The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) contains a well-known marriage penalty, and it may be about to get significantly worse. Marriage penalties in the tax code arise when the combined value of tax credits and deductions for two single individuals arbitrarily drops when those same individuals marry and file taxes jointly. The EITC is a refundable credit for lower-income workers, so the marriage penalty in the program is particularly concerning given the growing educational and class divide in U.S. marriage rates.

Congressional Democrats’ reconciliation package proposes to make permanent the American Rescue Plan’s temporary expansion to the EITC for childless workers. This includes roughly tripling the maximum value of this credit while extending eligibility to adults aged 19 to 24. While these are both worthwhile reforms in the abstract, the expansion is poorly designed. It more than doubles the EITC’s marriage penalty for childless workers, giving eligible couples a compelling reason to avoid tying the knot. Under the proposal, getting married could result in EITC recipients losing access to nearly $2,500 in tax credits per year, which in some cases represents more than 10 percent of an eligible household’s annual income.

There is good reason to believe these incentives will register with couples. The research on marriage penalties more broadly shows that they really can influence behavior. There is no reason to think EITC recipients are any less savvy about these matters, particularly given that their reported earnings are well known to “bunch” around the levels that maximize their refund.

Failing to fix this problem would not only be bad policy, but bad politics as well. Last week, a group of 35 Republican senators issued a letter to Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) and Finance Committee Chairman Ron Wyden (D-OR) decrying the penalties. The EITC has long been celebrated as a bipartisan success story. With that reputation already beginning to slip in recent years, Democrats should take their Republican colleagues’ concerns seriously, or risk further alienating conservatives from the program and causing the EITC to lose its bipartisan credentials altogether. Action is particularly compelling because there are relatively easy fixes available.

The reconciliation bill substantially increases marriage penalties for low wage workers

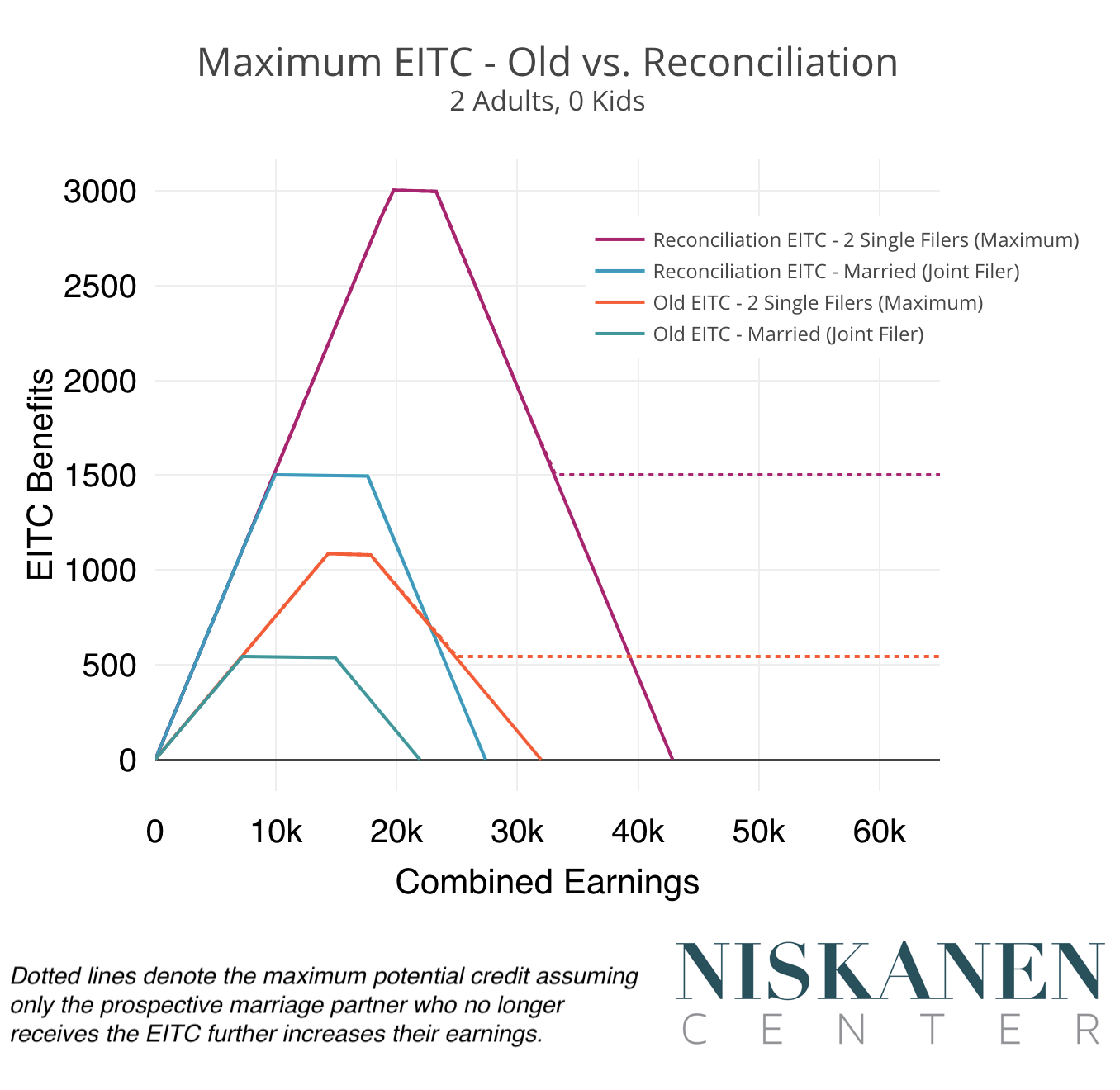

The chart below illustrates the maximum potential EITC benefit for two childless adults when they are single and when they are married for both the previous EITC structure and for the reconciliation proposal. The difference in height between the maximum EITC for married and single households indicates the size of the marriage penalty between the old childless EITC (orange vs. green) and what the reconciliation package proposes (purple vs. blue). In addition to being more severe, the marriage penalty in new EITC has broader eligibility by age and covers a wider earnings range, implying that a larger segment of working families would be affected.

The dotted line corresponds to the maximum potential credit for couples in which only one individual is eligible for the EITC. This scenario arises when one partner has earnings outside the EITC’s eligibility range while the other partner has earnings at the credit’s maximum value. For example, if someone with $50,000 in earnings marries someone with $15,000 in earnings, the latter partner’s $1,500 childless EITC is completely wiped out. The overall marriage bias of the tax code for dominant-earner households tends to switch from “penalty” to “bonus” at higher incomes, suggesting many of these households may still be better off than had they remained single. Nonetheless, among dual-earner households, extremely dominant-earner scenarios are relatively uncommon as a result of income-assortative marriages.

The chart below illustrates the maximum loss in EITC benefits that two childless working adults would face at a given level of combined income under the reconciliation proposal. Marriage penalties are most severe when both workers have roughly equal earnings. For example, two childless workers who each make $11,000 ($22,000 combined) would receive around $800 from the EITC if they were married, in contrast to the roughly $3,000 in combined EITC benefits they would be eligible for if they remained single and filed separately.

The EITC’s marriage penalty is much more explicit than in programs such as Medicaid. Medicaid recipients can lose eligibility following marriage if their combined incomes surpass the program’s cut-off, but for those who stay eligible, total benefits remain the same. In contrast, the maximum EITC benefit for a married couple is at least half that of two singles across most of the eligibility range.

The EITC’s marriage penalty derives from the decision to optimize the credit for incomes just below the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM) threshold, which includes transfer income in its poverty estimates. While the SPM poverty threshold for a one-adult household is roughly $11,000, adding a second adult raises this threshold by only about $6,000. Congress designed the EITC to maximize its superficial impact on poverty reduction with the least amount of spending necessary, clawing back benefits as soon as a family rises above an otherwise arbitrary poverty line.

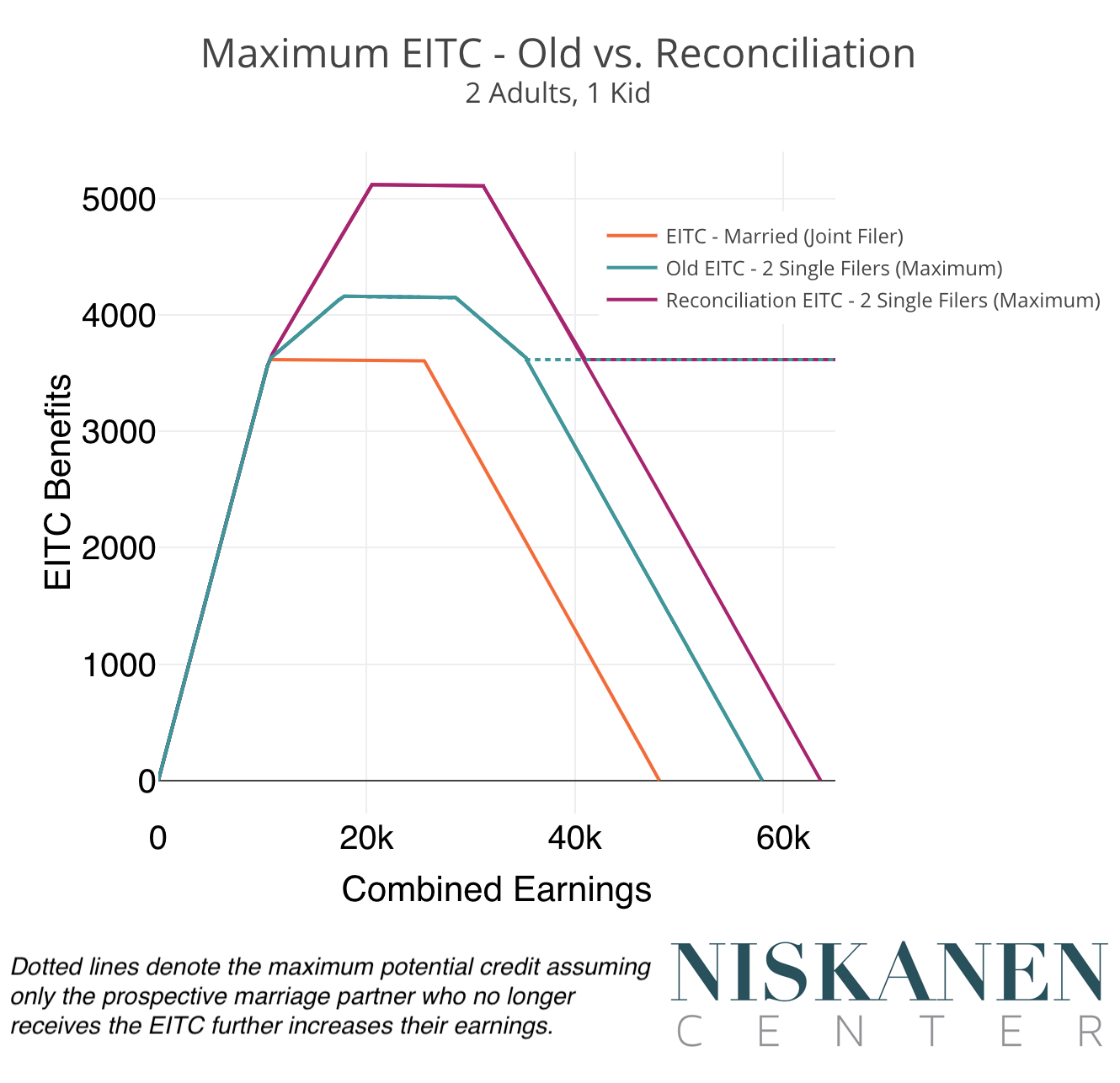

Marriage penalties for households with children

The proposed changes to the childless EITC threaten to substantially increase the breadth and depth of marriage penalties for families with children as well. Among unmarried parents who are both eligible for the EITC, one may claim the larger EITC for households with children while the other claims the childless credit. The biggest hit will come to families in which each parent separately claims the full value of their respective EITC. This is represented by the height difference between the purple and orange lines in the chart below. Such a scenario may even be somewhat common, as the EITC was originally designed to target maximum benefits to single parents in the context of the 1996 welfare reform. With the last two decades seeing rising rates of cohabitation, more households may be in this situation than policymakers assume.

The expanded EITC’s most severe marriage penalties will thus be felt by low-income single parents — predominantly single mothers — who decide to marry their partner. It seems unlikely that Democratic lawmakers intend to create a program that pays working-class single mothers and their partners to not get married, yet that’s effectively what the EITC reform in the reconciliation package would do.

How to get rid of marriage penalties

The changes to the EITC may have made sense as part of an emergency response to the pandemic. However, the credit’s design deserves a serious rethinking before being extended or made permanent. The challenge with marriage penalties is that fixing them without harming existing recipients often requires greater program funding. This is all the more reason to avoid making existing marriage penalties worse, as doing so would make any future fix that aims to keep existing recipients whole significantly more expensive.

Married couples who file taxes separately are currently barred from claiming the EITC. The easiest way to eliminate the EITC’s marriage penalty would be to change that rule. While there are other benefits to filing jointly, this would at least provide households with the option of choosing the filing method that minimizes the marriage penalty based on their particular circumstances. The next-best alternative would be to double the phase-out threshold for joint filers.

Earlier this year, Senator Mitt Romney (R-UT) released the most serious legislative proposal aimed at fixing the EITC’s marriage penalties to date. Like the reconciliation proposal, the legislation would increase the childless EITC but in a way that brings it into alignment with the EITC for households with children. Delinking the size of the EITC from the number of children in a household, while rolling the EITC’s per-child value into a child allowance, has the effect of greatly reducing potential marriage penalties. Democrats should follow Romney’s lead. The reconciliation package also contains an enlarged, fully refundable Child Tax Credit that would help offset any changes to the EITC’s generosity for households with children, making this Congress’ best opportunity in a generation to eliminate the EITC’s marriage penalty once and for all.

Samuel Hammond is the director of poverty and welfare policy at the Niskanen Center. Robert Orr is a Niskanen Center welfare policy analyst. Together, they are the authors of The Conservative Case for a Child Allowance.