“The Permanent Problem” is an ongoing series of essay about the challenges of capitalist mass affluence as well as the solutions to them. You can access the full collection here, or subscribe to brinklindsey.substack.com to get them straight to your inbox.

We are able to say that communist central planning failed because we can compare its results with those of capitalism. We can look at nighttime photos of the Korean peninsula; we can contrast Soviet bread lines with the groaning shelves of an American supermarket.

Imagine a nearby Universe, though, where on Earth Prime, Marxist-Leninist revolution had somehow triumphed globally while reducing the most advanced countries to ruins. Rebuilding from the ashes would have felt like progress, as would the spread of industrialization on the preexisting pattern to previously agrarian societies. The regime would continue to fund science, scientists would continue to make discoveries, engineers would sometimes design new products based on those discoveries, and some of those new products would make it into the next five-year plan and be produced and distributed. Progress of some sort, then, would continue, and every increment of it would be credited to the productive power of socialism. All setbacks and disappointments, meanwhile, could be blamed on bad weather or the still-incomplete evolution from Homo sapiens to Homo sovieticus. No one would have any firm comparative basis for arguing that the system was irredeemably dysfunctional and that the world could be far, far richer under different institutions.

I have come to believe that we are in an analogous (though far less dire!) situation today. A revolution swept the world a half-century or so ago, and all of us today live under its sway. As a result, the world today may very well be much poorer than it otherwise could have been – and the existence and extent of that massive loss are all but invisible.

The revolution I’m talking about is most closely associated with environmentalism, but I think it’s critically important not to conflate the two. I regard good stewardship of the natural world to be a bedrock component of “living wisely and agreeably and well,” and humanity’s record on that score during industrialization was abysmal. Accordingly, the emergence of the modern environmental movement in the 1960s and 70s – the growing recognition of the grievous harms inflicted by industry on both the natural world and human health, and the firming resolve to do something about it – must be judged as a large and necessary step forward in human progress.

No, the revolution I’m talking about can be described as the anti-Promethean backlash – the broad-based cultural turn away from those forms of technological progress that extend and amplify human mastery over the physical world. The quest to build bigger, go farther and faster and higher, and harness ever greater sources of power was, if not abandoned, then greatly deprioritized in the United States and other rich democracies starting in the 1960s and 70s. We made it to the moon, and then stopped going. We pioneered commercial supersonic air travel, and then discontinued it. We developed nuclear power, and then stopped building new plants. There is really no precedent for this kind of abdication of powers in Western modernity; one historical parallel that comes to mind is the Ming dynasty’s abandonment of its expeditionary treasure fleet after the voyages of Zheng He.

It was primarily through environmentalism that the anti-Promethean backlash manifested itself and exerted influence over events, yet there is no fundamental, necessary connection between concern for the health and beauty of the natural world and antipathy toward – in Francis Bacon’s formulation, the use of science and technology “for the relief of man’s estate.” Indeed, as is now becoming clear in the context of climate change, it is only through the continued development of our technological powers that we can hope to arrest and reverse the immense damage we have caused.

Yet if the connection between environmentalism and the anti-Promethean backlash was theoretically contingent, in historical context it was eminently understandable that these two separate streams of thought met and merged. To see why, we need to understand why it was that the environmental movement emerged when it did. Industry had been loud and dirty from the beginning, and thus from early days had inspired romantic revulsion at its “dark satanic mills.” Why did it take until the 1960s for a mass environmental movement to emerge?

I believe that we can attribute the timing to the maturation of two deep social trends triggered by the spread of material plenty, and to the specific historical context in which those trends were building momentum. The first trend was the “postmaterialist, postmodern” cultural shift documented by Ronald Inglehart: As economic security spread throughout the populace, priorities shifted from physical security and material accumulation to self-expression and quality of life. With the confidence that hearth and home were safe and sound, people naturally turned their gaze to their broader surroundings and began to care more about the beauty and healthiness of those surroundings. Around the world, we see evidence for an “environmental Kuznets curve” in which industrialization leads first to worsening environmental degradation on all fronts but then, when a certain income per capita threshold is reached (something in the neighborhood of $10,000 a year), many environmental indicators begin to show improvement. We can think of environmental quality as a luxury good for which demand increases disproportionately as income rises.

The second trend, described in my last essay, was the growing power of loss aversion in step with the widening and deepening of affluence. As people acquired more, they had more to lose, and accordingly began worrying more about holding on to what they had. Greater attention to preserving our natural patrimony was one result; so was greater concern with environmental contaminants and their threats to human health. Worth mentioning again here is the economist Charles Jones’ paper on “Life and Growth”: If the ascribed value of human life rises faster than the value of consumption, the optimal rate of consumption growth may fall well behind what is technologically and organizationally feasible.

The rapid growth of the environmental movement in the 1960s can thus be understood as a consequence of the ripening of these two trends, a kind of Baptists-and-bootleggers alliance of cultural attitudes: on the one hand, the high-minded broadening of moral horizons and greater empathy for the non-human “other”; on the other, the self-regarding “I’ve got mine, Jack” stance that regards change as not worth the bother if it carries any possibility of loss.

Environmentalism, then, was a consequence of mass affluence. But its specific character was profoundly shaped by the fact that humanity’s achievement of mass affluence occurred against the backdrop of the 20th century’s parade of high-tech horrors: two world wars in which the industrial technologies of mass production were adapted to the cause of pitiless mass destruction; the Holocaust, in which atavistic savagery was carried out using the latest technologies and organizational techniques; and finally, the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the looming specter of civilization-ending nuclear annihilation. Those nightmarish events put an end to the heady, naïve faith in Progress with a capital P that had reigned during the 19th century, and among an influential swath of society they induced the equal and opposite error of anti-humanistic technological despair.

No doubt the heightened sense of technology’s dark side helped both to raise environmental awareness in the first place and then to infuse that awareness with anti-Promethean fervor. Because people had been bludgeoned repeatedly with other evidence of technology’s potential for misuse, they were better able to see through industry boosterism – “Better living through chemistry!” – and recognize that there was a problem. But for the same reason, those at the forefront of the new environmental movement were strongly inclined to see technology, not as the means by which we could mitigate and undo the harms we had caused to the natural world, but as the very root of the problem.

Here’s how I put it in The Age of Abundance:

The new environmental consciousness was made possible by a fundamental change in the terms of humanity’s coexistence with the natural world. Throughout the 10 millennia of agricultural civilization, most people lived their lives in direct confrontation with natural constraints. Wresting their sustenance from the soil, subject to the vagaries of weather, pests, and disease, they pitted their efforts against a pitiless foe and prayed for the best. Famines and plagues on the one hand, deforestation and soil erosion and extinctions on the other – such was the butcher’s bill for the incessant and inconclusive struggle. Industrialization’s alliance between science and technology, however, broke the long stalemate and won for humanity an epochal victory: the creation of a world of technological and organizational artifice, insulated from nature’s cruelties and reflecting human purposes and aspirations. The cost of that triumph was immense, to humanity and the natural world alike. But when, in the middle of the twentieth century, Americans became the first people in history to achieve a durable conquest of nature, they were typically magnanimous in victory. Nature, the old adversary, became an ally to be cherished and protected; the environmental movement, a kind of Marshall Plan.

Yet, from its outset, that movement was afflicted with a heavy dose of victor’s guilt. Writing in 1962, Rachel Carson set the tone with her overwrought denunciation of pesticides, which she condemned as irredeemably toxic and symptomatic of deeper ills. “The phrase ‘control of nature’ is a phrase conceived in arrogance,” she proclaimed in Silent Spring’s concluding lines, “born of the Neanderthal age of biology and philosophy, when it was supposed that nature exists for the convenience of man.” In an influential 1967 essay that broadened and deepened Carson’s line of attack, the historian Lynn White located the roots of the “ecological crisis” in the most fundamental assumptions of Western civilization – that is, in the basic tenets of Christianity. “By destroying pagan animism, Christianity made it possible to exploit nature in a mood of indifference to the feelings of natural objects…,” White wrote. “Hence we shall continue to have a worsening ecologic crisis until we reject the Christian axiom that nature has no reason for existence save to serve man.”

The fundamental error that has plagued the environmental movement from its outset is thus the mirror image of the error it rejects. In agrarian and then industrializing society, people saw themselves in an adversarial relationship with nature – a zero-sum struggle that they rooted for humanity to win. The environmental movement preserved the zero-sum vision of the relationship between humanity and nature; its innovation was to root for the other side.

The environmental movement we didn’t get but which we have always needed – and which now, under the pressure of climate change, we may be finally making our way toward creating – is one that rejects this zero-sum vision and with it the twin impostors of technological naïveté and technological despair. Such a movement would have as its polestar a vision of harmony between man and nature – a vision in which human flourishing through technology serves to preserve and protect the flourishing of the natural world. There have always been seeds of this higher environmental synthesis in the actually-existing movement. Think of the remarkable career of Stewart Brand, who has always combined an ecological sensibility with enthusiasm for improving our tools: “We are as gods and might as well get good at it.” Or Richard Brautigan’s wonderful poem “All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace”:

One can imagine a world in which the dawning of environmental awareness instilled a sense of great technological challenge – and a sense of mission to rise to that challenge. Alas, that is not the world we were born into: In this timeline, environmentalism came into the world suffused with the spirit of anti-Promethean backlash.

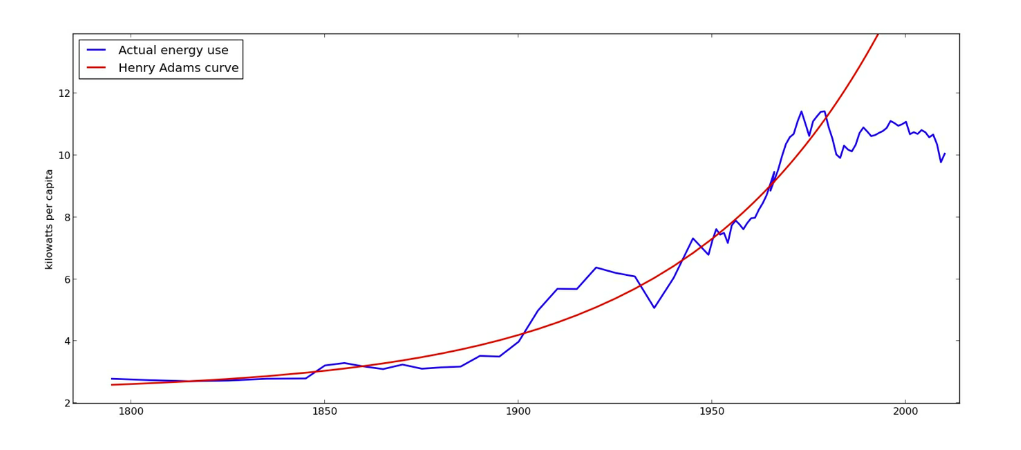

And this is what happened as a result:

This is a chart of U.S. energy consumption per capita, which until around 1970 showed steady exponential growth of around 2 percent a year. The author calls this the “Henry Adams curve,” since the historian was an early observer of this phenomenon. But around 1970, the Henry Adams curve met the anti-Promethean backlash – and the backlash won.

The chart comes from Where Is My Flying Car? By J. Storrs Hall. It’s a weird, wacky book that rambles all over the place; it’s also brilliant, and it changed my mind about a matter of great importance.

Before reading Hall, if I had seen this chart – and maybe I did see something like it before, I’m not sure – I would have had a completely different reaction. My response would have been along the lines of: “Wow, look at capitalism’s ever-increasing energy efficiency. We’re getting more GDP per kilowatt-hour than ever before, thanks to information technology and the steady dematerialization of economic life. All hail postmaterialist capitalism!”

But Hall argues convincingly that the plateauing of the Henry Adams curve didn’t represent the natural evolution of capitalism in the Information Age. The bending of that curve, he claims, constituted self-inflicted injury. Our midcentury dreams of future progress – flying cars, nuclear power too cheap to meter, moon bases, and underwater cities – didn’t fail to materialize simply because we were lousy at guessing how technology would actually develop. They failed to materialize because the anti-Promethean backlash, aided by loss-averse apathy, left them strangled in their cribs.

He is especially convincing on nuclear power. My prior impression was that nuclear power had always been a high-cost white elephant propped up only by subsidies, but Hall documents that back in the 1950s and 60s, the cost of new plants was falling about 25 percent for every doubling of total capacity – a classic learning-curve trajectory that was abruptly halted in the 1970s by suffocating regulation. In 1974 the Atomic Energy Commission was abolished and the new Nuclear Regulatory Commission was established. In the almost half-century since then, there has not been a single new nuclear power plant approved and then subsequently built.

Hall is also fairly persuasive that flying cars could be a reality today – they could have been a reality decades ago – but for legal and regulatory obstacles. Likewise, he makes a good case that the immense promise of nanotechnology has been subverted by scientific careerists who succeeded in diverting funds toward more business-as-usual research that they successfully relabeled as nanotech-related. He even has a plausible argument that “cold fusion” research actually did uncover interesting phenomena deserving of further investigation.

In my prior two essays, I’ve identified two factors behind capitalism’s decline in dynamism, both of them naturally occurring consequences of economic development: on the one hand, the exhaustion of low-hanging fruit; on the other, the growing power of loss aversion amidst rising material plenty. But Hall and further research inspired by reading him have convinced me that there’s more to the story. Capitalism didn’t just stumble; capitalism had its legs broken.

Energy is the ultimate general-purpose technology. The possibilities for the manipulation of matter to serve human purposes are to a considerable degree a function of how much energy we can throw at a given problem. For the last half-century and counting, we have basically given up the quest for new possibilities. We think of the “energy crisis” as something that happened in the 70s; we think of oil embargoes and gas lines. Well, worries about acute fuel shortages came and went, but it turns out that the energy crisis never really ended.

Hall’s book has caused a stir, especially in tech circles and among those interested in “progress studies” and an “abundance agenda.” His coinages – the “Henry Adams curve,” “ergophobia” (the fear of any sufficiently potent source of new energy as inherently menacing), and the “Machiavelli effect” (in which innovation always faces an uphill struggle, as those threatened by it are real and known while its beneficiaries are future and hypothetical) – are being picked up and recirculated. And his book, originally self-published, is now out in a handsome reprint by Stripe Press.

But Hall’s central contention – that the decline in dynamism is to a considerable degree self-inflicted – remains far from the conventional wisdom. And the main reason, I believe, is that our vision is blinkered by the limits of the social-science tools we use to make sense of things. The root of the problem is this: You can’t measure what doesn’t exist.

The way economists have approached this issue is to ask the question: what has been the effect of environmental regulation on economic growth? The question has received considerable attention, especially decades ago when the energy crisis was in the news and the dramatic drop in productivity growth was new and deeply puzzling. Given the coincidence in timing, many observers hypothesized that the productivity slowdown was the result of the rapid expansion of “social regulation” (i.e., health, safety, and environmental regulation) during the 60s and 70s. To measure the impact of environmental regulation, economists typically estimated the costs of compliance and then the effect on total output; because costs were now being incurred to produce an output not included in GDP (e.g., cleaner air), some negative impact on measured productivity was inevitable. Estimates varied, of course, but in general the compliance costs weren’t terribly high, and the industries subject to relatively high compliance costs accounted for a relatively small share of total GDP. Accordingly, the estimated impact of these extra costs wasn’t that dramatic. Meanwhile, when you add in the benefits of, say, cleaner air’s effect on health and well-being, the net welfare effect of most environmental regulations looks solidly positive.

But such estimates only capture the effect on the production of existing goods and services. They make no attempt to measure the welfare loss incurred because energy scarcity prevented the development of entirely new goods and services. They make no attempt to measure what dizzying heights output could have reached if only the progress of the Henry Adams curve had been maintained. Imagine if computer manufacturing were heavily regulated and that semiconductor technology had been basically regulated out of existence. Economists could estimate the impact of regulation on the cost of producing room-sized vacuum-tube behemoths, but that would tell us nothing about what we had actually lost by forgoing decades of Moore’s Law.

Furthermore, what changed wasn’t just the imposition of new regulations. What changed as well was the degree of government support of research and development. And more broadly, what changed was the whole culture’s orientation toward the future. Among educated elites, people more or less stopped thinking about the possibilities of harnessing vast new powers and physical capabilities. We continued to look forward to progress in health and medicine, and of course the rapid breakthroughs in information technology generated excitement. But as far as progress in the physical world of atoms was concerned, expectations shrank dramatically. Progress was redefined to mean cleaning up our messes, learning to live within limits by using resources more efficiently, and sharing what we have more equitably. In particular, the development of new energy sources like solar and wind was viewed simply as a means of replacing fossil fuels – not as a way of pushing past current limits toward energy abundance. Only now, in the past few years, are dreams of a bigger, bolder future starting to attract adherents again.

Hall constructs his narrative as a story with villains – namely, the nature-worshiping romantics of the environmental movement who led the anti-Promethean backlash. I understand where he’s coming from, but I can’t see it the same way. Although I can imagine an environmental movement that was ecomodernist from the outset, I don’t for a minute believe that such a movement was an actual live option that we somehow failed to choose. When the accumulating evidence of massive environmental degradation – dirty air, fouled lakes and rivers, iconic species on the brink of extinction, ubiquitous litter – finally sufficed to trigger a paradigm shift in people’s thinking, how could the dominant reaction have been anything other than horror and anger at the scale of the casual, thoughtless destruction? How could the immediate response to “what is to be done?” have been anything other than to try to restrain the technologies that were causing and threatening harm?

Ultimately, it’s the dialectical nature of history that is to blame. Yes, it would be wonderful if we could proceed frictionlessly from thesis to higher synthesis, but history rarely allows that shortcut. Rejection of the status quo is often the first step toward improving on the status quo; we need antithesis to open up the way from thesis to synthesis. There are some encouraging signs now that we may at last be groping toward a higher environmental synthesis – a synthesis in which we see humans and our technology not as standing outside of and apart from nature, but as that part of nature with the unique and vital responsibility of caring for the whole. Yes, we have made serious mistakes and we will have to pay for them: In particular, the problem of climate change is much harder today because of the widespread turn against nuclear power. But if we are now beginning to recognize those mistakes, and to find our way back to the path to a brighter future, it makes little sense to curse the steps that have brought us to this point.

Photo credit: iStock