“The Permanent Problem” is an ongoing series of essays about the challenges of capitalist mass affluence as well as the solutions to them. You can access the full collection here, or subscribe to brinklindsey.substack.com to get them straight to your inbox.

“We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.” Peter Thiel’s famous lament captures the disappointment of those of us raised on mid-20th-century technological optimism. Back in the 1960s we were sending men to the moon and exploring the ocean depths, and we thought we were just getting started. Back then, a bright and gleaming future beckoned with moon bases, space stations, underwater cities, limitless energy from fusion power, robots at our beck and call, and yes, flying cars.

The pithiest way to sum up that future that never came: we were expecting “The Jetsons.” The animated sitcom premiered in prime time on September 23, 1962 – I was less than a month old – before moving to Saturday morning syndication the following year. The show follows the Jetson family of Orbit City – George, Jane, Judy, and Elroy, along with Astro the talking dog and Rosey the robot maid – as they mine the comic potential of life in 2062. George brings home the bacon by working three hours a day, three days a week at Spacely Space Sprockets; Jane, a homemaker with a maid and a house full of push-button appliances, volunteers with the Galaxy Women Historical Society when she isn’t out shopping; Judy and Elroy are students at Orbit High and Little Dipper School, respectively. And of course, the family toodles around in a flying car, which conveniently folds up into a briefcase when George reaches the office.

The Jetsons dream died quickly. You could see the culture shifting just three years later, with the debut of another animated classic from the 60s: the Charlie Brown Christmas special, in which Charlie struggles to cope with the rampant commercialization of the season. The Peanuts’ strong consensus is that they need “a great, big, shiny aluminum Christmas tree” for their Christmas play, but Charlie decides to buy a scraggly little natural tree instead. The kids are outraged at first, but it becomes clear that Charlie’s choice better suits the true meaning of Christmas (conveyed by Linus’ recitation of the second chapter of Luke). Before wishing Charlie a Merry Christmas and breaking into “Hark! the Herald Angels Sing” to close the show, the kids conclude, “Charlie Brown is a blockhead, but he did get a nice tree.” Here we see the rejection of the modern association of progress with the displacement of the natural and the triumph of the artificial – an association epitomized by the Jetsons aesthetic of all glass and steel and chrome and plastic and not a green living thing to be seen anywhere.

Soon the nascent green sensibility that Charles Schulz expressed would sweep the nation in the form of the modern environmental movement. Dreams of Orbit City quickly gave way to nightmares of a pollution-poisoned Earth; the old ideal of limitless progress through new and better technology was rejected in favor of self-imposed limits and a romantic embrace of the small-scale and primitive. The anti-Promethean backlash was now under way.

When optimism about the future rebounded in the 90s with the collapse of communism and the advent of the internet, the beckoning future now looked distinctly different. In her late 90s book The Future and Its Enemies, my friend Virginia Postrel captured the change in her opening discussion of the 1999 reopening of Disneyland’s Tomorrowland. “Gone is the impersonal chrome and steel of the old buildings…,” she wrote. “In their place is a kinder, gentler tomorrow where the buildings are decorated in lush jewel tones and the gardens are filled with fruit trees and edible plants. Tomorrowland still has spaceships aplenty – the new Rocket Rods ride is the fastest in the park – but it hasn’t shut out things that grow.”

Recalling my own attitudes at the time, with our new vision of information-age progress we looked back at the Jetsons, not with longing, but with a bemused sense of the unpredictable path of progress. Back in the 90s, we were excited about the new track of technological and social advance we were on; the mid-century technocratic ideal didn’t look like progress abandoned, but just a wrong guess as to the direction that progress would take. Virginia captured this sense of things: “The old modernist ideal was indeed too sterile for most tastes. Real people don’t want to live in generic high-rise apartments and walk their dogs on treadmills, à la The Jetsons. Real people want some connection to the past and to the natural world.”

The explosive growth of the internet gave us once again a heady sense of humanity’s expanding powers, but one altered and ultimately disfigured by the anti-Promethean backlash. The culturally dominant vision of the future that took shape in the 90s came to be known as “cyberpunk”: it contrasted an online world of limitless possibilities – the frictionless, disembodied realm of “cyberspace” – with a physical reality dominated by soulless mega-corporations and ruined by environmental despoliation.

Meanwhile, as the 21st century unfolded, and especially in the wake of the global financial crisis and ensuing Great Recession, enthusiasm about the possibilities of the information age cooled and then curdled into disappointed disillusionment. Growth had slowed to half the pace that it averaged during the 20th century; combine that with the persistence of high income inequality that skewed gains toward top earners, and median household income stagnated for an astonishing 16 years before moving past its 1999 peak. Amidst this “Great Stagnation,” concerns about the return of low productivity growth spilled out into broader pessimism about a slowdown in scientific and technological progress.

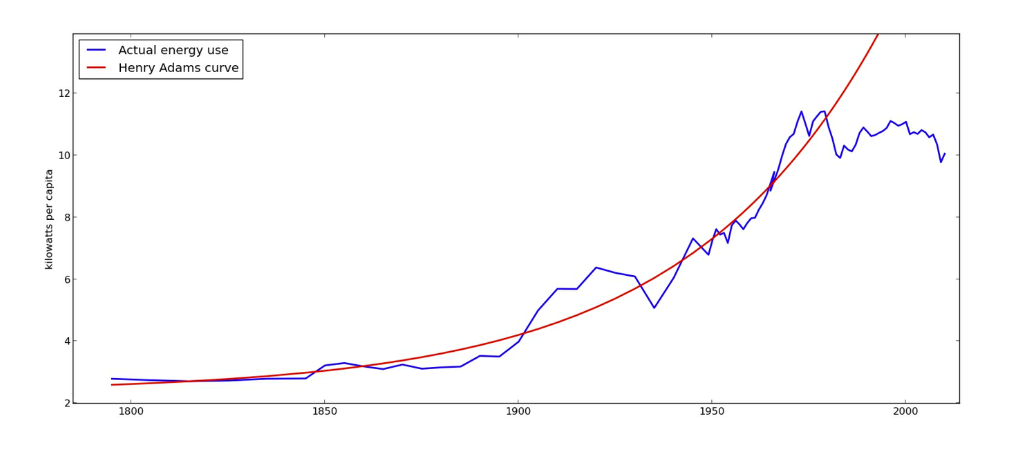

In these changed circumstances, some began to look back at the old mid-century future as an opportunity missed. Peter Thiel made the crack that opens this essay during a 2013 talk at Yale; five years later, J. Storrs Hall self-published the quirky, brilliant Where Is My Flying Car? (subsequently reprinted by Stripe Press). Hall’s chart of the end of the “Henry Adams curve” – the chart shows energy consumption per capita growing exponentially until plateauing in the 1970s and stagnating ever since – captures in one arresting visual the road not taken. The change in perspective has provoked the formulation of a new reform agenda: revitalizing technological progress and economic dynamism after a half-century lull. Prominent voices in this space include Tyler Cowen and Patrick Collison and their call for a new “progress studies,” AEI scholar Jim Pethokoukis and his embrace of “upwing” dynamism and “conservative futurism,” Eli Dourado at the Center for Growth and Opportunity at Utah State, and the newish D.C. think tank the Institute for Progress.

This new current of opinion started out on the right, but has more recently lapped over onto the center-left. In the face of climate change and the need for a rapid transition to clean energy, some progressives have awakened to the huge obstacles posed by earlier progressive policies and entrenched progressive attitudes – namely, the permitting maze that makes building anything on a large scale prohibitively expensive, and the anti-Promethean habits of mind that gradually become indistinguishable from moss-backed conservatism. Here I’m referring to Ezra Klein and his “supply-side progressivism,” Derek Thompson and his “abundance agenda” – by the way, those two have now joined forces to coauthor a new book – and Matt Yglesias and his regular calls for energy abundance.

Jetsons-style technocratic futurism is thus making a comeback. The old obliviousness to environmental harms has been shed, along with visions of progress that left no room for the natural or the historical. Any futurism oriented toward genuine progress must now incorporate a commitment to minimizing environmental harms – but here an “ecomodernist” outlook replaces the anti-Promethean romanticism of old-style environmentalism.

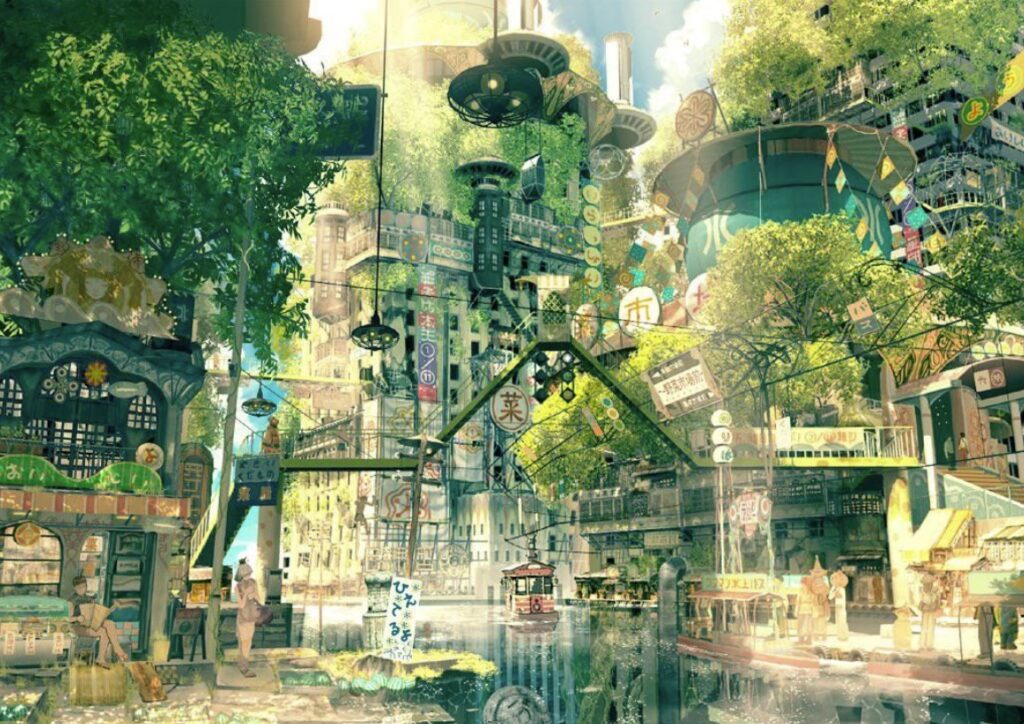

Meanwhile, another species of optimistic futurism has been developing around the same time, this one with roots on the green, anti-technocratic, “small is beautiful” left. Here I’m talking about “solarpunk,” a sci fi genre/aesthetic/social movement. It’s best known through artwork – notably, images of futuristic cities swathed in greenery so that nature and artifice fuse seamlessly.

The name solarpunk seeks to define by contrasting with other sci fi genres: both the dystopian cyberpunk I’ve mentioned already, as well as alternative history “steampunk” (imagining a world in which steam-powered computers carried the Victorian era into the information age). As explained by Adam Flynn, associated with the movement from its early days, “If cyberpunk was ‘here is this future that we see coming and we don’t like it’, and steampunk is ‘here’s yesterday’s future that we wish we had’, then solarpunk might be ‘here’s a future that we can want and we might actually be able to get.’”

Here’s a fuller definition from an online solarpunk reference guide:

Solarpunk is a movement in speculative fiction, art, fashion and activism that seeks to answer and embody the question “what does a sustainable civilization look like, and how can we get there?” The aesthetics of solarpunk merge the practical with the beautiful, the well-designed with the green and wild, the bright and colorful with the earthy and solid. Solarpunk can be utopian, just optimistic, or concerned with the struggles en route to a better world — but never dystopian. As our world roils with calamity, we need solutions, not warnings.

The “solar” part of the name is clear enough: the movement envisions a future built around clean energy, especially solar. But what about “punk” – what’s that supposed to mean? It suggests an oppositional, countercultural stance: egalitarian and anti-hierarchical, frequently anti-capitalist, or at least anti-consumerist throwaway culture. Though the solarpunk idea is still too new and amorphous to have any rigorous ideological framework, it definitely gives off a left-wing vibe. You can see a clear solarpunk sensibility in the works of some prominent left-leaning sci fi writers: just mentioning books I’ve read, I’d include Pacific Edge by Kim Stanley Robinson and Makers and Walkaway by Cory Doctorow. And Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, during a recent live Q&A session on Instagram, spoke out against climate doomerism and called herself a big believer in the optimism of solarpunk.

Unsurprisingly, the hostility to capitalism doesn’t appeal to people on the right, nor does the endorsement of self-proclaimed democratic socialists like AOC. Jim Pethokoukis has written a couple of essays pouring cold water on solarpunk, citing rhetoric like this:

[Solarpunk] imagines a world where energy, usually from the sun or wind, can be used without harming our environment. Where green roofs and windmills allow humans to live in harmony with nature. On the surface it might seem like a rosy, perhaps even naive perspective for our moment, when climate change-fueled disasters are in the news every other day. But imagining Solarpunk purely as a pleasant aesthetic undermines its inherently radical implications. At its core, and despite its appropriation, Solarpunk imagines an end to the global capitalist system that has resulted in the environmental destruction seen today.… Many solarpunks agree that the ‘punk’ element becomes clear when they go past the movement’s visuals and into the nitty gritty. Solarpunk is radical in that it imagines a society where people and the planet are prioritized over the individual and profit.

I’m a big Jim Pethokoukis fan (he has a new book out this week that I’m excited to read – go buy it!), but I think his rejection of solarpunk is overhasty. First of all, under present circumstances – this confusing interregnum of “postindustrial” “postmodernity,” where we can see that the old order is passing and are scrambling to find some new road to a better future – I prefer to look at alternative visions of the future as sympathetically as I can, searching for good ideas to make use of rather than sniffing around for things I disagree with. These days I’m a “lumper,” not a “splitter,” actively seeking ways to combine and synthesize apparently incongruous ideas. You can see this approach in my recent trio of essays where I looked for useful ideas from the post-liberal right, the socialist left, and my old intellectual home of libertarianism.

So let’s look at the core of the solarpunk vision, stripped of the ideological baggage that some people attracted to that vision have brought with them. At the heart of solarpunk is the idea of an environmentally sustainable high-tech future – and that’s the right idea! And it’s the right idea not just because we don’t want to wreck the planet, but because we don’t want to wreck technological dynamism, either. The only way to put the anti-Promethean backlash behind us is to develop technologies that allow humanity and the natural world to prosper together, thereby undermining the indiscriminate cultural hostility to technological progress that currently bogs us down. This is the future that solarpunk envisions. To get to that future, we need as many people as possible to find it attractive enough to work toward, and to fill out those numbers we need people from all ideological starting points.

Beyond this core commitment to clean energy abundance, solarpunk also clearly embraces a countercultural sensibility – an opposition to business-as-usual consumerism. And this is the right idea, too! But both solarpunk proponents who embrace it as a new species of anti-capitalism, and supporters of technocratic capitalist innovation who reject solarpunk for the same reason, are misunderstanding what is the optimal relationship between solarpunk and capitalism: not either-or, but both-and.

To rise to the challenge of the permanent problem and build societies with widespread opportunities to “live wisely and agreeably and well,” we need both the Jetsons and solarpunk. That is, we need large-scale technocratic capitalism and decentralized high-tech communities committed to greater self-sufficiency at the local level. To make our civilization environmentally sustainable, we need to keep advancing the technological frontier until our energy and food systems no longer pose a threat to the rest of the natural world. That can only happen through large-scale capitalism – that is, the combination of entrepreneurial private enterprise and a government that actively promotes ongoing development through big investments in R&D and other market-enabling public gods.

And to make our civilization sociologically sustainable, we need to recognize that mass mobilization into wage employment and consumerist lifestyles is failing to provide most people, especially those outside the professional-managerial elite, with good opportunities for rewarding, fulfilling lives. This is why I’ve come to support the somewhat radical idea of an economic independence movement: to provide an alternative pathway for flourishing by encouraging the creation of vibrant face-to-face communities that are increasingly capable of providing for themselves.

I see a great deal of overlap between the solarpunk vision and my own ideas about economic independence. In particular, for an economic movement to really take off, it will need to be animated by a solarpunk-style countercultural sensibility. I’ve written already about the need for a counterculture – not warmed-over free love and drugs from the 60s, but a producerist, DIY mentality committed to a high degree of local self-sufficiency. The implicit message of consumerism is: specialize very narrowly in market work and outsource everything else to the system, which through the market or the state can take care of all your needs better than you can do for yourself. But while the social technology of specialization and market-mediated exchange is the greatest engine for social progress ever devised, once mass material plenty was achieved it began to experience sharply diminishing returns. For while consumerism promises ever-greater comfort and convenience and ever-more-absorbing entertainment, that road does not lead ultimately to widespread flourishing. Rather, it leads to the dystopia of WALL-E: the progressive atrophying of human capabilities and the regression of the human experience to a blob-like existence of passivity and self-absorption.

Human flourishing does not consist of having somebody else do everything for you: that is the status of helpless infancy and enfeebled old age. Flourishing requires the cultivation and practice of active virtues; it consists of the effortful development and exercise of capacities to act in the world in a way that is useful to others.

Consumerism doesn’t explicitly oppose effortful flourishing, of course. On the contrary, it promises to take all life’s drudgery off your hands so you can concentrate on what really matters. Alas, though, its implicit logic makes it all too easy to never get around to focusing on that what-really-matters stuff. Instead, we tend to fritter away all of the hours gained by commercialized time-saving conveniences on commercialized time-consuming distractions.

We struggle against this logic whenever we take steps to ensure a better “work-life balance”; we do that because we recognize that economic success and a well-lived life are not the same. The problem is that we are supposed to find and maintain this balance individually in the context of a collective way of life that is itself badly out of balance – one that generates strong pressures to elevate economic gain and material comfort over our vital social needs for connection and belonging.

Accordingly, I believe that getting off the greased slide toward WALL-E-fication will require an explicit cultural turn: a movement motivated by a studied rejection of consumerism and hyper-specialization in favor of DIY practical competence and problem-solving ability. From my perspective as an intellectual writing about these things hypothetically, I can see how this counterculture would ultimately supplement and strengthen capitalism; I see how the Jetsons and solarpunk can be synthesized into a large whole that would contain the best of both worlds. But I imagine that for such a countercultural movement to get off the ground, its participants would likely need to take a more partisan view: condemning the corruption and spiritual emptiness of consumerism, denouncing the wastefulness of throwaway culture, hostile to brands and elaborate packaging, preaching temperance in the face of the media experience machine’s many temptations, committed to childrearing and seeing the spread of sub-replacement fertility as definitive proof of the current system’s bankruptcy.

A successful economic independence movement would require people to first resist and then break away from consumerism’s immense gravitational pull – to purposefully set themselves apart from the now-universal system and work to build a life outside it. How do you amass the cultural resources that would empower a movement to take such a stand and make a go of it? Surely it would be easier to accomplish something so extraordinary, so counter to the way of the world, if propelled by extraordinarily powerful motivations – namely, if you believe that the system you’re breaking away from isn’t just incomplete, but morally tainted and even wicked.

So when I read a passage like this one from a solarpunk proponent, I’m not put off by the stridency and the anti-capitalist flavor. On the contrary, I suspect that this is the kind of motivational head of steam you need to make a mass movement possible in this refractory world:

The overarching narrative common to Solarpunk is one of transition from an old, decrepit, pathological Industrial Age to a new sustainable one, which can often incur struggle and conflict based on the passive resistance to change in an ignorant and heavily propagandized society and the active, often violent, resistance of the vested interests benefiting from old power structures and economic hegemonies….

Simply, if crudely, described the Solarpunk culture aspires to the ideal of the Star Trek Economy, but without the contrivance of magical technology. Rather, it is realized through a culture of fundamentally greater reason and responsibility. Solarpunk futurism anticipates and aspires to a sustainable (sometimes imagined as moneyless and stateless) post-scarcity culture on the premise that scarcity, given the technology of the present, is largely a deliberate construct of market economies intended to engineer dependencies and hegemonies concentrating wealth and power. It imagines these overcome largely through the cultivation of local resilience, with renewables in their many forms, independent production, and regional and global resource commons key tools to this end….

Much as Cyberpunk’s archetype was the ‘hacker-hero’ in conflict with corporate and government oppressors, the Solarpunk archetype is a ‘maker-hero’; an eco-tech MacGuyver on a mission of cultural evangelism whose seditious independent technical, industrial, and science knowledge are leveraged on the transformation of the urban/industrial detritus, saving people from the crisis of climate change impacts (represented as “global warming”) and the ravages of late-stage capitalism. Alternatively, their mission may be more focused on the defence of nature; endangered wilderness or species.

This isn’t the tone I adopt: I’m not a fan of the expression “late-stage capitalism,” and I don’t see a moneyless, stateless society in the cards. Meanwhile, you see here the assumption, common in the solarpunk literature, that climate change will cause serious disruptions and breakdowns before the clean energy transition is complete. This assumption underlies the most common narrative about how the solarpunk future arises: as a bottom-up response adapting to the exigencies of ecological crisis and partial social collapse. Sure that makes for good, dramatic sci fi, and the possibility of such dire scenarios can’t be dismissed, but they’re not an inevitability. I sincerely hope that we can arrive at a better future without an intervening catastrophe, and I don’t believe that hope is forlorn.

But I don’t think these differences matter much. What matters is the substantive vision of the future, and the confident sense that it’s not just practically but morally superior to the status quo. That substantive vision – of technological progress that harmonizes human wellbeing with the wellbeing of the rest of the living world, and that allows a high degree of self-sufficiency at the local level – is one that supplies a crucial part of the answer to the permanent problem. (For those interested, the author of the passage I quoted above, Eric Hunting, has written a fascinating deep dive on how solarpunk society might evolve over time that I recommend checking out.)

It’s not the complete answer, though. We still need large-scale capitalism pursuing Jetsons-style progress: breakthroughs in geothermal, small modular nuclear, and fusion; translating those breakthroughs into conversion to indoor farming and cultivated meat; heading out into space to establish a permanent human presence and outsource mining to the asteroid belt; and pushing ahead with the AI revolution that will help make all of these other wonders possible.

The Jetsons future and the solarpunk future aren’t antagonists. There’s room for both, and there’s a need for both. The challenge ahead is managing their co-development and coexistence.