Update: CIS’s Steven Camarota responded to this post here. I replied here.

Last week, U.S. law required President Trump to release his fourth—and possibly final—presidential determination on refugee admissions. The law notwithstanding, he hasn’t released it. Still, it doesn’t take Nostradamus to foretell what it will look like. Reneging on our international (and ethical) commitments by gutting the U.S. refugee program and slashing refugee resettlement to historic lows has been one of the president’s signature policy achievements.

One of the key claims the administration has used to justify its policy is that refugees impose a fiscal burden on Americans. Unfortunately for the administration, their argument lacks any good empirical support.

The best study on the fiscal impact of refugees found their net fiscal impact to be positive, estimating that within 20 years, refugees pay tens of thousands of dollars more in taxes than they receive in benefits. Notably, back in 2017, the administration was caught suppressing a study they had commissioned, on the grounds that HHS was tasked with looking only at the costs of refugee resettlement and not the benefits. HHS had concluded that refugees were a net fiscal boon, bringing in $63 billion more in revenue than they received in expenditures.

If the administration’s own study can’t back them up on the cost of refugee resettlement, just where is a penny-pinching restrictionist to turn?

With little else to buttress the claim, there is one refuge: a report published by the Center for Immigration Studies (CIS) earlier this year. “Because of their low earning power and immediate access to welfare benefits,” the report reads, “recent refugees cost the government substantially more than they contribute in taxes, even over the long term.”

However, the CIS report details a series of decisions that lead to inflated costs and overconfident conclusions.

Inflating Costs by Deflating Education

The CIS report’s basic method of calculating the average refugee cost starts with the estimates of the lifetime fiscal impact of immigrants by age and education from the groundbreaking National Academies report, adds costs for refugee resettlement and welfare, and then applies those estimates to refugees based on their age and education in the 2016 Annual Survey of Refugees (ASR).

The ASR includes a question on educational attainment. Yet rather than rely on refugees’ responses, the CIS report opts to subject their answers to arbitrary cutoffs based on the ASR’s years of schooling question. CIS effectively downgrades refugees’ educational attainment before plugging them into the National Academies model.

For instance, the National Academies would consider a university graduate with a BA after 15 years of schooling, a college grad. CIS, on the other hand, codes the graduate as only having “some college” because they didn’t have a full 16 years of schooling. As for a person who graduated high school and went to technical school with a total of 12 years of education, CIS codes them as having less than a high school diploma because they didn’t complete 12 years of education. Even if they do have 12 years of education, graduated high school, and attended technical school, CIS codes them only as having a high school diploma.

Graduating college in three years, rather than indicating high achievement, instead indicates to CIS that one didn’t really graduate college at all. CIS might be concerned that educational standards in sending countries aren’t as high as the United States. To the extent this is true, it’s hardly relevant, since the NAS model that CIS plugs the downgraded education information into was fit using survey responses itself.

The obvious effect of this maneuver is to understate refugees’ education and increase the resulting cost estimates. The effect is significant, especially at higher levels of education. For instance, CIS’s arbitrary definition of educational attainment would yield only 9 percent of refugees having a bachelors degree or higher, but the true number is over 15 percent. Adjusting for this alone would mean CIS would need to raise its estimate of refugees’ net fiscal impact in the median model by $9,000.

Won’t Somebody Please Think of the Children?

The next factor to consider is that CIS opted not to use the National Academies’ estimate of the total fiscal impact of refugees. Instead, it restricted its analysis to a refugee lifetime. By ignoring the fiscal benefits that come from refugees’ descendants, CIS can claim a much higher degree of certainty around its estimates than is warranted.

Nobody has proposed resettling refugees and barring them from having children. Resettling refugees entails having their descendants as citizens and residents. Excising them from the analysis has little justification.

This decision surely did not arise out of a data restriction. On the contrary, Table 8-12 of the original NAS report shows the total estimated fiscal impact in the first four columns, only then breaking down that total impact into an immigrant component and a descendent component in the rightmost columns.

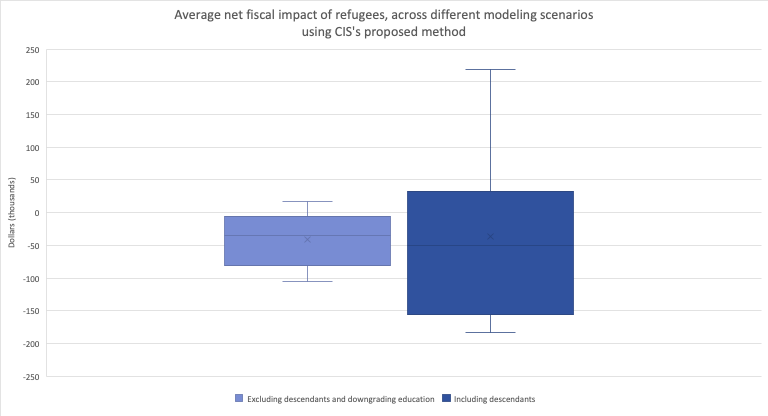

The effect of ignoring the impact of descendants is to drastically shrink the distribution of possible estimates reported by CIS. This is not to say that excluding descendants necessarily increased the estimated costs of refugees. Rather, it increased the uncertainty. Optimistic scenarios look worse by excluding descendants, but pessimistic scenarios look better. The decision isn’t as much an issue of misestimation as it is of overconfidence.

To illustrate: CIS reports that in its most optimistic scenario, the average refugee has a positive net fiscal impact of $15,000. Adding $23,000 in alleged administrative and welfare costs, CIS claims that even the most optimistic assumptions show refugees as a fiscal drain. But if they were to report the total effect, the most optimistic scenario would yield a net fiscal impact before extra costs of $153,000, ten times what it would be without descendants. Adjusting for CIS’s education downgrading, the impact would be $219,000. The $23,000 in extra costs doesn’t make a difference.

Rather, instead of every scenario yielding a negative impact, as CIS reported, the effects of descendants would yield a positive net impact in a quarter of the scenarios, even after the additional costs.

Note: Left plot represents CIS’s estimates. The right plot represents estimates using the same general method as CIS’s, but includes descendant effects and does not follow CIS’s educational downgrading. Author’s calculations, using data from the 2016 ASR and the NAS report, Table 8-12.

What we’re left with is no longer evidence that refugees are a net fiscal cost, but a method that gives an underwhelming spread of possible fiscal impacts on both sides of zero. Accounting for several dubious decisions reveals overstated costs and overstated confidence.