Previously in Niskanen’s ongoing sanctuary city series, we discussed why local law enforcement may be hesitant to comply with detainers issued by ICE (not least of which are the costly legal ramifications). In this piece, we take a step back and discuss what exactly ICE immigration detainers are, and how they differ from judicial warrants.

A warrant is a written order signed by a court that validates any search, seizure, or arrest by local law enforcement. It must always be accompanied by a sworn statement made by an officer under oath, claiming that probable cause that a crime was committed exists.

On the other hand, an immigration detainer from ICE is a request mechanism where local law enforcement agencies are asked to hold — or detain — individuals suspected of an immigration violation for 48 hours after their otherwise lawful release from custody. ICE cannot step in while any criminal charges are pending. Rather, ICE must wait until the individual is no longer being held on local law enforcement authority. ICE immigration detainers are mostly used to facilitate a transfer of individuals from local law enforcement to ICE after the local agency’s justification for holding an individual has expired.

Whereas a warrant requires review and approval by a judge, an ICE detainer can be issued by just about any immigration official when a person suspected of not having lawful immigration status is arrested by local law enforcement. Federal information-sharing agreements have existed between immigration authorities and the FBI for decades. Per these agreements, fingerprints that the FBI collects from local law enforcement are automatically forwarded to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). DHS then checks against immigration databases, revealing whether an individual is unlawfully present, and whether they present a risk to public safety.

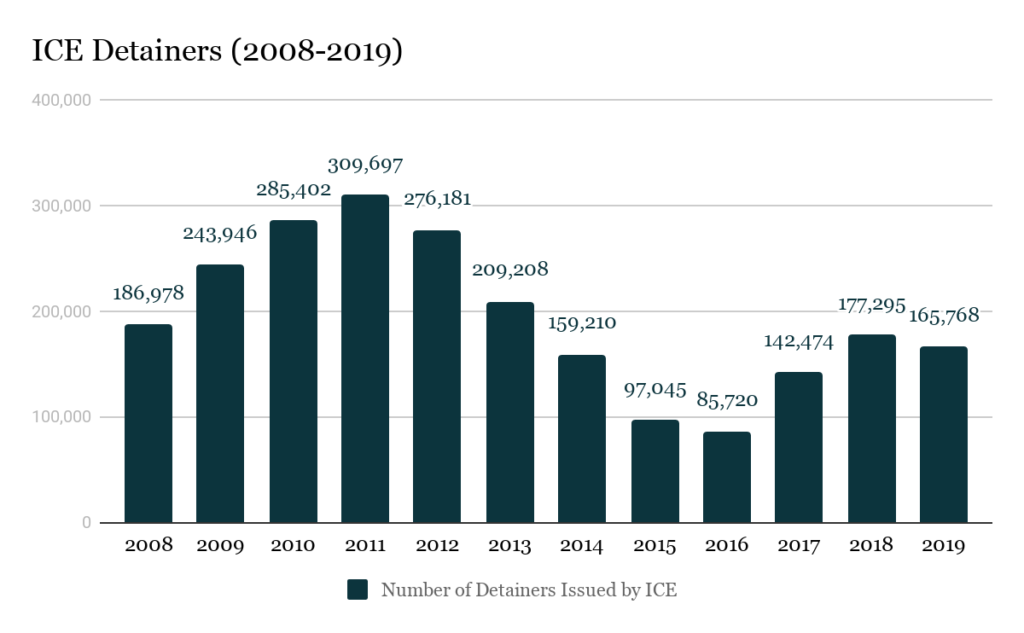

Authorization for issuing immigration detainers lies in Title 8, Section 287.7 of the Code of Federal Regulations, and the Immigration and Nationality Act. Authority to issue a detainer is broad. The law allows border patrol agents, aircraft pilots, special agents, deportation officers, immigration inspectors, adjudications officers, immigration and supervisory enforcement agents, supervisory and managerial personnel of any of these people, and almost any immigration officer who “needs” it, the authority to issue a detainer. Though the regulation requires the receiving law enforcement agency to comply with the detainer “request,” numerous courts have not enforced the requirement. Per the policies reinstated by the Trump administration in 2017, any individual suspected of lacking lawful status is a priority for removal, regardless of their threat — or lack thereof — to public safety. In recent years, the number of detainers has steadily gone up. Still, the number of detainers issued under the Trump administration is dwarfed by those issued during the Obama administration. It may surprise some that at their height, deportations under the Obama administration — just before their change in enforcement policies — nearly doubled the number of deportations in 2019.

The detainer process extends significant deference to immigration officials, as opposed to a warrant, which extends deference to the individual via protections enshrined in the Fourth Amendment. Prior to 2014, ICE officials could issue a detainer if they had “reason to believe” an individual was removable. After several successful lawsuits, the Obama administration rolled back its use of detainers, asking instead to be notified when a local agency was preparing to release an alien. If agents could not take custody of that person before the scheduled release, they could request extended detention — but still had to confirm there was a final order of removal, or other “probable cause” that justified removal.

Making the process more intentional (rather than automatic) likely spurred the falling numbers of detainer requests between 2014-16, in addition to the new probable cause requirements. The subsequent rise in detainers during the Trump administration is likely due to the sheer number of individuals detained after the administration’s 2016 removal of prioritization categories.

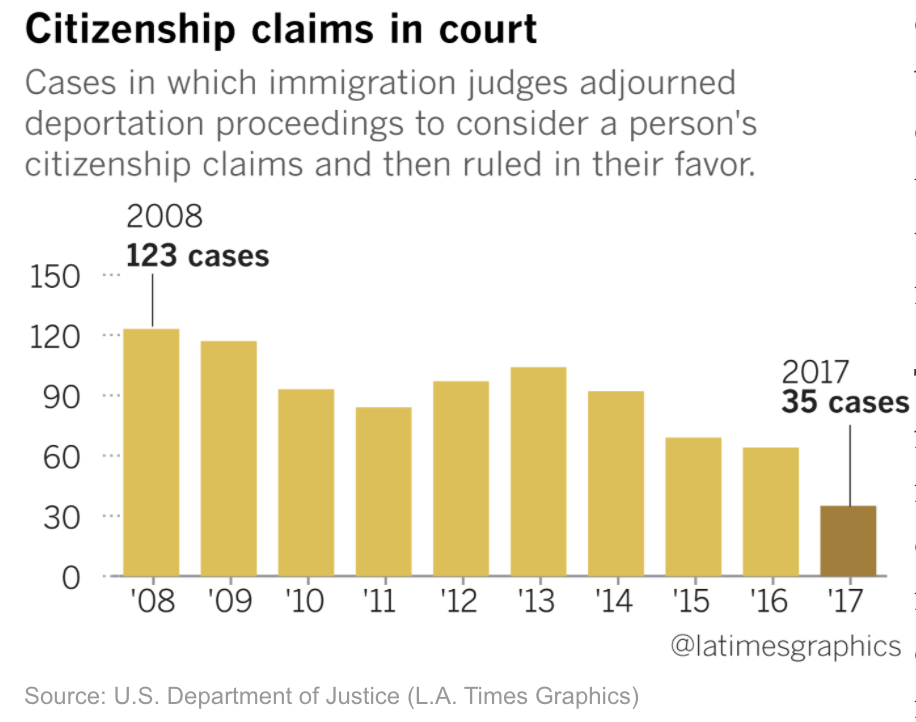

Importantly, the confirmation that there is a civil order of removal or other probable cause still does not alleviate concerns by local law enforcement about detaining individuals at the request of ICE without a warrant. These overt safeguards are intended to protect individual rights from potential abuse by law enforcement officers. Still, no appeals court has authoritatively ruled on whether it provides local law enforcement the legal cover necessary to hold individuals beyond their scheduled release in compliance with an ICE detainer. It doesn’t help matters that ICE has made numerous documented mistakes when it comes to arrests and detentions. According to the Los Angeles Times, since 2012, ICE has detained more than 1,480 people to investigate their citizenship claims — only to later release them from its custody. Here are the agency figures provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and reproduced in the L.A. Times graphic:

In one case, an American citizen was held for over three years — 1,273 days — in detention because ICE did not believe him to be a legal citizen. He was awarded a $20,000 settlement.

Investigating citizenship claims can be arduous, particularly for those who do not have paper records of their citizenship readily available. Sometimes though, ICE could correct these mistakes by conducting more than a cursory review of records before issuing a detainer. These mistakes leave significant questions as to the efficacy of what the ICE immigration detainer system is trying to accomplish.

It follows that local law enforcement may be more willing to cooperate with federal immigration officials if they had more confidence in what ICE detainers are trying to accomplish. Significantly raising the requirements to issue detainers — both who can authorize their issuance and what the standard of review is to do so — or doing away with them entirely and replacing them with warrants — would ensure more human rights protections, fewer lawsuits, and a tailored focus on priority detainees.