“The Permanent Problem” is an ongoing series of essay about the challenges of capitalist mass affluence as well as the solutions to them. You can access the full collection here, or subscribe to brinklindsey.substack.com to get them straight to your inbox.

In the several years leading up to the launching of this essay series, I spent a great deal of time reading and stewing about our current difficulties and trying to place them in some analytically coherent big picture. One of the books I happened upon that made a big impression on me was Joseph Tainter’s The Collapse of Complex Societies. Interestingly, what I took away wasn’t the sense that we’re vulnerable to catastrophe – I had that already. On the contrary, reading that book opened my eyes to what I now think is the most promising path toward reviving and rejuvenating our ailing complex society.

Tainter, an anthropologist and historian at Utah State, published his slender volume in 1988, and it still stands as the leading text on one of the great riddles of history: why civilizations decline and fall. (Here’s a New York Times profile from a few years back.) Tainter’s work contrasts sharply with the 20th century’s most famous efforts to solve that riddle: Oswald Spengler’s The Decline of the West and Arnold Toynbee’s mammoth A Study of History, grandiose mashups of erudition, personal prejudice, and metaphysical speculation that won their authors celebrity and widespread acclaim as seers and prophets. The Collapse of Complex Societies, on the other hand, is unassuming and no-nonsense – and remains all but unknown outside scholarly circles. It starts with a survey of various historical episodes of collapse, ranging from famous examples like Rome and the Maya to obscure ones like the Chacoans and the Hohokam from what is now the southwestern United States. Next it briskly marches through the many contending explanations of collapse on offer and finds them all wanting to a greater or lesser degree. (On Spengler and Toynbee, Tainter is subdued but unsparing, concluding that “it seems almost unsporting to treat [them] so severely.”) The book then offers its own synthesis, applies it to the case studies provided earlier, and offers thoughts on how it might relate to the present as well.

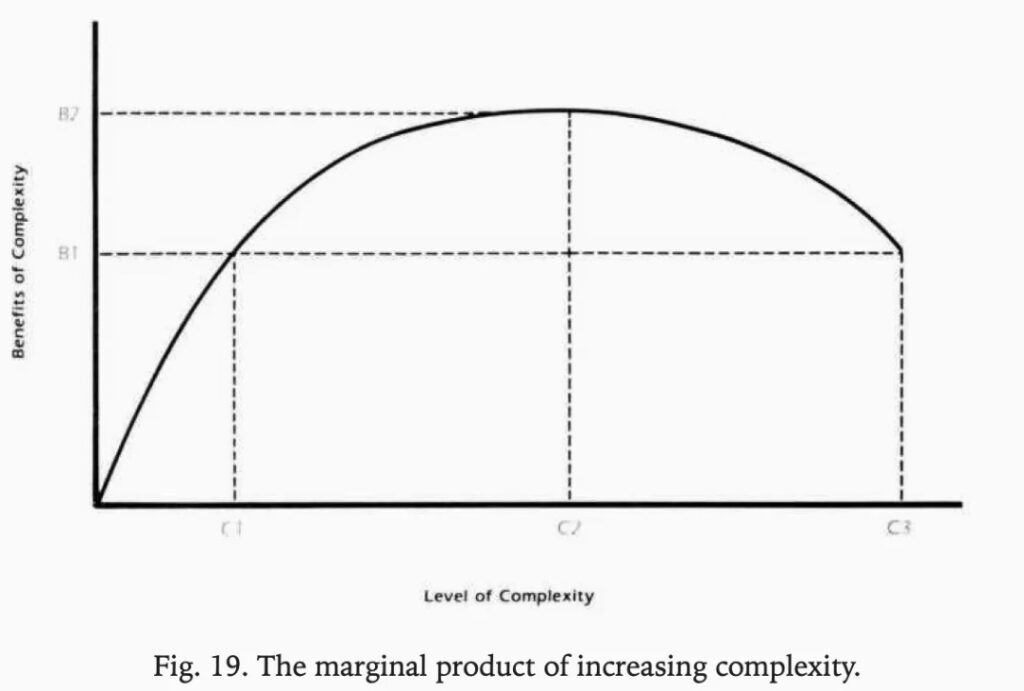

Tainter’s theory can be summed up concisely. Human societies are best understood as problem-solving organizations (with the problems being some combination of serving the narrow interests of elites and attending to the broader interests of society). More complex forms of social organization – including greater specialization, more intensive organization, and increased levels of hierarchy – arise to solve problems that can’t be managed otherwise. Investment in sociopolitical complexity pays off, creating larger and richer polities, but it also comes with costs that tend to mount over time. Eventually, as the costs of maintaining the status quo creep upward, further investment in additional complexity starts to yield diminishing returns (in the chart below, see the space between C1, B1 and C2, B2). Push things further, and returns turn negative (see the space between C2, B2 and C3, B1).

In Tainter’s analysis, it is declining marginal returns to investments in complexity that create societal vulnerability: The polity is now top-heavy, saddled with increasingly onerous overhead costs. The resulting decline need not be precipitous, though. An unusually favorable turn in the climate, a better than average ruler, internal problems for a hostile neighbor – such things could make for a temporary revival. On the other hand, a nasty negative shock could send things into a sudden tailspin. Sooner or later, the combination of heightened vulnerability and a potent challenge leads to one of two outcomes: loss of territory to a rival civilization; or, in the absence of any adversary in a position to fill the vacuum, collapse and reversion to a simpler, more decentralized social order.

Tainter’s simple model of the changing marginal returns of social complexity offers a convincing picture of civilizations’ entire life cycle – their rise and expansion as well as their decline and fall. As civilizations grow and expand, their social orders become more complex – a more extensive division of labor over a larger territory, a growing administrative and military apparatus, an enlarged and enriched elite class. During the expansion phase, rising complexity is self-reinforcing: new conquests bring new sources of plundered wealth and tax income, which fund a larger army, which enables more conquests. Eventually, though, expansion has to cease, whether because it bumps up against powerful rivals or because the distance from the governing center is just too great. Once expansion ceases, however, returns to complexity eventually reverse their course and start heading downward. After the one-off gains from plunder have been exhausted, it’s necessary to raise taxes on the provinces to maintain revenues and pay for a now-much-larger elite. But squeezing the provinces hurts production, which necessitates further tax hikes, which provoke dissent that requires the dispatching of additional occupying troops to quell, which necessitates further tax hikes, and so on. If the empire is in a crowded neighborhood, it may find itself shrinking as more vital neighbors now expand. If there is no competitor in a position to fill the vacuum, decline may accelerate to collapse: a return to a much simpler, more decentralized social order to shed the now-unbearable costs of complexity.

In the dynamic sketched out above, a lot of the work is being done by premodern conditions. The extent of territorial expansion is constrained by communications and transportation technologies, and the means of acquiring new wealth to stay ahead of the rising costs of complexity are largely limited to conquest and plunder. So the question naturally arises: Is Tainter’s model of rise and fall applicable to the contemporary world?

Tainter describes human societies as “problem-solving organizations” whose “sociopolitical systems require energy for their maintenance.” When those systems start to yield diminishing returns, the clock can be reset if a new “energy subsidy” can be found. In the premodern world, the main sources of energy were human and animal power, and thus the new subsidy could only be procured by territorial expansion (you could also luck into a new subsidy if an extended period of peace, good weather, and no major disease outbreaks produce sustained domestic population growth).

In the industrial era, new forms of energy subsidy became available: steam power and fossil fuels in the narrow sense, and modern technological and economic growth more broadly. These new literal and figurative power sources boosted human welfare dramatically, and they did so by enabling a dramatic complexification of the social order: rapid population growth, a huge increase in specialization and occupational variety, and the steady growth of a mass managerial and professional elite. I wrote a book a decade ago about this rise in social complexity – but my focus was on the implications for inequality, not whether complexity was ultimately self-undermining. In particular, I homed in on what the economist Frank Knight called the “encephalization” of economic life. Just as animals capable of more complex behaviors tend to feature higher ratios of brain to body size, so do more complex societies feature relatively larger “brains” – i.e., the managers, professionals, and entrepreneurs who conduct the “knowledge work” of the society. In the United States, for example, the share of the workforce accounted for by managers and professionals has risen from around 10 percent in 1900 to roughly 35 percent today. Meanwhile, the percentage of total social resources devoted to governance, as opposed to production, has climbed to a substantial fraction of total output in all the advanced economies. Our social order is thus growing increasingly top-heavy.

Has that top-heaviness reached the point that it’s problematic? Have we entered Tainter’s danger zone of declining marginal returns? Tainter devotes extensive discussion to the widespread presence of diminishing returns in modern life, paying particular attention to falling returns to R&D (discussed at length in this series here, here, and here) and both the growth of, and growing sclerosis within, government and bureaucracy more broadly (for my takes, see here, here, and here). But of course, as Tainter realizes, diminishing returns with respect to specific inputs are a ubiquitous fact of economic life; ongoing innovation, however, continually forestalls the arrival of zero or negative overall returns, thus keeping stagnation or economic decline at bay.

Looking through Tainter’s lens to assess our vulnerability to calamity, then, leads us to the question – already addressed at length in this series – of whether economic growth will eventually grind to a halt. In assessing that possibility, Tainter correctly identifies the most plausible possible mechanisms for an end to growth – namely, continued decline in R&D productivity and blowback from resource depletion or environmental harms.

He adds the further observation that contemporary conditions create a barrier to societal collapse that did not exist in the past. Specifically, the world today is “full” – that is, its entire habitable surface is now covered by states governing complex societies. The condition that made isolated collapse possible – namely, geographical isolation from other complex societies – is no longer present. If social order starts to dissolve somewhere now, we can expect the intervention of other states to prevent full-on collapse. Furthermore, because states are now all surrounded by peer competitors, conditions that in the past might have prompted dissolution are more likely to be borne because of the fear of being absorbed by another power. “No longer may any individual nation collapse,” Tainter concludes. “World civilization will collapse as a whole.” (I’m not sure this last point is entirely correct. I can picture catastrophes that end global communications and travel and leave some regions severely depopulated; in those areas, social existence could revert back to much simpler forms.)

In addressing the possibility of a sudden breakdown of contemporary social order, Tainter more or less confirms the analysis I’ve presented in this series. As I’ve put it, capitalism is currently suffering from chronic, degenerative conditions – namely, faltering dynamism and inclusion combined with increasingly dysfunctional politics. At the same time, it is vulnerable to a variety of different traumatic shocks. Put one or more of those shocks in the mix along with a gradual worsening of those chronic ills, and a rapid, calamitous unwinding of social complexity has to be admitted as a possible outcome.

But this wasn’t my big takeaway from Tainter. It’s when you step back from the specific question of susceptibility to collapse and look at the broader implications of his model that, in my view at least, things really start to get interesting. Specifically, Tainter’s model incorporates the following basic insights: (1) Social complexity is costly; (2) while social complexity can bring great benefits, it can also go too far and impose costs out of proportion to those benefits; (3) in the face of excessive costs of complexity, the equilibrating move is to unwind complexity and shed costs.

Those insights, it struck me, have applicability beyond the critical but narrow question of civilizational collapse. Although the risk of catastrophe cannot be dismissed, surely the more likely threat we face is chronic but stable dysfunction: no bang, just the long whimper of a social order mismatched with human needs and humane values. And if you look at the various chronic ills our social system is facing, you can see a common through line – namely, arrangements that work well to accomplish some core task or serve the interests of some core group, but which are overextended and failing in their broader responsibilities. If that’s right, if our various societal shortcomings reflect a common underlying problem, then perhaps there is a common approach to addressing those shortcomings. Tainter’s model points the way: The solution to overextension is retrenchment. Not collapse, of course, a cure unimaginably worse than the disease, but a controlled unwinding of excess complexity and rebuilding along simpler lines.

OK, let me spend the rest of this essay unpacking that last paragraph. I’ll start with the overall assessment of capitalism I offered in the initial essay in this series: “When its primary task was reducing material deprivation, capitalism rose to the occasion. But since its primary task shifted to facilitating mass flourishing — to living ‘wisely and agreeably and well — it has faltered.” In other words, there’s a sense in which capitalism has been overextended, repurposed with the expectation that it can provide not just material plenty but spiritual plenty as well – and it’s struggling in its new mission.

Struggling, but not failing abjectly. After all, contemporary postindustrial capitalism features a mass elite of entrepreneurs, managers, and professionals. Comprising some 20 to 30 percent of the population, this is the largest elite, both in absolute numbers and in size relative to society as a whole, that any social order in human history has yet produced, and – making due allowance for all the problems that bedevil life at the top today – its members are flourishing at a level that would stagger the imagination of aristocracies past. Thus, capitalism as a system for producing mass flourishing is overextended: It works for the top quarter or so of society, but not so well for everybody else.

One fundamental reason for capitalism’s difficulties in promoting more widespread flourishing is the steadily diminishing nexus between economic growth and well-being. It’s not true that more money above a certain threshold has no effect on happiness: The most recent examination of this issue found that reported happiness, both in terms of positive affect and overall life satisfaction, continues to rise indefinitely. Importantly, though, happiness doesn’t increase in linear fashion as income rises; rather, it increases in linear fashion with every doubling of income. And the increase is puny: a 0.1 standard deviation rise with every doubling. In the big picture, these tiny effects tend to wash out. If you look at the United States as a whole, there’s no connection between growth and happiness: According to one recent study, average happiness in the United States did not rise at all between 1972 and 2006, during which time real GDP per capita doubled.

The observation that money and things are not the most important components of a well-lived life hardly needs elaborate social scientific confirmation: It has been the consensus of sages and religious leaders throughout history. Of course, when more money permits the satisfaction of basic material needs, the connection to improved well-being is robust. Beyond that point, though, the impact of increased commercial consumption grows more ambiguous. The dose always makes the poison, so when more money allows overconsumption (of fattening foods, say, or anxiety-provoking social media) it can prove toxic. Also, chasing more money can be effective at improving happiness at the individual level because of the higher status it brings; at the national level, however, status races are zero-sum and cannot improve overall well-being.

When we look at what is increasingly missing from people’s lives today – namely, the strong, vital connections to family, friends, and community that are foundational to human flourishing – we see evidence of capitalism’s overextension there as well. Social dysfunction via atomization is to a large extent a product of de-functionalization: As the state and the market gradually assume functions previously served by personal relationships, those personal bonds inevitably loosen for lack of a raison d’être. Children once were economic assets on the farm and caretakers in old age; now they are one extremely expensive consumption choice among many less demanding others. Marriages were once unions of two producers; now they bring together people with common consumption patterns. The social welfare services once provided by fraternal organizations and churches are now the responsibility of the state. And the entertainment provided by spending time with friends is now giving way to the solitary pleasures of screen time.

Capitalism is overextended today, not just with respect to inclusion and well-being, but with respect to dynamism as well. With the achievement of mass material plenty, the continued mobilization of the population into wage employment and consumerist consumption has produced social and cultural conditions increasingly hostile to ongoing technological progress: growing loss aversion and safetyism, plus the proliferation of veto points from which any change that threatens somebody’s comfortable status quo can be thwarted; even more broadly, the general reorientation of society away from solving problems in the physical world and the increasing preoccupation with questions of personal identity and relative social status. Meanwhile, the R&D that drives progress forward has grown progressively bureaucratized by its dependence on huge national and international pools of public funding. As a result, researchers spend more and more time on administrative paperwork and less and less time actually advancing the frontiers of knowledge – with steadily declining returns on that funding as a result.

Joseph Tainter’s notion of “declining marginal returns to investments in complexity” is so abstract as to defy rigorous quantification, but in qualitative terms my impression is that it well captures the broad outlines of our current predicament. Our social order feels bloated and stagnant, its institutions extended beyond their prime use cases and flagging accordingly.

But now let’s turn Tainter’s model around. Instead of using it to look for signs of incipient collapse, let’s use it to investigate possible strategies for civilizational renewal. Here, the key is found in Tainter’s insight that collapse – the unwinding of complex social structures and reversion to simpler, smaller-scale arrangements – is the mechanism by which unsustainable costs of complexity are shed.

Collapse, of course, suggests something unplanned, sudden, and violent. And indeed, in the past the process of collapse was usually traumatic. Before a new equilibrium could be reached at smaller scale, armed conflict, disease, disruption of trade flows, the abandonment of cities, and mass migrations were the brutal means by which population would fall into line with the reduced productive capacity of a more decentralized order.

With our immense wealth and technological sophistication, however, we need not face such dreadful prospects. Instead of stumbling blindly toward the cliff, we can engage in a controlled, gradual, and partial process of social simplification and decentralization.

In other words, we can make the central problem we face the author of its own solution. Capitalism is struggling because it has raised expectations it can’t meet for most people. And it’s frustrating expectations precisely because of its phenomenal productivity, which, by freeing technological progress from dependence on large contributions of manual and clerical labor, has consigned ordinary workers to marginal economic importance and social status. But if high productivity is the culprit here, it can also be the way out. Since most people aren’t flourishing within the confines of the system, we need to redirect some of our resources and innovative capacity toward helping people achieve greater social and economic independence from the system. We need to reorient the pursuit of happiness so that more of it occurs without reliance on the market or the state.

I’ll have much more to say about all this in my next essay – in particular, on how breakthrough technologies now visible on the horizon can help us shed the excesses of social complexity and reclaim those habits of the mind and heart on which flourishing depends.

Photo Credit: iStock