America’s immigration discourse is dominated by debates over the legality of a travel ban and the cost of a border wall, but other aspects of our immigration system deserve a closer look. The little-known U visa is one such immigration program that helps immigrants and law enforcement alike, but requires some changes to continue to operate successfully in communities across the United States.

The U visa offers temporary legal status to those who are a victim of, or witness to, a crime in the U.S. as an incentive to cooperate with law enforcement in its prosecution, despite their fear of deportation. It is especially helpful for victims of domestic violence, who often fear both deportation and retaliation from their abusers, and is particularly effective in prosecuting gang violence. Agencies using the visa report that individuals are more likely to report past criminal activity, and immigrant crime victims are more likely to reach out to the police, regardless of whether they will apply for legal status.

However, three major issues trouble the program. First, the arbitrary cap on U visa numbers has led to a significant backlog. Second, the Trump administration’s immigration enforcement policies have led to a reduction in applications. Finally, bureaucratic delays hurt the program’s ability to succeed. Increasing the cap and changing enforcement priorities would enhance public safety and provide protection to those who need it.

The Backlog

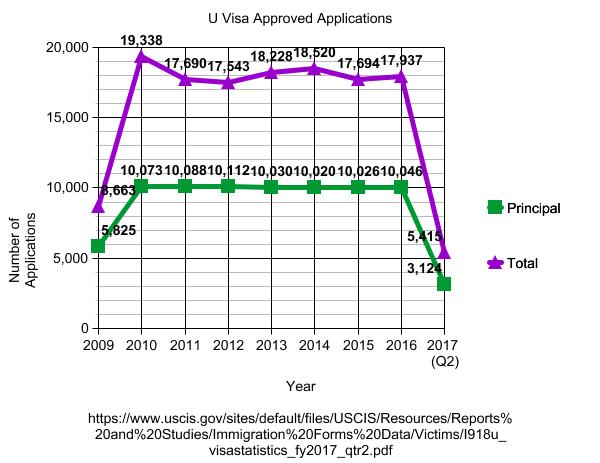

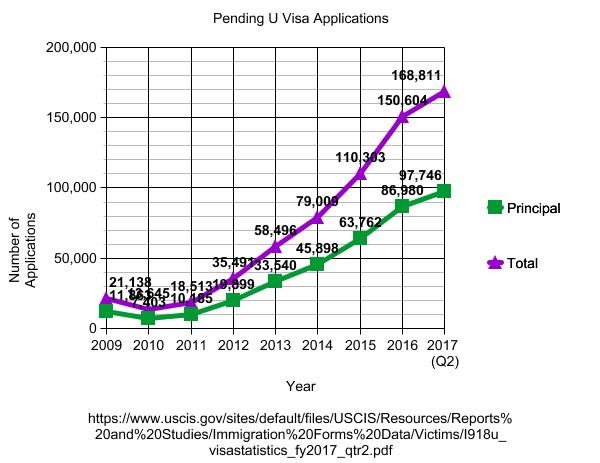

The government offers only 10,000 principal U visas each fiscal year—the cap does not apply to visas given to certain family members of principal recipients—but a backlog of applications still exists. Through March of this year, there were 97,746 U visa applications pending for actual crime victims, and a total of 168,811 applications pending, including family members.

The swelling backlog shows that not enough visas exist to meet the demand for this program. The 2013 immigration reform package included an increase from 10,000 to 18,000 per fiscal year to address this problem. With a backlog three times what it was just four years ago, Congress should again consider raising the cap.

The U visa and Undocumented Domestic Violence Victims

Supporters of the U visa decried President Trump’s immigration enforcement policies, which has led to a decrease in undocumented victims seeking protection.

According to a 2011 study, 75 percent of U visas are granted to undocumented victims of domestic violence. Generally, absent special circumstances or aggravating factors, it is against Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) policy to initiate removal proceedings against an individual known to be the immediate victim or witness to a crime. However, the expansion of enforcement has led many of these individuals to remain silent about abuse, rather than risk deportation.

Their fears are well founded. Undocumented women have been apprehended by ICE at courthouses while seeking protective orders. Abusers now feel emboldened to threaten and retaliate against their victims by reporting them to ICE. Once reported, the victims have little opportunity to seek recourse.

These stories have led to fewer undocumented domestic violence victims seeking U visas because they’re afraid to return home, or reluctant to leave their children. Some have simply dismissed their cases rather than draw attention to themselves. Others file for a T visa instead because, despite having a higher burden of proof, the the wait times to be granted this visa are shorter.

Law enforcement services have also noted a decrease in reported domestic violence and sexual assault crimes this year, thereby reducing the number of people eligible for the U visa. Reports from the Latino population in Los Angeles have dropped 25 percent. Houston, Texas has seen a 42 percent reduction in reported rapes compared to last year. Trafficking hotlines have seen a 50-70 percent decrease in calls compared to last years numbers.

Bureaucratic Delays

In spite of the reduced number of applications for a U visa, the vast number of pending applications has reduced the efficiency of the system. Applicants often wait two to three years without any deportation protection before a decision is made on their application. If their application is approved, the recipients wait one to two more years before they actually receive their visa, though they are granted work authorization and deportation protection in the meantime.

Law enforcement inaction has also created delays. Currently, it takes several months to get an application together, often because law enforcement officers are slow to provide certification that the crime occurred and the applicant was cooperative.

California has made efforts to combat these delays through state law, which requires that law enforcement officers respond to certification requests within ninety days after they are submitted. The law also holds law enforcement accountable by requiring that they submit annual records of applications received, approved, and denied.

The Trump administration has made it clear that combating crime is one of their main focuses. The U visa gives them a tool to fight violent crime and make communities safer, but it remains underutilized. While bureaucratic inefficiencies may not give rise to public indignation, backlogs and delays make victims less likely to come forward. As a result, crimes go unreported and criminals unpunished, making us less safe.

Empowering crime victims to provide crucial information and testimony that helps build the case against violent offenders should be welcomed. It’s time to expand the U visa cap and alter enforcement priorities to provide deportation protection to many more crime victims that can help put violent offenders behind bars.