“Remember the old saying that ‘an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure’?” asks United Healthcare. “Maintaining or improving your health is important – and a focus on regular preventive care, along with following the advice of your doctor, can help you stay healthy … Routine checkups and screenings can help you avoid serious health problems, allowing you and your doctor to work as a team to manage your overall health, and help you reach your personal health and wellness goals.”

You would think that a private insurer, on the hook for big claims down the road if preventive measures did not catch health problems early, would know, if anyone did. Popular opinion seems to agree. Readers of some of my own earlier healthcare posts have often offered opinions such as, “A couple hundred dollars of preventive medicine will prevent tens to hundreds of thousands of dollars being spent,” and, “Anyone who has ever visited a physician knows that preventive care is cheaper in the long run.”

But there is more to the story. Yes, healthcare reform needs to get preventive care right, but preventive care by itself will not make us healthier and cut national healthcare spending. Here are some of the issues.

Preventive care is not just about saving money

The “ounce of prevention” cliché suggests that preventive care is mostly about saving money, but it is more accurate to say that it is about spending money efficiently. If we look at actual data on effectiveness of preventive care we find that even though it does not often reduce total healthcare spending, even when it does not, it can be very much worthwhile.

First, though, we should clarify just what the term means. Primary preventive care aims to keep a disease from developing in the first place. Childhood vaccinations, smoking cessation, and good diet are examples. Secondary prevention means catching a disease in its earliest stages so that timely treatment can minimize the consequences, for example by screening for early detection of cancer or high blood pressure. Tertiary prevention means taking measures to arrest or slow the progression of chronic diseases like diabetes or HIV that cannot be fully cured with current treatments. The term “preventive care” without qualification usually refers to a combination of the primary and secondary categories — a usage we will follow here.

Health economists often measure the payoff to preventive care in quality-adjusted life years, or QALYs. QALYs weight years of extended life according to their comfort and restrictions on activity. For example, a year spent in a hospital bed might count just half as much as one spent in perfect health. Beyond the payoff in QALYs, preventive care has subjective payoffs, such as the peace of mind that comes when a cancer or heart-disease screening comes out negative.

Childhood vaccinations are an example of preventive care that does have the potential to save costs. Vaccinations reduce the cost of treatment for people who, without them, would later develop the disease in question, and they also reduce the spread of contagious diseases in the population at large. They are so inexpensive and so effective that vaccinating as large a share of the population as possible reduces total healthcare expenditures. Intervention to discourage smoking is another example of preventive care that has the potential to reduce total healthcare spending. A 2010 study by Michael V. Maciosek and colleagues identified twenty preventive measures that could reduce total spending if more widely used as a package, although not all would save costs individually.

More commonly, however, providing preventive care improves health but increases total spending. For example, colonoscopies can detect cancer at an early stage and improve the chance of a cure. However, colonoscopies are expensive, many people are tested who turn out to be cancer-free, and occasionally the tests themselves can cause costly complications. Similarly, taking statins to lower cholesterol reduces the incidence of heart attacks, but statins themselves are costly. Some people who take statins die of other causes before they get a heart attack; some suffer heart attacks despite taking statins; and others suffer side effects of the statins themselves that require further treatment. On balance, both colonoscopies and use ofstatins can be cost-effective ways of improving quality of life and preventing premature deaths, but the more widely their use is expanded to parts of the population that are at lower risk, the more likely they are to increase, rather than decrease, total spending.

In some cases, overzealous application of preventive measures can both increase total healthcare costs and lead to worse health outcomes. Widespread screening for prostate cancer, followed by aggressive treatment of the disease in its earliest stages, has been found to fit that pattern, at least according to some studies. Routine use of PSA tests to screen for prostate cancer has fallen into disfavor, and a policy of “watchful waiting” is often recommended when early symptoms are detected. For women, many practitioners no longer consider annual Pap tests and mammograms necessary for older patients with no histories of the relevant cancers.

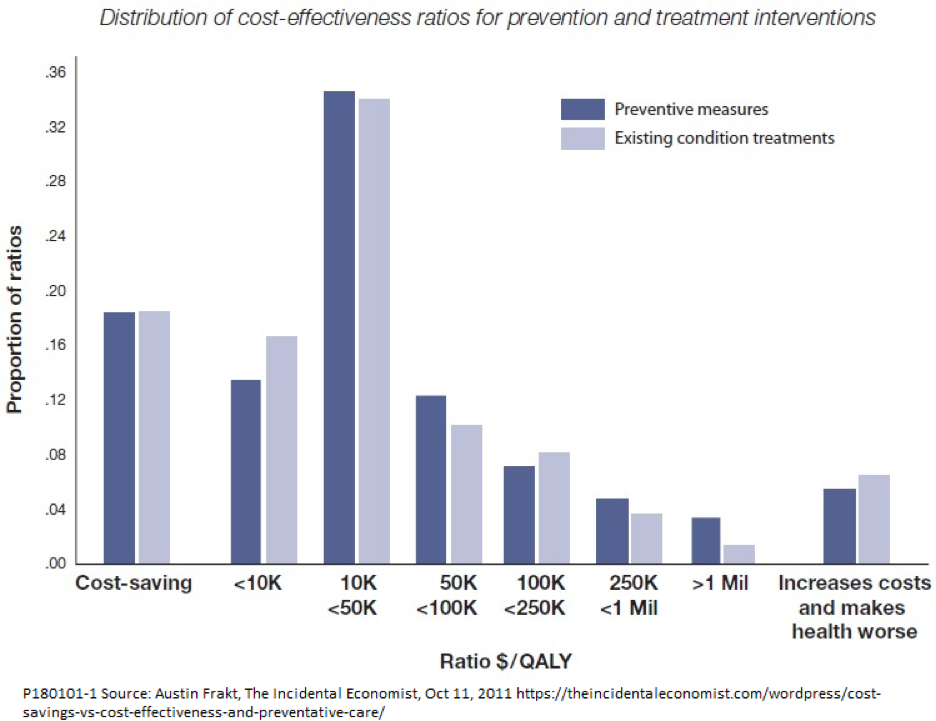

On balance, the range of cost-effectiveness for different kinds of preventive care is not all that much different than that for treatments for existing conditions. The following chart, provided by health economist Austin Frakt, shows the wide range of cost-effectiveness for both categories.

The chart is based on a review of 599 individual cost-effectiveness studies published in the New England Journal of Medicine. The treatments and preventive services are rated in terms of their cost in dollars per added quality adjusted life year. There is no universally agreement over the dividing line between “cost-effective” and “not cost-effective,” but some health economists consider $100,000 per QALY to be a reasonable rule of thumb.

Note that the dark- and light-blue bars are sorted by cost-effectiveness, not by the type of disorder. For example, the dark bars in the <10K column may refer to preventive treatments for a completely different set of conditions than the light bar in the same column. In the case of any given condition, prevention might be much more, or much less, cost-effective than waiting for the disease to develop and then treating it.

As the chart shows, less than a fifth of interventions are actually cost-saving, in the sense of reducing total healthcare expenditures. However, most preventive measures and most treatments studied are cost-effective, in the sense that the extra money spent produces a positive return in terms of QALYs — a very good return, in many cases.

Should preventive care be shielded from cost sharing?

Preventive care does not pose any special problem for policy reforms that would provide first-dollar coverage for all health needs. However, plans that require substantial cost sharing in the form of deductibles or copays need to consider whether to make special provisions for preventive care.

The simple answer would be to waive cost sharing for all cost-saving preventive services and subject other preventive care to the same copays and deductibles as treatment of existing conditions. Encouraging maximum use of cost-saving preventive services would be in the interest of any public or private insurer as well as that of the insured.

The Affordable Care Act recognizes that principle by exempting a list of primary and secondary preventive services from copays and deductibles. Other reform plans, such as the Medicare Extra proposal from the Center for American Progress and the universal catastrophic coverage plan proposed by Kip Hagopian and Dana Goldman also include provision of selected preventive services at no cost to the user.

Whether to expand waivers of copays and deductibles beyond preventive services that actually save costs raises additional problems. One is that consumers do not seem to be very good at determining what kinds of care are worthwhile and what are not. A recent survey of the literature finds that cost sharing does lower total healthcare spending, but the reductions come both from appropriate and inappropriate care. The appropriate care that people with high copays and deductibles often skip includes not only primary and secondary preventive services, such as vaccinations and screenings, but also tertiary preventive care, such as medications and periodic checkups to control chronic conditions like diabetes and hypertension.

The study by Maciosek et al., cited above, provides some additional indirect evidence on consumer behavior. The authors of that study looked at two scenarios in evaluating the cost-effectiveness of their package of 20 preventive services. One scenario was an increase in use of the services from zero to 90 percent of the population. The other was an increase in use from current levels to 90 percent. On the face of it, it would seem that the people who now use these preventive services would be those who would derive the greatest benefits relative to costs, while those who didn’t use them would be those with smaller benefits relative to costs. That, in turn, would suggest that the incremental ratio of benefits to costs for the scenario that started from current rates of usage would be lower than the ratio for the zero-base scenario. In fact, the Maciosek study found the opposite to be true. Their results suggest that people who now forego preventive care would, in fact, derive greater net benefits than those who now use it.

Measures to improve transparency and competition would be one way to help consumers make better choices for preventive care, and for other healthcare services, too. John Goodman, an advocate of market-based healthcare reform, describes the problem in these terms:

Because we’ve suppressed the market, no one ever sees a real price for anything. No patient, no doctor, no employer, no employee. What we have is a bureaucratic system that gives us all perverse incentives. And when we act on those incentives, we make costs higher, quality lower, and access to care more difficult than otherwise would have been the case.

Goodman applauds the growth of walk-in clinics, telephone and e-mail consultations, online pharmacies, and other innovative care options as steps in the right direction. Conservative and progressive critics agree that the present system, in which consumers are bombarded with television ads for medical services of all types, but are often unable to receive straight answers from insurers, doctors, or hospitals about costs and risks, is not doing its job.

Measuring cost-effectiveness of preventive care

In order to deciding which preventive services to provide free of charge and to keep patients well informed about their options, we need to be able measure the cost-effectiveness of those services. That is not always easy.

The problems of measuring cost-effectiveness are succinctly summarized in a 2014 Health Affairs article by Mark V. Pauly, Frank A. Sloan, and Sean D. Sullivan. The article notes that the list of required preventive services under the ACA is based on recommendations of two federal panels, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices and the Preventive Services Task Force. However, neither body is explicitly required to take a cost-benefit approach in making recommendations. Their members consist principally of people with medical training, and their decisions tend to emphasize clinical considerations, with cost-effectiveness considered on only an ad-hoc basis.

Pauly and colleagues recommend that the current evaluation procedure be replaced by one that explicitly includes cost-benefit analysis, and offer several suggestions on how such a proposal might be implemented. They propose more than a yes-no assessment of whether or not a given preventive service saves costs. Rather, they suggest giving each preventive service one of three levels of recommendation:

- A strong recommendation would carry the expectation that physicians would routinely offer and encourage the use of the service, and that insurance or public subsidies would reduce the user price to zero.

- A permissive recommendation would emphasize the positive health benefits of the service. It would encourage providers not only to alert patients about its availability and cost in general, but to counsel them about its suitability for them as individuals. However, there would be no requirement to waive cost sharing.

- A discouraging recommendation would be given to services that are found to be clinically ineffective or not effective enough to justify the cost for the great majority of people.

The classification could be based, at least in part, on specific cost-effectiveness thresholds. For example, procedures with a cost of less than $100,000 per QALY might get a strong recommendation, those in a range of $100,000 to $300,000 per QALY a permissive recommendation, and those over $300,000 per QALY a discouraging recommendation. Setting the thresholds would be a political decision, rather than a clinical or economic one.

The strength of the recommendation for a service would also depend, in part, on how broad a subset of the population might benefit. Services that would benefit almost everyone, such as childhood immunizations, would be more likely to get strong recommendations. Permissive recommendations would be more appropriate for services that might be of great benefit to some people but not to others. For example, vaccination against yellow fever is recommended for travelers to Panama but not for travelers to Norway. Discouraging recommendations would signal that few people would be likely to benefit from the service, but their use would not be prohibited. People who wanted to pay could give them a try.

Implications for policymakers

This discussion has several implications for policymakers.

First, any reform plan that includes substantial cost sharing (for example, universal catastrophic coverage or Medicare Extra) should waive copays and deductibles for cost-saving preventive services. Consideration could also be given to adding other high-value preventive services to the list even if they do not reduce total healthcare spending.

Second, current institutions for evaluation of cost-effectiveness are inadequate. At a minimum, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices and the Preventive Services Task Force should be directed explicitly to include cost-benefit considerations in their recommendations. Ideally, these panels should be restructured and provided with greater resources, including expertise in economic as well as clinical aspects of preventive care.

Third, reform plans should include measures to improve consumer decision making about preventive care. In addition to better information about cost-effectiveness, those measures should include greater pricing transparency, greater competition, and encouragement of new forms of preventive care delivery, such as walk-in clinics and online consultations.

Better preventive care is not a magic bullet that will solve all the problems of cost and quality of the U.S. healthcare system. However, it has an important role to play and deserves the special attention of reformers.