“The Permanent Problem” is an ongoing series of essay about the challenges of capitalist mass affluence as well as the solutions to them. You can access the full collection here, or subscribe to brinklindsey.substack.com to get them straight to your inbox.

It’s my contention that 21st century capitalism is undergoing a triple crisis – one of inclusion, one of dynamism, and one of politics. As to the first of these, I’ve already written a couple of essays looking at the socioeconomic and political marginalization of ordinary people since the advent of mass affluence. Now I’ll turn to the crisis of dynamism. Piecing together what’s happened and why will occupy me for the next few essays.

We can conceive of this crisis in both narrower and more sweeping terms. As to the former, the concern is with declining rates of innovation and economic growth and growing barriers to scientific and technological progress. Zooming out and taking a larger view, there is the sense of a deeper, civilizational sclerosis. Ross Douthat calls it “decadence” – and I strongly recommend his insightful book on the subject. But I don’t think anybody can match the compactness and verve with which Ryan Avent of The Economist, in a Substack essay that deserves to be much more widely known and discussed, summed up the nature of what has happened in the rich democracies since the 1970s. He calls this past half-century “the conservative age,” and I’ll quote from him at length:

The notion that ours has been a period of intense, almost universally held conservatism may seem odd to some readers, particularly those of a nominally conservative bent. Hasn’t the state grown as a share of the economy, for decades? Hasn’t the observance of traditional religion declined? Haven’t sexual mores and gender norms been turned on their heads? And yet if the animating spirit of conservatism is the desire to command history to stop, and to preserve traditional practices across the breadth of society, the past half century can only be seen as the handiwork of a conservatism in near-total mastery of the flow of events.

From 1870 to 1970, the world was racked by violent change, across all spheres of human activity. National borders were drawn and redrawn. The residents of these shifting states experimented with the most radical forms of social organization ever attempted. Technologically, the world lurched from stagecoach journeys to landings on the Moon, from mechanical calculators to digital computers, from a near ignorance of “germs” to the study of our DNA. In the richest economies, incomes tripled, creating a large middle class and moving its members from a position uneasily close to subsistence to one of historically unprecedented wealth. Social relations — between sexes, races and classes — were upended. Culturally, the world experienced perhaps the greatest efflorescence of art ever: in literature, music, architecture, and just about wherever else one looked. It was an almost unbearably frenetic period of creative destruction, and destructive creation.

And then, around 1970, societies positioned at the frontier of human advance declared: enough. We went to the Moon; that was far enough. We grew tired of efforts to create utopia through our governments, and chose instead to enable the better heeled to consume the fruits of their labor by cutting their taxes. We began to freeze our cities in amber: by abandoning idealistic efforts to improve slums, prohibiting the replacement of the fine buildings of yesterday with the bold and the new, and shifting ever more of the population into the comfort and familiarity of suburbia. With rare exceptions, the energy and innovation bled out of our artistic endeavors. We lost interest in bold new political projects or grand reforming crusades; indeed we ultimately judged that we had found the best of all possible systems of social organization and declared that history had not only stopped but come to its very end. We made ourselves caretakers of a world built by our forebears — or less even than that: parasites upon it, draining what consumer comforts we can from it while they last.

The result has been a profound stasis, powered by a conservatism so deep and penetrating that we scarcely perceive it. To what do the ambitious among us aspire, today? To a structured life, repeating familiar steps: university, lucrative profession, comfortable retirement, modest thrills delivering anticipated rewards. We think our politics has become gridlocked because different factions have such different visions of the future, but that’s mistaken; our politics delivers very little, because even a little change is more than most of us are interested in. Seemingly radical shifts — in tolerance for same-sex relationships for instance — are achieved within an overarching social rigidity, in which power and class relations are preserved and the general order of daily life is undisturbed. Resistance to change has evolved into fear of the unknown; we have all been engaged in a paralyzing process of autoinfantilization, pursuing trivial comforts and eschewing risk.

I don’t necessarily endorse every element of this bill of indictment. In particular, I’m still not sure what to make of the claims of cultural stagnation – in certain popular art forms, sure, but overall is much less clear to me. And the turning away from utopian dreams was a sound move at the time, at least as long as the Cold War was still raging. But overall, I think Ryan does a fantastic job here capturing the essence of a profound civilizational shift – and identifying its character correctly as fundamentally conservative.

There are many different factors pushing this broad-based conservatism. But all share, in my view, common origins in capitalism’s transition to mass affluence and a postindustrial economy. In this essay, I’ll focus on the core concern over scientific, technological, and economic progress, and one very basic reason for the slowdowns we observe: Progress gets harder over time because of the exhaustion of the easiest opportunities for advance and generally declining returns to innovative activity.

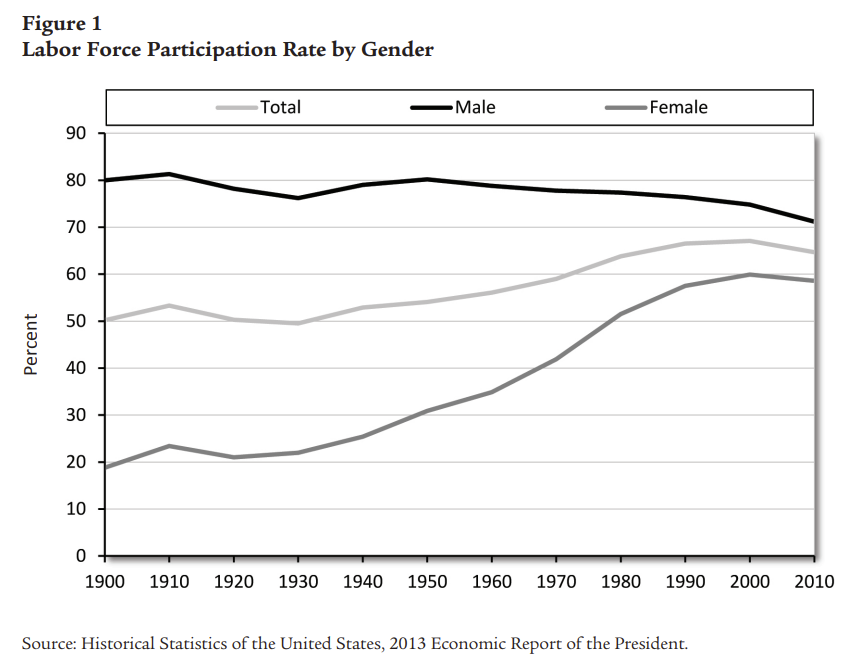

It turns out that major components of economic growth during industrialization consisted of one-off changes that took decades to unfold but then were more or less completed. In the United States, growth during the 20th century was accelerated by two demographic trends: the increasing mobilization of women into the paid workforce due to the automation of housework and widening job opportunities not tied to physical strength; and the upskilling of the population through increased years in school. The simplest way to raise GDP per capita over time is to increase the percentage of the population making GDP for a living, which is precisely what the transition of women out of the unpaid household sector and into the labor force accomplished. Between 1900 and 2000, the female labor-force participation rate climbed from 19 percent to 60 percent, causing the total LFPR to rise from 50 percent to 67 percent.

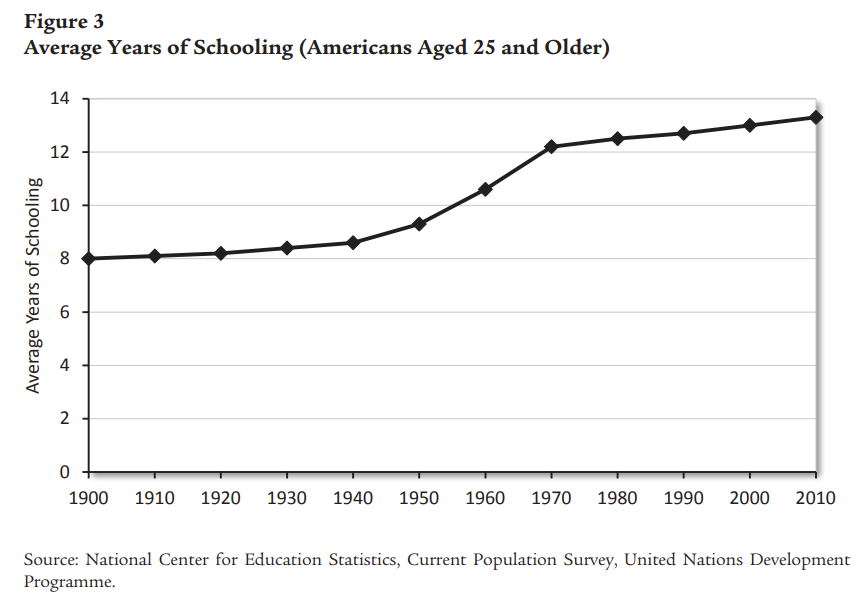

Beyond increasing the sheer quantity of labor inputs, you can also boost economic growth by improving the quality of labor: with more highly developed skills, a given hour of work can produce substantially higher value. And over the course of the 20th century, the United States saw dramatic surges in secondary and then tertiary education. In 1900, only about 6 percent of young people graduated high school; by 1970, it was up to 76 percent. In 1940, only 6 percent of young adults had a college degree; by 1980, 24 percent did. All in all, the average years of schooling for Americans aged 25 and older rose from 8.0 years in 1900 to 12.5 years in 1980. Harvard economists Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz estimate that some 15 percent of the total increase in GDP per capita from 1915-2005 can be attributed to the rise in educational attainment.

Mobilizing women and increasing years in school were processes that couldn’t go on forever, and so they didn’t. The female labor force participation rate stalled at the turn of the 21st century – still somewhat lower than that of men, but with only limited catch-up space left. And by 1980, the rapid run-up in educational attainment ended: From 1980 to 2005, the average years of schooling completed grew only 0.3 percent a year, compared to 0.8 percent a year between 1940 and 1980.

Once these changes were substantially complete, the tailwinds they provided to capitalist growth and dynamism subsided. Without a compensating speed-up in innovation and productivity growth, GDP growth would naturally subside as well. Since you could no longer rely on growth provided by increasing the relative quantity and quality of labor, you needed to substitute with growth from increasing the output per unit of labor.

Unfortunately, the same problems of exhausting the low-hanging fruit beset efforts to accelerate or even sustain productivity growth. In those sectors where productivity growth is easiest to achieve, that growth will eventually run ahead of demand for the products of those sectors. As a result, those sectors will shrink as a share of total economic output, and their contribution to overall output will be correspondingly diminished. Economic growth thus has this self-undermining dynamic: Over time employment and output will tend to concentrate in the least productive sectors. This isn’t a death sentence: If you can figure out how to rev up productivity in those reservoir sectors, you can keep overall growth from slipping. But without doubt, productivity growth gets harder over time.

We see this dynamic playing out over time in postindustrialization – that is, the shift from manufacturing to services. In general, productivity growth in manufacturing is higher than in services; labor-saving machinery can be added to the manufacturing process all the way to full automation, whereas human labor is often a vital component of service provision – it will always take four musicians to play a string quartet. But because of that fact, over time manufacturing has shrunk as a component of overall economic activity, and thus the economy has come to be dominated by services that are more resistant to automation and improved efficiency.

This is the phenomenon known as “Baumol’s cost disease,” named after the economist William Baumol who first identified it. Because of the productivity differential between manufacturing and services, the relative costs and prices of manufactured goods fall over time, and the relative costs and prices of services rise. Unless rising demand for manufactured goods can somehow keep ahead of this process, the result is that manufacturing as a share of total spending – and thus total output – will decline over time. And that’s precisely what has happened.

The cost disease phenomenon has an important implication – namely, that productivity growth can fall even if the pace of innovative activity in the economy stays constant, or even slightly accelerates. Let’s say innovation in both manufacturing and services stay constant, with the former at a higher rate than the latter. Over time, the shift from manufacturing to services will reduce overall productivity growth simply because the relative contribution from high-productivity manufacturing is now decreased.

The economist Dieter Vollrath contends that most of the decline in productivity growth in the 21st century is due to the shift from manufacturing to services – not, in other words, because of a slowdown in the pace of technological progress. In his book Fully Grown, he estimates that total factor productivity grew at an average annual rate of 1.51 percent between 1950 and 2000 – and that the average rate then fell to 1.26 percent during the 21st century (2000-2016). In other words, the productivity growth rate has fallen by 0.25 percentage points. Of that, he estimates that the shift from manufacturing to services during the 20th century reduced 21st century productivity growth by about 0.2 percentage points – or about 80 percent of the total decline in TFP.

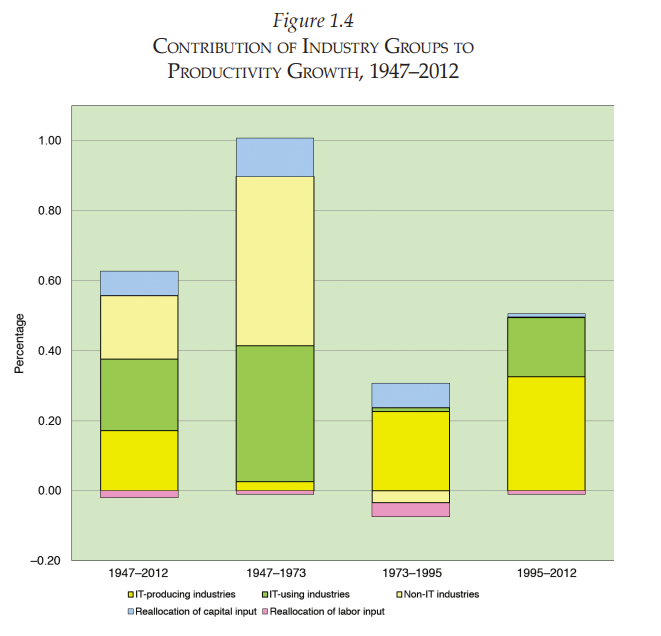

Nevertheless, there is genuine cause for concern about the current vitality of technological and scientific progress. First, just looking at aggregate productivity figures gives an unduly rosy picture, as it hides the total collapse of productivity growth in the world of atoms. Harvard economist Dale Jorgenson’s research on industry-specific TFP divides industry groups into IT-producing (computers, semiconductors, software), IT-using (including, among others, finance and retail), and non-IT. As the figure below shows, during the postwar golden years productivity growth was robust in non-IT industries; afterwards, the contribution of non-IT sectors to overall productivity growth completely disappeared. Now I recognize that calculations of industry-specific TFP growth involve all kinds of methodological assumptions and ought to be taken with more than a few grains of salt. Still, these figures suggest an alarming imbalance in the current state of innovation.

And then there’s the eyeball test. The economist Robert Gordon, well known for his techno-pessimism, has proposed the following thought experiment: Would you rather live with only pre-21st century technology, or have access to everything new from this century but give up indoor plumbing in return? His point is that this single innovation from the late 1800s dwarfs the combined impact of all technological change in the current century.

There is also suggestive if not definitive evidence that the rate of scientific progress is declining. Admittedly, it’s very difficult to draw conclusions about the whole of science. Some fields are more mature and the biggest breakthroughs were long ago (particle physics), while other, newer fields are booming (genomics, planetary astronomy, artificial intelligence). How is it possible to generalize across such disparate fields, and what is the measure of impact? Granting these difficulties of measurement, there are still some troubling signs that scientific research is bogging down. The average ages at which scientists are first published in a major journal, receive their first grant as a principal investigator, and perform Nobel Prize-winning work have crept up steadily over time. In the early years of the Nobel Prize, scientists were around 37 years old at the time of their prize-winning work; today, the average age is around 47. Publications and prizes now tend to go to teams of researchers rather than individuals, and team sizes are increasing.

The number of working scientists today and the number of new scientific papers published every year are both at all-time highs – and, ironically, that may be part of the problem. Researchers James Evans and Johan Chu explain:

The deluge of new papers may deprive reviewers and readers [of] the cognitive slack required to fully recognize and understand novel ideas. Competition among many new ideas may prevent the gradual accumulation of focused attention on a promising new idea…. When the number of papers published per year in a scientific field grows large, citations flow disproportionately to already well-cited papers; the list of most-cited papers ossifies; new papers are unlikely to ever become highly cited, and when they do, it is not through a gradual, cumulative process of attention gathering; and newly published papers become unlikely to disrupt existing work. These findings suggest that the progress of large scientific fields may be slowed, trapped in existing canon.

I’m not sure about a slowdown in the rate of overall scientific or technological progress. But what is indisputable is that progress per scientist or engineer is falling over time. In “Are Ideas Getting Harder to Find?”, economists Nicholas Bloom, Charles Jones, John van Reenen, and Michael Webb make the point that the number of researchers has skyrocketed over time – increasing over twentyfold since 1930 – while productivity growth has been flat or declining. Innovative activity has thus been experiencing sharply diminishing returns over time. To cite just one prominent example: The number of researchers required today to keep Moore’s Law going is over 18 times larger than back in the 1970s.

Their highly intuitive explanation is that these diminishing returns reflect the exhaustion of low-hanging fruit. Of course this isn’t the only possible explanation; it may be that our institutions for organizing and funding scientific research, and for translating that research into commercial products, are less efficient than in the past. But surely an important part of the story is that ideas are indeed getting harder to find.

A related idea is that progress gets harder over time because of the growing “burden of knowledge.” As the scientific and technological frontiers advance with every year, the years of study and training needed to reach the frontier – and thus be in a position to make a contribution of one’s own – necessarily increase over time. One reason ideas are getting harder to find, then, is that the preparation needed before the search commences is growing ever-more elaborate and taxing.

I don’t believe that the dynamics I’ve been describing here offer anything like a full explanation of the Age of Stasis. Other important factors are in play as well, and I’ll be exploring them in the essays to follow. But I wanted to start my investigation here because the exhaustion of low-hanging fruit and declining returns to innovative activity are inherent features of advanced capitalist development. We don’t need to identify bad guys, or find that a wrong turn was made years ago; rather, it is simply part of the nature of our social system that progress gets harder over time. That fact alone is sobering, as it means that the path of least resistance is toward torpor and stasis.