One of the sleeper issues of the election season now getting underway is a federal job guarantee (JG). Such a policy would offer public-service employment (PSE) to anyone who wanted it, with government at some level or an approved nonprofit organization as the employer.

A job guarantee is far from a new idea. During the Great Depression, the federal government created thousands of jobs through programs like the Works Progress Administration and Civilian Conservation Corps. In his 1944 State of the Union address, President Franklin Roosevelt put the right to a job at a living wage at the very top of his “Second Bill of Rights.” However, since 1978, when a job guarantee was dropped from the final draft of the Humphrey-Hawkins Full Employment Act, calls for a broad job guarantee have largely been confined to the political fringes.

Now the idea is undergoing a revival. Several Democratic presidential hopefuls have endorsed it in one form or another. Sen. Bernie Sanders has endorsed a full-scale job guarantee. Sen. Cory Booker introduced legislation in the last Congress that called for JG pilot programs in 15 cities. Not to be left behind, Sens. Elizabeth Warren, Kirsten Gillibrand, and Kamala Harris signed on as co-sponsors. The Green New Deal, introduced in both the Senate and the House with more than 100 co-sponsors, calls explicitly for a job guarantee along with its better-known measures to combat climate change.

But why is a job guarantee being revived now, when unemployment is at a 50-year low? In reply, JG proponents point to three gaps that they see as persisting even in today’s tight labor market:

- The hidden unemployment gap: A gap between the number of people counted in the labor force and the number who would seek work if jobs were available at a higher wage.

- The pay gap: A difference between what people are now paid and the maximum that their employers would be willing to pay if necessary.

- The public service gap: A large, unmet need for labor-intensive public services that would generate benefits equal to or greater than the cost of providing them.

In this two-part series, I will argue that this three-gap model of the labor market raises more questions than it answers regarding the merits of a federal job guarantee. Part 1 focuses on the hidden unemployment gap, looking at the number and characteristics of people who would be likely to sign up for public-service jobs. Part 2 will look at how the pay gap and public service gap affect the potential costs and benefits of a job guarantee. (Readers who would like to see a simple graphical version of the three-gap model are invited to view this slideshow.)

Two proposals

Proposals for a job guarantee vary in their degree of detail. The following discussion will focus on two of the most fully developed plans. One is outlined by Mark Paul, William Darity Jr., and Darrick Hamilton (PDH) in a report commissioned by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. The other comes from L. Randall Wray, Flavia Dantas, Scott Fullwiler, Pavlina R. Tcherneva, and Stephanie A. Kelton of the Levy Economics Institute.

The two proposals have much in common. Both propose to offer a full- or part-time job to anyone over the age of 16 (Levy Institute) or 18 (PDH) who wants one. The federal government would cover the full cost, but in most cases, it would not be the actual employer.

In the PDH plan, most jobs would be with state and local governments, with provisions for direct federal employment as a backup. The Levy Institute plan envisions jobs with state and local governments and with nonprofit organizations. Both proposals specify a generous package of benefits, including health insurance, child care, retirement, parental leave, and so on. Both call for a living wage — that is, a wage high enough to ensure that one earner can support a family at an income above the poverty level. Under the PDH plan, the wage would vary with experience and qualifications. In the Levy Institute version, all participants would receive the same wage.

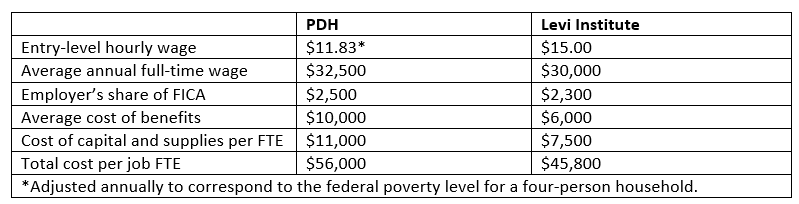

The following table gives estimated costs per job for the two plans:

Estimating uptake for a JG program

The number of applicants for guaranteed jobs would depend on the size of the hidden unemployment gap — the difference between the number of people now working and the number who would take a guaranteed job if it were offered. Here are the Levy Institute’s estimates, based on data for the third quarter of 2017, at which time the official unemployment rate was 4.1 percent:

- 4.8 million to 6.1 million workers from the officially unemployed — that is, those who are not working but actively looking for work. The higher of those numbers includes all of the unemployed except those who are on temporary layoff, while the lower figure excludes everyone who has been unemployed for less than five weeks.

- 4.8 million to 5.7 million people from those currently out of the labor force but who say they would like a job.

- And 3 million to 6 million people who would like to work full-time but are currently working part-time either because they cannot find full-time work or because of child care responsibilities.

The total comes to around 12.6 to 17.8 million people, or about 8 to 11 percent of a labor force of 160 million.

Using 2018, the PDH provides a somewhat lower estimated uptake of 10.7 million people. Most of the difference is attributable to some 3.5 million people who say they want a job but have not looked for work in the previous 12 months, and are thus not classified by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) as “marginally attached to the labor force.” The Levy Institute counts them as likely candidates for PSE, but the PDH does not. In practice, there seems to be little difference between the willingness to work of this group and those who have looked for work in recent months. One analysis of labor market transition data, for instance, notes that people who want a job but have not looked within the past year are almost as likely to find employment in any given month as are those who are officially “marginally attached.” If both groups are included, there is little difference between the uptake rates expected by the PDH and the Levy Institute.

For the sake of discussion, let’s accept some number in the range of 12 million to 18 million as the number of people likely to apply if guaranteed public-service jobs were offered to all who wanted them. That is not the whole story, however. If we want to evaluate JG as anti-poverty policy, we need to look more carefully at the characteristics of likely applicants, not just at their numbers.

Nonemployment and financial stress

There is no question that many people who want to work but can’t find a job suffer serious financial stress, but that is not true for all of them. Consider, for example, the results of a survey of the nonemployed conducted in 2014 by the Kaiser Family Foundation, the New York Times, and CBS News. That survey focused on the 13 percent of the prime-age population (25 to 54 years old) who were not working but said they wanted a job. Most of the estimated uptake for both the PDH and Levy Institute versions of a job guarantee would come from that group. Here are some key findings of the survey:

- Among all nonemployed prime-age individuals, 36 percent said their employment situation was not a source of stress and 20 percent said it was only a minor source of stress.

- Among those who said they were nonemployed but able to work, 26 percent self-identified as homemakers. Among self-identified homemakers, 77 percent said their nonemployment was not a source of stress and another 15 percent said it was only a minor source of stress.

- Among all prime-age nonemployed adults, 51 percent reported they were very or somewhat financially secure. Among self-identified homemakers in this group, 76 percent reported they were very or somewhat financially secure.

The nonemployed, nonstressed people in this survey were prime-age adults whose financial needs, in most cases, were presumably being met by the earnings of other members of their households. The survey would not have included teenage or college-aged people living at home but looking for part-time work while studying. Nor would it have included older people who wanted part- or full-time work to supplement an already minimally adequate retirement income, or simply to get out of the house and do something interesting.

It is likely, then, that at least some guaranteed jobs would be taken up by people who were motivated by a desire for self-fulfillment or extra pocket money rather than a need to escape poverty. Providing those jobs would increase the cost of a JG program and, at the same time, would dilute its rationale as an antipoverty measure. Additional surveys or results of JG pilot programs might shed light on the number of people in each category. Meanwhile, the reported survey suggests that the issue is far from trivial.

The hard-to-employ

The long-term unemployed and those who want to work but have given up looking are key target categories for JG policy. Those categories, by their nature, include many people who are, for one reason or another, hard to employ.

Both the CPBB and Levy Institute proposals recognize that the workers they seek to attract are more likely to have less education and lower skills than the average employed worker. Both recommend that their programs include at least a modest training component. However, there is more to employability than education and training. The hard-to-employ also include people with criminal records, unstable housing, substance abuse issues, family situations that interfere with regular work schedules, borderline mental and physical conditions that fall short of actual disability, and other problems that make it hard to hold a job.

Studies of past and present employment programs show that such people can benefit from work opportunities outside the normal labor market. However, they also suggest reasons for caution. Consider, for example, the results of a set of social-enterprise experiments in California, as reported by Mathematica Policy Research. Social enterprises are mission-driven, nonprofit businesses that are specifically established to hire the hard-to-employ. The social enterprises included in the Mathematica study offered work in service positions similar to those envisioned for JG beneficiaries.

An important takeaway from the Mathematica report is that participants required extensive support services to achieve success. Those support services included not only job-related training (as recognized by JG advocates), but also general training in job-readiness and personal finance skills; assistance with clothing, transportation, and housing; food pantries; nutritional education; counseling to avoid relapse into drug dependency or criminal behaviors; education regarding public benefits; and tax preparation.

Another takeaway is that even with extensive support services, the employment gains to the hard-to-employ, although statistically significant, were quantitatively modest. After one year of entering the program, the rate of employment among participants rose from 18 percent to 51 percent; the number in stable housing rose from 15 percent to 53 percent; and the share of income from government fell from 71 percent to 24 percent. To put it concisely, at best half of the participants actually achieved the goal of self-sufficiency.

Similar findings emerge from studies of work requirements, a way of moving people from welfare to work that uses a stick rather than a carrot. The gold standard for evaluating the effects of work requirements is a set of 11 controlled experiments known as the National Evaluation of Welfare-to-Work Strategies (NEWWS) that were conducted in the 1990s as part of the welfare reforms of that time. The experiments each lasted five years and were conducted in various cities around the country. Each experiment compared a group of people whose benefits were conditioned on work requirements with a control group who continued to receive welfare as usual.

Some of the NEWWS experiments did produce modest gains in employment. Importantly, though, they did so only where they were backed by intensive administrative support, adequate funding, and well-trained staff. Case workers and other administrators had to do more than simply monitor eligibility and compliance. In the most successful experiment (Portland), case workers interacted one-on-one with participants to cajole them into jobs or training programs, or to coerce them to make greater efforts by threatening withdrawal of benefits. Experiments in cities like Oklahoma City and Detroit, where staffing and administrative funding were lower, reported no statistically significant increase in employment.

The authors of the PDH and Levy Institute plans recognize that some applicants may have difficulty adjusting to the JG program. However, rather than looking to supportive case work for such employees, they emphasize discharge or discipline. For example, in a reply to critics, L. Randall Wray, a key member of the Levy Institute team, writes:

The JG should not devolve to either workfare or welfare … Workers can be fired for cause — with grievance procedures established to protect their rights, and with conditions on rehiring into the program.

Similarly, the PDH report says:

For employees to receive their compensation, they must show up to their job and perform the tasks assigned to them. As was the case with the WPA, a Division of Progress Investigation (DPI) should be established to monitor shirking or corruption. If workers are found to be negligent, or generally disruptive to the workplace, disciplinary action can be taken by the DPI.

All things considered, neither of the JG proposals considered here pay enough attention to the potential challenges posed by the hard-to-employ. Either these plans should budget substantial additional amounts for administrative support and one-on-one case work, or they should cut back their expectations for the number of people that their programs will succeed in moving from poverty to self-sufficiency.

Guaranteed jobs vs. nonmarket production

Finally, JG advocates need to give more attention to the fact that many potential applicants are already working, but not in the market economy. Both the PDH and Levy Institute teams point to an increase in GDP as one of the benefits of a JG program. However, to the extent such a program simply replaced nonmarket production with market-based production of similar goods and services, changes in measured GDP would overstate those benefits.

Caregiving is perhaps the most obvious example of a service that is already being produced, but not for pay, by JG candidates. BLS data tell us that many of the people who are out of the labor force but want a job say they are unavailable for paid employment because they are caregivers for children or other family members. The same is true of many who are working part-time but say they would prefer full-time jobs.

Consider, for example, two parents, in two separate households, who have each been staying home to care for two young children. If a JG program spent $56,000 to hire one of them to work in a community arts program and hired the other as a day care worker to look after all four children, measured GDP would rise by $112,000. However, the only new services produced are those of the arts program. The day care services were already being produced by the parents themselves, but were not counted in GDP, since they were outside the market economy.

Additional examples can be found in the vast volunteer sector of the U.S. economy. A BLS report on volunteering found that as of 2015, more than 62 million people aged 16 and older participated in volunteer work. Of those, 5.9 percent devoted more than 500 hours a year to volunteering — a huge amount of work. Much of that was spent on exactly the kind of jobs that would be offered by JG programs. In some cases, people who are now out of the labor force and who volunteer as wildlife monitors would happily take paid jobs as JG wildlife monitors. In other cases, people who are already employed but volunteer to pick up trash in the local park on weekends would find they are no longer needed, since a JG worker is already doing the job. Either way, at least part of the work done by JG participants would displace something already being done by volunteers.

Conclusions

JG advocates are right when they say that the official unemployment rate, recently at a 50-year low, understates the degree of slack in the labor market. However, an abundance of potential applicants is not enough to conclude that guaranteed public-service employment would be a cost-effective way to move people from poverty to self-sufficiency. To make a convincing case, JG advocates need to pay more attention to three characteristics of the nonemployed and underemployed population they hope to attract:

- Not all of the nonemployed and underemployed suffer financial stress. Many live comfortably on the earnings of other family members, on savings, or on other resources.

- In practice, many people who are not working but say they want a job have problems that make them hard to employ, such as unstable housing, substance abuse, criminal records, and mental health conditions that fall short of full disability.

- Some potential participants in a JG program are already working, but outside the market economy.

These issues alone are enough to rethink the costs and benefits of a full-scale federal job guarantee. In Part 2 of this series, we turn to additional questions about the cost-effectiveness and practicality of guaranteed jobs.