As a strategy for dealing with the Covid-19 pandemic, the Great Barrington Declaration leaves a great deal to be desired. Thanks to the Trump administration’s embrace, the proposal has been roundly condemned by the vast majority of physicians and public health experts, including Dr. Anthony Fauci of the CDC. (And let’s not forget the town of Great Barrington itself). The dominant expert take on the Great Barrington proposal is that it blithely disregards the atrocious death toll that “herd immunity” strategies, such as the Declaration’s “focused protection” approach, are likely to produce. At the same time, the statement egregiously misrepresents the long-term damage the virus might inflict upon those it infects but doesn’t kill. And it seriously understates the danger of the virus to working-age adults.

At this point, it’s not exactly surprising that the freelance musings of three dissident medical researchers would find a receptive audience in the White House. The Declaration is useful as agitprop for the Trump administration. It helps Trump’s proxies and media allies obscure the administration’s catastrophic failure by pretending that its combination of incompetence, neglect, and active interference with state and local disease control efforts was always part of an intentional, coherent strategy recommended by maverick epidemiologists who have broken from the narrow-minded herd.

It’s interesting that the Declaration is the product of the American Institute for Economic Research (AIER), a dogmatically ideological libertarian organization with no real experience or expertise in epidemiology and public health policy. Though it is presented as an ideologically neutral public health proposal of infectious disease specialists with “grave concerns about the damaging physical and mental health impacts of the prevailing COVID-19 policies,” the Declaration would not have been sponsored and promoted by AIER if it did not serve its libertarian ideological agenda. What this ex-libertarian finds interesting–and damning–isn’t just that the Great Barrington Declaration was deemed useful as propaganda by the most illiberal, authoritarian government in living memory, but that it was embraced precisely because it thoroughly embodies some of libertarianism’s worst intellectual and moral tendencies.

Tyler Cowen has written a persuasive and quietly devastating analysis of the Declaration’s many non-medical shortcomings at Bloomberg Opinion. If you haven’t read it, please do. Cowen, who has been either libertarian or libertarian-adjacent his entire life, recognizes that these errors reflect AIER’s rigid libertarian outlook:

The Great Barrington strategy is a tempting one. Coming out of a libertarian think tank, it tries to procure maximum liberty for commerce and daily life. It is a seductive idea. Yet consistency of message is not an unalloyed good, even when the subject is liberty. And when there is a pandemic, one of the government’s most vital roles is to secure public goods, such as vaccines.

The declaration is disappointing because it is looking for an easy way out — first by taking the best alternatives for fighting Covid off the table, then by pretending a normal state of affairs is also an optimum state of affairs.

This is, to my mind, exceedingly gentle. “[C]consistency of message is not an unalloyed good, even when the subject is liberty,” is a generous way to say that purist ideology is a mind-warping reality-distortion field. I entirely concur with Cowen’s piece, but I think it’s worth drawing out further how the Declaration’s errors showcase some of libertarianism’s signature defects.

The thrust of the Declaration is that it’s unnecessary to do anything to prevent the spread of infection other than protecting those most likely to die from the virus. The idea is that eventually, we’ll achieve herd immunity, either because a large majority of the population gets infected and naturally develops antibodies or because a safe and effective vaccine finally becomes available. However, “current lockdown policies … will cause irreparable damage” if kept in place until a vaccine becomes widely available. So lockdown policies need to be scrapped and we should all go back to school, the office, the gym, concerts, football games, and everything else in a hurry, unless there’s a good chance the virus will kill you. In that case, the plan is … Well, it’s not clear what the plan is, except that the vulnerable will need to lock down more intensely than ever while the rest of us endeavor to somehow keep them safe while getting infected.

“Adopting measures to protect the vulnerable should be the central aim of public health responses to COVID-19,” according to the Declaration. However, it offers no assurance that they can be successfully protected when those who aren’t especially vulnerable hasten to “resume life as normal,” as the authors recommend. As John Barry of the Tulane School of Public Health recently wrote in the Times:

One can keep a child from visiting a grandparent in another city easily enough, but what happens when the child and grandparent live in the same household? And how do you protect a 25-year-old diabetic, or cancer survivor, or obese person, or anyone else with a comorbidity who needs to go to work every day? Upon closer examination, the “focused protection” that the declaration urges devolves into a kind of three-card monte; one can’t pin it down.

The idea that we can protect the vulnerable through a strategy that cheers on soaring rates of infection is dumbfounding. It seems that the only way to protect the elderly, immunocompromised, and otherwise at-risk while simultaneously encouraging the spread of infection through the community would be to seal them off from the rest of the population, which simply isn’t possible, practically or politically.

Consider a single mom, Maria, with an autoimmune problem (rheumatoid arthritis, say) who needs to take an immunosuppressant to function as a breadwinner and a parent. Surely it’s better for the whole family if the kids are attending school in the flesh. That means that Maria can support her family by continuing to clean hotel rooms. But now suppose everything simply returns to normal with the conscious aim of getting the bulk of the population infected. How do we protect Maria? She certainly won’t be able to go to work at the hotel to support her kids. And it becomes very likely that her kids will get infected at school, which may not harm them, but could pose a mortal risk to her. In that case, who will take care of them? How will they afford groceries?

Reflecting on cases like these, which could be multiplied indefinitely, the proposal comes to seem pointless. Nobody is going to do this. What’s even the idea here? That a governor or mayor or city council will one day announce that it is now officially a Great Barrington “focused protection” jurisdiction and everyone will just shout “Hurrah!” and sprint to the nearest massage parlor or high step it to the hoe down whilst Maria and the old folks across the street and the neighbor kid with a rare lymphatic disorder …. what? They’re issued impermeable bubbles? We all know that nobody’s getting a taxpayer-funded bubble. And very few of us are willing to simply allow the virus to cull the weak. Which is why next to nobody’s going to try the Great Barrington strategy. And if somebody does try it, it obviously can’t work.

“Young low-risk adults should work normally, rather than from home,” the Declaration’s authors argue. “Restaurants and other businesses should open. Arts, music, sport and other cultural activities should resume.” This is all very easy to say! But you can’t believe most people are actually going to go along with this amid soaring infection rates unless you think people are generally a bunch of amoral idiots.

I’m no angel, but it’s nevertheless important to me, as a matter of elementary moral duty, to avoid becoming a link in a chain of viral transmission that could kill somebody. But even if you’re completely bereft of any sense of responsibility for the lives and welfare of others, it remains that there are plenty of selfish reasons to steer clear of the maskless rager over at the Sig Ep house (an unfortunate reality here in Iowa City.) Lots of folks who get sick from the coronavirus take months to recover. There are widespread reports of lingering neurological effects. The virus seems to cause lasting damage to the hearts and lungs of many who get infected, including in those who showed no symptoms. John Barry notes that “One recent study of 100 recovered adults found that 78 of them showed signs of heart damage. We have no idea whether this damage will cut years from their lives or affect their quality of life.”

So mere personal prudence is enough to lead many of us to decline invitations to weddings, retire our gym memberships, and eschew dine-in restaurants. It’s enough to keep managers and business owners from calling their workers back to the office. Now add a functioning moral compass to mix. In that case, a moderate level of entirely voluntary self-isolation and avoidance of un-distanced and/or mask-free social situations becomes practically inevitable.

Here in Iowa, we’ve never had an official lockdown, and we’ve had very, very few restrictions of any kind. Nobody’s stopping anybody from going to the movies, but nobody goes to the movies. Restaurants are open, but there aren’t many people in them. Indeed, this is the subject of a well-reported story Ben Casselman and Jim Tankersley published in the Times late last week. Here’s how they begin:

As far as the law is concerned, there is no reason that Amedeo Rossi can’t reopen his martini bar in downtown Des Moines, or resume shows at his concert venue two doors down. Yet Mr. Rossi’s businesses remain dark, and one has closed for good.

There are no restrictions keeping Denver Foote from carrying on with her work at the salon where she styles hair. But Ms. Foote is picking up only two shifts a week, and is often sent home early because there are so few customers.

No lockdown stood in the way of the city’s Oktoberfest, but the celebration was canceled. “We could have done it, absolutely,” said Mindy Toyne, whose company has produced the event for 17 years. “We just couldn’t fathom a way that we could produce a festival that was safe.”

It’s hard to tell the practical difference between the Great Barrington approach and Iowa Governor Kim Reynolds’ active hostility to city-level restrictions, mask mandates, and remote schooling. Yet it’s completely obvious, if you live here, that this approach hasn’t put us any nearer to “normal.”

The governor’s aggressively laissez faire approach has delivered some of the country’s highest infection rates, but with very few mitigating economic benefits. I recently visited Massachusetts, which has responded to the pandemic far more aggressively and competently than Iowa has. It now has one of the lowest infection rates in the country, which is why economic and social life there was notably more active and normal than it is here in plague-ridden, anything-goes Iowa. This is not hard to understand. If people don’t feel safe, they won’t go shopping.

Casselman and Tankersley sum it up well:

A growing body of research has concluded that the steep drop in economic activity last spring was primarily a result of individual decisions by consumers and businesses rather than legal mandates. People stopped going to restaurants even before governors ordered them shut down. Airports emptied out even though there were never significant restrictions on domestic air travel.

States like Iowa that reopened quickly did have an initial pop in employment and sales. But more cautious states have at least partly closed that gap, and have seen faster economic rebounds in recent months by many measures.

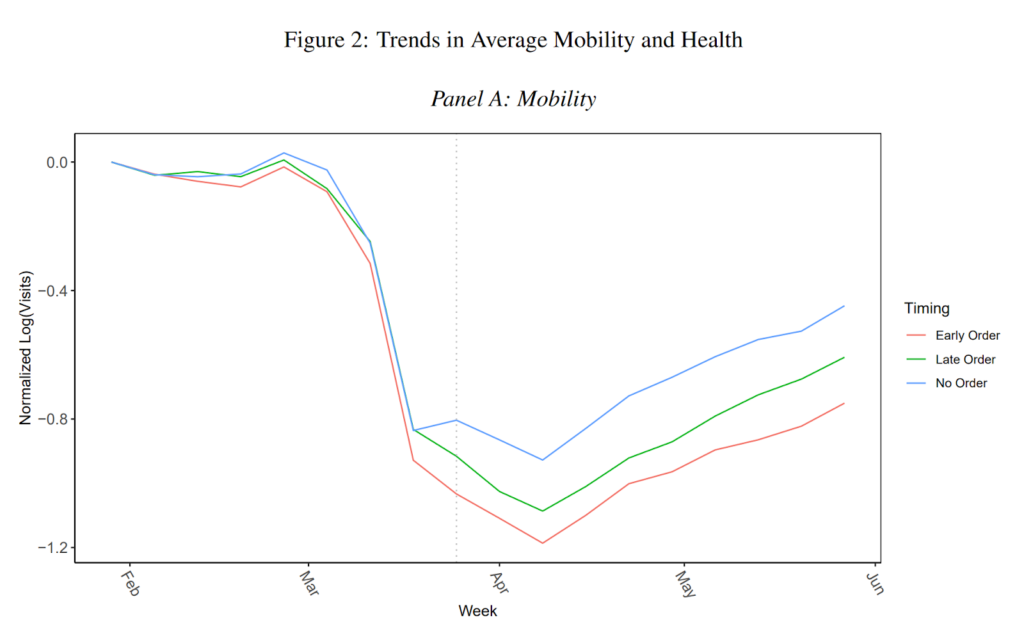

This body of research includes studies like this recent NBER working paper, which takes advantage of huge sets of cell phone location data to confirm that official stay-at-home orders had almost nothing to do with the huge drop in mobility that began in late February and early March. A bit later, there was modest divergence in the rate at which mobility declined between places that had no stay-at-home order, places that issued orders early, and places that issued them late. But it’s evident from the data, illustrated in the chart below, that the slowdown of social and economic life started around same time everywhere regardless of official “shutdown status,” that the slackening of social and economic life reached its nadir at the same time everywhere, and the partial thaw proceeded at about the same pace.

Our infection rate is relatively high here in Iowa. Still, ordinary economic and social life in most respects remains on pause or in low-power mode, so there’s approximately zero chance we’ll get anywhere near herd immunity before a vaccine materializes. There will be no “protection conferred upon the vulnerable by those who have built up herd immunity,” as the Declaration puts it, because we’re not going to get to pre-vaccine herd immunity. And that’s not because anything resembling a “lockdown policy” has been imposed. The bars downtown were packed last Saturday with heedless undergrads cheering at the top of their lungs for the Hawkeyes. They weren’t unwittingly enacting a policy to protect the vulnerable. They’re simply trapping the vulnerable in their houses, stripping them of the freedom to safely undertake activities far more necessary and fundamental than watching the game in a drunken horde. The only reward we’re getting for our laxity is needless fear and death.

So what does any of this have to do with the libertarianism of AIER? Well, libertarians need to believe that, in this case and many others, a policy of doing nothing will work out because they think that government-led efforts (other than the protection of property rights) rarely succeed in improving our lives or securing our freedom. It’s easy to see why it could be thrilling for a libertarian to entertain the idea that, actually, it’s good if most of us just go ahead and get infected with Covid-19. One of the great themes of libertarian thought is that unhindered individual agency and the welfare of society tend to fall into alignment, as if by providence. I’d guess that’s why the authors and advocates of the Declaration studiously ignore actual patterns of individual agency easily observable in places, like Iowa, which have very few restrictions. If they allowed themselves to pay attention, they’d see that the dismal half-life of pandemic America is due more to the invisible hand than the state’s whip hand.

But if you acknowledge that our baleful new reality of Zoom Kindergarten, grocery delivery, and infrequent masked forays into the outer world is more spontaneous than planned order, you’ll have to admit that, when a deadly contagious virus is afoot, unfettered individual choice scales up to a pattern of social life that feels oppressive and suffocating to pretty much everyone. Indeed, libertarians and devil-may-care individualists may feel especially oppressed and suffocated, but they won’t be keen to admit that the scope and value of freedom can shrink without coercion or imposition by the state.

Admitting this would amount to the recognition that patterns of entirely voluntary behavior can leave us less free by closing off options we ought to have. But if you concede that, you’re a mere half-step away from comprehending “structural” or “systemic” oppression.” You might find yourself struggling to deny that the state’s authority can solve otherwise unsolvable collective action problems, supply otherwise unsuppliable public goods, and insure us against otherwise uninsurable risks. You might then become tempted to conclude that not only are we materially better off when the state does all that stuff, we’re also in many respects more free. By that point, hardcore libertarianism is out the window and you’re libertarian-ish, at best. But the ideological mind has a sixth sense for roads to Damascus and can be spectacularly acrobatic in avoiding first steps.

That’s why a proposal released by the libertarian AIER simply can’t be one that accepts that our Covid woes result mainly from millions of voluntary acts of individual prudence and moral duty rather than “government shutdowns.” That’s why the proposal’s advocates can’t seem to grasp that it’s completely infeasible. Nor can a proposal for pandemic response acceptable to ideological libertarians work from the assumption that infectious disease control is a critical public good and that failing to provide it during a global pandemic can destroy millions of lives and trillions of dollars of wealth over generations. A plan that took that for granted would have to assume that we’d be much worse off without a state with ample administrative capacity. It would have to assume that a professional, expert and effective civil service is a profoundly valuable asset, and that our taxes buy things we desperately require and can’t buy any other way.

A plan that takes it for granted that disease control is a crucial public good that the state should provide its citizens might resemble the plans New Zealand, South Korea, Canada and others used to bring their rates of infection down to the point at which more-or-less ordinary social and economic life was able to resume with little risk or fear of either contracting or spreading the virus. Here’s an article about happily concert-going Kiwis.

Remember concerts? In covid-free New Zealand, it’s a reality and not just a memory. https://t.co/P3K1bnyNZM

— The Washington Post (@washingtonpost) October 26, 2020

Read it and weep.

I’ve argued repeatedly that we easily could have done what they did to similar effect. We could have followed our own pre-existing pandemic control plans and implemented a large-scale testing, contact tracing, and supported isolation program. We could have saved a medium-sized city’s worth of American lives as we moved swiftly toward the return of something resembling normal.

That the Trump administration and its allies in the Senate actively opposed efforts to establish a national testing and contact tracing program, and refused to approve sufficient funding for cash-strapped states and municipalities to run their own, in my opinion amounts to a crime against humanity. And it isn’t just a sin of omission. It’s not like the Trump administration was standing idly by as someone was drowning a few feet away. It’s more like a crowd of people started drowning, so the White House tied the lifeguard’s hands behind her back and started pushing poor swimmers into the pool.

It might seem a little ironic that a fundamentally libertarian document like the Great Barrington Declaration would be deployed in an attempt to obscure the enormity of the American state visiting mass death upon the American people. But it’s not really ironic at all. A state that kills its citizens by hobbling mechanisms created to protect them in times of crisis will always find allies in ideologues who believe that those mechanisms should not exist, that we’d be better off without them, and that it’s tyranny to collect the taxes that buy them.