Offshore wind energy can fundamentally alter clean energy production in the U.S. and significantly increase our ability to meet deep decarbonization goals. Offshore wind resources in the U.S. could produce more than 7,200 terawatt hours of generation per year, which is considerably more than the country’s current electricity use–especially in areas where onshore wind and solar potential are small, such as the Northeast.

Like other renewable generation technologies, offshore wind has seen precipitous cost reductions in recent years. The U.S. offshore wind industry is poised for significant growth over the next decade, and with it will come thousands of new jobs and billions of dollars in revenue. A new study published by Wood Mackenzie (WM) last week found that 28 gigawatts of offshore wind development could generate $1.7 billion in federal revenues from lease sales in two years and $166 billion in private capital expenditures by 2035. It also found that it could support roughly 80,000 full-time equivalent jobs per year from 2025 to 2035.

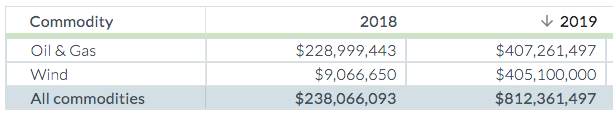

To put this potential lease revenue into context, the most recent Interior Department offshore wind lease auction brought in more than $400 million, smashing the previous record of nearly $42.5 million. The chart below compares offshore wind lease sale revenue and oil & gas lease sale revenue across the U.S.

In the past two fiscal years, oil & gas lease sale revenue totaled a little over $630 million. That is about 40 percent of the potential for offshore wind for the next two years. According to the WM study, the northeast coast of the U.S. would make up $1.1 billion of the total revenue. California could generate $515 million, and the Carolinas would generate the remaining $60 million.

Despite the economic promise of this technology, the offshore wind industry faces political and regulatory risks that could jeopardize its growth. A major regulatory impediment to the development of U.S. offshore wind resources is the Jones Act, which requires that any components moved between American ports be transported using U.S.-flagged vessels. The nascency of the offshore wind industry in the U.S. means only a small number of the specialized ships used to construct offshore wind farms operate under the U.S. flag, and foreign platforms are forbidden to operate between U.S. ports by the Jones Act. Instead, companies have to use foreign vessels supplied by U.S. flagged support ships.

This regulatory barrier increases the costs by 50 percent more per KWh for U.S. offshore wind developers relative to developers in European countries. Despite the promising economic trends of the offshore wind industry, the Jones Act is creating conditions whereby U.S. wind developers are unable to use specialized foreign vessels, and are paying more than they have to construct offshore wind projects. The threat of tariffs also looms over the industry. Two weeks ago, the U.S. International Trade Commission issued a statement finding that U.S. manufacturers were being “materially injured” by the import of utility-scale wind towers from Canada, Vietnam, Korea, and Indonesia. This decision will likely lead to tariffs, which will push up costs and hurt U.S. developers.

The timely growth of U.S. offshore wind production will deliver clean energy to the U.S. and generate a significant amount of near-term and long-term economic benefits. If the lease sale revenues of offshore wind projects are any indication of how large of an industry this could be, then addressing political and regulatory barriers is necessary for the U.S. to reap the benefits of this promising commodity.

Photo by Pixabay on Pexels