With Build Back Better now on ice, the time has come for Child Tax Credit advocates — myself included — to accept an inconvenient truth: Joe Manchin is a sitting U.S. senator, and we are not.

Senator Manchin made his red lines for the monthly child benefit clear early in the process. He argues that unconditional payments to households with children risk discouraging work. And with no strings attached, he worries that non-working parents will misuse the credit on drugs or alcohol.

To date, Child Tax Credit (CTC) advocates have responded with a mix of persuasion and ridicule. The Niskanen Center has published reports explaining why child benefits don’t disincentivize work and may even reduce spending on temptation goods due to lessened financial stress. Others, meanwhile, maligned Senator Manchin as heartless or dishonest — an unproductive approach under the best of circumstances.

The all-or-nothing approach to the CTC is perplexing for a proposal that was barely on the radar as little as five years ago and only embraced by Biden at the tail end of his presidential campaign. It is worth stepping back to appreciate how far the concept of a child allowance has come in that short time and why Manchin isn’t unreasonable for failing to keep pace with the current vogue in social policy. Indeed, a CTC compromise that would have been unthinkably ambitious only a few years ago is still well within reach.

Taking Manchin seriously

Consider Manchin’s dual demands for a work requirement and making access to the credit easier for children raised by their grandparents. These goals are in obvious tension on the surface, as many grandparents are retired and therefore not working. Yet there are ways to square this circle. For example, grandparents and other caregivers on fixed incomes could become eligible for the full credit even if the CTC retained a modest earnings test for able-bodied parents of working age.

Manchin’s seemingly incompatible requests make more sense with added context. Of the grandparents in West Virginia who live with their grandchildren, 54 percent are the primary guardian or caregiver — the second-highest rate in the country and a disturbing byproduct of the opioid epidemic sweeping the state. Opioid deaths in West Virginia increased 62 percent between April 2020 and April 2021, well above the national average. While the notion that some fraction of non-working parents may spend their child benefit on fentanyl or methamphetamine may sound patronizing and cruel, Manchin’s red lines reflect a good-faith concern informed by the facts on the ground in his own state. Studies about how families spend child benefits on average don’t truly address the issue.

My view is that an earnings test of any kind will be unnecessarily cumbersome to administer. But at risk of repeating myself, my personal opinion is worth precisely nothing when it comes time for the Senate to vote. Considering that the alternative is no CTC expansion whatsoever, anti-poverty and pro-family advocates have every reason to meet Manchin in the middle.

It’s time to get creative

With some creativity, a modified CTC expansion can achieve most of its hoped-for anti-poverty impact while accommodating Manchin’s core concerns. However, breaking the negotiating impasse will require more than a split-the-difference compromise. Each side must sacrifice something in a way that legitimately addresses the other’s concerns while still saving face.

Here’s how that might look in practice:

- Preserve the monthly child allowance for young children.

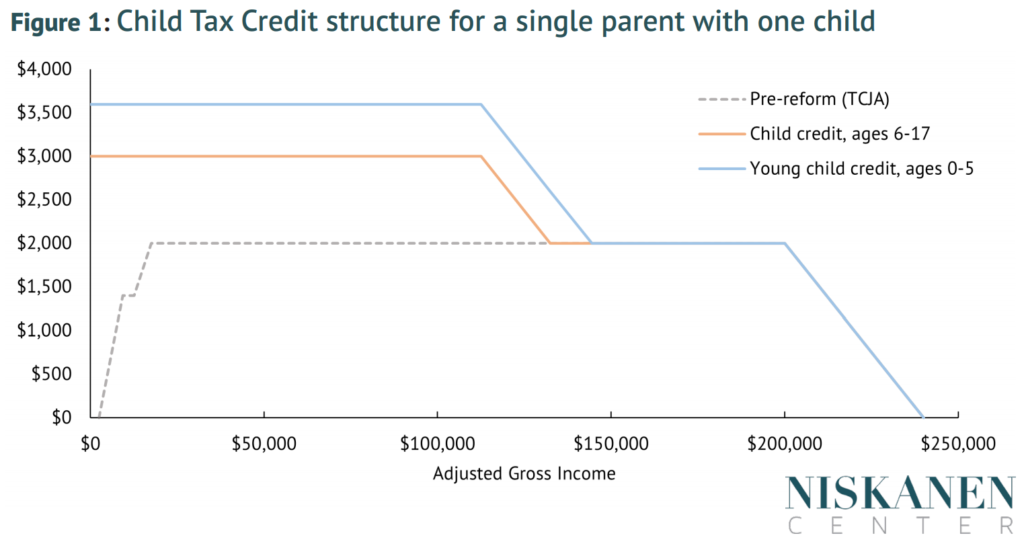

A strong compromise proposal would preserve the larger credit size for children below the age of 6 and its structure as an unconditional monthly payment. New parents face different work and family obligations than parents of school-aged children, and even some Republicans have proposed fully-refundable tax credits for parents of infants. A monthly child benefit is most useful in these early years of a child’s development, when parental income is also typically at its most volatile. A monthly but more targeted benefit would also give the IRS the policy continuity it needs to invest in child benefit administration.

- Restore a work test for the CTC claimed on behalf of older kids, but with exemptions.

A work test for claiming the CTC for kids ages 6 to 17 could be set up in one of two ways. Either the credits could phase in with earnings as they have in the past, if at a faster rate, or nonfilers could be required to submit proof of employment when they apply. Manchin has suggested adding a binary “do you have a W2” test that would represent an extraordinarily light work requirement in the big picture. Importantly, retired parents, disabled parents, and full-time students should be exempt from any work test to focus on the able-bodied, working-age population that most concerns Manchin.

- Lower the CTC’s phase-out threshold without creating a benefit cliff.

Lastly, Manchin has stated that he wants the expanded CTC to include an “income cap” of $60,000. This would produce a sharp benefit cliff in the credit while exacerbating marriage penalties in the tax code if taken too literally. A more charitable interpretation is that Manchin simply wants the CTC to be more tightly means-tested by lowering the income thresholds at which the credit begins to phase out.

The expanded CTC currently begins phasing-out at a rate of 5 percent for incomes above $75,000 for single filers, $112,500 for heads of household, and $150,000 for joint filers. While I have argued that there are benefits to a relatively universal program structure, lowering the threshold is an easy change to accommodate. For example, Canada’s child benefit begins phasing out at incomes above $30,000, but at a relatively slow rate that avoids creating high implicit marginal taxes while extending benefits well into the middle-class.

A “second-best” reform

The precise parameters of a compromise reform are ultimately up to Congress. Nevertheless, the above framework offers a set of design principles that balance good policy with realistic politics, letting each side claim partial victory. Despite some sacrifices, it would remain one of the most progressive anti-poverty reforms in a generation.

Unfortunately, these and other potential middle-ground options have not been broached. Instead, the strategy has been to hold the line, call Manchin’s bluff, and mount a pressure campaign that has only strengthened his centrist reputation.

In short, advocates took Manchin literally without taking him seriously. That strategy failed. Whatever the “first-best” CTC reform, politics remains the art of the possible. Or as economist Dani Rodrik puts it, “politics is second best, at best.” It’s now on Senate Democrats to meet with Manchin and, together, design the second-best damn CTC expansion they possibly can.

Photo Credit: iStock