This is part 3 of a 5-part series. Read the full series here.

Albert O. Hirschman published a book in 1991 called The Rhetoric of Reaction, where he surveyed two hundred years of politics in Europe and the United States and identified three key tropes of conservative rhetoric (you can hear a thoughtful summary/discussion of the book here). Hirschman calls the primary rhetorical maneuver deployed by reactionaries “the perversity thesis.” He observes that it is extremely common for conservatives to oppose liberals and progressives by arguing that their desired courses of action are bound to have perverse, unpredictable effects — outcomes that are precisely the opposite of what was intended. To illustrate his point, he considers reactionary opposition to the French Revolution, to universal suffrage, and to the modern welfare state. In each case, conservatives claimed that progressive action would bring about a contrary effect. The Revolution would result in the exaltation of Christianity and monarchy in France, universal suffrage would result in despotism, and the welfare state would result in sloth and deprivation. According to the reactionaries, and here Hirschman quotes Joseph de Maistre, providence works like a “secret force which mocks human intentions.”

Deneen’s Why Liberalism Failed is like Hirschman’s perversity thesis on steroids. Deneen takes the standard reactionary trope — the idea that particular progressive actions will have particular regressive results — and applies it to liberal constitutionalism more generally. The central claim of Deneen’s book is that the more liberal democracy succeeds, the more it is doomed to fail; liberalism seeks the constant expansion of individual freedom, but, paradoxically, it just brings social dissolution, tyranny, and enslavement. He explains the causal relationship like this:

At the heart of liberal theory and practice is the preeminent role of the state as agent of individualism. This very liberation in turn generates liberalism’s self-reinforcing circle, wherein the increasingly disembedded individual ends up strengthening the state that is its own author. From the perspective of liberalism, it is a virtuous circle, but from the standpoint of human flourishing, it is one of the deepest sources of liberal pathology. (58-59)

This is a very big set of claims. Deneen does not do much empirically to demonstrate why he thinks people in modern liberal democracies all around the world today live pathologically and toil like serfs, but he does repeat his bloated version of the perversity thesis ad nauseum throughout (repetition being its own distinct type of rhetorical trope).

While it’s no doubt true that perverse outcomes sometimes occur in political life — human beings are complicated and political society is fragile, tension-ridden, and often frustrated by chance — Deneen’s overall argument is problematic in several key respects. First, it is built on false theoretical foundations: Deneen overstates both the consensual holism of pre-liberal politics and the individualizing nature of modernity, which means that he ends up obscuring the enduringness of both individualism and community in the history of political life and thought. Second, Deneen indulges in simplistic all-or-nothing thinking about political life today. In a modern context, Deneen only has eyes for individualism and tyranny, which means that he ignores all manner of existing “intermediary” political action, and has little to say about what actual contemporary government should look like.

On the so-called “individualist anthropology”

Deneen’s version of the perversity thesis depends almost entirely on the idea that radical individualism is a modern invention baked deep into the foundations of modern political thought and culture. But the story isn’t nearly so simple, either in theory or in practice.

For all of Deneen’s lamentations about modern atomism and individualism (modern politics is based on “the unfettered and autonomous choice of individuals” 31, “our default condition is homelessness” 78, and we live lives of “deracinated vagabondage” 131), the phenomenon he describes is not exactly new: selfishness and individualism have a long ancestry (!) that reaches at least as far back as ancient Greece. Ancient literature is full of characters who struggle personally with the duties imposed by convention — whether it’s Achilles wondering about a more natural mode of life away from war, Odysseus’ solo wanderings far from the constraints of domestic life, or Antigone’s religious struggle against state power. The most vivid depiction of rampant individualism that I can think of in antiquity comes from Thucydides — where the Athenians are depicted at times as selfish rationalists, in sharp contrast with the much more communal Spartans. But most major ancient political thinkers were interested in the question of how self-concerned individuals fit into the broader schema(s) of political life, and none of them assume that the answer is easy. In some ways, Plato’s Republic revolves around the question of what the individual owes to her community and vice versa: Should justice prioritize the good of the whole community, or the needs of the most deserving (or strongest) individuals? In the Politics, Aristotle says that the city is both “by nature and prior to” the individual because it is a whole on which we are all dependent, but he also says that “the good life is the chief aim of society, both collectively for all its members and individually,” and in Book 10 of the Ethics, he seems to make the contemplative, relatively self-sufficient, autonomous individual the divine peak and purpose of all existence. Is community for the individual, or the individual for the community? How does a thoughtful society contend with inevitable conflicts?

Deneen ignores these major themes of ancient thought, and instead writes as though the tension in modern thought between the individual and society were something altogether new and freshly problematic. And just as he conceals the role that individualism and autonomy play in ancient thought, so he neglects the role that the political community plays among modern thinkers. Deneen wants to tell a story of radical revolution and theoretical upheaval, but he has to distort intellectual history to make his case.

A lot hinges on what Deneen calls liberalism’s “individualist anthropology,” or the idea that liberalism posits a radically autonomous individual as “the normative ideal of human liberty” (57). According to Deneen, early modern contractualists like Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau each held that human beings are “by nature, non-relational creatures, separate and autonomous.” But the matter is not presented nearly so tidily by the philosophers themselves, who, in each instance, present the state-of-nature theory as either a hypothetical thought experiment or as a complicated aspiration, never as a matter of simple anthropological truth. Hobbes is explicit on the matter (“It may peradventure be thought, there was never such a time, nor condition of warre as this; and I believe it was never generally so, over all the world: but there are many places, where they live so now.”). Locke has a more aspirational account of the natural state — one that is more in keeping with the natural law tradition, and so avoids empirical questions of historical development (but is nevertheless not atomistic in any simple sense). But even Rousseau, whose Second Discourse reads far more like serious anthropological analysis, makes clear that the argument he presents is hypothetical, and perhaps sort of teleological, but not genealogical (“The researches which can be undertaken concerning this subject must not be taken for historical truths, but only for hypothetical and conditional reasonings better suited to clarify the nature of things than to show their true origin”). Rousseau does argue in The Second Discourse that human beings are isolated in their original, historical state, but he makes it clear in less famous works that he means this in a linguistic, communicative sense (i.e., before the advent of language, human beings were, for all intents and purposes, socially isolated and relatively alone).

Contra Deneen, the early modern contractualists did not make definitive anthropological or evolutionary claims about human nature. Instead, they offered abstractions and heuristics through which the reader might think more clearly about the conditions that legitimate political authority. Much as with Tocquevillian rhetoric, or as with Deneen’s own charged/hyperbolic style, there is a psychological and pedagogical power in the state-of-nature trope. By portraying people as peaceful and meditative by nature, for example, Rousseau arguably hopes to temper modern readers’ violent affect. In imagining the chaos that arises in the absence of stable government, Hobbes hopes to inspire appreciation for the idea of a simple, stripped-down sovereign. In neither case does this represent a theoretical abandon of ideals of community or civility. Even Hobbes’ darkest “state of nature” chapter (where he famously declares life in the state of nature to be “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short”) contains reminders about what government is good for:

In such condition, there is no place for Industry; because the fruit thereof is uncertain; and consequently no Culture of the Earth; no Navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by Sea; no commodious Building; no Instruments of moving, and removing such things as require much force; no Knowledge of the face of the Earth; no account of Time; no Arts; no Letters; no Society; and which is worst of all, continuall feare, and danger of violent death. (Leviathan, Book 1, Ch. 13)

Far from deriding social life and community, Hobbes is quite clear that, in his state of nature, things like “culture of the earth” and “knowledge” and “arts” and “letters” and “society” would be sorely missed. Having lived through civil war in England, he would know.

But Deneen is confident that Hobbes’ thought, like that of liberalism more generally, stands naturally in opposition to intermediary institutions:

Liberalism thus culminates in two ontological points: the liberated individual and the controlling state. Hobbes’s Leviathan perfectly portrayed those realities: the state consists solely of autonomous individuals, and these individuals are “contained” by the state. The individual and the state mark two points of ontological priority. (38-39)

Now, the idea that liberalism culminates in Hobbes is a bit silly, since (as Deneen at points acknowledges) Hobbes’ status as a liberal is highly contested. But the real difficulty here is that Deneen ignores the tension that exists within liberalism between these two “ontological priorities.” The thing that distinguishes a liberal order from an authoritarian one is that the former is designed to protect individuals — as well as all manner of civic associations — from overweening state power. Even if we grant Deneen’s notion of liberalism’s ontological priorities, it’s not like the two poles exist in simple harmony. There are standards by which liberals get to judge Leviathan.

Deneen writes as though the early moderns were out to destroy the bonds of affection, community, and political life, when in fact they were forging and imagining new conceptions of political community in complicated and conflict-ridden contexts. The so-called “individualist anthropology” he describes is best understood as a hypothetical proposition that serves to illustrate concepts of legitimate, consent-based authority (as opposed to limitless, unstable, and often arbitrary power of theocratic monarchies, or, in the 20th century, of totalitarian regimes). Deneen is right that this modern way of thinking about politics often gives pride of place to assent of the governed (“Liberalism begins a project by which legitimacy of relationships becomes increasingly dependent on whether those relationships have been chosen,” 32), but dead wrong when he reduces all modern liberal thinking to narrow self-interest (“What was new is that the default basis for evaluating institutions, society, affiliations, memberships, and even personal relationships, became dominated by considerations of individual choice based on the calculation of individual self-interest, and without the broader consideration of the impact of one’s choices on the community, one’s obligations to the created order, and ultimately to God,” 33-34). The idea of a radicalized “individualist anthropology” is not quite a fiction, but it is a way of framing early modern thinkers like Hobbes and Locke that is misguided, reductive, and decontextualized. Deneen is hardly the first person to take such an approach to these thinkers — so-called “Straussians” do it all the time, and I have often done so in my undergraduate teaching, too. When the (theoretical) fate of liberal modernity hinges on one’s interpretations, however, it is important to be more careful.

By choosing to connect his theory of democratic decline so closely to the supposed “anthropology” of the early modern contractualists, Deneen also evades serious engagement with those who have critiqued Hobbesian individualism and materialism ever since. In the long history of political thought in Europe and the United States, there have been many thinkers ready and willing to push back against the individualist thrust of Locke and Hobbes, and who have helped to ensure that radical atomism never gained full traction on the modern constitutional mind. There was Montesqueiu (1689-1755), for example, who was deeply invested in exploring the institutional mechanisms through which despotism might be avoided, who was always careful to highlight the importance of local customs and practices, and whose works influenced the American Founders. Then there is the aforementioned Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778), whose works did include an individualizing state-of-nature thought experiment, but who also wrote compellingly about political structures and legitimacy, the need for religion and morality, as well as other cultural forms that he deemed compatible with modern freedom (Rousseau wrote novels and did a lot of botanizing — both of which thought could enrich modern life). From here, one could turn to the works of foremost modern thinkers like Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), Germaine de Staël (1766-1817), Benjamin Constant (1767-1830), and Alexis de Tocqueville (1805-1859), each of whom was deeply interested in questions of ethics and political culture, soundly rejected the notion that simple self-interest could uphold healthy politics, and acknowledged the important role that religion plays in political life. These thinkers are all just as relevant to the intellectual history of liberalism as Bacon, Hobbes, or Locke, and each of them rejected the “individualist anthropology” that Deneen peddles as foundational (on this point, see Helena Rosenblatt’s The Lost History of Liberalism, especially chapter 2).

Finally, there are all those who have written about liberalism — and rejected liberal atomism — since the 19th century, and still operating within the traditions of democratic constitutionalism broadly conceived. Suffice it to say that, just as Deneen selects choice passages and concepts from Hobbes and Locke, to the neglect of other early thinkers, he is quite capable of doing the same with Dewey and Rawls and Rorty. He whittles down their thought selectively, shapes it how he likes, and presents it as some core of liberal theory — while remaining silent about other rich avenues of thought that have circulated throughout the tradition for the last hundred-plus years. Deneen is mostly silent about the generations of feminist, Black, and postcolonial thinkers who have challenged individualizing capitalist influences (but without rejecting liberal constitutionalism), has very little to say about the emergence of new, successful liberal democracies around the world in the second half of the 20th century, and basically ignores the waves of human rights theorists who have challenged the individualist tenor of early liberal theory. What is more, Deneen neglects all those more contemporary thinkers — liberal theorists, communitarians, existentialists, small-r republicans — who questioned, and continue to question, the identification of modern republicanism and liberal democracy with narrow individualism (while still operating within the tradition of liberal constitutionalism broadly conceived — the list here is long, but some of the heavy hitters include Hannah Arendt, W.E.B. DuBois, Isaiah Berlin, Ronald Dworkin, Judith Shklar, Sheldon Wolin, Charles Taylor, Michael Sandel, Jürgen Habermas, Cornel West, Martha Nussbaum, Will Kymlikca, and Danielle Allen).

I am not an expert in contemporary liberal thought — indeed I have spent more time with liberalism’s critics — but even I can see that Deneen simply isn’t a reliable narrator when it comes to the subject of his own book.

Deneen’s Goldilocks view of politics

As we have seen, the idea of radical modern individualism plays a powerful role in Deneen’s work. But radical individualism isn’t just something that he projects onto the books he reads; it also colors his view of the world around him. He looks at contemporary affairs and sees only individualism and statism, which are always bad, and this makes it awkward when he tries to acknowledge or articulate a positive role for government (awkward in the sense of sounding strictly partisan and arbitrary).

Not too big…

According to Deneen’s theory, individualism acts as a solvent on all social relationships and mediating institutions, and, in a vicious cycle of sorts, despotic government comes in to fill the void. Deneen seems to believe in this theory strongly, and he sees evidence for it everywhere — even, say, when he’s talking about action taken by democratically elected representatives to achieve goals that large majorities believe benefit their common well-being. No matter what the government is up to, it’s just individualism-infused despotism all the way down. In reading Deneen, as with so many conservatives, one wonders what government is ever good for (Brink Lindsey of Niskanen writes about the history of this problem here).

I don’t recall Deneen ever speaking well of anything done by the modern state, and he speaks especially sneeringly of social democracy and progressivism, which aim at “complete liberation from the shackles of unfreedom” and “a new and better individuality” (54ff). The most tangible and specific target in Deneen’s book may be a silly political ad from President Obama’s 2012 campaign. The advertisement takes the form of a series of interactive slides depicting “the life of Julia.” Julia is an American citizen who hypothetically benefits from government programs at various milestones throughout her life under Obama that would not exist under a President Mitt Romney. Julia may have merely been a character in a political advertisement, but for Deneen she represents so much more. She is “the most perfectly autonomous individual since Hobbes and Locke dreamed up the State of Nature,” and the culminating point in his theory of liberal dissolution: “In Julia’s world there are only Julia and the government … Julia has achieved a life of perfect autonomy, courtesy of a massive, sometimes intrusive, always solicitous, ever-present government.” For Deneen, even the “government-sponsored yellow bus” that Julia’s child takes to school is a bleak sign of despotic power. I won’t go on more about the “Life of Julia” campaign, but it does seem worth pointing out that 1) Julia wasn’t real, and 2) Obama’s political campaign had to do with specific government programs, and so it makes sense that the rest of Julia’s (possibly very rich) life was excluded from the ad.

The more significant point is that, according to Deneen’s book, anything created or sustained by the government — from public health care, to school buses, to palliative care — is inherently despotic, because the very act of governance creates dependency and destroys community bonds. And he is quite convinced that the state takeover of our lives has already happened — that government has “shorn people’s ties to the vast web of intermediating institutions that sustain them” (61). The flipside to such an assertion is that (in the book), there is no level of government involvement that Deneen is willing to defend, and no action on the part of public officials that he deigns to deem appropriate.

This way of thinking about government also ignores the complexity and local embeddedness of actual government action. Public schools might enjoy federal funding, but yellow bus services are still local affairs, organized by local bureaucracies and filled with local kids. And in reading Deneen’s work it’s easy to lose track of the fact that governments are actually constituted by public servants — i.e., fellow human beings who make up parts of communities in actual places. Deneen says that the modern state has replaced all “non-liberal forms of support for human flourishing” and lists “schools, medicine, and charity” among his examples (62). But just because my child rides a “government-sponsored yellow bus” or sees a doctor supported by a federal program, this does not mean that her driver or physician are “shorn” from our community, or us from theirs. Deneen’s point seems to be that it is always inappropriate for people to create such institutions through their collectively-chosen government representatives; he renders government as such illegitimate. As others have noted, post-liberals like Deneen have real contempt for actual existing institutions.

It’s worth reiterating that Deneen’s expressed views of contemporary political action are so cynical that it’s hard to see what, if any, standard he uses to judge — or to limit — actual political behavior. Often it seems as though he isn’t just anti-liberal, he’s anti-political (taking “political” to mean processes whereby power is shared and contested among political equals, as opposed to rule by mere force).

Not too political…

So what kind of collective action does Deneen encourage and support? In the book, the sweet spot for Deneen seems to be nongovernmental, informal community decision-making. He has obvious affection for the Tocquevillian association, as well as for ancient republicanism, and he likes the idea of people coming together to solve local problems. His conclusion involves an invitation to new intentional communities or communities of practice where people will learn old-fashioned household economics anew (the communities will be grounded in what Deneen calls “virtuosity within households”), as well as learning to sacrifice their own well-being on behalf of the larger group: “from the work and example of alternative forms of community, ultimately a different experience of political life might arise, grounded in the actual practice and mutual education of shared self-rule.” Deneen hypothesizes that such communities will, at the beginning, benefit from the openness of liberal society, but are likely to end with reinvention: He predicts that people will start rethinking their individualist anthropological assumptions, and will start to question the value of a “world-straddling state and market.” He looks forward to a new era of deeper cultural consent and community, to new accumulations of practice and experience that can be passed along as a gift to future generations (190).

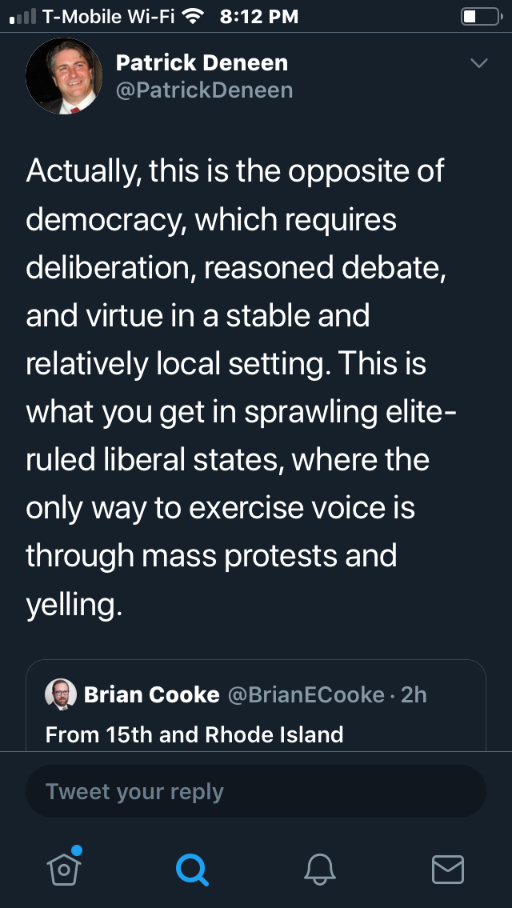

Deneen’s concluding chapter contains some insights of value. It provides a wholesome articulation of important civic ideals — dimensions of a healthy social and civic fabric that are often neglected or taken for granted, and which probably bear repeating these days even if they sound naive. The problem that I see in Deneen’s summary conclusion is not so much the substance of what he recommends, but rather his failure to put these recommendations in clear political context, as well as his failure to acknowledge all the work that is already being done — both culturally and politically, at the community level, and often by liberals and leftists — in a similar vein. Deneen writes about intentional communities, local practices, a new emphasis on handiwork, community-building, power-sharing, and equity as though he were the first person in late-stage capitalism to recognize the value of such things, and as if no one around him has actually yet engaged in the world this way. Forget Jane Jacobs, environmental sustainability, millennial minimalism, local food cooperatives, or grassroots social movements: By neglecting these and other very standard appeals from the left, Deneen avoids the fact that modern liberal reality already contains or aspires to much of what he describes as new and needful. Deneen loves to rail against corporations and the global economy, but he fails to credit the left for their actual proposals on this front. As Greg Sargent of the Washington Post put it in July, why won’t conservative populists like Deneen acknowledge that, “in important respects, economic progressivism really does offer very developed answers to things like deindustrialization and rural v. cosmopolitan regional inequality”? The culminating suggestion of Deneen’s book is that we are in desperate need of alternative forms of politics, economics, and community. My point is that some of this is already happening in obvious (if still too limited) ways. Perhaps the fact that Deneen doesn’t acknowledge or discuss these efforts on the left is an indication of how these other perspectives simply don’t count, to him. I am not the first to suggest something along these lines. Hugo Drochon observes that conservatives like Deneen “seem to believe the communities and cultures that liberals share somehow don’t count,” and notes Deneen’s refusal to engage with the liberal tradition of pluralism. I have in mind something more tangible, though. In a tweet from this past summer, Deneen suggested that a peaceful march from the George Floyd protests was the opposite of “what democracy looks like,” since democracy “requires deliberation, reasoned debate, and virtue in a stable and relatively local setting.” Deneen has since deleted this tweet (you can see a screenshot below), but it does suggest a political aesthetic whereby anything that departs from his romanticized classical or Tocquevillian ideal simply doesn’t count. I do not imagine that he takes very seriously any of the democratic political action that has swept the country since 2016 — from the Muslim-ban protests and Climate and Women’s Marches to the record-setting voter turnout in 2018, and now in 2020. Nor do I imagine that Deneen sees traditional political organizing as an important form of civic engagement — sullied as it is by, well, politics.

Some big government is Very Good

What Deneen doesn’t tell us about in his book against liberalism, but has been more open about recently, is that ultimately for him the standard by which we should judge political life isn’t constitutional or political, it’s cultural and it’s theocratic. We see this in his work on Aristopopulism as well as his willingness to defend integralism. In describing Aristopopulism, Deneen envisions (“in the spirit of thinking out loud”) all kinds of broad new government policies that arguably recall Aristotle’s “mixed regime.” Deneen’s intention is to facilitate better representation for non-elite rural actors (“somewhere people”) in government and the genuine mingling of classes in American life. His proposals include the reintroduction of mandatory military service, the public takeover of “liberal cities” of the kind recommended by Ross Douthat, a loan forgiveness/tuition program hinging on service-minded work or relocation to remote locations, the thwarting of free market and free enterprise institutions (“a Machiavellian assertion of a popular tumult should be directed at either preventing such abuses of financial power or seeking to dismantle such institutions”), and the pursuit of a censorious “moral media.” Some of these proposals sound, I think, just fine, while others sound a bit sinister. The more important point is that many of them sound like variations on what he elsewhere refers to as (bad) statism.

(It’s worth noting that one significant difference between Deneen’s proposals and those typically promoted by the left is that Deneen’s aim is to further empower rural “somewhere” people, who he believes have been left behind. He does not seem concerned with the urban and suburban working class. As Jamelle Bouie has pointed out, Deneen’s account of who counts as working-class is “completely cultural” and “entirely white.”)

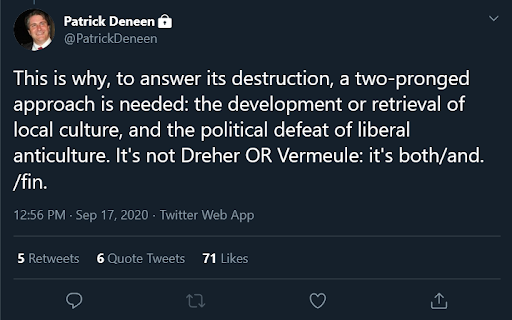

More recently Deneen has become even more open about his support for (some) big government programs. As he put it once on Twitter, to answer the destructive forces of liberalism, a “two-pronged approach is needed”; he then advocates for a both/and of Rod Dreher’s Benedict Option localism, and Adrian Vermeule’s integralism. Integralism is a way of thinking that, like Deneen, actively rejects liberalism, but which, in contradiction with Deneen’s book, is very supportive of a strong, active, administrative state. Integralists like Vermeule hope to bring about a more openly theocratic kind of rule in America via a gradual infiltration of the government on the part of religious individuals. As Vermeule puts it in a controversial piece for The Atlantic last March, “Unlike legal liberalism, common-good constitutionalism does not suffer from a horror of political domination and hierarchy, because it sees that law is parental, a wise teacher and an inculcator of good habits.”

It turns out that, when all is said and done, Deneen is not at all against a strong central government per se. He harbors no admiration or respect for existing institutions, but is happy to support the idea of a hypothetical state that serves his preferred (reactionary) cultural and ideological preferences.

The proof is not in the pudding

In what I take to be a culminating move of intellectual bad faith, Deneen devotes one of the final chapters of his book to spinning the existing evidence of liberal well-being into a rickety smear. The chapter is called “The New Aristocracy,” and it’s all about the bad liberal elites who make up what he calls the “liberalocracy.” Liberalocracy is the word Deneen uses to describe the new political order that has allegedly taken over America. Basically, it’s the tyrannical form of bureaucratic rule that was so all-encompassing for Obama’s fictional Julia — and which, presumably, is altogether different from what we should expect to see under Vermeulism or Aristopopulism.

Now, conservatives of all stripes have long decried the role of the federal government in American affairs, but in his book Deneen takes the trope to a whole new level. In the course of a work that argues that liberal democracy has failed, and that its failure can be traced to its individualizing success, Deneen still has to confront the evidence that there are whole swaths of people in the U.S. who are doing very well, even by his own localized communitarian standards. Deneen cites the work of men like Robert Reich, Christopher Lasch, Charles Murray, and Robert Putnam to argue that liberal elites (“liberalocrats”) are more likely to have things such as lasting marriages, high levels of education, financial stability, and opportunities for fulfilment. This would seem to be a real problem for his theory, since it suggests that the very same people who are most representative of a liberal outlook are the ones who are thriving within it. If liberalism is self-destructive in the way Deneen claims it is, shouldn’t liberals be the most deracinated of all?

Deneen does away with this problem by interpreting the life and behavior of liberals (and, of course, a good number of “conservatives”) in ruthless and cynical terms (I have elsewhere written about how Yoram Hazony takes a similarly dehumanizing view). He argues that the liberalocratic lifestyle is entirely exploitative, and that the exploitation is entirely by design. Instead of acknowledging that, for all its very real injustices, shortfalls, and hypocrisies, liberal democracy has not been a total failure, Deneen takes a more radical line: Everything that bourgeois liberals do is in bad faith.

Rather than confront the real limits to his own theory of liberalism’s collapse, Deneen argues that beneath the veneer of ordinary middle-to-upper-class American life lies historically unprecedented calculation and cruelty. Deneen’s liberalocrats are all entirely corrupt; their every pursuit is transactional and shallow. Friendships for them are “like international alliances, understood to serve personal advantage”; education always amounts to mere careerism; marital stability is just one more “form of competitive advantage” and the adoption of familial forms “by the strong is now one more tool of advantage over the weak” (134). Unlike, I presume, all other people in positions of relative power throughout history, liberalocrats are only successful because they have exploited others: “Such individuals flourish in a world stripped of custom, and the kinds of institutions that transmitted cultural norms, habituated responsibility, and cultivated ordinary virtues” (151). And none of it is accidental: “This scenario was embraced by those of liberal dispositions because they anticipated being its winners” (135). Marxists at least have the decency to credit the bourgeoisie with false consciousness.

With his theory of the New Aristocracy, Deneen takes the fact that millions upon millions of Americans are experiencing well-being, according to his own social metrics, and spins it as ugly exploitation. For him, when ordinary non-liberalocrats go to college, get married, join a church, or engage in their local community, it’s a wholesome stepping-stone to the future — and exactly what America needs. When liberalocrats do these same things, it’s shameless artificiality and ruthless exploitation all the way down. In his more recent work on Aristopopulism, Deneen expresses a sincere hope that today’s liberalocrats might be replaced by more authentic Aristocrats (again, he recommends “an aggressive confrontational, punitive, trust-busting political strategy aimed at taming the elites, that in turn will result in a tutoring of the elites towards a concern for the common good”). In a March review of Michael Lind’s book The New Class War, Deneen puts it like this:

What’s needed is a fundamental displacement of the elite ethos by a common-good, popular conservatism that directs both economic goals and social values toward broadly shared material and social capital, toward the support of family and community life … Only the fear of not conforming to the regnant ethos will sufficiently move elites, but that fear will arise subsequent to the wholesale defeat, displacement, and discrediting of the regnant elite ethos …The power sought is not merely to balance the current elite, but to replace them. In the end, there is no “functional equivalent” of solidarity and subsidiarity, and only a leadership and working class steeped in such values will restore the republic.

Far be it from me to defend every middle-class, or wealthy, or educated American, or every public servant, at a time when inequities are so gross, hypocrisy is so common, and so many are struggling so much. But it’s possible to recognize the inequalities and injustices of the status quo and still see that Deneen’s theory of “liberalocracy” is slightly absurd, and his hopes for the forced emergence of new Aristocratic unicorns more than a little fantastical. Josh Hawley just isn’t up to the job.

The intransigence is the point

It takes a lot of work to sustain the idea that nothing is what it seems, and Patrick Deneen probably put a lot of work into Why Liberalism Failed. According to him, a concern for individual-consent-based liberty leads inevitably to rabid tyranny, and the apparent success of society’s most “liberal” group is actually abject failure. His is a perverse and topsy-turvy world. In order to sustain the illusion of uncanny opposite effects, Deneen sees what he wants to see in the texts of the past, ignoring inconvenient passages, books, and authors. He does the same with the world around him, refusing, for the most part, to recognize actual existing political or collective action as legitimate, and interpreting existing social success stories as necessarily debased and corrupt. It’s a pattern of persistent evasion and fuzzy incoherence, grounded in ideology and latent romantic idealism.

Hirschman concludes his book on reactionary rhetoric with a discussion of the analogous habits of progressives, showing how the two political forces tend to go back and forth with inverse and opposite responses. Whereas reactionaries argue that liberal actions have perverse effects, progressives respond by saying that the absence of action will prove catastrophic. Of course, depending on the actual reality of things, at some point either side could be right. In the end what matters more to Hirshchman than this tiresome back-and-forth is figuring out who, at any given time, comes closer to understanding the world. Fittingly, and with this ultimate goal of truth and understanding in mind, Hirschman concludes the book with an argument against intransigence.

Hirschman is interested in citizens learning to engage with one another more openly and truthfully, in the hopes that they might come to understand each other more fully, so that in the end they might approach their shared lives with more comprehension and generosity. Hirschman warns that, for meaningful discussion to take place between the different political forces within a democracy, participants must be ready “to modify initially held opinions in the light of arguments of other participants and also as a result of new information which becomes available in the course of the debate” (169). It is difficult, after all, even at the best of times, to really understand what is going on in political life; openness to alternative accounts and new evidence is crucial. The democracy-friendly kind of dialogue that he envisions would avoid making arguments like the perversity thesis that are “in effect contraptions specifically designed to make dialogue and deliberation impossible” (170). Once a person buys into something like Deneen’s inevitability thesis, or the notion of the “liberalocracy” — or simplistic accounts of Marxist determinism, or any other over-simplifying dogma — then there’s not much point in conversing. The odds that minds will change are almost null. Political freedom is shut down.

Hirschman’s ideas about intransigence strike me as true, and it’s clear that intransigence can be a problem across the political spectrum, since acknowledging one’s ignorance is so painful. What is striking about Deneen, however, is how thoroughly he has turned his back on the kind of democratic project Hirschman describes. For all his talk about local deliberations and shared governance, for all his interest in mixed regimes and the mingling of classes, and for all his talk of liberal education, Deneen’s outlook is a sound rejection of the genuinely liberal aims and assumptions that Hirschman is wedded to — including openness to contradictory ideas and alternative perspectives.

In the next section I turn to Deneen’s radically anti-liberal, anti-intellectual take on education and freedom. Deneen’s discussion of the liberal arts reveals that the civic deliberations he has in mind take place exclusively within particular cultures and communities, rather than across any lines of real political difference. Deneen’s understandings of education and freedom are extraordinarily pinched and confined.