Insurance plays an essential role in any market economy. By spreading losses among members of a group with similar exposure, insurance encourages people to take prudent risks while protecting them from financial ruin in case they are the unlucky ones. But not all insurance is equal. Sometimes, rather than representing the public interest, a public insurance program can come to represent a special interest subsidy in disguise. Crop insurance, the multi-billion-dollar government subsidy that lies at the heart of the farm bill that is now working its way through Congress, is a case in point.

Let’s take a look at the strange economics of crop insurance, and what can be done to fix it.

Crop losses are not an insurable risk

The problems of crop “insurance” begin with the fact that crop losses are not really an insurable risk. Crop insurance violates three of the most important rules that economists have developed to identify which risks are insurable and which are not.

First, to be insurable, losses should be fortuitous — the result of events that are outside the control of the insured party. Some crop losses (for example, damage from hail or tornados) fit this definition. They strike randomly. However, many other risks depend on the choice of farming practices, which, in turn, are influenced by the presence of insurance.

The tendency for people who are protected from loss by insurance to take greater risks is known as moral hazard. Commercial insurers guard against moral hazard as best they can by encouraging practices that reduce losses. For example, you can get a discount on your home insurance if you have a smoke alarm and security system. However, as the National Resources Defense Council explains in a recent report, rules of the federal crop insurance program encourage risky practices, such as planting crops on lands that are poorly suited for them. Rather than encouraging loss mitigation practices such as diversification and planting cover crops, crop insurance discourages them. When crops are planted that are likely to fail, resources are wasted and program costs soar.

Second, insurance is normally limited to situations in which people face a pure risk; that is, a risk of loss that is not offset by a hope of gain. For example, if I insure my house against fire, I either experience a fire, in which case I suffer a loss, or I do not, in which case I have neither a loss nor a gain. In contrast, speculative risks carry a chance of gain as well as loss. If I plant a field of corn, I may suffer a loss if the weather is bad or prices are low, but if the harvest and market conditions are good, I expect to make a profit. Insurers have traditionally been unwilling to cover speculative risks. Other financial mechanisms, such as futures- and options-markets, are more suited to that job.

Third, in order for a risk to be insurable, it must be possible to establish a premium that is affordable to the party seeking coverage, yet high enough to cover claims and the administrative expenses of the insurer. That is not possible for crop insurance. Due to the prevalence of moral hazard and the speculative nature of the risks, an actuarially fair premium for crop insurance would be unaffordable.

Together, moral hazard, speculative risks, and lack of affordability make crop “insurance” a sham. It is able to exist only because the government subsidizes more than 60 percent of the cost of the program. It is the subsidy, not the insurance that makes the program so popular with farmers.

Benefits are skewed toward the largest farms

People seem to like farmers. A recent industry-commissioned public opinion poll found that 86 percent of those questioned had a favorable opinion of farmers. More than 90 percent thought that it was important for the federal government to spend money to support them. Favorable responses varied hardly at all among Republicans, Democrats, and independents.

Why the popularity? One item in the poll gives us a clue: More than two-thirds of those polled disagreed with the statement, “Most of our nation’s food is grown by farming corporations that can easily afford to pay for their own crop insurance premiums without taxpayer money. It is the responsibility of any business to protect itself with insurance, and farmers should not get special treatment that the federal government simply cannot afford.” It seems likely that the disagreement reflects a widespread perception that the principal beneficiaries of crop insurance are small family-farms that would face a high risk of failure without subsidized crop insurance. However, the numbers, as reported for 2016 by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, do not support that view.

The first source of confusion arises from the notion that “family farms” and “corporate farms” are two different things. It is true that the USDA classifies 99 percent of all farms as “family farms.” However, it applies that term broadly to “any farm where the majority of the business is owned by the principal operator — the person most responsible for running the farm — and individuals related to the principal operator.” In practice, many such farms, including most large family-farms, are legally organized as limited-liability corporations or partnerships. Contrary to what farm lobbyists would like us to think, “corporate farms” and “family farms” are not separate categories.

According to USDA data, less than half of all farm output is produced by farms that are organized as traditional sole proprietorships. What’s more, most small farm-proprietorships are not the primary source of incomes for their owners. Some 18 percent of small family-farms are operated by people who report that they are retired, and another 42 percent report a nonfarm occupation as their main source of income.

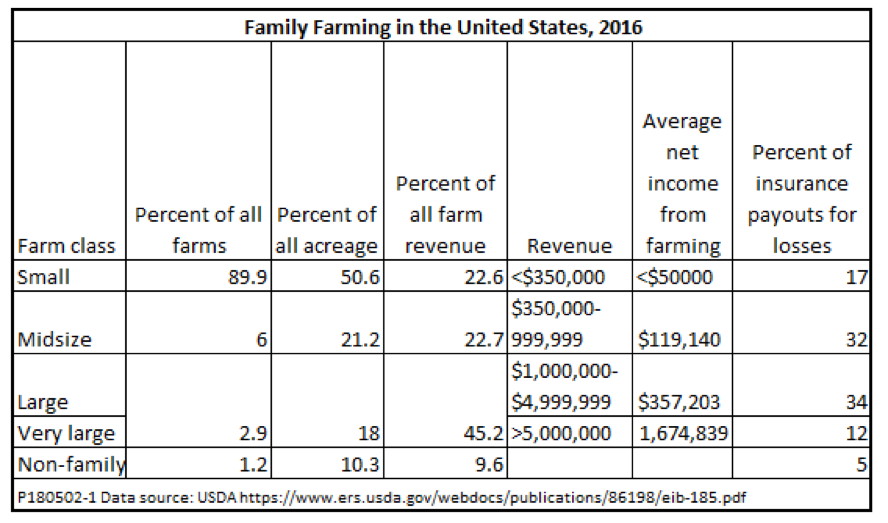

As the data in the following table show, small family-farms — those with gross sales less than $350,000 — are not, on average, very profitable. Even when we exclude the 60 percent of small family-farms run by retirees or people with other principal jobs, the average farm income earned by farm households is less than $50,000. Some 80 percent of such farms have an average operating profit margin (OPM) — defined as revenue less operating costs — below 10 percent, putting them at high financial risk by USDA standards. Yet, despite facing the highest financial risk of any farms, they receive just 17 percent of all insurance payouts for crop losses.

Midsize farms are more prosperous, averaging some $120,000 of household income from farming. Only about 40 percent of them are in the high-risk category. Another 20 percent face moderate financial risks, with OPMs between 10 and 25 percent. These midsize farms, which account for 6 percent of all farms and 21 percent of all acreage, receive 32 percent of crop insurance payouts.

The 2.9 percent of family farms that are classified as large or very large exist in a different world. Large farms each have more than a million dollars in sales, and average $357,000 in annual household income. Those that are very large each have more than $5 million in sales and average $1.7 million in household income. More than half of large farms and more than 40 percent of very large farms fall in the low-risk category, with OPMs of 25 percent or more. Together, these high-income, low-risk family farms received 46 percent of all crop insurance payouts. If we add in non-family farms, which are also very large, on average, we find that just 4.3 percent of all farms receive more than half of all crop insurance payouts.

Finally, it is worth noting that crop insurance benefits are not only skewed toward the largest farms, but are also skewed toward just a few crops. In principle, insurance is available for over 100 different crops, but according to data from the Congressional Research Service, between federal crop insurance and other subsidies provided by the Commodity Credit Corporation, corn, wheat, and soybeans accounted for 77 percent of all support payments. Adding cotton, rice, and peanuts brought the total to 94 percent. Yet these six crops accounted for just 28 percent of total farm output in that year. The millions of farmers, large and small, who produce the milk, beef, eggs, tomatoes, lettuce, and other things you eat receive little or no support from crop insurance and the like.

If we add all these facts together, it becomes much harder to disagree with the proposition that “most of our nation’s food is grown by farming corporations that can easily afford to pay for their own crop insurance premiums without taxpayer money.” The data speak for themselves: The great majority of American farm output is produced by farmers who are, or should be, willing to accept “the responsibility of any business to protect itself with insurance” without special subsidies from the federal government.

What can be done?

The obvious thing would be to phase out the federal crop insurance program altogether, giving farmers reasonable time to adjust their mix of crops, farming practices, and financial arrangements. Short of that, critics of crop insurance offer a number of reforms that would make the program less costly to taxpayers and less disruptive to markets. Here just a few ideas from some of the most prominent liberal and conservative critics:

Eliminate yield exclusion. Premiums for crop insurance are adjusted according to each farm’s past yields. The idea is a reasonable one — farmers that have a record of consistently good yields and less frequent crop failures should pay lower rates for insurance than those with consistently poor yields and high losses. However, in calculating average yields, the government allows farmers to exclude as many as 15 low-yielding years from the average. The exclusions exaggerate past performance, artificially lower premiums, encourage farmers to plant risky crops, and increase payouts. Recommendation: Base premiums on true average-yields without exclusions. (Natural Resources Defense Council)

Stricter caps for subsidies. The 2014 farm bill, which the new version will replace, attempted to place caps on the subsidies that could go to the largest farms. However, it left many loopholes. One of the largest loopholes was the ability of large farms to form “pass-through entities” that allowed them to split total farm income among family members. Far from fixing this, the 2018 bill would widen the loophole by adding nephews, nieces, and cousins to the siblings and adult children who can already share farm income.

Recommendation: Make the caps realistic. (Environmental Working Group)

As the small-farmer advocacy group Center for Rural Affairs puts it,

Unlimited crop-insurance-premium subsidies are a loophole that allows the largest farmers to reap the greatest benefits from government subsidy. That is why we support capping crop-insurance-premium subsidies at $50,000. We believe that crop insurance should be a safety net, not a government subsidy to finance unlimited expansion.

Limit protection to yields, not revenue. If the government is to offer any protection against farming risk, it should focus on risks to crop yields from droughts, tornadoes, pests, and other natural hazards, as opposed to risks to the profitability of a given yield arising from market conditions. That would mean eliminating programs like Agricultural Risk Coverage, which protects farms from even “shallow” losses in revenue. “Any myth that commodity programs are supposed to be a safety net as opposed to an income guarantee gets quickly dispelled by this program.” Recommendation: Limit coverage to loss of crop yield. (Heritage Foundation)

Eliminate the Harvest-Price Option. Under standard insurance, a farmer would be compensated for crop losses at the price prevailing at the time of planting. Presumably, if that price had not been high enough to offer a profit, the farmer would not have planted, or would have planted something else. Under the Harvest-Price Option included in subsidized policies under the current farm bill, compensation is based on the higher of the price at time of planting or the price at the time of harvest. That is not only costly to the government, but it duplicates protection that could be obtained through futures- and options-markets without government assistance. Recommendation: Eliminate the Harvest-Price Option. (American Enterprise Institute)

The Bottom Line

Crop “insurance” is not true insurance. It is sham insurance that could not exist without government subsidies. Although the iconic small family-farm is often invoked in the program’s defense, its primary beneficiaries are, in practice, the largest and wealthiest farms — huge limited-liability corporations and other tax-advantaged pass-through entities that are “family farms” only in name. Outside the favored sectors of corn, wheat, and soybeans, the vast majority of American farmers and ranchers manage the risks of farming without subsidized insurance. As passed out of committee, the 2018 farm bill is no better than the old one, but there is still a chance to fix it while it is open for debate on the floor. Seize that chance!