We have just marked the second anniversary of President Trump’s original travel ban, which resulted in significant negative consequences for immigrants and raised difficult legal questions ultimately heard by the Supreme Court. One impact unknown to many is that the ban magnified America’s rural health care crisis, because it has blocked medical professionals from affected countries from coming to the United States.

The U.S. Census Bureau projects that in the years spanning 2016-2030, the number of Americans age 65 and older will have increased from 49.2 million to 73 million. By that time, there will be a shortage of 42,600-121,300 doctors across the country, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges. The United States simply has too few doctors available to treat its rapidly aging population. Instead of restricting access to physicians, our leaders should seek to recruit and retain foreign doctors. But the travel ban did the opposite.

For instance, Iran, Syria, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, and Yemen — six of the seven countries originally banned — account for more than 7,000 physicians practicing in the United States. In fact, Iran and Syria are two of the top ten nations that supply the United States with physicians.

While doctors from these six countries account for less than 1 percent of America’s total physician workforce, their impact is far-reaching in Rust Belt and rural communities where thousands of residents rely on one specialist for medical care. There, every doctor matters.

For example, Dr. Alaa Al Nofal, a Syrian citizen based in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, is one of only five full-time pediatric endocrinologists in both Dakotas. Many of his patients travel hours for an appointment. Every month, he flies 200 miles by plane to treat additional patients.

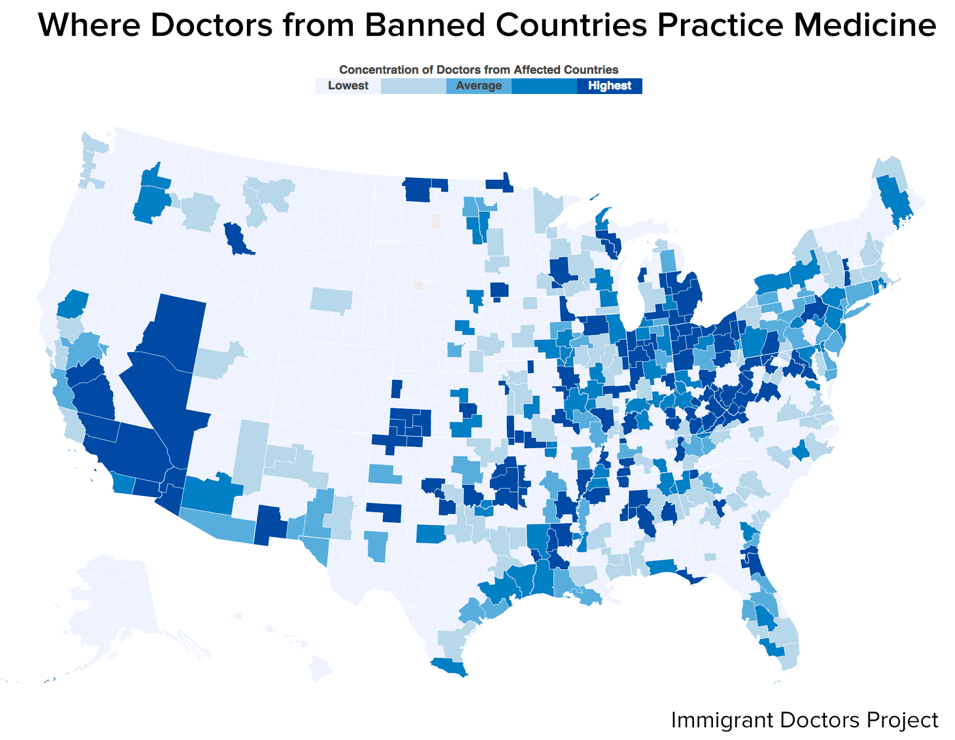

A 2017 analysis by a team of Harvard and MIT economists found that doctors hailing from nations targeted by the travel ban schedule an average of 14 million patient visits each year. On the state level, they provide 1.2 million yearly appointments for residents in Michigan, 880,000 in Ohio, and 700,000 in Pennsylvania. As two of the team members who worked on the study noted, these doctors are frequently “on the front lines of medical need,” working in places where shortages are most severe. While the current ban slightly changed the list of restricted countries, there’s no reason to believe the damage is any less.

Map of areas where doctors from affected countries schedule the most appointments for residents

Photo credit: The Immigrant Doctors Project, obtained from NBC News

Since foreign-trained physicians represent over half of America’s geriatric specialists, one-third of its primary care doctors, and one-quarter of the nation’s total physician workforce, U.S. medical organizations have long understood their role in keeping the country’s health care system afloat. This is why groups like the American Medical Association and the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry have unwaveringly opposed the president’s travel ban.

The Harvard and MIT research team found that the medical specializations most likely to be affected by the ban include fields such as cardiology and neurology. Demand in both of these fields is likely to rise as Americans grow older and develop health complications like cardiovascular disease and dementia.

Moreover, the physician staffing firm Merritt Hawkins finds that 54 percent of America’s cardiologists and half its neurologists are age 55 and older. As more of these professionals retire, communities that rely on a single specialist could lose access to life-saving medical care.

Some may argue that while health care is crucial, stopping the potential threats to public safety from terrorism is most important. But a Cato Institute working paper released in January found no relationship between terrorism and stocks of immigrants from Middle Eastern and North African countries. These findings — and others like it — indicate that the risks of terrorism should not justify outright immigration bans from these nations, especially when such bans cut thousands of Americans off from essential treatment.

The current U.S. visa regime for health care professionals is inadequate, and we should enact comprehensive reforms to recruit, retain, and capitalize on foreign medical professionals. In a Niskanen Center policy brief, Kristie De Peña recommends expanding and reforming the Conrad 30 Visa Waiver, a program that incentivizes foreign doctors to practice in rural areas, as a start.

The administration’s travel ban made the United States sicker and was a poor national security choice. At the two-year anniversary, let us remember the need for evidence-based policymaking and responsible governance, not dangerous rhetoric.

Photo by Павел Сорокин from Pexels