrative data show that every trade-displaced worker accepted into TAA is associated with two lost jobs overall, implying America’s single largest retraining program is barely covering its own relatively narrow remit. [58]

More important, the economic rationale for reemployment support is independent of why a given labor market shock occurred, whether due to trade, technology, a recession, or for that matter a pandemic. Indeed, as economists are fond of noting, international trade is in key respects indistinguishable from a “black box” technology that lets you magically turn American corn into Japanese cars. [59] America’s employment and training system should be just as agnostic to the causes of labor market disruption, and thus available to the universe of dislocated workers through a comprehensive workforce development system that interfaces with UI.

What would such a system look like? To start with, state UI programs should be required to replace at least 75 percent of lost wages up to the median wage. This would require standardization of how each state calculates weekly benefits [60] and would bring U.S. benefit levels closer to the OECD norm. In 2019, for instance, the average UI recipient nationwide received $378 in weekly benefits, replacing just shy of 50 percent of prior wages. Yet this average is skewed upward by the policies of the most generous states. In many states, average replacement rates are closer to one-third of prior wages and have further eroded following the Great Recession as multiple states cut their UI programs to close budget gaps. In a 2013 reform, for example, North Carolina cut its maximum unemployment compensation to just $350 a week, while shortening the maximum duration from 26 weeks to just 12 weeks. [61] As a result, the rate at which recipients exhausted their benefits before finding new employment rose dramatically. This is obviously short-sighted. Rather than promote work, small benefits and restrictive eligibility can cause dislocated workers to become discouraged and exit the labor force altogether. Worse still, some may fall back onto programs like disability insurance that condition benefits on not working, as occurred in labor markets affected by the China Shock. [62] A high wage-replacement rate, in contrast, serves to smooth household consumption following a shock, while ensuring the path of least resistance for dislocated workers is a system that keeps them attached to the labor force.

A high wage-replacement rate must be balanced with activation policies – conditions requiring the unemployed to prepare for returning to work – that limit abuse, as well as a strategy for triaging employment and training services to those who need them most. In a normal year, some 7 million jobs are both created and destroyed in the United States every quarter. That balance of creation and destruction ensures the vast majority of laid-off workers are able to find suitable employment all on their own. And for the fraction that turn to UI, the median duration is less than 10 weeks, with a third of workers finding a new job in under five weeks. [63] This cohort typically requires minimal activation beyond standard work search requirements, and only basic supportive services like help preparing a resume or navigating a job bank.

Stricter benefit conditionality begins to make sense beyond 5-10 weeks of unsuccessful job search, beginning with an in-person interview. In Nevada, for instance, UI recipients are eventually required to meet with trained staff at “One Stop” job centers located across the state for what’s known as a Reemployment and Eligibility Assessment (REA). During the assessment, claimants are provided with labor market information and develop an individual reemployment plan. If it makes sense in the individual’s case, the same caseworker can also provide a referral for reemployment services, training, or a job placement. A Spanish speaker, for instance, may simply need language services, while a single parent may need help finding child care. This modest requirement thus helps Nevada triage resources more effectively, while generating net savings through reduced UI payments. In a rigorous evaluation, Nevada’s REA program was even found to increase earnings per claimant by 15–18 percent over the study’s 18- to 36-month follow-up period. [64]

Most states have an REA-type program in place, supported by grants from the federal Department of Labor. [65] We support building on the program to ensure every state reemployment program is adequately funded, following best practices, and fully integrated with local workforce-investment boards. In many states, for instance, REA programs are used to direct workers into growing industries, thereby contributing to regional economic development. [66] Nonetheless, these simple interventions will still leave some workers behind, including those facing structural barriers to employment and skilled workers whose industry is in decline. These cases require more concentrated support, whether in the form of subsidized job placements, retraining, or both.

While classroom-based retraining programs are notoriously ineffective, state and local workforce boards can work with large employers to develop programs that reflect in-demand skills. Subsidized job placements go a step further, facilitating quick transitions out of unemployment by offsetting several months of an employer’s wage- and on-the-job training costs. Subsidized employment programs were piloted throughout the country following the Great Recession, and were found to be highly effective at promoting high-quality job creation and retention — particularly when an employer’s eligibility for subsidies depends on providing decent wages and working conditions. [67] We therefore favor replacing the myriad federal retraining programs with a new Employment and Training title to the Social Security Act, providing states with dedicated funding to scale up subsidized employment and retraining programs with a solid evidence base. In line with the ELEVATE Act introduced by Oregon Sen. Ron Wyden in 2019, the level of federal funding could even be pegged to a state’s unemployment rate, thus creating aggressive and fast-acting “automatic stabilizers” that directly target labor demand. [68]

In simple economic models, workers disrupted by trade or automation are instantly reallocated from declining industries to ones on the rise. Yet that is rarely if ever the case in the real world. Labor markets are highly complex institutions, riddled with frictions created by geography, social networks, discrimination, and regulations that vary from place to place. In a world where nothing ever changes, this wouldn’t be a big problem. Yet in a dynamic, growing economy, change is the rule. America deserves a workforce development system that reflects that basic reality.

Strengthen Families with Child Allowances

Our vision for a high-wage, high-performance economy would be incomplete without an agenda for supporting strong families and healthy children. It may be cliché, but family truly is the foundation of society. Rich or poor, big or small, traditional or modern, families are responsible for nurturing the next generation.

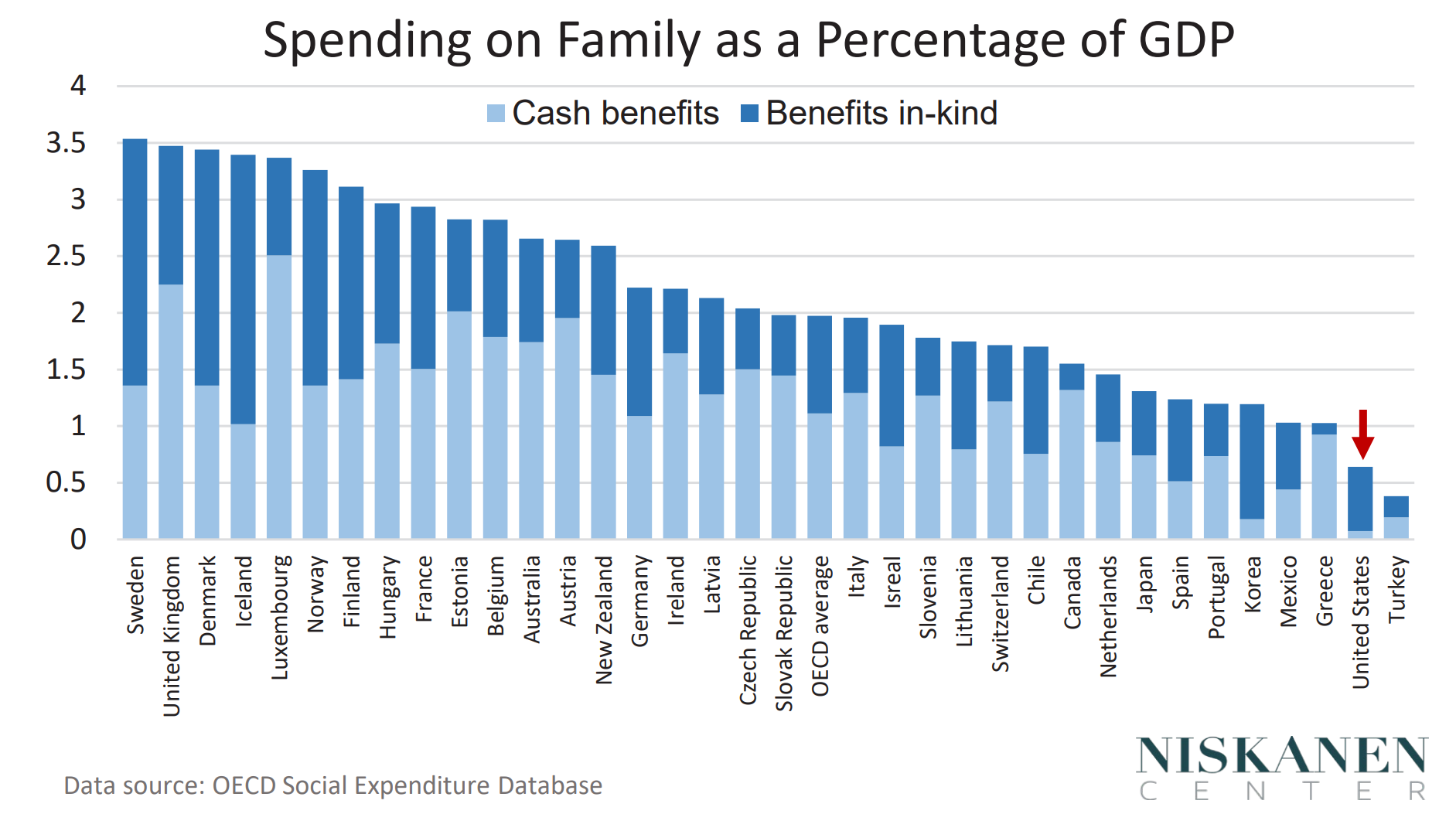

Unfortunately, of the four million children born in the United States every year, one in six begins life in poverty. Indeed, the United States has one of the highest rates of child poverty in the developed world. When one looks across the OECD, the reason why becomes obvious: our lack of direct expenditures on families and children. [69]

The United States spends only 0.7 percent of GDP on family social expenditures, of which the share devoted to cash benefits, 0.1 percent, is the lowest of any OECD country. [70] The United States would need to increase cash transfers to families by approximately $200 billion per year simply to match the cash portion of the OECD average. Accordingly, increasing direct cash transfers to households with children is far and away the lowest hanging fruit when it comes to reducing child poverty.

This is why we are strong supporters of the American Family Act — a proposal to transform the existing Child Tax Credit (CTC) into a bona fide child allowance. [71] Since its enactment in 1997, the CTC has become an essential tool for supporting the well-being of children and working-class families. And yet, because it is only partially refundable, the full credit remains out of reach for the poorest families. The American Family Act would change that, both by increasing the size of the credit and by making it “fully refundable” to include families without federal tax liabilities.

Specifically, the act would provide families with $300 per month ($3,600 per year) for each child under the age of six, and $250 per month ($3,000 per year) for each child under the age of 17, while slowly phasing out benefits for households with six-figure incomes. With such a system in place, we estimate that the number of children in poverty would decline by 4.5 million — a 40 percent reduction — while “deep” child poverty (defined as 50 percent of the poverty line) would be cut in half. [72]

Child allowances solve for a number of pernicious market failures common in any modern economy. In particular, while an individual typically reaches their peak earnings in their 40s and 50s, fertility peaks in one’s 20s and 30s. This gap means that most families face the extra costs of raising a child at precisely the point in their life cycle when money is tightest. In a competitive market, a childless worker and a single mom with two kids will be paid the same wage for the same job. As result, having a child is itself a risk factor for falling into poverty. [73] A child allowance solves this problem by, in essence, transferring one’s future earning potential to the present in order to supplement household income in proportion to the number of child dependents who cannot generate income of their own.

As the Niskanen Center’s Joshua McCabe has argued, the logic of income supplementation was invoked in most countries with child allowances. In the U.S., in contrast, the CTC was explicitly created according to the logic of “tax relief.” [74] This has made expanding the credit to those without a federal tax liability an uphill battle – and long overdue.

While a child allowance seems novel in the American context, similar policies are commonplace across the industrialized world. Defined as any periodic, per-child cash transfer to households, child allowances have also been endorsed and enacted by governments across the ideological spectrum. Canada’s generous Child Benefit, for example, was originally enacted by a Conservative government as a nonbureaucratic way to support families. Since its expansion in 2016, Canadian families now receive monthly allowances equivalent to roughly $5,000 U.S. dollars per child, per year. [75]

For all the conservative fears of unconditional benefits reducing the incentive to work, studies of Canada’s child benefit show it actually increased total employment. This is because, as a flat benefit, a dollar earned is a dollar kept, unlike in traditional welfare programs in which benefits are abruptly clawed back. [76] Among low-income, unmarried households, for example, parents appear to use the benefit to afford child care and increase their labor force participation. [77] Following its 2016 expansion, the Bank of Canada even reported that the Canada Child Benefit helped move our neighbor to the north closer to full employment. [78]

With few or no conditions on how the money can be used, parents end up making surprising – and surprisingly effective – choices. A study of the Canadian program, for example, found child allowances increase spending on direct inputs like education or pediatric health care, as well as so-called “household stability items.” [79] These include routine bills and other household goods that help to dramatically reduce parental stress and create an overall healthier household. Indeed, the same research found Canadian parents reduced their spending on alcohol and tobacco by six cents on the dollar, presumably because they were less stressed financially. A child allowance thus embodies the motto “leave paternalism to the parents”: Rather than micromanage parental choices, or promote one ideal of how a family should be structured, child allowances empower parents to harness their local knowledge and direct scarce resources to their highest valued use.

Under the status quo, the U.S. federal government spends over $320 billion per year on children — no small amount. And yet its effectiveness is diluted across more than 100 fragmentary programs. While adult social insurance is overwhelmingly in the form of income support or medical reimbursements, federal spending on children is largely in-kind, including subsidized school lunches, diaper vouchers, baby formula, and a lot of administrative overhead. The result is a convoluted, bureaucratic mess bloated by rent-seeking and waste, whether due to industry interests or politicians trying to leave a legacy. Poor parents, in turn, are forced to navigate a complex welfare bureaucracy, while middle-class parents receive a simple tax credit. Enacting a universal child allowance would thus be an opportunity not only to consolidate these wasteful programs, but also to bring low-income families and children into a common system that treats them with equal dignity and respect. [80]

Imagine, for a moment, that Congress decided to partition Old Age Social Security into various targeted programs. Rather than receive a fixed income to supplement their retirement savings, older adults would instead receive vouchers for qualified nursing homes, food delivered through a special nutritional program, and so on and so forth. The AARP and other advocacy groups would surely deride the change as wasteful and needlessly paternalistic. How, they would argue, could legislators and bureaucrats ever administer in-kind programs that adequately account for the enormous diversity of older people’s needs? And yet children are no less heterogeneous, and likely face an even greater diversity of life challenges that our current system doesn’t adequately take into account. The only difference is their relative lack of voice. [81]

Consider any of the various proposals for federally funded universal day care. While each proposal differs in important ways, they share a common vision of greater federal involvement in child care, regulations that impose national quality standards, and federal subsidies to make formal day care centers either free or heavily subsidized. Typically left off the agenda is any support for home- and family-based models that remain the dominant source of child care in the United States – and the one that surveys find most parents prefer. [82]

Seen through the lens of the working parent, the pursuit of higher child care “quality” — be it in the form of stronger licensing requirements or mandatory curriculum standards — is actively counterproductive. [83] In fact, empirical studies suggest roughly half of every dollar subsidizing child care passes through to higher prices. [84] Child care choice and affordability can instead be tackled simultaneously by relaxing regulations on home and formal day care centers and, in urban areas, reducing restrictions on land use that push up the price of real estate. With appropriate cash benefits to parents and a legal framework to expand lower-cost child care options, there is simply no argument for favoring universal day care outside of social engineering.

COVID-19 has only made the case for a child allowance more urgent. Many families have seen their incomes disappear or become more volatile, while the diversity of household circumstances has dramatically increased. Many schools are going remote, meaning fewer kids have access to in-kind benefits like free or reduced-price school lunches. And with day care centers either closed or at reduced capacity, more parents are turning to friends, family, and home-based child care arrangements as a flexible alternative.

With so many families on the edge of survival, what has long festered as a chronic problem now takes on special urgency. The time for action is now.

Fix Health Insurance with Universal Catastrophic Care

Ensuring access to affordable, high-quality health care is a top priority for reformers across the political spectrum, yet there is little agreement over how to proceed. The layoffs induced by COVID-19 have made reform all the more imperative. Assuming a peak unemployment rate of 20 percent, the Urban Institute estimates that 25 to 43 million people will lose or have already lost their employer-sponsored health insurance. [85] While many of these workers will obtain insurance through Medicaid or the individual marketplace, the Urban Institute’s baseline scenario nonetheless forecasts 29 percent of the newly unemployed remaining uninsured — and up to 40 percent in states that haven’t expanded Medicaid.

Elsewhere in this paper, we argue that the ultimate key to making American health care both accessible and affordable lies in dismantling the numerous and interconnected barriers to competition that make prices here much higher than elsewhere in the world. But even with the removal of all those barriers (a very tall order, indeed, given the lobbying muscle of doctors, hospitals, and drug companies), improvements to the nation’s kludgy, wasteful health insurance system are still needed to expand access and improve affordability.

We believe the goal of universal health coverage should, at this point, be beyond the scope of reasonable debate. [86] The $3.6 trillion question is to figure out how to make it work, and in a way that satisfies the goals of the left and the right. On the left, the basic problem with U.S. health care is characterized in terms of a broken payment system. With payers fragmented into multiple public and private insurers, we forgo the efficiencies of scale that would be achieved through a “single payer” system and create coverage gaps that leave many without access to quality care. On the right, meanwhile, the American health care system is seen as falling far short from the “free market” ideal, and only made worse by the patchwork of government interventions. In particular, third-party payers, cost-shifting, and a lack of price transparency are believed to erode the incentive of consumers to shop for reasonably priced services, while supply-side regulations stifle competition, block entry by would-be innovators, and protect the interests of providers.

Single-payer advocates and free-market reformers tend to talk past one another, but as the Niskanen Center’s Ed Dolan has observed, they may have more in common than it first appears. By and large, the right recognizes that, even under the most market-oriented reforms, there would still be a need for some kind of social insurance to assure the very poor and very sick have access to care. And on the left, most would agree that whatever is done about the payment system, there is a need for more transparency, competition, and innovation than the current system seems able to deliver. The two perspectives can therefore be reconciled, at least in theory. But what does that look like in practice?

We support an approach known as Universal Catastrophic Coverage (UCC). [87] As we describe below, UCC would reduce the fragmentation of our existing system, enable a transition away from our employer-based model, and achieve universal coverage in a way that is conducive to consumer choice and supply-side reform. More of a framework than a specific set of reforms, UCC starts by recognizing the core problem any social insurance program exists to address: financially ruinous but uninsurable risks.

For risks to be insurable by commercial providers, they must be unpredictable. Yet in a study by the Kaiser Family Foundation, 53 percent of Americans reported that they, or someone else in their household, had a preexisting condition that would cause a private insurance company to decline their coverage according to the underwriting practices predating the Affordable Care Act (ACA). [88] This includes chronic conditions like diabetes or heart disease as well as genetic predispositions that make seemingly healthy people a ticking time bomb for insurers.

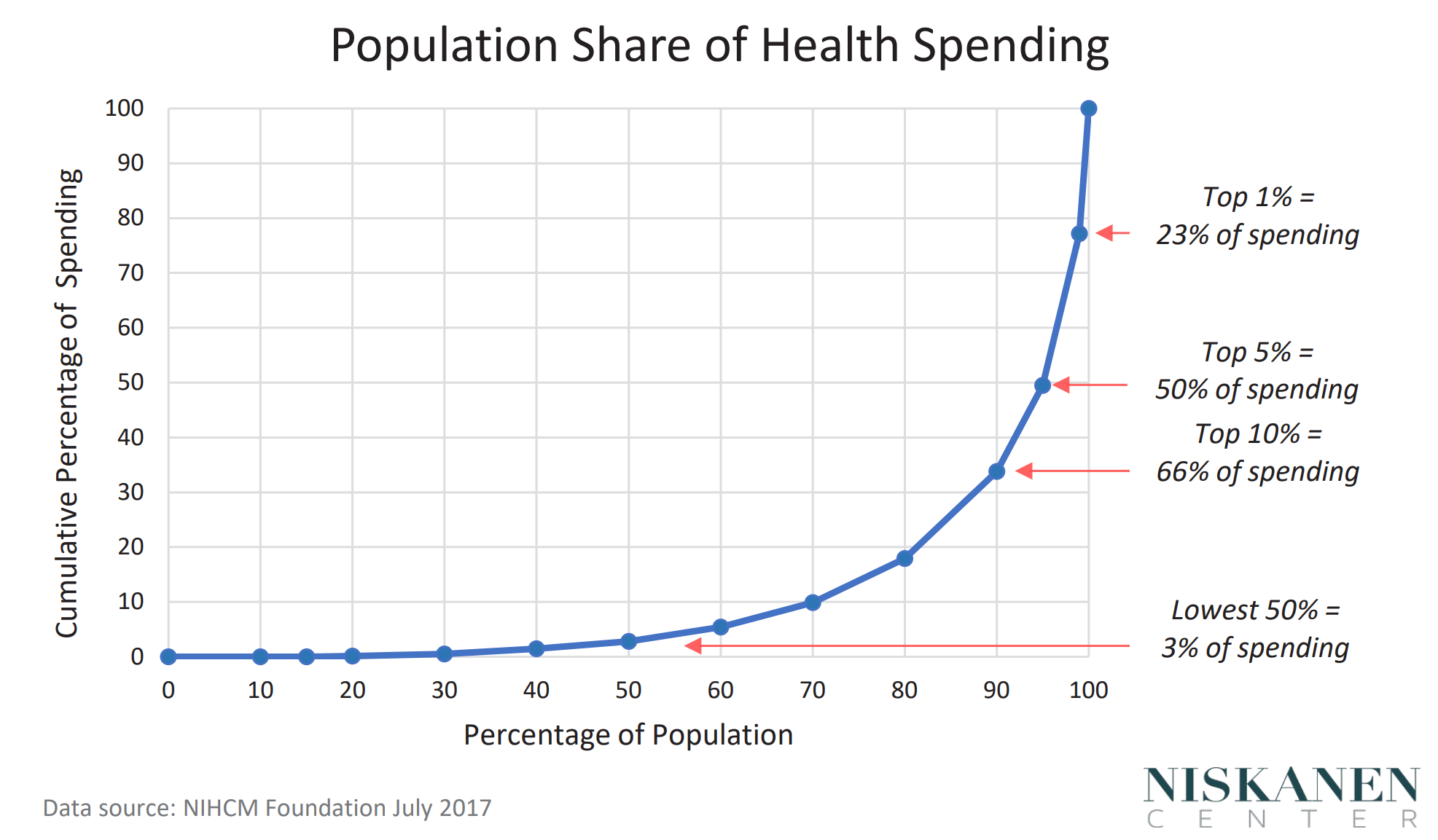

The second standard for commercial insurability is the affordability of an actuarially fair premium, i.e., one high enough to cover the expected value of total claims. In the U.S., however, the healthiest half of the population accounts for just 3 percent of all personal health care expenditure, 5 percent of the population accounts for half of all spending, and just 1 percent for more than a fifth of all spending. Because medical expenses are distributed so unevenly, an actuarially fair premium would exceed the entire income of many people with preexisting conditions.

The ACA attempted to solve the insurability problem through a series of regulations. “Guaranteed issue” and “guaranteed renewal” require private insurers to accept and maintain coverage of all applicants, regardless of their preexisting conditions. “Community rating” goes a step further, by requiring insurers to charge the same premium, based on average claims, to everyone in a general category regardless of their health status. These mechanisms make it possible for people to buy health insurance for a premium that is fixed regardless of their preexisting conditions, but in doing so they rendered the U.S. insurance market vulnerable to adverse selection. Given guaranteed issue, healthy people can avoid paying premiums by simply going uninsured, only to buy into the system when they become ill. As more healthy people dropped out of the market, premiums for those who remained in the pool rose higher and higher, until they became unaffordable. The individual mandate was meant to prevent this problem, but it was likely too weak to be effective with or without the political controversy surrounding it.

Under UCC, by contrast, the insurability problem is addressed head-on by creating a universal tier of coverage for catastrophic health care expenses. The simplest version of UCC needs just two parameters: a low-income threshold for first-dollar coverage, and a deductible that increases as a function of a household’s income.

Deductibles under UCC serve a different function than in conventional “high deductible” insurance plans. [89] While there would be nothing to prevent someone from using the catastrophic tier as their only source of health insurance, they would be required to pay for all of their subcatastrophic expenses out of pocket. In practice, however, the existence of a catastrophic tier would provide a permanent solution to the insurability problem, and thus make supplemental private insurance for expenses within the deductible range far more affordable. Indeed, with a universal backstop for financially ruinous medical expenses, many of the regulations imposed on the private insurance market would become redundant, enabling a broad deregulation of the insurance market and the flourishing of innovative models such as health sharing plans. [90]

More realistic versions of UCC feature additional parameters, including cost-sharing through copays and coinsurance, and exemptions for preventative treatments known to save money in the long run. A full discussion of these and other details are outside the scope of this agenda paper but can be found in Ed Dolan’s white paper on the subject. [91]

For now, it’s worth thinking of UCC as related to high-risk pools or reinsurance, but in a way that makes up for their respective shortcomings. To date, attempts at creating high-risk pools have suffered from underfunding and barriers to enrollment. Identifying who qualifies as high-risk in advance is itself a challenge. A more serious problem for both high-risk pools and reinsurance is the fact that they treat all households equally, regardless of income. As a result, even if such programs succeeded in lowering average premiums, many low- and middle-income consumers would likely find that health coverage remains unaffordable.

UCC addresses both of these problems. Because payments for catastrophic expenses are made retrospectively, UCC would avoid the need to screen for health risks. And because out-of-pocket costs would be scaled to income, UCC would be affordable for everyone. UCC can therefore be thought of as a form of retrospective reinsurance for which the threshold above which private insurers are reimbursed by the federal government (what’s known in reinsurance as the “attachment point”) comes in the form of a deductible, scaled in proportion to household income.

Conservatives may prefer implementing UCC as a form of federal reinsurance for private insurers, while progressives may favor a modified public option that achieves the equivalent outcome. [92] Regardless of how it’s administered, UCC provides the only realistic strategy for reducing the fragmentation of American health care once and for all.

Detailed cost estimates of UCC suggest a baseline version could be implemented in the United States without increasing total spending by households, government, or employers. [93] With a robust cost-saving package, UCC could even stand to reduce consumer outlays on health care and create overall savings for the federal budget. In short, UCC posits a robust role for the government as a provider of social insurance where needed while creating space for market mechanisms where they have the best chance of working.

Endnotes

[1] Derrick Taylor, “ Taco Bell to Test Paying Managers $100,000 a Year ,” The New York Times, January 10 , 2020.

[2] Jeffry Bartash, “ At a 10-year high, wage growth for American workers likely to keep accelerating ,” MarketWatch, March 8, 2019.

[3] Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, “ U.S. Employment and Training Administration, Initial Claims [ICSA] ,” August 31, 2020.

[4] Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, “ Labor Force Participation Rate ,” September 10, 2020.

[5] Eli Rosenberg and Heather Long, “ The U.S. economy added 4.8 million jobs in June, but fierce new headwinds have emerged ,” Washington Post, July 8, 2020

[6] Robert Orr, “ The Great Depression Has Arrived, It’s Just Not Evenly Distributed ,” Niskanen Center, June 12, 2020.

[7] Jose Berrero et al., “ COVID-19 Is Also a Reallocation Shock ,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 27137, May 2020.

[8] Olivia Rockeman and Jill Ward, “ Millions of Job Losses Are at Risk of Becoming Permanent ,” Bloomberg, June 14, 2020.

[9] Jeanna Smialek and Alan Rappeport, “ Federal Reserve predicts years of high unemployment rates and economic uncertainty ,” Chicago Tribune, June 10, 2020.

[10] Samuel Hammond, “ Will Pandemic Jobless Benefits Make Recover Harder? ,” National Review, April 2, 2020.

[11] Also known as the moral hazard, liquidity trade-off. Raj Chetty, “ Moral Hazard versus Liquidity and Optimal Unemployment Insurance ,” Journal of Political Economy, Volume 116, no. 2.

[12] Since misplaced fears that the Fed was too lax after the Great Recession were most pronounced on the free-market right, it is worth quoting Milton Friedman on this point: “Low interest rates are generally a sign that money has been tight, as in Japan; high interest rates, that money has been easy.” Milton Friedman, “ Rx for Japan: Back to the Future ,” Wall Street Journal, December 17, 1997.

[13] Adam Ozimek and Michael Ferlez, “ The Fed’s Mistake ,” Moody’s Analytics, November 20, 2018.

[14] Jared Bernstein, “ The Importance of Strong Labor Demand ,” Brookings Institution, The Hamilton Project, February 2018.

[15] Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, “ Ten-Year Expected Inflation and Real and Inflation Risk Premia, Inflation Expectations ,” August 31, 2020.

[16] Jerome H. Powell, “ New Economic Challenges and the Fed’s Monetary Policy Review ,” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, August 27, 2020.

[17] David Beckworth, “ Facts, Fears, and Functionality of NGDP Level Targeting: A Guide to a Popular Framework for Monetary Policy ,” Mercatus Center, George Mason University, October 1, 2019.

[18] We chose 4 percent for purely illustrative purposes, as the trade-offs from a slightly higher or lower target are trivial compared to the core benefits of a level target. Nevertheless, it is best when a monetary policy regime change does not deviate markedly from historical trends, and in the U.S. case, annual NGDP growth over the last twenty years has averaged around 4-5 percent. The main reason to favor a slightly higher target relates to the secular decline in interest rates. A higher NGDP target (say, 5 percent or 6 percent) would permit inflation to run higher, putting upward pressure on nominal interest rates, and ensuring the federal funds rate avoids the zero lower bound.

[19] Scott Sumner, “ Money and output (The musical chairs model) ,” The Money Illusion, April 6, 2013.

[20] As a stylized example, the “musical chairs” analogy only captures one of the ways inflation targeting distorts long-term contracts relative to a level target. More generally, as Nick Rowe notes, “inflation or price level targeting gives the creditor full insurance against unforeseen changes in future real GDP, and puts all the risk upon the debtor.… NGDP targeting provides a 50-50 aggregate sharing of aggregate risk between creditors and debtors. If real GDP falls 10 percent below what was expected, the price level rises 10 percent above what was expected. The real incomes of both creditors and debtors fall by the same 10 percent.” Nick Rowe, “ Three arguments for NGDP targeting ,” Worthwhile Canadian Initiative, April 28, 2012. The current asymmetric sharing of risk has real-world consequences. For example, since the real value of a fixed nominal mortgage payment declines over time with inflation, households are discouraged from rebalancing their portfolio (i.e. refinancing their mortgage) as frequently as they would otherwise. Joseph Nichols, “ Nominal Mortgage Contracts and the Effects of Inflation on Portfolio Allocation ,” Finance and Economics Discussion Series, Federal Reserve Board, Washington, D.C., March 2007.

[21] Dave Reifschneider et al., “ Aggregate Supply in the United States: Recent Developments and Implications for the Conduct of Monetary Policy ,” International Monetary Fund, November 1, 2013; Laurence Ball, “ The Great Recession’s long-term damage,” Vox EU, July 1, 2014.

[22] J.W. Mason, “ What Recovery? The Case for Continues Expansionary Policy at the Fed ,” Roosevelt Institute, July 25, 2017; Neil Irwin, “ Maybe We’ve Been Thinking About the Productivity Slump All Wrong ,” The New York Times, July 25, 2017.

[23] Bernstein, “ The Importance of Strong Labor Demand .”

[24] In states like Florida, old technology is secondary to prior changes enacted deliberately to make applying for UI difficult. Gary Fineout and Marc Caputo, “ ’It’s a sh—sandwich’: Republicans rage as Florida becomes a nightmare for Trump ,” Politico, April 3, 2020.

[25] As of the July 9 jobs report, states not reporting a single PEUC claim include: Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Kentucky, New Hampshire, Oregon, Virginia, and Wyoming. “ Unemployment Insurance Weekly Claims ,” Seasonally adjusted data, Department of Labor, August 27, 2020.

[26] Kylee Wooten, “ Breaking Down SBA Lending: What is E-Tran? ”, Abrigo, April 1, 2020.

[27] “ SBA Unveils New Lender Gateway to Facilitate PPP Loans ,” ABA Banking Journal, April 7, 2020.

[28] This was due to both the technical failures of PPP, but also the short loan duration and the restrictive use of funds. In particular, eligible non-payroll expenses were capped to only 25 percent of the loan amount, which made the program of limited value to hard-hit industries such as restaurants and food services. Lucas Kwan Peterson, “ The PPP is letting our small restaurants and businesses die ,” Los Angeles Times, April 18, 2020.

[29] Robert Greenstein and Samuel Hammond, “ CBPP & Niskanen Center: Joint Recommendations to Strengthen Senate Republican COVID-19 Economic Response Proposal ,” Niskanen Center, March 23, 2020.

[30] Marc Andreessen, “ It’s Time to Build ,” a16z, April 18, 2020.

[31] Jim Van Erden et al., “ Unemployment Insurance Administrative Funding ,” National Association of State Workforce Agencies, June 2017.

[32] Makena Kelly, “ Unemployment Checks are Being Help Up By a Coding Language Almost Nobody Knows ,” The Verge, April 14, 2020.

[33] Burgess Everett, “ Josh Hawley sets up potential clash in GOP with coronavirus push ,” Politico, April 6, 2020.

[34] Monica Prasad, “ The Trade-Off between Social Insurance and Financialization: Is There a Better Way? ”, Niskanen Center, August 20, 2019.

[35] Monica Prasad, The Land of Too Much: American Abundance and the Paradox of Poverty , (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012).

[36] Fineout and Caputo, “ ’It’s a sh—sandwich .”

[37] Rebecca Dixon, “ Software Update Required: COVID-19 Exposes Need for Federal Investments in Technology ,” Hearing before U.S. House of Representatives, National Employment Law Project, July 15, 2020.

[38] Ibid .

[40] Tom Temin, “ Congressman argues for boosting Technology Modernization Fund by 40x ,” Federal News Network, May 21, 2020.

[41] Tom Temin, “ IRS programming mystery continues ,” Federal News Network, January 7, 2020.

[42] Tom Temin, “ IRS clutches its modernization holy grail ,” Federal News Network, January 2, 2018.

[43] “ Taxpayer First Act – IRS Modernization ,” Internal Revenue Service, August 18, 2020.

[44] Bob Bryan and Joe Perticone, “ The House passed a bill that could bar the IRS from creating a ‘free’ tax-preparation software like TurboTax – here’s what it means for you ,” Business Insider, April 20, 2019.

[45] Justin Elliot, “ Congress Is About to Ban the Government From Offering Free Online Tax Filing. Thank TurboTax ,” ProPublica, April 9, 2019.

[46] As Vox’s Dylan Matthews has noted, “Denmark, Sweden, Estonia, Chile, and Spain already offer ‘pre-populated returns.’ In a number of countries, like Japan and the UK, the vast majority of people don’t have to file tax returns at all, pre-populated or otherwise. Instead, through a system known as ‘precision withholding,’ the government takes exactly the right amount out of every paycheck. If they find that a mistake was made — not accounting for a charitable donation or mortgage interest, for example — they find that mistake in charity and bank records, and they fix it for you.” Dylan Matthews, “ Elizabeth Warren has a great idea for making Tax Day less painful ,” Vox, April 14, 2018.

[47] Drew Desilver, “ As coronavirus spreads, which U.S. workers have paid sick leave – and which don’t? ”, Pew Research Center, March 12, 2020.

[48] Brian Mullahy, “ Utah Sen. Mike Lee defends 'no' vote on coronavirus bill ,” KUTV, March 19, 2020.

[49] Katharine Abraham and Susan Houseman, “ Proposal 12: Encouraging Work Sharing to Reduce Unemployment ,” Brookings Institution, The Hamilton Project, June 19, 2014.

[50] Alison Griswold, “ Europe is turning to an age-old German work scheme to protect jobs from Covid-19 ,” Quartz, April 30, 2020.

[51] “ Work Sharing: An Alternative to Layoffs ,” National Employment Law Project, Center for Law and Social Policy, July 6, 2016.

[52] Jose Barrero et al, “ COVID-19 Is Also a Reallocation Shock ,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 27137, May 2020.

[53] “ Public expenditure and participant stocks on LMP ,” OECD Social Expenditure Statistics (database), 2020.

[54] Council of Economic Advisers, “ Active Labor Market Policies: Theory and Evidence for What Works ,” Issue Brief, December, 2016.

[55] Edward Alden, Failure to Adjust: How Americans Got Left Behind in the Global Economy , (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2016).

[56] “ Employment and Training Programs: Department of Labor Should Assess Efforts to Coordinate Services Across Programs ,” U.S. Government Accountability Office, March 28, 2019.

[57] Samuel Hammond, “ On Workforce Investment ,” American Compass, June 9, 2020.

[58] Illenin Kondo, “ Trade Displacement Multipliers: Theory and Evidence Using the U.S. Trade Adjustment Assistance ,” National Bureau of Economic Research, September 2017.

[59] Bryan Caplan, “ Free Trade Lets Us Turn Corn into Cars ,” Foundation for Economic Education, February 21, 2018.

[60] How each state calculates UI benefits is extraordinary variable and complex, as this Twitter thread highlights: Matt Darling, Twitter post, Jul 25, 2020, 6:41 pm, https://twitter.com/besttrousers/status/1287171101395746816

[61] “ Unemployment Insurance: Consequences of Changes in State Unemployment Compensation Laws ,” Congressional Research Service, October 23, 2019.

[62] David Autor et al., “ The China Shock: Learning from Labor-Market Adjustment to Large Changes in Trade ,” Annual Review of Economics, Vol. 8, pp.205-420, August 8, 2016.

[63] “ Unemployed persons by duration of unemployment ,” Economic News Release, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

[64] “ Nevada’s Reemployment and Eligibility Assessment Program ,” Social Programs That Work, May 27, 2020.

[65] “ Reemployment Services and Eligibility Assessment Grant ,” Employment and Training Administration, U.S. Department of Labor.

[66] “ How States Are Using Reemployment Services and Eligibility Assessments (RESEA) ,” National Association of State Workforce Agencies, March 27, 2019.

[67] Indivar Dutta-Gupta et al., “ Lessons Learned From 40 Years of Subsidized Employment Programs ,” Center on Poverty and Inequality, Georgetown Law School, Spring 2016.

[68] Samuel Hammond, “ The ELEVATE Act Explained: A ‘Job Guarantee’ That Can Actually Work ,” Niskanen Center, January 24, 2019.

[69] Samuel Hammond, “ Reducing Child Poverty Requires Closing the Cash Benefit Gap ,” Niskanen Center, August 4, 2017.

[70] “ Social Expenditure Database (SOCX) ”, OECD.

[71] “ American Family Act ,” Sen. Michael Bennet.

[72] Samuel Hammond and Robert Orr, “ The American Family Act: An Analysis of the Bennet-Brown Child Allowance ,” Expand the Child Tax Credit, Niskanen Center.

[73] Sophia Addy et al., “ Basic Facts About Low-Income Children ,” National Center for Children in Poverty, January 2013.

[74] Joshua McCabe, The Fiscalization of Social Policy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

[75] Sophie Collyer et al., “ What a Child Allowance Like Canada’s Would Do for Child Poverty in America ,” The Century Foundation, July 21, 2020.

[76] Samuel Hammond, “ Bad Arguments Against a Child Allowance ,” Niskanen Center, May 11, 2017.

[77] Tammy Schirle, “ The effect of universal child benefits on labor supply ,” Canadian Journal of Economics, Vol. 48, issue 2, pp. 437-463, 2015 (March 2014 draft).

[78] “ Liberal government to boost Canada child benefit payments ,” CBC News, October 23, 2017.

[79] Kevin Milligan and Mark Stabile, “ Do Child Tax Benefits Affect the Well-Bring of Children? Evidence from Canadian Child Benefit Expansions ,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, Vol. 3, No. 3, pp. 175-205, August 2011.

[80] Samuel Hammond and Robert Orr, “ Toward a Universal Child Benefit ,” Niskanen Center, October 25, 2016.

[81] Samuel Hammond, “ What Libertarians and Conservatives See in a Child Allowance ,” Spotlight on Poverty & Opportunity, May 31, 2017.

[82] Samuel Hammond, “ The False Promise of Universal Child Care ,” Institute for Family Studies, February 28, 2019.

[83] Samuel Hammond, “ Cash is Superior to Child Care ,” Niskanen Center, June 26, 2017.

[84] Luke Rodgers, “ Give credit where? The incidence of child care credits ,” Journal of Urban Economics, Vol. 108, pp. 51-71, November 2018.

[85] Garret B. and Gangopadhyaya A., “ How the COVID-19 Recession Could Affect Health Insurance Coverage ,” Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, May 4, 2020.

[86] Ed Dolan, “ Universal Healthcare Access is Coming. Stop Fighting It and Start Figuring Out How to Make it Work ,” Niskanen Center, March 28, 2017.

[87] Ed Dolan, “ Universal Catastrophic Coverage: Principles for Bipartisan Health Care Reform ,” Niskanen Center, June 25, 2019.

[88] Gary Claxton et. al. “ Pre-existing Conditions and Medical Underwriting in the Individual Insurance Market Prior to the ACA ,” Kaiser Family Foundation, December 12, 2016.

[89] Rajender Agarwal et al., “ High-Deductible Health Plans Reduce Health Care Cost And Utilization, Including Use Of Needed Preventive Services ,” Health Affairs, Vol. 36, No. 10., October 2017.

[90] For an overview of health sharing plans, see John Goodman, “ Alternatives to Obamacare ,” Forbes, January 30, 2019.

[91] Ed Dolan, “ The Role of Prevention in Health Care Reform ,” Niskanen Center, May 4, 2018.

[92] Ed Dolan, “ Medicare for America: A Health Care Plan Worth a Closer Look ,” Niskanen Center, June 13, 2019.

[93] Ed Dolan, “ Could We Afford Universal Catastrophic Health Coverage ?” Niskanen Center, June 5, 2018.

.png)