“The Permanent Problem” is an ongoing series of essay about the challenges of capitalist mass affluence as well as the solutions to them. You can access the full collection here, or subscribe to brinklindsey.substack.com to get them straight to your inbox.

In my last essay, I argued that the progress of capitalist development from industrial to postindustrial has worked to marginalize the socioeconomic position of ordinary people. Steadily declining dependence on their contributions in the most progressive sectors of the economy means that what they have to offer is less important than in the past; the result has been a drop in status and a loss of collective social power. This development, I believe, is the fundamental driver of our new class divide.

Here I want to describe a similar dynamic concerning the political marginalization of ordinary people. (By the way, I’m using “ordinary workers” and “ordinary people” in lieu of the off-putting “less-skilled workers” and “less-educated voters.”) In the new politics created by the conditions of mass affluence – namely, a postindustrial economy, mass higher education, an enormous increase in the scope and complexity of governance, and the ongoing revolution in communications and mass media – the participation and representation of ordinary people in the political process has declined, as has attention to their economic interests. Consequently, politics now exacerbates more than mitigates the crisis of inclusion, as the rules of the game for many important sectors of the economy have been rewritten to favor the elite at the expense of everybody else.

It’s weird in retrospect, but when Steve Teles and I were writing The Captured Economy we gave almost no thought to the historical process that had created the situation we were describing. We noted that in the past the redistributive effects of regulatory policies went in all different directions, whereas the regulatory interventions of recent decades virtually all redistributed up the socioeconomic scale. And we gave political-science-y reasons for how regulatory capture can happen and how elite insiders have special advantages. But we didn’t even try to explain why the pattern of redistributive effects had shifted. When the book came out and we started giving talks, though, that question came up pretty much every time. We fumbled around, mentioned the decline of unions, but didn’t have much to say. I’ve been thinking about it a lot since then.

And it turns out that something I had written years earlier pointed me in the right direction, even though back then I didn’t connect all the dots. In The Age of Abundance, I told the story of how the advent of mass affluence after World War II triggered convulsive change in culture and values – a “postmaterialist” and “postmodern” shift, employing the terminology used by political scientist Ronald Inglehart, from “survival” values centered on acquisition and material security to “self-expression” values centered on quality of life and self-realization. This cultural sea change naturally carried over into politics as well, with the conflict between old values and new emerging as a major axis of political contestation during the tumultuous 1960s.

I’ll quote a bit from the book:

In the new era, the interests of the white working classes no longer seemed a pressing concern. Factory workers, far from oppressed, were now enjoying middle-class incomes and moving to the suburbs…. And so, as the sixties dawned, twentieth-century liberalism’s fundamental passion – to use the agencies of the state in support of social equality – redirected its ardor to needier and more appealing objects….

[T]he triumph over scarcity shifted the primary focus of liberal egalitarianism from lack of material resources to lack of cultural acceptance. When most people were poor, and many desperately so, the great invidious distinction was between the haves and the have-nots, and liberals cast their lot with the latter. But with the arrival of widespread prosperity, liberal sympathies were redirected to the grievances of “belong-nots” – various groups of dissidents and outsiders that challenged or were excluded from America’s cultural mainstream. Thus the increased attention to discrimination against blacks and women, harsh treatment of suspects and criminals, the problems of American Indians and migrant workers, and restraints on free speech and cultural expression….

Fear that domestic inequalities were being replicated on the world stage fed the growing discomfort with American “imperialism” and its real and imagined depredations against the yellow, brown, and black peoples of the Third World. And, without stretching overly much, the embrace of environmentalism could be seen as a call for better treatment of an excluded “other” – in this case, the natural world.

The upshot of all this was that liberal policies and priorities lost touch with, and indeed grew increasingly antagonistic toward, the culture and values of the vast bulk of the American population – the constituency that as a result of this conflict came to be known as the Silent Majority or Middle America.

This political transformation may have started in the United States, but it soon spread to other rich democracies. And the new values that were upending culture and politics may have made their dramatic debut on college campuses, but they soon became the norm throughout the more highly educated strata of society – a group that was rapidly expanding as the new information economy was in the process of creating a mass elite of managers and professionals.

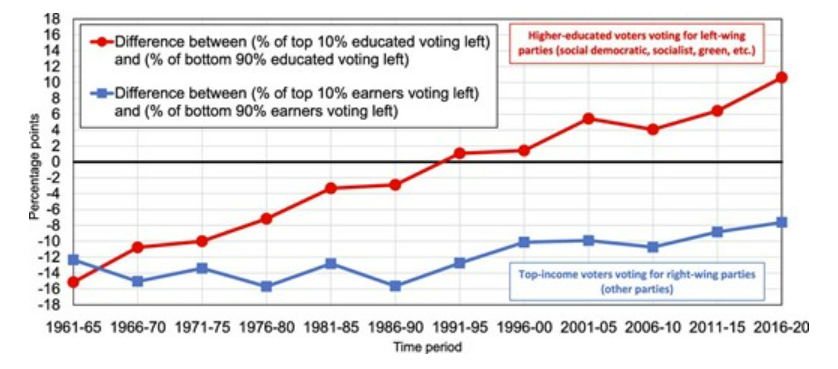

As described by the French economist Thomas Piketty and colleagues, the rich democracies transitioned from class-based politics, where the primary conflict was between the wealthy elite and everybody else, to a “multi-elite” politics. In the new politics, a “merchant right” that was affluent and more culturally conservative squared off against a “Brahmin left” that was highly educated and more culturally progressive. Now there were two main fault lines in politics: one based on income, the other based on education. As you can see in this chart based on the experience of 12 rich democracies, polarization between left and right based on income has generally held firm (although in the U.S. it has weakened considerably in recent election cycles), while divergence along educational lines – a proxy for differences in cultural values – has widened steadily over time.

The shift from class-war to culture-war politics resulted in a significant downgrading of the priority accorded to the economic interests of ordinary people. There was now a major cross-cutting source of political conflict to sow division among different working-class constituencies and prevent their uniting in a common front on behalf of their shared pocketbook concerns. And liberal elites, who once sympathized wholeheartedly with the working class, now increasingly saw the white working class as the enemy of social progress; growing liberal contempt for blue-collar backwardness was matched by growing blue-collar contempt for liberal permissiveness and self-righteousness.

If the crackup of class-based politics could be captured in a single moment, one candidate would be the New York City “Hard Hat Riot” of 1970. On May 8, just a few days after the Kent State shootings, hundreds of construction workers and office workers attacked a large group of student protesters, leading to hours of mayhem and around a hundred people injured. Just weeks later, Richard Nixon invited the construction worker leaders to the White House and received a hard hat as a souvenir.

And so the postwar social-democratic coalition to uplift the material conditions of ordinary people ruptured on the jagged edges of rapid cultural change. By the 1980s, when it became clear that inequality was once again on the rise and the salience of class conflict reasserted itself, the political realignment into a New Left and New Right was too well established to be reversed. Humpty Dumpty remains a shattered wreck to this day.

The marginalization of ordinary workers’ interests in the wake of ideological realignment was exacerbated by the professionalization of political life that was occurring simultaneously. Here again, we are looking at the consequences of mass affluence. As capitalism developed, its operations grew ever more complex – and thus required an ever larger elite of managers and professionals to direct and coordinate that complexity. It’s a development that the economist Frank Knight referred to as the “cephalization” of economic life. Just as animals capable of more complex behaviors have relatively larger brains, so economies with increasingly extensive and intricate divisions of labor have relatively larger elites of “knowledge workers.”

The process of cephalization necessarily spilled over into government: As the economy grew more complex, the task of governance became more complex as well. With the dramatic growth in the size and scale of government came a corresponding growth in bureaucracy – not just large numbers of clerks whose simple information-processing jobs would eventually be automated, but also mid- and upper-level civil servants with highly specialized and technical expertise. Politics professionalized as well, as seeking and holding elective office – traditionally a part-time job except at the very highest levels – became a full-time career. Congress didn’t stay in session over much of the year until the 1960s; election campaigns in the past were mercifully brief and correspondingly cheap. Year-round government and the rise of never-ending campaigning created a whole new industry of office seekers, pollsters, and consultants. As politics became more professionalized, it naturally grew more individualized as well – and the role of political parties as the directors of political life went into long-term decline.

More broadly, civic and associational life generally became more professionalized. As observed by, among others, Robert Putnam and Theda Skocpol, the whole structure of American civic engagement was transformed: from large, democratically organized mass membership organizations with active local chapters to a profusion of new business associations, nonprofits supported by charitable foundations, and national advocacy groups with large professional staffs whose “members” exhausted their responsibilities by writing checks. This change in civic life was a response, not only to the growing complexity of government and the need for deep professional expertise to be in a position to influence it, but also to plummeting communications costs that made it possible to form and maintain organizations without the need to root them in local meetings of the rank and file. In the altered ecosystem of postindustrial civic and political life, the numerous and nimble new professionalized groups simply outcompeted the old mass-membership organizations and drove them from their former prominence.

The end result of all this change is that politics is now largely a game for well-educated elites: there are few paths to power and influence that don’t start with at least a four-year university degree. The change in the demographics of political actors can be seen across the rich democracies, but the example of the United Kingdom is especially vivid. Back in 1964, roughly 35 percent of Labour Party members of Parliament came from working class occupational backgrounds; by 2010, that figure had fallen to 10 percent.

Something I learned from co-writing The Captured Economy is that when a political process is dominated by actors from a certain narrow group, the results of the process tend to get skewed to conform to that group’s outlook and interests. And that’s what has happened to politics in the rich democracies. It’s not just a matter of this or that industry being captured by narrow group interests, although that’s certainly going on as well. Rather, the entire political system has been captured by highly educated managerial and professional elites and is now run according to their narrow and well-insulated points of view.

This capture has been especially fateful because it occurred at the same time that elites were diverging culturally from the rest of the country. The cultural shift from materialist “survival” values to postmaterialist “self-expression” values has been most widespread and far-reaching among the highly educated. Accordingly, the gap between the political class and the citizenry is not just financial and educational; there is also a yawning gap in deeply and passionately held beliefs about good and bad, right and wrong. Although elites on the political right tend to be more culturally conservative, and certainly act that way in public, nevertheless they are generally much more socially liberal than the people they represent. And elites on the left regularly find themselves drawn to positions – just recently, “defund the police,” “abolish ICE,” and uncritical support for gender affirming surgery for minors – that are vehemently rejected by overwhelming majorities.

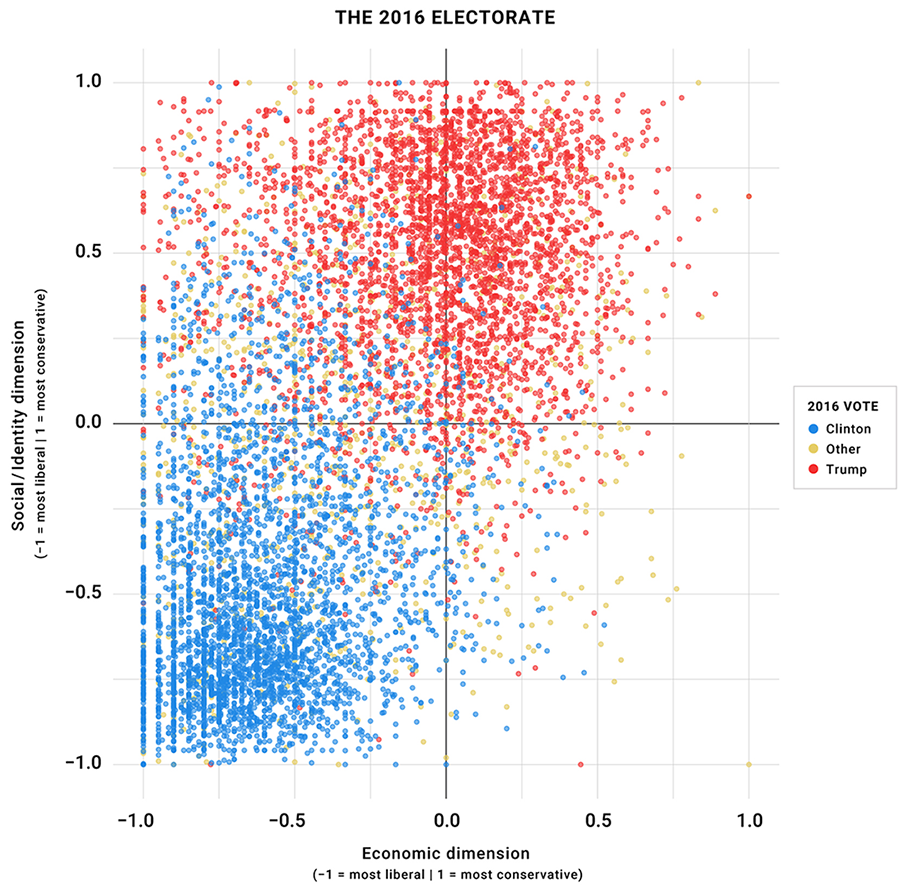

The cultural distance between elites and ordinary voters has often worked to narrow the apparent range of political debate, as elites on both sides collaborate to keep some issues off the table. But this suppression of non-elite views builds up pressure and seething resentment over time – and if that built-up pressure can find an outlet, the results can be ugly. Consider this much-discussed map of the 2016 American electorate prepared by Lee Drutman and the Voter Study Group:

The traditional bases of the two parties lie in the lower-left and upper-right quadrants: solidly liberal and conservative, respectfully, on both economic and cultural issues. Many elites of both left and right, meanwhile, describe themselves – at least among themselves – as socially liberal and fiscally conservative, and thus find themselves in the comparatively empty lower-right quadrant. And diametrically opposed to them are large numbers of people in the suppressed quadrant of the economically liberal and socially conservative – a sizeable group of people with views that long went without any representation in national debate. This is the vacuum that authoritarian populism has rushed to fill. Donald Trump was the first U.S. presidential candidate to claim these voters as his own. Of course he offered them poisonous demagoguery, not actual concern for their outlook and interests, but he made them feel seen, and that was enough to enable him to nearly wreck American democracy. Whether he will ultimately succeed remains an open question.

Similar dynamics are playing out in Europe. The emergence of more culturally oriented politics could be seen in the rising prominence of far-right parties in the 1970s and the birth and rapid growth of Green parties around the same time. As mass immigration, and especially Muslim immigration, became a cultural flash point, and as the social-democratic parties made their neoliberal turn in the 80s and 90s, a large bloc of economically progressive, culturally conservative voters came to feel unrepresented by the established parties of center-right and center-left. Hence two signal developments in 21st century European politics: the growing electoral clout of the authoritarian populist far right, and the collapse of the social-democratic parties that once were the voice of a unified working class.

The elite capture of politics has done more than roil cultural conflict to the point of imperiling democratic stability. It has also worked to seriously aggravate the socioeconomic marginalization of ordinary people I described in my previous essay. First of all, elites’ elevation of culture-war politics has split working-class constituencies that might otherwise have united on behalf of their bread-and-butter interests. Although most people’s absorption in cultural conflict is completely sincere, the fact remains that this absorption gives the rich and powerful a crucial political advantage: it allows them to divide and conquer.

And it’s not just that democratic politics has become a less effective brake on economic elites’ pursuit of self-interest. It’s that politics now frequently turbocharges their self-dealing. The result is the “captured economy” that Steve Teles and I wrote about – key sectors of economic life where public policy has been systematically skewed to funnel income and wealth up the socioeconomic scale while undermining the dynamism upon which our common prosperity depends. In finance, intellectual property, the regulation of the legal and medical professions, and legal restrictions on land use, upward redistribution is occurring on a massive scale, while the competition necessary for well-functioning markets is either badly distorted or actively throttled.

Even when elites aren’t purposefully twisting the rules in their favor, the whole professionalized style of governance tends to produce policymaking environments that are hostile to non-elite interests and participation. Professionalization is a product of complexity; it is the job of professionals to master and navigate the complexities of contemporary social life. This characteristic virtue of the professional, the ability to handle complexity, leads to the professional’s characteristic vice: a strong inclination to make things more complicated than they need to be. Using impenetrable jargon whose decoding requires professional assistance, designing procedures so baroque that professional guidance is needed at every step – this kind of thing is virtually second nature among any group of people whose economic value consists of knowing things that most people don’t.

Needless complexity is ubiquitous in contemporary government – from tortuous applications for government benefits, to the use of multifactor balancing tests in lieu of simple rules, to all the interagency working groups needed to make government run because authority over a particular subject is routinely shared among many different agencies. In the United States, the professionalization of government has been dominated by lawyers, so Rube-Goldbergism is especially rampant. Compare the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 to the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010: the former totally remade the U.S. financial industry in 37 pages, while the latter pursued its more modest goals through 848 pages of statute and thousands of pages of implementing regulations. We can take this as a representative indicator of the general trend – a trend that makes participation in the business of government intimidating and off-putting to all those uninitiated in its secret codes and handshakes.

When the inherent complexity of modern governance is magnified many times by gratuitous embellishments, the result is a policy environment with nearly ideal conditions for capture by elite insiders. It is no accident that the regulation of finance and intellectual property, two policy areas notorious for their byzantine complexity, is so rife with rent-seeking and regressive redistribution. The spectacular misallocations of people and money accomplished by zoning and other land-use restrictions would not have been possible without the hyperlocal system of decision-making that ensures virtually all affected interests are never in the room where it happens. And as law professor Nicholas Bagley has argued here (and at greater length here), the “procedure fetish” that is endemic in American administrative law, although motivated by a desire to make government more responsive to broad public input, actually greatly empowers the rich and powerful to protect their interests at the expense of effective government. We have inadvertently created an unaccountable and imperious “vetocracy” that hamstrings the operations of government at every turn – with the frequent result of shielding vested interests from disruption or even inconvenience.

There’s a great deal of Green Lantern theorizing when it comes to prospects for reversing the yawning class divide. If the trend toward the marginalization of ordinary people seems so resistant to redirection, it must be because bad people are being bad too hard and good people aren’t being good hard enough. There’s comfort in believing that passion and willpower are all that’s needed to change the world, but it’s false comfort. The disconcerting fact is that the arrival of mass affluence – the greatest humanitarian blessing of all time – has caused both the economic system and the political system to downgrade the importance of ordinary people’s contributions and interests. Archimedes taught us that with the right lever you can move the world. But where now can ordinary people find the leverage they need?