As lawmakers haggle over reforms to preserve the expanded support for families enacted in the 2021 American Rescue Plan, extending the Child Tax Credit for the youngest children should be a top priority.

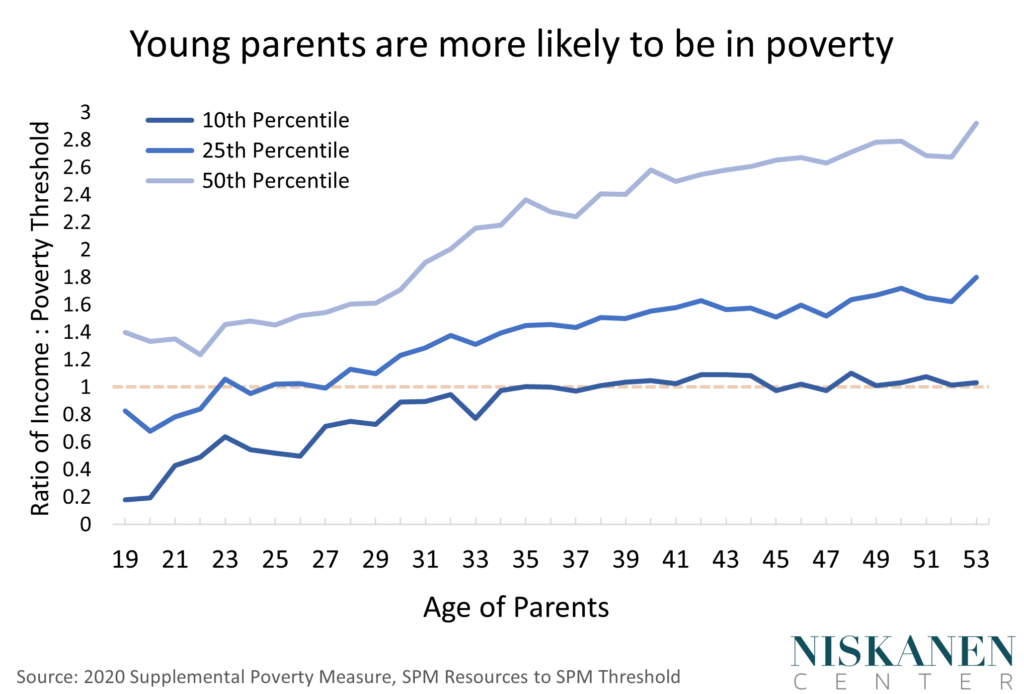

Childhood poverty is concentrated among younger children–largely because younger children tend to have younger parents. Since young parents are earlier in their careers, they experience less stable employment and lower average earnings. Telling would-be parents to simply delay having children until their mid-30s isn’t a desirable option either. The Child Tax Credit (CTC), particularly one that delivers greater benefits to younger children, can alleviate the mismatch between the age when parents maximize their earnings and the age when they have kids, maximizing the CTC’s per-dollar impact on child poverty.

Young kids have young parents — and they earn less

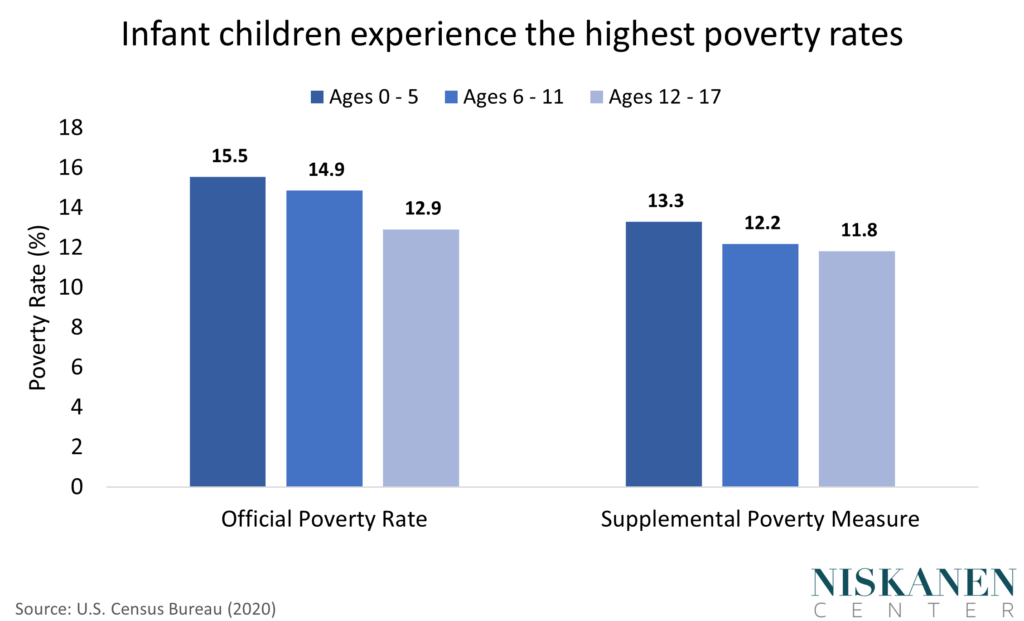

Kids are most likely to experience poverty before they enter the school-age years. In 2019, about 15.5 percent of children ages 0 to 5 were in poverty according to the Official Poverty Measure, compared with 12.9 percent of children between the ages of 12 and 17 — a 20 percent difference. A similar pattern, though less pronounced, can be found in the Supplemental Poverty Measure, which incorporates refundable tax credits such as the Child Tax Credit, among various other differences.

Poverty rates among children tend to decline with age as parents advance through their careers. As of 2019, the average age of a first-time U.S. mother was 27 overall, and 25 for Black and Hispanic mothers. However, the average conceals the educational divide of when women choose to have kids, with some beginning in their early 20s, and others waiting until their 30s. Either way, workers only hit their peak earnings years between 35 and 54. Employment tends to peak at these ages, while workers with more years under their belt experience less overall job precarity.

Young parents with fewer financial resources are less capable of investing in their child’s needs. The stresses associated with financial hardship may also impede child development. As a result, children who grow up in poverty fare worse on various metrics, including educational attainment, physical health, and emotional well-being.

Gender is a significant factor here, too. Women tend to experience a substantial decline in earnings in the years following childbirth. This “motherhood penalty” is primarily due to a reduction in employment, as mothers are likely to spend time caring for newborns in the months or years following birth, with many transitioning into the role of full-time homemakers. This loss of a second paycheck creates an immediate negative income shock. And the disruption to earnings is experienced even more acutely for divorced, widowed, and never-married households. Even a relatively short spell outside the labor force is likely to negatively impact a mother’s earnings.

We all have a stake in strong families

Pushing parents to delay starting a family until they’ve reached peak earnings potential isn’t the answer. The average age of first-birth is already trending upward, with its own pernicious side effects. The trend towards having children at an increasingly advanced age reduces overall fertility. It contributes to the gap between the number of children that women report wanting to have and the number of children they ultimately end up having. What’s more, rates of medical complications during pregnancy increase substantially as women get older: The maternal death rate for women aged 40 and older is six times higher than for those younger than 26.

Finally, declining fertility has wider societal drawbacks. The U.S. population is projected to keep growing over the next four decades, but at a slower pace. That slackening means social programs like Social Security and Medicare that depend on the ratio of workers to retirees will come under strain. Policies to improve the financial standing of parents, particularly younger ones, could help — especially if, like child benefits, they help parents raise their children’s future earnings potential.

A compromise should prioritize the youngest

Few policies deliver as much bang for the buck as the CTC, producing social benefits worth up to eight times the cost. The child credit for young children is particularly important in this regard. Parents of young children tend to be young themselves, earn less in the labor market, and have a higher likelihood of being in poverty. A monthly, fully-refundable CTC for preschool-aged children is thus well structured to maximize the per-dollar impact on child poverty while delivering unconditional resources to parents when they need them most.

With uncertain prospects for extending the expanded CTC in its entirety, a strong case can be made for prioritizing full-refundability for younger children in particular. Not only would doing so deliver a greater poverty impact, but concerns about work incentives would also be lessened given the special and temporary obligations of parents with infant children. While renewing the expanded CTC with full-refundability for all ages remains the first-best policy, if that approach can’t secure sufficient support in Congress, enacting a child allowance for children ages 6 and younger is the next best option.

Photo Credit: iStock