Within two months in 2021, the people of Haiti experienced the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse, and got hit by both a catastrophic 7.2 magnitude earthquake and tropical storm Grace. These events spurred political instability, a spike in gang violence, devastating landslides, and widespread food shortages. Part of the U.S.’s humanitarian response was to issue Special Student Relief (SSR) to Haitian students studying in the U.S., providing them more flexibility in their schedule and eligibility for additional work — relief that the U.S. should extend to other countries with specific designations.

SSR is a regulatory determination issued by the Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) for international students holding F-1 (student) visas. It expands employment opportunities and grants academic leeway for actively enrolled students from countries experiencing critical situations like war, environmental catastrophes, and financial crises. SSR assists international students by providing them the same flexibility that we grant to all U.S. students regarding their coursework and ability to support themselves in school.

Under ordinary circumstances, F-1 students can work for up to 20 hours per week in on-campus jobs. A student can work off-campus for 20 hours per week if they experience severe economic hardship like the loss of financial aid, unexpected medical bills, or an unexpected change in their financial supporter’s condition. Before applying for off-campus work, they must have studied for one full academic year. These students must always maintain a full-time course load. SSR allows students to reduce their course load, enabling them to work more to support themselves financially–provided they can demonstrate that employment is needed to counter “severe economic hardship” directly related to the specific emergent circumstance from their home country.

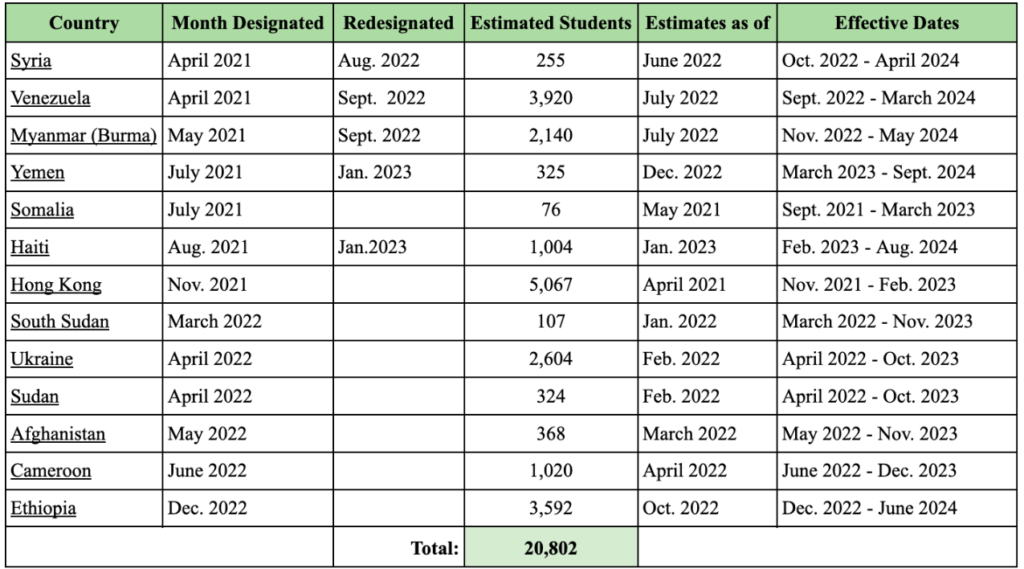

As Niskanen wrote in June, the Biden administration utilized SSR more than any other administration. DHS issued 13 SSR designations since the spring of 2021. Additionally, DHS made five redesignations for Syria, Venezuela, Burma, Yemen, and Haiti in the last six months and recently added Ethiopia. As of January 2023, 20,802 students are estimated to be eligible for SSR. The chart below details the estimated number of eligible students for SSR by country according to announcements made on the Federal Register.

Special Student Relief Designations from Biden Administration

*Data is sourced from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)/Department of Homeland Security (DHS) notices published in the Federal Register

The Biden administration’s current practice is to package SSR with another humanitarian designation, Temporary Protected Status (TPS) (which Niskanen called for in July 2021). This practice makes sense because the criteria for designating SSR and TPS countries are very similar. The latter is extended to citizens of countries experiencing similarly traumatic circumstances, like ongoing armed conflict and environmental disasters.

TPS alone is not enough to protect international students completing their education in the U.S. Though international students can be on an F-1 visa and have TPS simultaneously, they are granted less academic flexibility and ability to work while maintaining F-1 visas that SSR provides. The U.S. should continue to align SSR and TPS designations, so that if a country receives the latter, SSR eligibility should automatically follow.

SSR designations for P-2 Refugee Groups and Countries with DED

In addition to automatically extending SSR to countries with TPS designation, we should also explore extending student relief to more countries without a TPS designation who are experiencing similar humanitarian crises. There is a strong case for extending student relief to any country meeting the “emergent circumstances” eligibility threshold, including countries with groups identified as having a special humanitarian concern (Priority P-2 refugees) and countries with DED.

For example, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) has been plagued by conflict for years — refugees from the DRC constitute the largest refugee population resettled in the U.S. for three consecutive fiscal years. The Department of State has identified Congolese from the Great Lakes region in Africa as a particular humanitarian concern for the U.S. (known as a Priority P-2) group. Yet, the 1,971 students from the DRC on F-1 visas in 2021 did not receive SSR designation.

Similarly, it makes sense to extend SSR to students from countries with Deferred Enforced Departure (DED). Though the U.S. uses DED sparingly, it is typically issued for residents of countries experiencing serious conflict and human rights violations. Hong Kong was granted DED in August 2021 due to emerging — and now realized — human rights concerns. In the DED directive, the President directed DHS to consider granting SSR to Hong Kong (finally doing so in November 2021).

Over the past two years, the Biden administration has utilized SSR more than any previous presidency to protect vulnerable international students. Still, it shouldn’t miss the opportunity to extend automatic protections to countries experiencing hardships that will almost certainly impact students studying in the U.S., regardless of their TPS, P-2, or DED designations. While the administration should be commended for its increased use of SSR, it can and should do more to protect students navigating their U.S. education and turmoil back in their home country.