Although there is a growing consensus that deep reductions in greenhouse gas emissions are necessary in order to reduce the impacts of climate change, the hurdles to enacting any meaningful climate change mitigation policy remain strong. Chief among them is that the economic costs of climate action will be borne immediately and will be transparent to consumers, while the benefits of reducing emissions will be both uncertain and accrue for generations hence.

But climate action won’t just pay off in better weather in 2100. There are a range of co-benefits of policies that would reduce GHG emissions. Co-benefits, in this sense, are outcomes not directly targeted by the policy, such as reductions in non-targeted pollutants improving air quality and public health. When you bring these benefits into the equation, the case for climate action looks ironclad.

A study published in Nature Climate Change presents an analysis of three alternative policy scenarios for CO2 emissions from the power sector and compares them to a reference case that includes all planned air quality policies. The study demonstrates how reductions in CO2 will contribute to lower concentrations of PM2.5, a pollutant with well-documented health and environmental impacts, resulting in rapid and localized improvements in health-related outcomes.

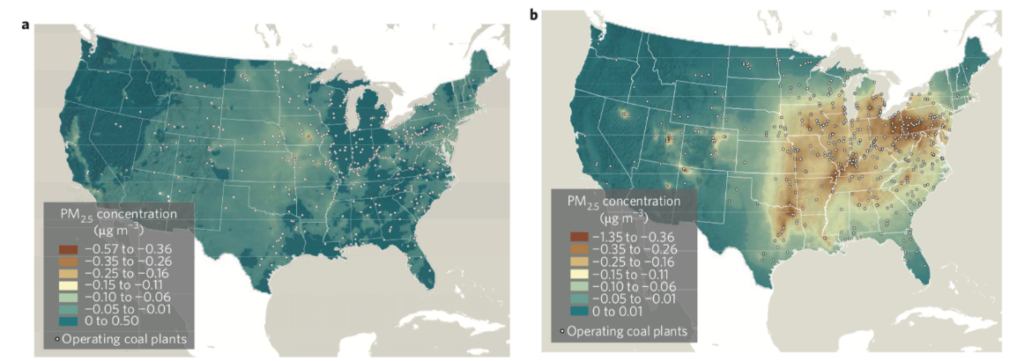

The study used a combined model of the energy system and air quality to evaluate how climate policies would influence air quality. The following figure shows the relative improvements in ambient concentrations of PM2.5 for a modest improvement in efficiency rates at coal plants (the policy being contemplated by the EPA as a replacement for the Clean Power Plan) and a more stringent intervention akin to the Clean Power Plan or a meaningful carbon tax.

Figure 1: Maps for the USA of the difference in annual average concentrations of PM2.5 in 2020 under modest climate policy (left) and more stringent policies (right) for the power sector.

Figure 1: Maps for the USA of the difference in annual average concentrations of PM2.5 in 2020 under modest climate policy (left) and more stringent policies (right) for the power sector.

In general, the modeling shows that more stringent climate policy results in greater co-benefits, but that the particular policy framework does matter. In comparing the co-benefits from their Clean Power Plan case and a carbon tax (levied at $42 per ton), the study finds that carbon pricing policy option results in significantly more reductions in metric tons of CO2 per year for a similar degree of co-benefits. The authors chalk the difference up to increased use of coal with CCS and less investment in energy efficiency under a carbon tax.

The lack of investment in demand-side energy efficiency and the expansion of coal due to CCS systems are fairly large assumptions, especially when considering recent LCOE analysis comparing alternative energy technologies to traditional fossil fuel technologies. The LCOE of alternative technologies has fallen to the point where full lifecycle costs of building and operating renewables-based projects have dropped below the operational costs aloe of conventional coal technologies, which will lead to a significant deployment of alternative energy capacity. Carbon pricing does not deter investment in demand-side energy efficiency mechanisms and would certainly correct market failures that keep the price of coal artificially low.

Although monetizing the health co-benefits brought on by these policies goes beyond the scope of this paper, the authors do mention that they expect the monetary benefits of avoided premature deaths to exceed the cost of compliance for either the Clean Power Plan or a meaningful carbon tax. Understanding that the monetary value of the co-benefits will outweigh the compliance cost of the policies should make it more attractive to the public as well as policymakers.

There is no doubt that the global nature of climate change presents a unique problem that makes it all the more challenging to enact sensible climate policy. It is often argued that costs of mitigation are felt domestically while the benefits accrue globally, a perfectly global “free-rider” problem. Thus, efforts to emphasize the localized and immediate benefits of combating climate change are essential in order to spur public support and political will for enacting climate policy, and highlighting the co-benefits of these policies will only bolster the argument for deep reductions in CO2 emissions.