Last Friday, the departments of Homeland Security (DHS) and Health and Human Services (HHS) officially published a proposed regulation altering the way immigration authorities detain families and children who enter the United States without legal status—like asylum seekers. By nullifying and replacing the Flores Settlement, the administration can accomplish two goals: legally detaining families together indefinitely and relaxing the standards for the places they are detained, even for unaccompanied children.

Since the late 1990s, the way we treat minors, unaccompanied children, and families at the border has been governed largely by a court agreement known as the Flores Settlement Agreement (FSA) and number of conforming regulations. At the time of the enactment of the FSA, the now-defunct Immigration and Naturalization Service handled all individuals encountered at the border.

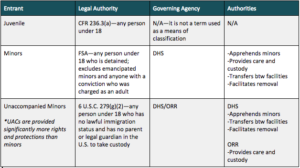

Now, DHS, HHS, and the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) all share responsibility for entrants, depending on factors like age, legal status, and whether they are alone or traveling with parents or guardians. Rules governing the agencies come from a variety of sources in addition to the FSA, including the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) and the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA). Complicating matters, the Homeland Security Act of 2002 (HSA) and William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008 (TVPRA) also include provisions regarding the way we treat children and families encountered at the border.

At a high level, the breakdown of current responsibilities based on individual is depicted below:

The Flores Settlement agreement was used primarily to protect children who arrived at the border without their parents, but was expanded to include children who arrived with their parents in 2015, thus imposing strict detention, care, and release parameters on the government to ensure minors are not detained for more than 20 days.

The Trump administration’s grumbling response to the relatively high standards imposed by FSA and subsequent anti-trafficking and national security laws intended to protect children and families encountered at the border was to institute a “zero tolerance” policy meant to scare away potential asylum applicants by manipulating the laws to separate parents from their children.

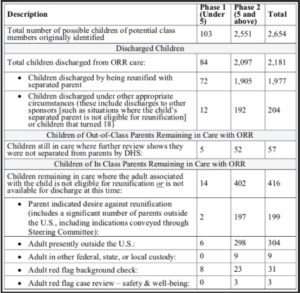

The response was weeks of public outrage over the policy of separating children from their parents at the border and a lack of evidence supporting the administration’s claims that there is rampant asylum fraud. Despite ongoing lawsuits, there are still children younger than 5 years of age who are in custody as of September 6, 2018 according to the joint status report filed in court:

According to the text of the proposed rule, the purpose of the 200+ pages of changes is to terminate the FSA, but also preserve its guiding principle that the “Government treats, and shall continue to treat, all juveniles in its custody with dignity, respect, and special concern for the particular vulnerability.” But given the administration’s shameful track record when it comes to dealing humanely with children and families seeking asylum in the United States, many immigrant advocates are looking to the rule with suspicion, and rightfully so.

The proposed rule quite clearly lays out the administration’s ongoing effort to break down FSA protections and relax all oversight standards in two overarching ways:

1. Keeping more children detained longer and reducing the number of children who benefit from extra protections by virtue of status as an “unaccompanied minor

The proposed rule allows an immigration officer to classify a child encountered at the border as either a minor or an unaccompanied minor (UAC). The distinction is an important one—the proposed rule allows the indefinite detention of minors. Families waiting for a court date for a final decision on a positive credible fear determination can wait years.

UACs are generally afforded significantly more rights than a minor, like the ability to leave government custody to live with a relative. The proposed rule limits who a UAC can be placed with by removing the reference to relative, brother, sister, aunt, uncle, and grandparent, and replaces it with parent or legal guardian. Under the auspices of protecting children from potential tracking, the effect of the change will undoubtedly be the extended detention of UACs.

Further, by cutting off status as a UAC once a child reaches the age of 18—as the new rule proposes doing—their legal status becomes extremely tenuous. It is unknown whether an 18-year-old UAC can remain with their sponsor or whether they have to go to a detention facility while they wait for a court date for their asylum claim.

For minors encountered with their parents, the proposed rule removes the authority of an accompanying parent or legal guardian to swear out an affidavit designating a person to take custody of the child while the parents remain in detention, meaning that child must remain with them in detention, as opposed to living in the United States with a grandparent or uncle.

By expanding the definition of “emergency” circumstances and when the government is experiencing an “influx” of individuals at the border allows the government to bypass safety standards and potentially the basic needs of children and adults. Given that we have been at “influx” levels for years—and the rule does not propose changing the level—excuses for more lax safety standards will become commonplace.

Finally, by unraveling the rights of minors and UACs in the FSA, the government proposes giving all juveniles a telephone call and literature about their legal rights, but no provisions are made for exceptionally young children who cannot read or write or those who don’t speak English.

2. Weakening standards for detention facilities

Currently, the FSA governs conditions of facilities where children are detained, and requires licensure from an appropriate state agency. The proposed rule suggests that the licensure requirements are too arduous on the state level, and contends that federal licensure should be adequate to provide “materially identical assurances about the conditions of the facility, and thus to implement the underlying purpose of the FSA’s licensing requirement.”

The proposed rule does not lay out the conditions that it would deem satisfactory for federal licensure as a family detention facility, but does propose the requirement on DHS to hire an auditor to ensure compliance with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention standards. Of course, there has been significant concern in the past about the conditions of ICE detention facilities, including allegations of physical and sexual assault, a lack of food and water, freezing and hot temperatures, and a lack of medical care.

The FSA also specifies that children are kept in non-secure facilities, and although the agreement does not define the term, it is meant to allow children to roam relatively freely and play outside. The proposed rule suggests defining “non-secure” by defining what a secure facility isn’t. Provided the facility does not provide a 24-hour living setting that prohibits “delinquent” children from voluntary egress in the building through internal or exterior locks or from the premise through secure, perimeter fencing, it is non-secure. The definition effectively allows the government significant latitude in type of facility they can legally detain children—who have committed no crime— within.

When detained together, as a family unit, children may also be subjected to secure facilities—like jails—if they are “unacceptably disruptive,” are an “escape risk,” or for nonviolent offenses like vandalism or intimidating others. For the purposes of clarity, DHS proposes not defining the list of offenses that might subject a child and their family to be detained in a secure facility. The new rule would also allow a child to remain in a secure facility if an alternative was not “available or appropriate,” leaving open a number of questions about oversight and enforcement of standards.

It seems that the administration is looking for a way to authorize the secure detention of minors. In addition to those listed above, the proposed rule also allows for the secure detention of UACs if ORR determines that while in the presence of an immigration officer, a child commits a chargeable offense. Given the administration’s zero tolerance policy, this could include crossing the border, even to seek asylum, or being unlawfully present in the United States.

Finally, the administration proposes significantly more lax standards regarding the transfer of minors from one facility or another, which can take many long hours, including suggesting that whenever “operationally feasible” the government will “make every attempt” to “transport and hold UACs separately from unrelated adults.” In fact, the rule allows DHS to house a UAC with an unrelated adult for more than 24 hours in emergencies.

Up Next

The most important thing missing from this rule are adequate protections for children. Not only does the rule not add protections, it takes away administrative processes meant to protect children—like the right to a bond hearing. When children as young as 2 years of age must represent themselves in court, it is critical that we ensure that they have more adequate protections until we can provide each of them counsel. We need significant oversight of processes and monitoring standards that are currently inadequate, and will be even further degraded by this rule.

It’s important to remember that this is a proposed rule, so the public has 60 days—until November 6, 2018—to offer official comments asserting alternative facts or presenting information about specific aspects of the rule that the government must consider and address prior to the final rulemaking process.

In the meantime, we can also expect challenges to an unsympathetic court over the administration’s compliance with the current standards, and we can certainly expect challenges to a final rule in the future.

For more information about submitting a comment, click here.