This piece is part of a larger series on how immigration can help relieve U.S. labor shortages. You can explore the full series here.

Introduction

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, labor shortages have become a highly visible part of American daily life. Restaurants and shops post “Help Wanted” placards alongside notices of reduced hours or interrupted services due to employee shortages. Shipping delays cause frustration among online shoppers, and “due to unforeseen circumstances” has begun to feel trite and universal.

Immigration can play a key role in addressing America’s labor shortages, and while it’s ultimately up to Congress to reform the system, the Department of Labor can act today to improve the availability of foreign talent, even in the absence of legislative action, simply by updating Schedule A, a list that designates positions that employers are finding particularly difficult to fill.

While the list has not been updated in over 30 years, updating Schedule A to help America’s current labor shortages could provide crucial relief to American industries stifled by a devastating worker crisis and could alleviate the administrative burdens and delays facing both the federal government and petitioning employers.

History of Schedule A and current policy

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 passed with broad bipartisan support and created elements of the labor certification process that are still in place today.[1]

The law allows the U.S. to offer permanent visas to “qualified immigrants who are capable of performing specified skilled or unskilled labor, not of a temporary or seasonal nature, for which a shortage of employable and willing persons exists in the United States.”[2] Later in 1965, the Department of Labor (DoL) issued the rules that would determine if an occupation qualifies for the visa program on a case-by-case basis.[3] The regulation simultaneously established an expedited process to decrease administrative delays for certain workers who would be employed in pre-specified industries, including those listed under Schedule A.

Schedule A is a list of designated occupations for which DoL has declared there to be an insufficient number of workers in the U.S., and determined that the employment of immigrants would not adversely affect the wages and working conditions of similarly situated U.S.-based employees.[4]

Employers hiring for a Schedule A designated occupation can largely bypass the requirement to demonstrate that an exhaustive headhunt has failed to turn up a qualified employee domestically, saving them a minimum of six months.[5] All petitions — including Schedule A occupations — are still evaluated to ensure the positions and employees meet the original requirements of the program.[6] Employers struggling to fill vacancies not included in Schedule A utilize the typical labor certification process to demonstrate the need for foreign talent in roles that may not be captured by the national list.

In 1965, when Schedule A was first introduced, it included broad categories for advanced degree holders with at least two years of working experience, nurses, and bachelor’s degree holders in certain engineering and science fields.[7] The regulations also gave the Labor Secretary discretionary authority to amend this list “at any time, upon his own initiative,” and in the years that followed, multiple administrations actively used this authority to update the list to reflect market needs.[8]

In 1971, additional procedural requirements were added to the labor certification process, but the simplified process for occupations designated under Schedule A remained. At that time, the list included occupations in dietetics, medicine and surgery, nursing, pharmacy, physical therapy, and religious services.[9] Additional regulatory changes were implemented throughout the 1980s, and in 1991, the creation of preference groups for specific occupational categories within the employment-based visa process effectively eliminated several of the Schedule A designations by establishing separate procedures and requirements for those groups.[10] This 1991 adjustment marks the last meaningful revision of Schedule A. Today, only nurses, physical therapists, and immigrants of exceptional ability are on the Schedule A list.[11]

Labor shortages and the economy

While COVID-19 markedly exacerbated labor shortages and their visibility to consumers, the shortfall of workers has been building continuously over the past several years. From 2011 to 2021, the number of job openings has increased by an average of 12 percent per year, even accounting for the sharp downturn seen in early 2020.[12] Over the same time period, the working-age population in the U.S. increased by an average of just 0.3 percent per year.[13] Among other factors, this has led to a situation where the number of job openings regularly dwarfs the number of unemployed Americans. In August 2022, for example, about 6 million Americans were unemployed, yet job openings in the same month exceeded 10 million.[14] Even if every currently unemployed Americans’ qualifications, aspirations, and location perfectly aligned with the current job openings, over 4 million positions would still be vacant.

Unfortunately, there is often far more of a mismatch between the skills, interests, or localities of unemployed Americans and the needs of employers than the prior hypothetical would assume, and this mismatch has sweeping impacts on the American economy. This scarcity of labor plays a significant role in supply chain disruptions, and together, these constraints drive prices upward, contributing to the staggering inflation rates that Americans now face.[15] As of March 2022, inflation was on track to cost the average American household $5,200 in 2022, and inflation rates have risen since then.[16]

In July 2021, job openings were slightly lower than they are currently at 10.9 million, yet the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta estimated that the unavailability of suitable labor had still “reduced nominal private-sector gross output by roughly $738 billion, on an annualized basis.”[17] In particular, these labor shortages have an especially negative impact on small businesses.[18] Among surveyed small-business owners facing such hiring difficulties, an overwhelming 97 percent stated that the shortages have impacted their bottom line.[19] For small businesses battered by COVID-19’s original impacts, these ongoing challenges could lead to still greater hardship or even closure.[20]

Early pandemic layoffs initially drove unemployment, but the “Great Resignation” that followed has also played a role in the continued difficulties employers face in recruiting and retaining talent. As companies try to entice workers to join and stay in their ranks, wages have been increasing far more rapidly than prior to the pandemic.[21] Even in light of the increased compensation offers though, many industries still struggle to fill the jobs required to stay afloat.

The need for immigrants to help America’s labor shortages

Slowed rates of immigration compared to pre-pandemic trends have contributed to labor shortages and inflation, costing American families and employers billions.[22]

Even if the flow of incoming immigrants returns to pre-pandemic levels, though, the size of the immigrant worker population in the U.S. would still be significantly behind what it would have been without the pandemic.[23] For example, between fiscal years 2019 and 2020, admissions of temporary workers and their families dropped over 37 percent, and in 2021, dropped another 28 percent from that reduced level.[24] Lingering effects of field office closures, vaccine requirements, and ongoing backlogs continued to slow admission rates long after borders reopened.[25]

Though admissions have increased in 2022, they fail to compensate for the labor that would have been accessible to American employers had admissions of foreign nationals across all visa categories remained consistent.[26] This disparity contributes to the critical shortages facing American businesses as immigrants participate in the American workforce at higher rates than native-born workers, and they are disproportionately well represented in the industries most often deemed “essential.”[27]

As fierce as the competition currently is for domestic labor, American employers are also competing against one another to gain access to the limited, and often insufficient, allocation of employment-based visas.[28] For instance, for upcoming FY2023, over 48,000 employers across the United States submitted over 480,000 requests for specialty worker visas, yet given the cap on these visas, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) ultimately only invited about one-fourth of those to be adjudicated for even potential consideration.[29]

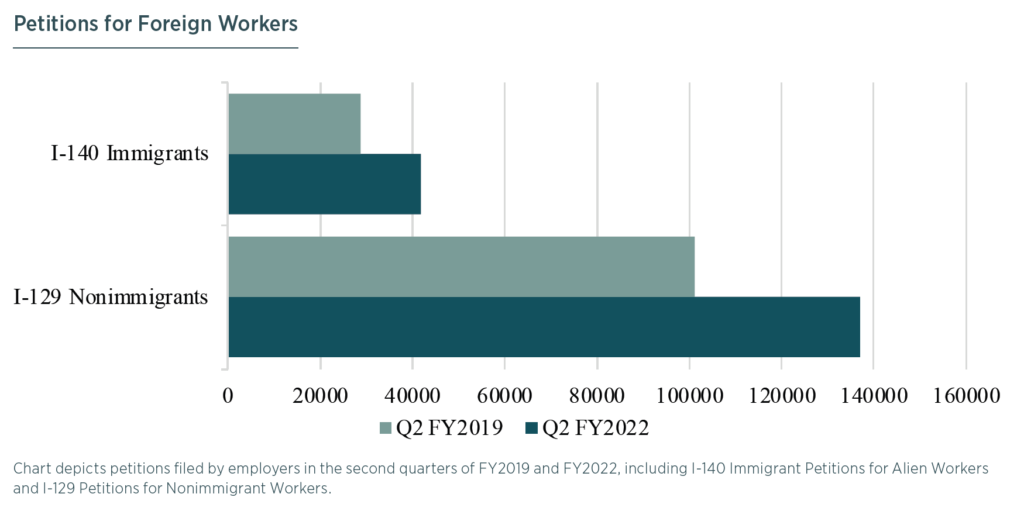

Comparing Q2 of FY2022 to Q2 of FY2019 prior to the pandemic, I-129 petitions for nonimmigrant (or temporary) workers are up nearly 36 percent, and I-140 petitions for immigrant (or permanent) workers are up approximately 46 percent.[30] While many of these petitions are still waiting to be adjudicated, the latest estimates also indicate that nearly 172,000 immigrant workers have already been approved and deemed as necessary to the American workforce, yet remain stuck in visa backlogs.[31]

Even withstanding the sizable backlog populations, the sharp increase in immigrant petitions comes at a time when lengthy USCIS processing times impede importing the talent the American economy so desperately needs. For example, in September 2022, the processing time for a Form I-140 Immigrant Petition for Alien Worker of the “skilled worker or professional” category was 17 months through the Nebraska Service Center.[32] As of September 2019, the processing time for the same category through the same service center was only 5 to 7 months.[33] Adding the cumbersome labor certification process outlined previously, the so-called “PERM” process can leave employers grappling for talent they need for many months or even years.

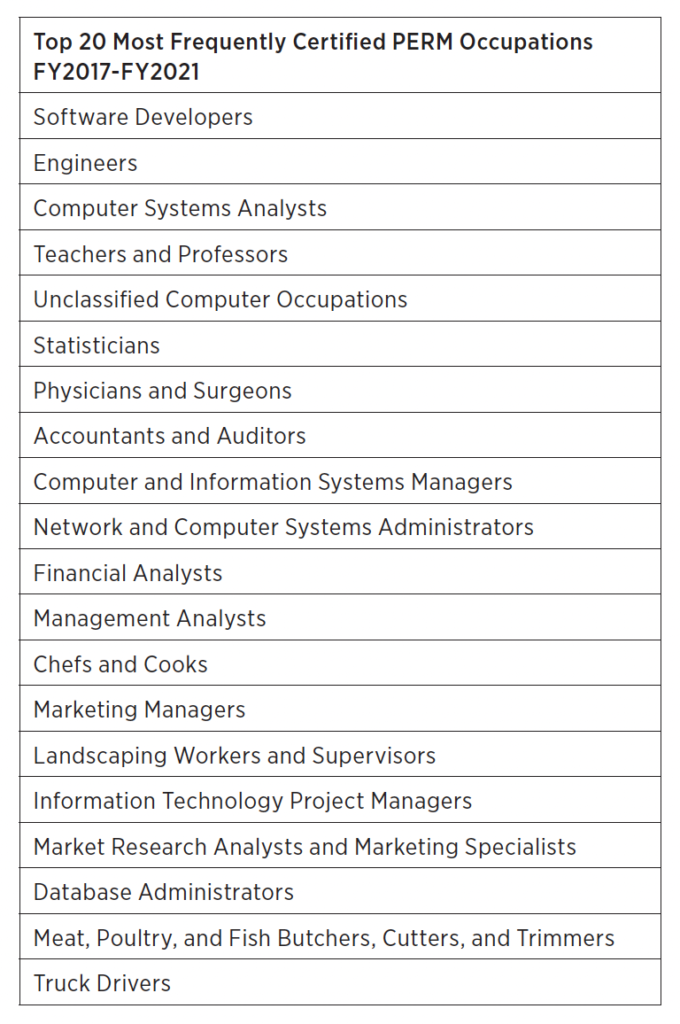

The table shown to the right reflects aggregated data from certified, or approved, permanent labor certification applications from the past five fiscal years.[34] Over the past five years, DoL has certified over 111,000 requests for software developers, underscoring the perpetual and severe need that American employers have for individuals qualified and willing to fulfill these roles. Other occupations among the most frequently certified include teachers and professors, physicians and surgeons, and financial analysts, among others.

Unsurprisingly, many of these occupations also appear on the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ list of the top 20 occupations with the most new jobs projected to be created over the next eight years, including cooks, truck drivers, market research analysts, management analysts, and others, signaling that the need for skilled labor could continue to grow exponentially.[35]

Not only do immigrants create more jobs than they take, but they are also filling crucial roles that fuel the maintenance and growth of the American economy and help ease labor shortages.[36] Below, additional information is provided for some of the industries reflected in the above list.

Physicians and surgeons

According to estimates published by the Association of American Medical Colleges, the current physician shortage is estimated to balloon to an overwhelming total of up to 124,000 within the next 12 years.[37] With rural areas already experiencing the negative effects of limited physician access, ensuring adequate staff availability must be a priority of public health policy.

From May 2019 to May 2021, median annual wages for general internists rose over 20 percent, yet the growing shortages in the medical field persist.[38] Representatives of the American Medical Association, Physicians for American Healthcare Access, and various medical recruiting firms have advocated for increased or improved utilization of immigration to fill these shortages.[39]

Truck drivers

The American Trucking Association estimated that the trucking industry was 80,000 drivers short of meeting freight demand in 2021.[40] While some may argue that improved compensation would help alleviate the shortages that have been growing in this industry since before the pandemic, delivery truck drivers’ median annual salary grew 24 percent faster than the overall median wage of all occupations from 2016 to 2021, yet the shortages remain.[41]

Immigrants are overrepresented in the truck driving profession, and while other measures, including automation and qualification relaxation, have been proposed or implemented, industry leaders have still repeatedly called upon government officials to improve the viability of immigration routes for these drivers.[42]

Teachers and professors

For the 2022-2023 school year, the Department of Education has identified over 1,800 teacher shortage areas, including shortages in every state.[43] Postsecondary education is also experiencing faster than average growth in job openings, and educators overall have experienced concerning levels of burnout and turnover since the pandemic began.[44] Teachers of immigrant origins have represented a growing share of the educational workforce in the past several years, and organizations from across the industry have repeatedly pushed for improved immigration policies.[45]

Conclusion

As demonstrated by DoL’s repeated certification of the U.S. labor market’s need for immigrants in these rapidly growing fields, immigrants are and will continue to be crucial to the growth and maintenance of vital U.S. industries. While much can and should be done to improve STEM education in the United States or to increase the matching potential between American skills and interests and current job openings, the statistics still show that this alone will likely not be enough.

Schedule A was designed to provide expedited relief to industries clamoring for labor that they are unable to find domestically, but the list’s stagnation has rendered it out-of-date and out-of-touch with the current labor market. The DoL should update Schedule A to reflect America’s current labor shortage needs and should consider the inclusion of occupations like those listed above that have already repeatedly passed through the labor certification process. This would ensure ongoing protection of the domestic American workforce by including only industries that comply with Schedule A’s regulatory requirements for shortage occupations in which immigrant employment would not adversely affect American workers. Simultaneously, U.S. employers, including the small businesses most affected by current labor shortages, would benefit by receiving expedited access to the labor that they so desperately need.

Updating Schedule A for America’s current labor shortage needs will not eliminate all backlogs and processing delays, but it is an important step that the executive branch can take to alleviate administrative burdens and wait times, improve damaging labor shortages, and support the continued recovery of the American economy through immigrant laborers.

[1] “Historical Highlights: Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965,” United States House of Representatives, October 3, 1965; “TO PASS H.R. 2580, THE AMENDED IMMIGRATION AND NATIONALITY ACT,” Govtrack, August 25, 1965.; “TO PASS H.R. 2580, IMMIGRATION AND NATIONALITY ACT AMENDMENTS,” Govtrack, September 22, 1965; “Immigration and Nationality Act,” United States Citizenship and Immigration Services.

[2] Pub. L. 89-236 (October 3, 1965).

[3] Office of the Secretary of Labor, “IMMIGRATION: AVAILABILITY OF, AND ADVERSE EFFECT UPON, AMERICAN WORKERS,” volume 30 Federal Register pg. 14979 (December 3, 1965).

[4] Ibid.

[5] “Prevailing Wage Determination Processing Times,” Department of Labor, August 31, 2022.

[6] Policy Manual: Volume 6, Part E, “Chapter 7 – Schedule A Designation Petitions,” U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

[7] Office of the Secretary of Labor, “IMMIGRATION,” 1965.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Office of the Secretary of Labor, “IMMIGRATION: IMMIGRANT LABOR CERTIFICATIONS,” volume 36 Federal Register pg. 2462 (February 4, 1971).

[10] Lindsay Milliken, “A Brief History of Schedule A: The United States’ Forgotten Shortage Occupation List,” The University of Chicago Law Review Online, September 22, 2020.

[11] U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, “Chapter 7 – Schedule A Designation Petitions.”

[12] Number of yearly job openings measured as an annual mean of monthly job openings; Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, 2011 – 2021 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics).

[13] “Population ages 15-64, total – United States,” (The World Bank, 2011 – 2021).

[14] The Employment Situation, August 2022, (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, September 2, 2022).; Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, August 2022 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, October 4, 2022).

[15] Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Monetary Policy Report – February 2022 (Federal Reserve, February 25, 2022); Tom Barkin, “Breaking Down the Labor Shortage,” Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, March 3, 2022.

[16] Andrew Husby and Anna Wong, “U.S. Households Face $5,200 Inflation Tax This Year,” Bloomberg Economics, March 29, 2022; “CPI for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U),” 2022 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics).

[17] Job Openings and Labor Turnover, July 2021 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, September 8, 2021); John Graham, et al. “Are Labor Shortages Slowing the Recovery? A View from the CFO Survey,” Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, July 14, 2021.

[18] Ibid.

[19] “Ahead of Largest Gathering of Small Business Owners in the U.S., New Goldman Sachs Survey Finds Small Businesses Facing Unprecedented Challenges,” Goldman Sachs, July 13, 2022.

[20] Leland D. Crane, et al. Business Exit During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Non-Traditional Measures in Historical Context, Finance and Economics Discussion Series, 2020-089r1 (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, April 2021).

[21] Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Monetary Policy Report.

[22] Tom Barkin, “Breaking Down the Labor Shortage.”; John Graham, et al., “Are Labor Shortages Slowing the Recovery?.”

[23] “Could Immigration Solve the US Worker Shortage?,” Goldman Sachs, May 31, 2022.

[24] Scott Meeks, U.S. Nonimmigrant Admissions: 2021, Annual Flow Report (Department of Homeland Security, July 2022).

[25] “USCIS Offices Preparing to Reopen on June 4,” U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, April 24, 2020.; “COVID-19 Vaccination Required for Immigration Medical Examinations,” U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, September 14, 2021.; “Visa Appointment Wait Times,” U.S. Department of State – Bureau of Consular Affairs.; “Reducing Processing Backlogs,” U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, March 2022.

[26] “Legal Immigration and Adjustment of Status Report Fiscal Year 2022, Quarter 2,” Department of Homeland Security, July 8, 2022.

[27] “Foreign-Born Workers: Labor Force Characteristics—2021,” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, May 18, 2021; “IMMIGRANTS AS ESSENTIAL WORKERS DURING COVID-19,” U.S. Government Publishing Office, September 23, 2020.

[28] “Number of unemployed persons per job opening, seasonally adjusted,” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, July 2022.

[29] “H-1B Electronic Registration Process,” U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

[30] “Number of Service-Wide Forms by Quarter, Form Status, and Processing Time January 1, 2022 – March 31, 2022,” U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services; “Number of Select Service-Wide Forms by Quarter and Form Status Fiscal Year 2019,” U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

[31] Annual Report of Immigrant Visa Applicants in the Family-sponsored and Employment-based preferences Registered at the National Visa Center as of November 1, 2021, U.S. Department of State.

[32] Check Case Processing Times, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

[33] Check Case Processing Times, Internet Archive: U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, September 4, 2019.

[34] Data excludes requests that were certified but then expired prior to utilization.; “Performance Data,” Historical Case Disclosure Data, PERM FY2017-FY2021, U.S. Department of Labor.

[35] “OCCUPATIONAL OUTLOOK HANDBOOK: Most New Jobs,” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, September 8, 2022.

[36] Jessica Love, “Immigrants to the U.S. Create More Jobs Than They Take,” KelloggInsight, October 5, 2020.

[37] Andis Robeznieks, “Doctor shortages are here—and they’ll get worse if we don’t act fast,” American Medical Association, April 13, 2022; Robert Orr, “The U.S. Has Much to Gain from More Doctors,” Niskanen Center, August 4, 2021.

[38] “OCCUPATIONAL OUTLOOK HANDBOOK: Physicians and Surgeons,” Internet Archive: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, July 31, 2020; “OCCUPATIONAL OUTLOOK HANDBOOK: Physicians and Surgeons,” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, May 2021.

[39] Andis Robeznieks, “Easing IMGs’ path to practice is a key to solving physician shortage,” American Medical Association, July 13, 2022; Andrew Kreighbaum, “Virus-Linked Doctor Shortage Has Physicians Demanding Visa Fixes,” Bloomberg Law, February 15, 2022; Mark Crawford, “Doctors from Abroad: A Cure for the Physician Shortage in America,” The Catholic Health Association of the United States, March-April 2014.

[40] “Supply Chain Watch,” American Trucking Associations

[41] Jack Kelly, “There Is a Massive Trucker Shortage Causing Supply Chain Disruptions and High Inflation,” Forbes, January 12, 2022; “OCCUPATIONAL OUTLOOK HANDBOOK: Delivery Truck Drivers and Driver/Sales Workers,” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, May 2021; “OCCUPATIONAL OUTLOOK HANDBOOK: Delivery Truck Drivers and Driver/Sales Workers,” Internet Archive: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, April 28, 2017.

[42] Rich Mendez, “CEO of major logistics firm makes a pitch to immigrants to address shortage of truck drivers,” CNBC, October 27, 2021; Caitlin O’Kane, “Program would allow certain teens to become truck drivers amid supply chain crisis,” CBS News, January 19, 2022; Ari Hawkins, “A Trucking Crisis Has the U.S. Looking for More Drivers Abroad,” Bloomberg, August 2, 2021.

[43] “Teacher Shortage Areas,” 2022-2023, U.S. Department of Education.

[44] “OCCUPATIONAL OUTLOOK HANDBOOK: Postsecondary Teachers,” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.; “The Power Moves to Retain Teachers Amid the Pandemic,” U.S. Department of Education, May 2022; GBAO, “Poll Results: Stress and Burnout Pose Threat of Educator Shortages,” National Education Association, January 31, 2022.

[45] Kelvin KC Seah, “Immigrant educators and students’ academic achievement,” Labour Economics: Volume 51 (April 2018): pgs. 152-169; Jeff Gross, Can Immigrant Professionals Help Reduce Teacher Shortages in the U.S.?, World Education Services, 2018.; Jessica Fregni, “The Push to Expand Access to Teacher Certification for DACAmented Educators,” Teach for America, December 16, 2021.