This is part 2 of a 5-part series. Read the full series here.

Some 30 years ago, Francis Fukuyama famously declared liberal democracy to be singularly ascendant. Two years ago Patrick Deneen declared it defunct. Who is closer to the truth?

A lot has happened in global politics since the early 1990s, much of it very bad, some of it very good. In my adult lifetime I’ve seen ongoing environmental exploitation, the Iraq War, the rise of the War on Drugs and mass incarceration; I’ve also seen the fall of the Berlin Wall, the end of apartheid in South Africa, the taming of HIV/AIDS, and major strides in clean energy (just to count a few things that Deneen and I would surely agree are good). But the story Deneen tells, and that other reactionaries like Michael Anton and Bill Barr seem to agree with, is one of simple long-term decline. By Deneen’s telling, the social and political foundations of all modern liberal democracies have — at some point along the way, hard to tell when — shifted dramatically, and only for the worse. I imagine that one of the reasons that Why Liberalism Failed proved so popular is that it takes such a single-minded view, but it is a strange set of distortions concerning an obviously complicated trajectory. In this section I consider some of these distortions systematically.

Deneen’s work begins with a reductive definition of liberalism that cherry-picks within liberal democracy’s rich genealogy. He focuses on individualism and the conquest of nature, and jettisons more standard “hallmarks” of liberalism. Then, as he sets out to answer the question posed by his title — i.e., to explain why it is that liberalism failed — Deneen tells a lopsided story that romanticizes the past and is decidedly dystopian about the present. The book fails to articulate any clear standard by which we might reasonably adjudicate political realities, and ends with hazy appeals to localism and community. Deneen’s concluding chapter actively avoids theoretical clarity and leaves the door to localized authoritarianism and theocracy wide-open. All in all, the methodology here leaves something to be desired.

A reductive conceptual framework

I have written before about Patrick Deneen’s narrow understanding of liberal democracy — and, in particular, how he and others tend to lean on old neutralist conceptions of liberalism that were popular in the 1980s as a way of undercutting the normative heart of liberalism (which is not merely about individualism, but also about freedom of conscience, dignity, and the cultivation of peace and well-being, among other things). Here I want to begin by saying something more straightforward about Deneen’s overall approach — about how, when it comes to testing and proving his central causal claim about decline, he dodges engagement with some of the most obvious variables.

Deneen is a political theorist, not a political scientist, and I do not mean to imply that he should have written a book of political science research (as Jason Blakely has observed in his work on Adrian Vermeule, it’s quite possible to use “the sober findings of social sciences” as a cloak for dangerous/authoritarian ideas). But the social sciences aside, Deneen’s big thesis is that liberalism failed because it became the victim of its own success (“Liberalism would thus simultaneously ‘prevail’ and fail by becoming more nakedly itself,” xiii; “liberalism has failed — not because it fell short, but because it was true to itself. It has failed because it succeeded,” 3). Presumably, in accounting for this kind of causal claim — X became more itself, thus causing its own decline — the definition one begins with matters. To understand whether liberal democracy caused its own decline, by virtue of its true nature or essence, we need to know what that essence really is. Unfortunately, when Deneen settles on a definition of liberalism, he does so reductively and idiosyncratically, and in a manner that evades standard conceptions of what liberal democracy actually involves. In other words, Deneen argues that liberalism fails by being too much itself — too atomistic, too unnatural — but these things hardly constitute liberalism’s telos or core.

As a theorist it is always difficult to establish stable definitions (as Blakely puts it, “liberalism should be thought of more like a literary genre, with new forms and innovations continually emerging”). But still, in the opening pages of his book, Deneen himself provides us with just such a standard definition of liberalism. He identifies “limited but effective government, rule of law, an independent judiciary, responsive public officials, and free and fair elections” as some of the “hallmarks” of liberalism (1-2). This strikes me as a reasonable list. In her book, The Lost History of Liberalism, Helena Rosenblatt shows how many of liberalism’s earliest defenders came to a similar standardized conception, emphasizing “equality before the law, constitutional and representative government, and freedom of the press, conscience, and trade” (62, see also 71). So, while the history of the word has shifted around in complicated ways since then, Deneen’s “hallmarks” constitute a decent working definition of the thing. It seems reasonable to expect that the “hallmarks” of a thing would be among its defining features, such that, according to Deneen’s thesis, the “hallmarks” of liberalism would be among the things that, by becoming more truly themselves, would also contribute to the supposed failure. Unfortunately, the book does not address the successes and failures of the actual “hallmarks” of liberalism in any systematic way. Deneen does not dare to argue that by establishing things like limited government, equality before the law, free and fair elections, independent courts, etc., society tends to unravel.

Instead, Deneen pivots early on away from a standard conception of liberal democracy and draws his own alternative portrait. According to Deneen, liberalism proper is animated not by its hallmark features or standard attributes or aspirations, but by “two foundational beliefs.” Undergirding every liberal state is a radical belief in “anthropological individualism” and “in the human separation from and opposition to nature” (31). With this, Deneen reconstructs and redefines liberal democracy in a way that minimizes the role played by political structures and protections. He refocuses on two alleged ideological positions, which, in turn, threaten everything else: These foundational liberal ideologies have already turned politics, government, economics, and education into the “iron cages of our captivity.” In addition to shifting attention to an allegedly all-powerful ideology, Deneen also makes quick work of the “hallmarks” of liberalism by suggesting that they were actually not liberal at all, but rather the inheritances of other pre-liberal traditions and legacies:

Many of the institutional forms of government that we today associate with liberalism were at least initially conceived and developed over long centuries preceding the modern age, including constitutionalism, separation of powers, separate spheres of church and state, rights and protections against arbitrary rule, federalism, rule of law, and limited government. Protection of rights of individuals and the belief in inviolable human dignity, if not always consistently recognized and practiced, were nevertheless philosophical achievements of premodern medieval Europe. (22)

One might quibble here about the relative importance of “philosophical” versus actual achievements, but even granting that Deneen is correct about the genealogy of liberalism’s hallmark institutions, a mixed-up lineage hardly diminishes the ontological integrity of a thing. My children have grandparents and parents, but they are still their own little beings. When Deneen reduces liberal democracy to two ideological flashpoints, to the exclusion of its other signature inheritances and innovations, it’s a manipulative, anti-historical projection. As Samuel Goldman observes in his review of Why Liberalism Failed, Deneen’s account of liberalism amounts to a theoretical “just so” story, or Geistesgeschichte: “It reaches back into the past to explain why things must be exactly as we find them today, without acknowledging nonintellectual factors, contingency, and just plain chance.”

But this stunted set-up is necessary to the bigger story that unfolds. Deneen is only able to make a plausible case for liberalism’s self-destructiveness once he has reduced the tradition, deconstructed it and defined it down. After all, if radical individualism and opposition to nature were the true essence of liberal constitutionalism, then it would in all likelihood necessarily falter (and to the extent that Deneen’s work is useful, it’s because it depicts that possibility so glaringly). A more serious and honest assessment of modern liberal democracy would not jettison its hallmarks in favor of theoretical perversions.

Opaque evaluative standards

A second major methodological problem with Deneen’s work is that his evaluative standards remain almost entirely opaque. Deneen’s title confidently declares liberal modernity a failure, but against what standard does he render this bold judgment? When were things really much better? For Deneen (much as with Trump’s MAGA-loving supporters), the answer to this question seems to be “before.” But instead of demonstrating any kind of clear and precipitous change from better to “failed” historical conditions, Deneen proceeds unsystematically. His introduction begins with some lazy, citation-free references to public opinion (“70% of Americans believe”; “It is evident to all that”; “A growing chorus of voices even warn that”), and then proceeds primarily via hyperbolic assertions about the present. The book is full of nostalgic reminiscences about the past, but he leaves it up to the reader to intuit the actual standard against which he makes his central empirical claim.

On the present: Hyperbolic dystopianism

Here is a sampling of what Deneen has to say about the present in the course of his 2018 introduction:

Nearly every one of the promises that were made by the architects and creators of liberalism has been shattered. (2)

The “limited government” of liberalism today would provoke jealousy and amazement from tyrants of old, who could only dream of such extensive capacities for surveillance and control of movement, finances, and even deeds and thoughts. The liberties that liberalism was brought into being to protect — individual rights of conscience, religion, association, speech, and self-governance — are extensively compromised by the expansion of government activity into every area of life. (7)

Our electoral process today appears more to be a Potemkin drama meant to convey the appearance of popular consent for a figure who will exercise incomparable arbitrary powers over domestic policy, international arrangements, and, especially, war-making. (8)

There has always been, and probably always will be, economic inequality, but few civilizations appear to have so extensively perfected the separation of winners from losers or created such a massive apparatus to winnow those who will succeed from those who will fail. (9)

Today’s liberals condemn a regime that once separated freeman from serf, master from slave, citizen from servant, but even as we have ascended to the summit of moral superiority over our benighted forebears by proclaiming everyone free, we have almost exclusively adopted the educational form that was reserved for those who were deprived of freedom. (13)

Already these early assertions tell us quite a bit about Deneen’s evaluative standards. First off, his condemnation of liberal democratic life is meant to be world-historical: things are about as bad now as they have ever been anywhere. Furthermore, Deneen situates contemporary America right down with the truly retrograde regimes when it comes to basic politics, economics, and education. Americans are worse off today in terms of basic freedoms than citizens were under the “tyrannies of old.” American elections are a farce, and the U.S. government today exerts “incomparable arbitrary” powers over its citizenry. Present-day America is more debased than almost any other civilization in terms of its economic inequalities. And our educational system approximates that which was formerly reserved for slaves and serfs. The hyperbole continues unabated through later chapters, where Deneen will allude, for example, to our “flattened cultural wasteland,” our “blighted cultural landscape,” and the “gathering wreckage of liberalism’s twilight years.”

I do not have an especially sunny view of American democracy. There are signs of corruption all around, and some of the problems that Deneen describes — concerning surveillance, executive power, technology, and inequality — strike me as altogether serious and real. But even granting all that, Deneen’s totalizing pessimism bespeaks, I think, a serious failure of judgment.

Between MAGA and the Middle Ages: Deneen’s romantic nostalgia

On Deneen’s adjudicatory scale, America today is about as bad as it gets. But what constitutes his positive standard? If liberalism has failed and America is so bad, has it ever been decent or good? Is there some clear ideal or good against which Deneen makes these extraordinary adjudications?

These seem like the kind of questions that a book like Deneen’s should answer clearly, but instead he is simply inconsistent. On the one hand, he concedes at the beginning of the book that liberalism has been a “wildly successful wager” (2), and insists throughout that there “there can be no return and no ‘restoration’” (18), that there is no “idyllic pre-liberal age” to which we might appeal or hope to return (184). On the other hand, the book is chock-full of vague nostalgia and idealistic appeals to the past. He speaks, for example, of how “the Roman and the medieval Christian philosophical traditions retained the Greek emphasis upon the cultivation of virtue” as a defense against tyranny, and of how ancient institutions sought to check individual power. He speaks of how the idea of individual rights and dignity originated in “pre-modern medieval Europe” (22), and of how in older times, each generation was taught to consult the “great works of our tradition, the epics, the great tragedies and comedies, the reflections of philosophers and theologians, the revealed word of God, the countless books that sought to teach us how to use our liberty well” (115). According to Deneen, these ancient and Christian influences used to play an important role in American life, until some point in the vague but not-so-distant past:

Americans for much of their history were Burkeans in practice, living in accordance with custom, basic morals, norms. You should respect authority, beginning with your parents. You should display modest and courteous comportment. You should avoid displays of lewdness or titillation. You should engage in sexual activity only when married. Once married, you should stay married. You should have children — generally, lots of them. You should live within your means. You should thank and worship the lord. You should pay respect to the elderly and remember and acknowledge your debts to the dead. (147)

Before the “collapse of the liberal arts” and the “redefinition of liberty” in this country, Americans lived according to discipline and self-control; they had more gratitude, wisdom, self-restraint, modesty, and honesty, as well as better norms of courtship (39). Deneen doesn’t deign to specify a timeframe for this charming epoch, but given his emphasis on sexual customs it seems fair to presume that the collapse happened in the 60s and the 70s — i.e., a period which also involved a massive expansion of education and civil rights in this country.

Deneen clearly prefers the ancient to the modern world, and America’s genteel past to its more democratized present. And though intellectually he surely recognizes that, for whole swaths of the population, the past wasn’t very rosy at all, he clearly yearns for those bygone days.

One result of Deneen’s wonky historical sense is that, in addition to the dystopianism, a vague and dislocated idealism pervades the book — an implicit high standard against which he condemns the present, but which he can’t satisfactorily find in the past, and so resolutely refuses to clarify.

Localism unbound: Deneen’s unaccountable future

This lack of concreteness and clarity — this romantic nostalgia and flight from reality — is also clearly manifest in Deneen’s proposed remedy for contemporary ailments. In some respects Deneen’s proposal is quite concrete and tangible: He calls for a retreat from individualism and national obsessions, and a renewed focus on local forms of community and communal practices. Channeling republican thinkers from ancient Greece to Tocqueville, Deneen invokes ideals of classical household economics, traditions of self-government and small-polis living, and a renewed attention to the ritualistic forms that shape most human cultures (“practices fostered in local settings, focused on the creation of new and viable cultures, economics grounded within virtuosity within households, and the creation of civic polis life”). All of this sounds fine, and it’s easy enough to imagine what he means: We should support local shops, engage in handiwork, make music together, join a church and the PTA. I have nothing much to say against this. I would love to see local forms of community, care, and connectedness flourish. It’s also worth noting that many people on the social justice and environmental left have been making this kind of appeal (and cultivating these kinds of changes) for decades.

The problem, as I see it, is that even while Deneen makes his case for localism, he simultaneously decries the idea of governance (reducing it to corrupt “liberalocratic” statism). Which is to say that the localist solution Deneen proposes in his book is quite weak and apolitical, and as such arguably not an especially realistic response to the problems of the day, which clearly require coordinated political action and civic engagement throughout various levels of government and society.

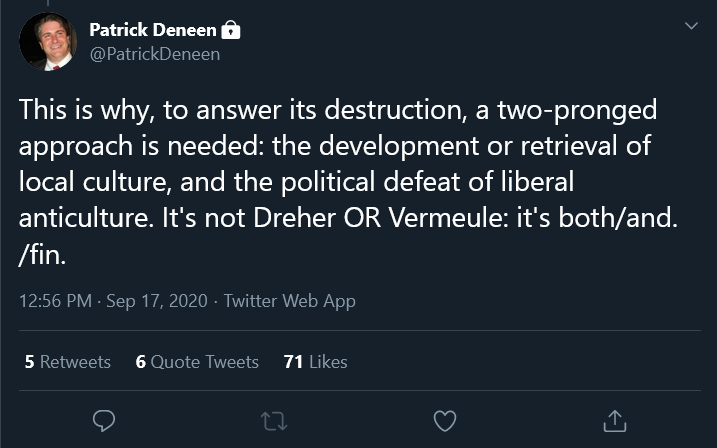

More recently, Deneen has all-but conceded this point in his work on Aristopopulism, and by acknowledging — at least on Twitter, in a since-deleted tweet — that localism needs to be part of a “two-pronged approach” that is supplemented by Adrian Vermeule’s big-state, heavy-handed illiberal constitutionalism (also known as integralism). This is a troubling development insofar as it is in obvious contradiction with Deneen’s own critique of Obama-style/Democratic statism: the despotic and tyrannical nature of the modern state constitutes a major part of Deneen’s despairing ideology (which I discuss at greater length in the next section), but clearly that critique only cuts in one direction. Furthermore, in Why Liberalism Failed, Deneen introduces the idea of local autocracies and theocracies, and then fails to reject the idea that this kind of local government overreach would be cause for concern:

Calls for restoration of culture and the liberal arts, restraints upon individualism and statism, and limits upon liberalism’s technology will no doubt prompt suspicious questions. Demands will be made for comprehensive assurances that inequalities and injustice arising from racial, sexual, and ethnic prejudice be preemptively forestalled and that local autocracies or theocracies be legally prevented. Such demands have always contributed to the extension of liberal hegemony, accompanied by simultaneous self-congratulation that we are freer and more equal than ever, even as we are more subject to the expansion of both the state and market, and less in control of our fate. (196-197)

This passage, tucked in towards the end of Deneen’s book, is a moment where we glimpse the radical character of Deneen’s anti-liberal critique. Deneen never does say much about what his kind of localism would mean in the context of actual American constitutional law, which aspires to strong protections against autocratic power and theocracy, and (at least in theory) protects citizens from local community overreach. Rather than clarifying this point, Deneen expresses a vague hope that new political theories will emerge out of new forms of community practice. It seems clear that he would rather see “local autocracies or theocracies” installed than admit that liberal government — including a large, democratically-empowered federal bureaucracy — is sometimes about more than raw, unaccountable power. And, again, it is striking that Deneen does not seem to have similar concerns about the integralist project.

Setting that contradiction aside, the basic point is that Deneen’s treatment of politics is just as confused as his definition of liberalism and his disjointed historical standards. As Samuel Goldman puts it in his review, “Even under post-liberal or post-modern conditions, however, we would still need some notion of how government ought to be set up.” This is, I think, a generous understatement. Deneen’s account of modern government is so cynical that it’s hard to see on what basis he would ever challenge someone like Trump, and he proffers a political theory that refuses to articulate any limits to (local) authorities.

Whereas notions like Fukuyama’s “end of history” can be a source of complacency and acquiescence, Deneen opens the door to a volatile and deeply unaccountable sort of political life.