A difficult year lies ahead for U.S. fiscal policy. A hoped-for V-shaped recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic has turned into something that looks more like a long-tailed Nike swoosh. Business closings, mostly classed as temporary back in March and April, are, increasingly, proving to be permanent. Evictions and foreclosures loom over cash-poor working-class families, who are estimated to have accumulated as much as $70 billion in back rent owed. Meanwhile, state and local governments, whose spending is constrained by balanced-budget rules, are laying off teachers and firefighters. The trade deficit remains high, and the Fed has no room left to cut rates to stimulate investment.

In a normal world, such a situation would cry out for fiscal stimulus. Ominously, however, the deficit hawks of the Republican party, who slept through the badly timed and budget-busting Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, are starting to stir. They said “No” to any last-minute stimulus before the 2020 election, and their appetite for austerity will be ravenous once they are fully awake.

“But,” you say … “Aren’t the budget hawks right this time? Just look at the numbers!”

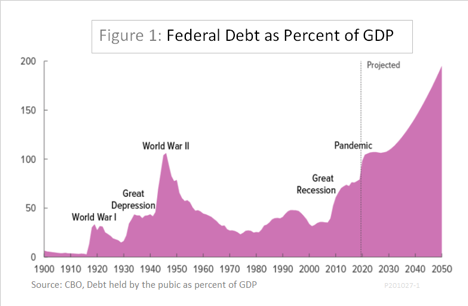

Yes, they are right to point out that under current policies, as measured by the Congressional Budget Office, the federal debt is rising fast. It is about to exceed its previous record as a percentage of GDP, and it is projected to rise for the next 30 years. But those raw numbers tell us little of use for fiscal policy. A rational set of budget rules neither automatically precludes nor condones large budget deficits or a debt ratio that rises over time. To understand what a sensible set of budget rules would look like, read on.

Procedural rules are not enough

Congress does have rules to guide fiscal policy. The 1974 Budget Act specified a set of procedural rules that Congress should follow each year in passing a budget. However, Congress has passed the full set of appropriations bills on schedule only three times in the past 40 years.

Even more problematic is the failure to align annual tax and spending decisions, whether made on time or not, with long-run stability and economic growth goals. Attempts to address that problem have proved inadequate.

Consider the debt ceiling, first enacted more than 100 years ago. Even if we could accurately determine the point beyond which debt becomes excessive (we cannot), the ceiling in its current form is unworkable. Since it is set in nominal terms, with no allowance for inflation or growth of the economy, Congress must vote periodically to raise it. That creates opportunities for various factions to disrupt the budgeting process with brinkmanship over extraneous issues, even though everyone knows that the consequence of not raising the ceiling—default on the debt—would be so dire as to make the whole process a charade.

A more recent type of rule, known as pay-as-you-go, or PAYGO, has fared little better. PAYGO has taken several forms since it was first established in 1990, but the underlying idea is to require that tax cuts or new spending be offset by tax increases or spending cuts elsewhere in the budget. In case the necessary offsets are not made, sequestration — mandatory cuts to already authorized programs — can be invoked to prevent an increase in the deficit. In practice, however, Congress can, and does, waive PAYGO rules whenever it wants to. For example, it used a waiver to allow the 2017 tax cut to go into effect despite the decifict’s resulting increase.

Long-term rules for fiscal policy

If procedural rules are not enough, what would work better? The answer is that if we want a more responsible fiscal policy, we will need to rely less on the short-term impulses of politicians and more on policy rules that target stable, sustainable growth. Here are three suggestions.

Rule 1: First, do no harm.

The economic equivalent of this classic medical maxim is to aim for cyclical neutrality, that is, one that manages taxes and spending in a way that avoids prolonging expansions or deepening recessions.

At first glance, it might seem that the ideal neutral policy would be to keep the budget in balance at all times. A balanced budget amendment aimed at doing just that Is a perennial favorite of congressional conservatives. In reality, though, nothing could be worse. As I explained in an earlier commentary, a balanced budget amendment would be profoundly procyclical. To keep the budget in absolute balance year-in and year-out would require tax increases or spending cuts during downturns and spending increases or tax cuts when the economy was at or above full employment. That would be the exact opposite of “do no harm.”

In contrast, a cyclically neutral rule would take full advantage of so-called automatic stabilizers to moderate the business cycle. Automatic stabilizers are elements of the budget that provide fiscal stimulus during a recession or restraint during an expansion. Examples include the tendency of unemployment benefits to increase and income tax receipts to decrease during a recession.

One form of such a rule would be to hold the budget’s primary structural balance at a constant target value over time. The primary structural balance differs from the ordinary way of measuring the federal deficit or surplus in two ways:

- The “structural” part means that the actual surplus in any year is adjusted to reflect the levels of tax receipts and spending that would prevail, under current law, if the economy were at full employment. During a recession, the actual balance is below the structural balance (that is, further toward deficit) because automatic stabilizers reduce tax revenue and increase spending on income transfers. When the economy is running hot, the actual balance is above the structural balance (that is, further toward surplus).

- The “primary” part of the term means that interest payments on the national debt are disregarded. Although interest payments are a form of government outlay, they are not under the control of policymakers in the short run. Instead, federal interest expenditures are largely determined by market interest rates for any given level of debt.

The primary structural balance target could be set at zero, at a small surplus, or at a moderate deficit. The choice depends on variables like the economy’s long-run rate of growth relative to market interest rates, and whether policymakers want to hold total debt steady as a share of GDP, allow it to grow gradually, or to decrease it. I laid out the details of the math behind the choice of targets in a chapter for the book A Fiscal Cliff published recently by the Cato Institute. (For another version, see this slideshow).

To skip over the equations, at present, and for the foreseeable future, long-term real interest rates in the United States are well below long-term growth of real GDP. Under those conditions, a budget surplus is unnecessary to reduce the debt ratio in the long run. A zero primary structural balance, or even a small deficit of, say, half a percent of GDP, would be sufficient to achieve cyclical neutrality while ensuring that the debt ratio’s current rapid growth would slow over time and, eventually, decrease.

Rule 1a: Emergency exceptions

In the second quarter of 2020, the economic shock of the Covid-19 pandemic drove the unemployment rate to nearly 15 percent and cut 9 percent from real GDP. Under those conditions, automatic stabilizers alone would have caused a sharp increase in the federal deficit. However, the stimulus produced by automatic stabilizers alone would not have been enough to ensure a quick recovery.

The fact is that when the economy encounters a shock so much larger than that of the typical business cycle, we need a degree of fiscal stimulus greater than what primary structural balance rule would permit. At the same time, however, we need some safeguard to prevent waiving the rule for purely political reasons. How could that be done?

One possible emergency exception would be to allow extra fiscal stimulus during periods when interest rates fall to the zero bound, rendering conventional monetary stimulus ineffective. This time around, the Fed cut its benchmark interest rate to zero on March 16, very early in the pandemic. Under the suggested emergency exception, that would have provided room for the CARES Act and other stimulus measures used to counter the effects of the Covid-19 recession. Simultaneously, the rule would not have permitted the excessive stimulus of the 2017 tax cuts, undertaken when the economy was nearing a cyclical peak and interest rates were well within positive territory.

Rule 2: Microeconomic aspects of fiscal policy should be consistent with macro targets

Fiscal policy has both a macroeconomic and a microeconomic side. Rule 1, which calls for cyclical neutrality, serves the macroeconomic goals of stability and growth. Microeconomic issues concerning the structure of taxes and the composition of spending are also important, but they, too, should be approached in a manner that does no macroeconomic harm.

In particular, tax reform, whether aimed at removing perverse incentives or improving distributional equity, should be carried out in a revenue-neutral way over the business cycle. Once again, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 provides a pertinent example. Whether viewed from a conservative or a progressive perspective, a good case can be made on microeconomic grounds to reduce the U.S. corporate tax rate, which was then the highest in the world. However, the economy did not need additional fiscal stimulus when unemployment was low and growth was strong. Instead, cuts to admittedly distortionary corporate-profits taxes should have been offset by increasing other less distortionary taxes, such as the capital gains tax, or by introducing a value-added tax or carbon tax.

Like its distant cousin PAYGO, Rule 2 would require Congress to consider impacts on the deficit when passing tax or spending legislation. However, it differs from PAYGO in two important ways. First, it would be symmetrical. It would bar not only inappropriate fiscal stimulus when the economy is near full employment, but also premature austerity of the kind that was implemented halfway through the recovery from the Great Recession. Second, the degree of offset for tax cuts and spending increases would vary with the business cycle. The required offset would be below100 percent near the bottom of the cycle and over 100 percent at, or near, the peak.

Rule 3: Fiscal rules should be neutral with respect to the size of government.

Conservatives often propose that any fiscal rule should place a constraint on the overall size of government. For example, a 2011 version of a balanced budget amendment proposed capping federal expenditures at 18 percent of GDP. Such a constraint would be a mistake. Instead, any rule governing the path of the deficit or surplus over the business cycle should be neutral as to the size of government as well as neutral concerning the cycle itself.

In reality, there is little evidence to support the idea that small government is necessarily good government. On the contrary, the available evidence shows that broad measures of freedom and prosperity all tend to be higher in countries where governments are larger, not smaller, relative to GDP. Overall, quality of government, as measured by such things as the rule of law, protection of property rights, and government integrity, is more important for freedom and prosperity than the size of government.

What is more, even if one believes, contrary to the evidence, that a smaller government is better, building that objective into a fiscal policy rule would inject a contentious ideological motive into the debate over how best to manage deficits and debts. A rule that is neutral to government size leaves the question of its sizet open to democratic debate, with the provision that new structural spending must be paid for.

The bottom line

The Covid-19 pandemic has revealed a need to rethink many aspects of economic policy. The case for reform is especially strong in the case of budget rules. The purely procedural rules that we have now, such as the debt ceiling and PAYGO, are so full of loopholes as to make them meaningless. Overly rigid alternatives, such as a proposed balanced budget amendment, would do more harm than good, especially when the economy is hit by a shock similar to that encountered in 2020. Yet between rules that are too rigid and rules that are so weak as to be ineffective, there is a golden mean.

Those in charge of fiscal policy could learn a lot about the proper balance between rules and discretion by heeding the Fed’s example. For years, economists who have urged the Fed to follow a more rules-based policy and others resisted those urgings. Frederic Mishkin, a former member of the Fed’s Board of Governors, has argued that rules vs. discretion is not an either-or choice. Instead, Mishkin sees the Fed as moving toward a regime of “constrained discretion” — one that pays attention to rules but permits departures from the rules in response to unexpected economic shocks. He argues that as long as such a regime is backed by transparent communication of policy goals and actions, it can avoid the disadvantages both of pure discretion and of overly rigid rules. In fact, constrained discretion is already the Fed’s all-but-official policy.

Within the context of a primary structural budget rule, there are other things we could do to enhance the economy’s ability to withstand major shocks. In particular, a lot could be done to strengthen existing automatic stabilizers. For example, it would be a good idea to extend unemployment benefits to gig workers. The CARES Act tried to do that, but the effort was not fully successful. A permanent version of payroll protection, perhaps modeled on the German Kurtzarbeit system, would also be helpful. Finally, a healthcare system that did not link insurance coverage to employment would remove yet another source of financial stress to people thrown out of work in a recession.

Now is the right time to start thinking about a better way to handle the next crisis.

This commentary is part of our Captured Economy of Cost Disease series exploring the political economy of debt and deficits. It is made possible thanks to the generous support of the Peter G. Peterson Foundation.