The Federal Reserve is the nation’s first line of defense against recession. Unlike the Congress, which controls taxes and government spending, the Fed can make changes in interest rates on a moment’s notice — even late on a Sunday afternoon, as it did on March 15.

The Fed’s policy instrument of first resort is its control over short-term interest rates. The specific rate it normally targets is called the federal funds rate — the rate that banks charge to one another for overnight loans of funds held in their reserve accounts at the Fed. The price of borrowing reserves, in turn, strongly influences the rates at which banks are willing to make loans to businesses and consumers.

Despite the Fed’s close oversight, the effective federal funds rate is actually a market rate that varies from day to day according to changes in supply and demand. However, the Fed does not let the rate wander just anywhere. Instead, it sets policy targets in the form of upper and lower limits for the rate, usually a quarter of a percentage point apart. If a surge in demand for reserves threatens to push the effective rate through the upper end of the target range, the Fed supplies new reserves to the banking system by buying short-term securities. If demand weakens and the rate falls, the Fed withdraws reserves to limit the supply and keep the rate from falling through the floor.

This system works well as long as market interest rates are well above zero, which they normally are. Things change, though, when the federal funds rate approaches zero, where it hits an effective lower bound. Given the structure of U.S. financial markets, that lower bound lies somewhere between zero and 0.25 percent. (Central banks in some other countries have been able to push their own target rates a bit below zero.)

Once the federal funds rate hits its effective lower bound, the Fed is out of ammunition, at least as far as conventional monetary policy goes. It can’t then use a lower federal funds rate to stimulate the housing market by pulling down mortgage rates, or to stimulate business investment by pulling down the rate on corporate bonds.

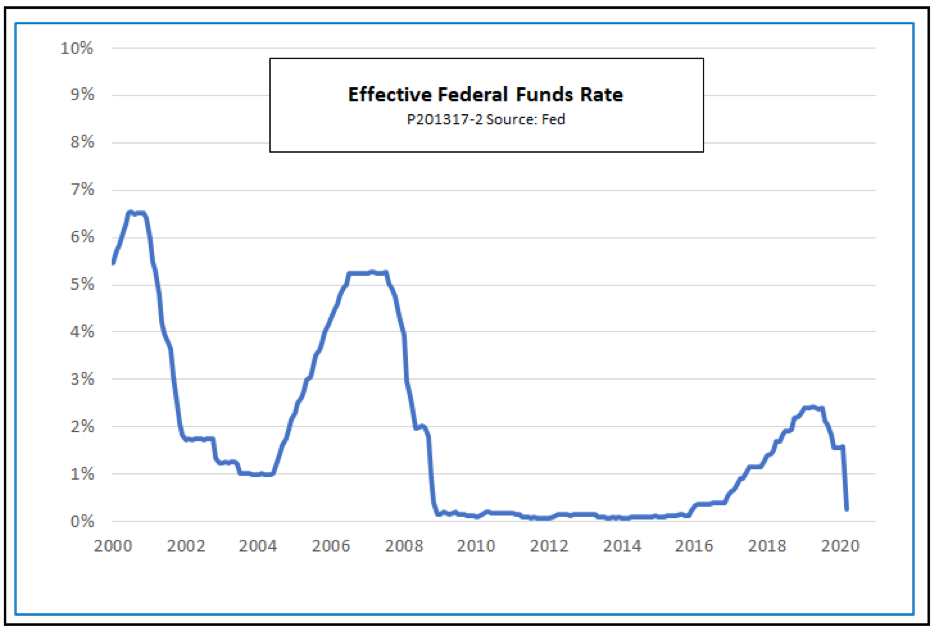

Until 2008, the effective lower bound was just a theoretical construct. Rates never got that low, even during the Great Depression. But since 2008, rates have fallen to the zero bound twice, the second time being just this week:

When the Fed is out of ammunition for its weapon of choice, the federal funds rate, it can still fight on with whatever it has left. The central banking equivalent of throwing a hand grenade is quantitative easing (QE) — a policy of buying longer-term assets to flood financial markets with liquidity. On March 15, at the same time it cut the federal funds target to a range of 0 to 0.25 percent, the Fed announced it would deploy its QE weapon in the form of a $700 billion purchase of long-term Treasury debt and mortgage-backed securities.

So, how is QE actually supposed to work? Economists do not entirely agree.

A pair of closely related theories, called portfolio balance and segmented markets, hold that QE works by flattening the yield curve — a curve that shows how interest rates vary according to the term to maturity of otherwise similar securities. For example, the yield on one-year Treasury securities is normally higher than the yield on one-month Treasuries, and the yield on 10-year Treasuries is normally higher still. Since commercial bonds and mortgages are riskier than Treasuries, the yield on a 10-year corporate bond or 10-year mortgage is higher than that on a 10-year Treasury, but both mortgages and corporate bonds normally follow the same pattern of higher yields for longer terms of otherwise similar instruments.

The idea behind the portfolio balance and segmented market theories begins with the premise that if the Fed buys lots of long-term Treasuries, their prices will go up and their yields will go down. That, in turn, will pull down the yields on long-term mortgages and corporate bonds. Lower bond rates will spur corporate investments and low mortgage rates will encourage home construction. Economic activity as a whole will take off, and all will be well.

It certainly sounds plausible. The problem is, as the next chart shows, the yield curve right now is already unusually flat. In fact, until recently, along part of its range, it was actually “inverted,” which means, in market-talk, that longer-term securities have lower yields than those with shorter terms. For example, as of March 2, 2020, the yield on 10-year Treasuries was just 1.1 percent, compared to 1.41 percent on the one-month maturity. Even 30-year Treasury bonds were yielding just 1.66 percent.

By March 20, the Fed’s actions had brought short term rates down sharply, to just 0.04 percent for 1 month Treasuries and 0.05 percent for 6 months. However, long-term rates had barely budged, falling only to 1.55 percent for the 30-year bond. Although no longer inverted, the low rates at the long end of the curve left little room for the portfolio balance effect to operate.

In contrast, on the eve of the Fed’s first experiment in quantitative easing, in November 2008, the yield curve had a normal, upward-sloping shape. The potential for stimulating the economy by flattening out the curve looked a lot more hopeful then than it does now.

A second widely-held theory is that QE works mainly by signaling. The idea here is that regardless of the effect on rates, the dramatic action of purchasing billions of dollars’ worth of long-term securities will show the market that the Fed is serious about stimulating the economy. Since such a massive purchase will necessarily take a while to reverse, the markets will know the Fed intends to keep up its stimulus for a long time. That, in turn, will give firms and households the confidence to make long-term investments in factories and houses.

But the problem with the signaling theory right now is that markets are already expecting the Fed to maintain an easy monetary policy for years to come. The record low interest rates on long-term bonds and mortgages are themselves one indication of that. Another indication comes from extremely low inflation expectations. In the past, the one thing that could be relied on to trigger monetary tightening by the Fed has been rising inflation. Currently, though, the Cleveland Fed reports a 10-year expected inflation rate of just 1.42 percent. That is well below the Fed’s inflation target of 2 percent, and thus below the lowest inflation rate at which it would be expected to start tightening policy. Back in 2008, the 10-year expected inflation rate was right on the 2 percent mark, implying a greater probability of future tightening, and giving firms and households more urgency to take advantage of low rates while they lasted.

In any event, theory is just theory, right? So why not look at how QE actually worked out the last time it was tried?

Between 2008 and 2014, the Fed undertook three waves of quantitative easing, popularly known as QE1, QE2, and QE3. Their objective was to first put an end to the Great Recession, which had begun in December 2007 and did not reach its low point until June 2009, and then to accelerate a sluggish recovery. Many economists have studied these episodes, using a wide variety of statistical methods. Stephen Williamson of the St. Louis Fed summarizes their conclusions in these terms:

Evaluating the effects of monetary policy is difficult, even in the case of conventional interest rate policy. With unconventional monetary policy, the difficulty is magnified, as the economic theory can be lacking, and there is a small amount of data available for empirical evaluation. With respect to QE, there are good reasons to be skeptical that it works as advertised, and some economists have made a good case that QE is actually detrimental.

Maybe you would prefer to do some armchair analysis yourself instead of taking Williamson’s word for it. If so, the next chart provides at least an inkling of why the econometricians have such a hard time teasing out the effects of the 2008-2014 version of QE.

The chart shows two lines. The blue line shows the scale of the QE efforts, represented here by the path of the monetary base, which is the sum of reserves and currency that the Fed pumped into the financial system through its program of asset purchases. Before QE, the monetary base and nominal GDP tracked fairly closely, as pre-QE textbooks said they should. The remarkable thing is that the massive monetary effects of QE produce barely a ripple in the black GDP line. Of course, it is possible that nominal GDP would have turned dramatically downward without the QE. Still, the chart helps to understand why not everyone has become a believer.

If the points made above regarding today’s flat yield curve and low inflation expectations are correct, then the conditions for QE to stimulate demand are less favorable now than they were in 2008-2014. Furthermore, as I explained in an earlier post, demand stimulation, even if successful, may not be enough this time. The reason is that the recession that is beginning now combines a shock to demand with a shock to supply. Because supply chains are broken and sick workers can’t report to their jobs, many firms would not be able to increase output even if the demand were there.

The bottom line, then, is that we can’t just breathe a sigh of relief and wait for QE to do its magic. There are, to be sure, other important things the Fed can do to help the economy. It can support liquidity if selected financial markets start to freeze up, as it did this week for commercial paper. It can coordinate with the central banks of other countries, easing strains on global currency markets. It could even buy a wider range of assets, including municipal and corporate bonds. But just fattening its balance sheet, as in QE1, QE2, and QE3, will probably not be enough.

The missing element is fiscal policy, which is the responsibility of Congress and the White House, not the Fed. As Fed Chair Jay Powell himself said, in his comments on this week’s actions, “Typically fiscal policy does pay a major role when there are downturns. That will probably need to be the case here as well.”

Watch this space for more on fiscal policy.

Note: An earlier version of this post gave a wrong date for the yield curve chart. The blue series in the chart shows data for March 2, not March 17.