On November 2, Senator Bill Cassidy (R-LA) introduced the Foreign Pollution Fee Act, with Senator Lindsey Graham (R-SC) as co-sponsor. Touted as a “Republican climate policy” by Senator Cassidy, the legislation proposes tiered carbon tariffs at unspecified rates on certain imported goods considered more carbon-intensive than domestically produced goods in the U.S.

The 92-page climate legislation is seeking to use tariffs to also achieve other ambitious goals, such as countering China economically and geopolitically. According to Senator Cassidy’s press release, the bill “is an American plan to address the nexus between energy, economic development, supply chains, national security, and the environment at the expense of China and Russia.”

The Foreign Pollution Fee is problematic in that it could be perceived by U.S. trading partners as a geopolitical policy disguised as a climate policy. Especially perplexing is that the proposal does not include a domestic carbon tax to incentivize domestic producers to reduce their emissions. Rather, the bill features strong language prohibiting any potential interpretation that would allow a domestic carbon price to be enacted.

How does the foreign pollution fee work?

The Foreign Pollution Fee Act proposes carbon tariffs on a list of imported products. The bill provides an extensive list of waiver exceptions and avenues for other countries to get their exports exempted from the carbon tariffs. The “Foreign Pollution Fee” works by:

- Levying tariffs on covered imported products through a multi-tiered tariff framework (though no tariff rates are specified).

- Targeting a list of covered products that are almost identical to the list specified in the Prove It Act, which was introduced in June 2023, commissioning a study on carbon emissions.

- Providing a long list of exceptions under which the carbon tariffs could be waived.

- Proposing an “International Partnership Agreement” through which a country could enter to get some or all the covered products exempted from the carbon tariff.

A multi-tiered carbon tariff framework

The bill proposes an ad valorem tax on imported goods, meaning that the tariff is proportional to the value of the imported goods. The formula that calculates the total tariff amount for a covered imported product is:

Import fee of a covered imported product = The total amount of the product (expressed in dollar values) × A variable percentage number

For example, an importer in the U.S. who imports $200 of a covered product that has a 5% tariff rate would have to pay a carbon tariff of $10.

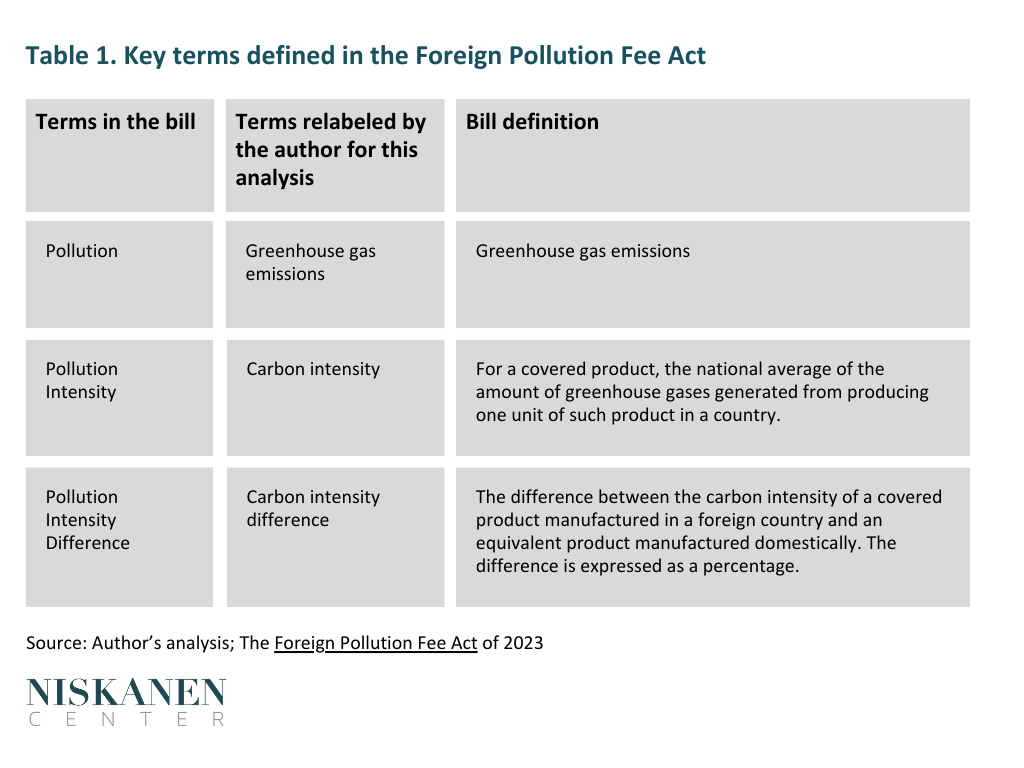

Rather than specifying tariff rates, the bill includes a framework for the U.S. Treasury to structure rates in a multi-tiered system based on the carbon intensity difference between imported and equivalent domestic products. Several terms defined in Senator Cassidy’s bill are key to understanding the multi-tiered tariff framework. As shown in Table 1, although the bill refers to the fee as a pollution fee, it does not address air pollution particulates. The “pollution fee” only targets greenhouse gases.

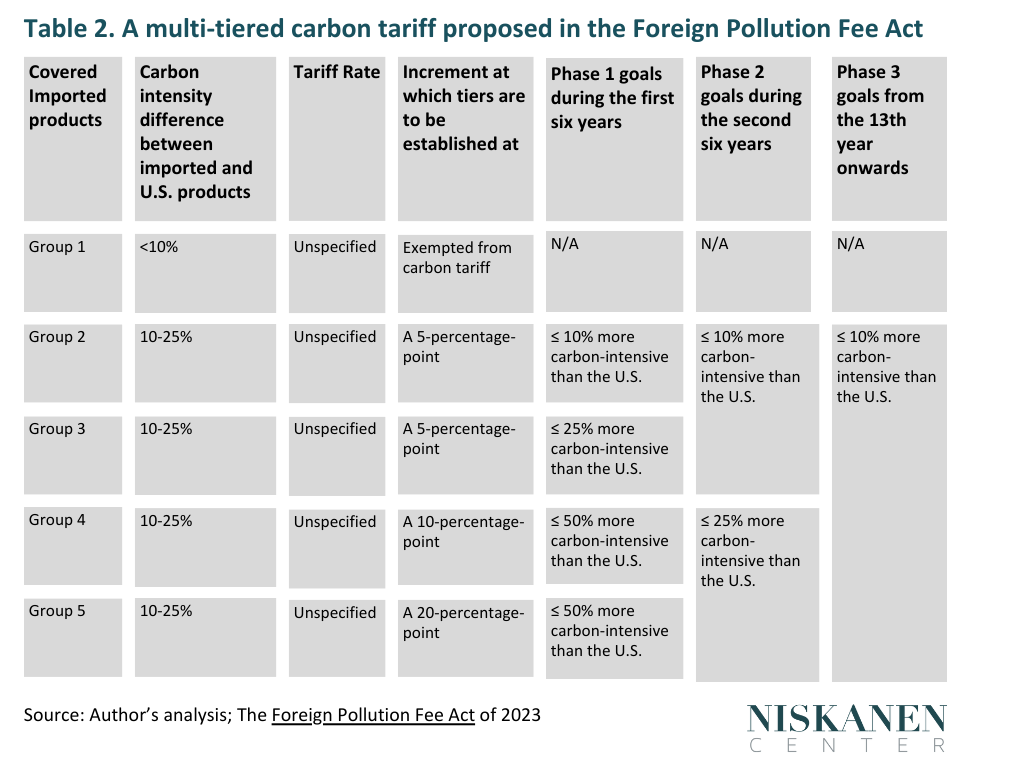

As shown in Table 2, the bill sets up a multi-tiered carbon tariff framework for imported covered products across different ranges of carbon intensity. Imported products that are less than 10% more carbon-intensive than equivalent U.S. domestic products would be exempted from the carbon tariffs.

The bill sets out goals so that imports of any covered product are:

- No more than 50% more carbon-intensive than the U.S. in the first six years

- No more than 25% more carbon-intensive than the U.S. in the second six years

- No more than 10% more carbon-intensive than the U.S. from the 13th year onwards

Covered products

The Foreign Pollution Fee Act includes a list of covered products that would be subject to the carbon tariffs, including primary goods, fossil fuels, critical minerals, and finished products.

As shown in Table 2, the list of covered products in the Foreign Pollution Fee Act is almost identical to the one under the Prove It Act, introduced earlier this year. The bipartisan bill, introduced by Senators Chris Coons (D-Del.) and Kevin Cramer (R-N.D.) (and co-sponsored by other Senators including Senators Cassidy and Graham), requested the Department of Energy to conduct a two-year study of product-level emissions for certain products across the U.S. and other major economies.

Fertilizer is the only outlier in the two almost identical lists of covered products–it’s a covered product in the Prove It Act but not in the Foreign Pollution Fee Act (although ammonia, fertilizer’s main ingredient, is covered in the latter).

Exceptions to waive carbon tariff

The bill includes a long list of exceptions under which the carbon tariffs could be waived, including:

- There is “insufficient domestic production” in the U.S. Specifically, the bill defines “sufficient domestic production” as the U.S. domestic production of a covered product is higher than 5% of the domestic consumption of such a product. In some cases, the percentage number could be lower for purposes including national security, addressing antidumping from a foreign country, and supporting a domestic industry.

- The covered product is imported for national security purposes, like fulfilling a contract with the Department of Defense.

- The imported product originated from a country with a free trade agreement with the U.S., and the carbon intensity is within 50% of the U.S. baseline.

International Partnership

Besides the extensive list of exceptions that would waive the carbon tariffs, the bill also includes a section of “International Partnership Agreements” for other countries to get their exported covered products exempted from the carbon tariffs.

The “International Partnership Agreement” can be structured bilaterally, multilaterally, or part of a broader international forum such as the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) for one, several, or all the covered products.

These are the requirements for a country that wants to enter the “International Partnership Agreement” with the U.S.:

- Use carbon tariffs or equivalent trade policies to incentivize imports of less carbon-intensive products.

- Maintain the ability to determine what policies to adopt for decarbonization domestically.

- Waive any carbon tariffs on imported products from the member countries in the partnership that have a carbon intensity within 50% from the U.S. baseline.

- Waive all other existing tariffs or trade barriers on the covered products.

- Collaborate with the U.S. in carbon intensity monitoring, reporting, and verification.

A nonmarket economy country classified by the World Bank as an upper middle-income or a high-income economy is not eligible to enter the “International Partnership Agreement.”

Potential Challenges to the Foreign Pollution Act

There are significant challenges to the Foreign Pollution Act that would impact its effectiveness in achieving its climate goals.

First, its premise—that the U.S. is a global leader in low-carbon manufacturing and energy production, so we must impose punitive tariffs on more carbon-intensive imports—is flawed. Recent Niskanen research demonstrates that the U.S. falls in the middle of the pack globally in carbon intensity. Specifically, the U.S. is much less carbon-intensive across manufacturing and fossil fuel industries than India, Russia, and China, but it lags behind the U.K., the EU, and Japan. Relying on an incomplete picture of the U.S.’s low-carbon performance compared to other countries would misinform the design of the policy.

Second, it’s puzzling that the bill does not include a domestic carbon tax, even though it proposes levying a carbon price on certain imports. A domestic carbon tax would be critical in incentivizing domestic emissions reduction. The bill explicitly discourages increasing domestic production costs by stating that the carbon tariffs should be implemented “while minimizing any potential increase in domestic costs.” Furthermore, the bill features language that would prohibit any interpretation of the legislation enabling a carbon pricing policy: “Nothing in this Act, or any amendments made by this Act, shall be construed to authorize the creation of any carbon tax, fee, pricing, or other mechanism that imposes additional costs to any covered product … …. which is produced domestically and sold, used, further refined, or distributed within United States or exported to another country for sale or use.”

Third, the Foreign Pollution Act could violate the World Trade Organization (WTO)’s non-discriminatory rules, as a stand-alone carbon tariff proposed in the bill would treat U.S. domestic producers favorably over foreign producers. It would be difficult to use the environmental exception clause in the WTO rules to justify this discriminatory policy design. Because the bill includes many exceptions to waiving carbon tariffs–including those for national security purposes–it would be difficult to convincingly argue that the discriminatory policy design is solely for environmental purposes.

Fourth, the carbon tariff bill could lead to trade tensions with the U.S.’s trading partners. Other countries could perceive the bill as a protectionist policy disguised as a climate policy and retaliate by imposing tit-for-tat tariffs on U.S. exports. Tariffs would negatively impact the economy by raising prices of imported goods, reducing economic output, and lowering employment in affected industries.

The Foreign Pollution Act could also be perceived as a geopolitical policy to counter China. India is more carbon-intensive than China in manufacturing and energy industries, yet only China is mentioned in the legislation’s press release. Indeed, Senator Cassidy recently authored an op-ed discussing carbon tariffs as a policy that would “confront China peacefully but firmly.” Senator Cassidy’s office states that the Foreign Pollution Fee “penalizes foreign countries, namely China, who willfully ignore environmental standards and international norms to undercut manufacturing.” How the bill’s waiver exceptions and the “International Partnership Agreement ” section are written renders it relatively easy for most countries, other than China, to get at least some of their covered exported products exempted.

Finally, even if the bill becomes law, it will have minimal impact on other countries’ emissions for two reasons. First, the legislation provides extensive exceptions and partnership opportunities for other countries to get their exports exempted from the carbon tariffs. Second, China only exports a small portion of its domestic emissions for foreign consumption. For example, in 2018, the emissions embedded in China’s total exports only accounted for 17% of the country’s total domestic emissions. The U.S.’s total imports from China only accounted for four percent of China’s emissions. Using punitive tariffs to coerce China to cut its emissions will likely be ineffective.

Some policy design elements could be helpful for future carbon border adjustment legislation

The Foreign Pollution Act includes some design elements that could be helpful references for future border-adjusted carbon tax legislation. Carbon border adjustments work by levying taxes on imported goods and providing rebates for exported goods. They are implemented along with a domestic carbon tax to tax domestic consumption based on carbon content. Product-level emissions measuring and reporting are critical for implementing carbon border adjustments.

Some of the bill’s policy design elements could be helpful when lawmakers look to design carbon border adjustments under a carbon tax in the future. For example, it has detailed guidance on emissions data measuring, reporting, and verification. It also includes a section on “Facility-specific agreements relating to pollution fees” to allow a facility in a foreign country to be treated at a carbon intensity different from the country’s national average. This would encourage foreign producers to reduce their emissions if they would like to pay less carbon tariffs than the country’s national average. The legislation also defines potential circumvention practices used by a foreign country and proposes corresponding measures that could address the issue.

Conclusion

It’s encouraging that Republican lawmakers are working on addressing climate change through legislative action. However, the Foreign Pollution Fee Act, promoted as a climate policy, does not include a critical component that would incentivize domestic emissions reduction: an economy-wide carbon tax. Without a domestic carbon price, U.S. domestic producers will not be incentivized to reduce their emissions quickly and efficiently.

The bill proposes carbon tariffs at unspecified rates on certain imported goods. It also provides a long list of waiver exceptions for the U.S.’s allies to get exempted from the tariffs. This will likely be perceived as a geopolitical policy disguised as a climate policy.

If addressing climate change is a top priority, lawmakers should focus on enacting effective domestic climate policies, such as a border-adjusted carbon tax, rather than targeted tariffs deliberately designed to counter certain countries.