The economic woes of the U.S. coal industry precede COVID-19. Coal plants were already shutting down at near-unprecedented levels, and almost half of the operating fleet was selling power at a loss. As the coronavirus-triggered shutdown rattles the U.S. economy, declining electricity demand and lower electricity prices make it even more likely that utility companies will have to retire uneconomic coal plants before the end of their useful lives. This will lead to billions of dollars of unrecovered plant capital investment.

In states with deregulated electricity markets, an uneconomic coal plant usually becomes a “stranded asset”–meaning, that it shuts down before the end of its useful life (which for accounting purposes is roughly 46 years), and companies must write off the plant’s remaining value. Investors may not be pleased about absorbing the capital losses from retiring an uneconomic coal plant.Still, it is better than absorbing both operational and capital losses from continuing to operate the plant.

However, in rate-regulated markets, where utilities receive regulatory assurances of cost recovery, the costs of retiring uneconomic coal plants are passed onto ratepayers. One way to do this is to pay off the debt on the plant ahead of schedule, and raise rates to cover the change. Another approach is to idle the plant but let rates, and debt payments, continue as if it is still operating (in the jargon, the plant then becomes a “regulatory asset,” rather than a real asset). Sometimes, the two are combined. To avoid the conversation about any unrecovered capital, uneconomic coal plants continue to be operated, a practice that is estimated to have cost ratepayers in regulated markets $3.5 billion between 2015 and 2017. Putting customers on the hook to pay the outstanding balance on these uneconomic assets is hampering the shift to cleaner energy because customers would have to pay for both shutting down the older generation and replacing it with new, cleaner plants. With a recession looming, environmental and consumer advocates, utilities, and state legislatures must think of innovative ways to allow for the retirement of coal plants before the end of their useful lives without forcing ratepayers to shoulder the cost of these stranded assets.

Accelerating coal retirements through securitization

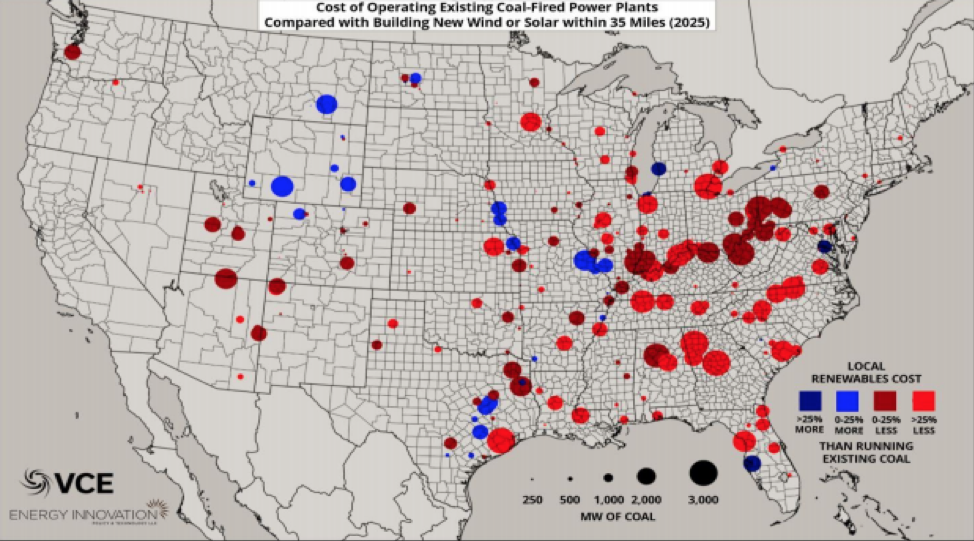

In 2017, the Carbon Tracker Initiative found that regulated utilities are carrying $185 billion in potential stranded assets in uneconomic coal units. As the cost of alternative energy sources, and the market value of coal plants, continues to fall, that debt will only rise. As depicted in the figure above, this issue is especially pronounced in the southeastern part of the U.S., where a majority of coal plants are at significant risk of being replaced by cheaper solar by 2025. A report published by Energy Innovation and Vibrant Clean Energy found that North Carolina, Florida, Georgia, and Tennessee — all regulated electricity markets — have the highest projections for coal plants being substantially at risk of replacement with cheaper renewables by 2025. These states must be able to incorporate these cheaper and cleaner resources, without placing an undue burden on their ratepayers to pay down the debt of utility companies.

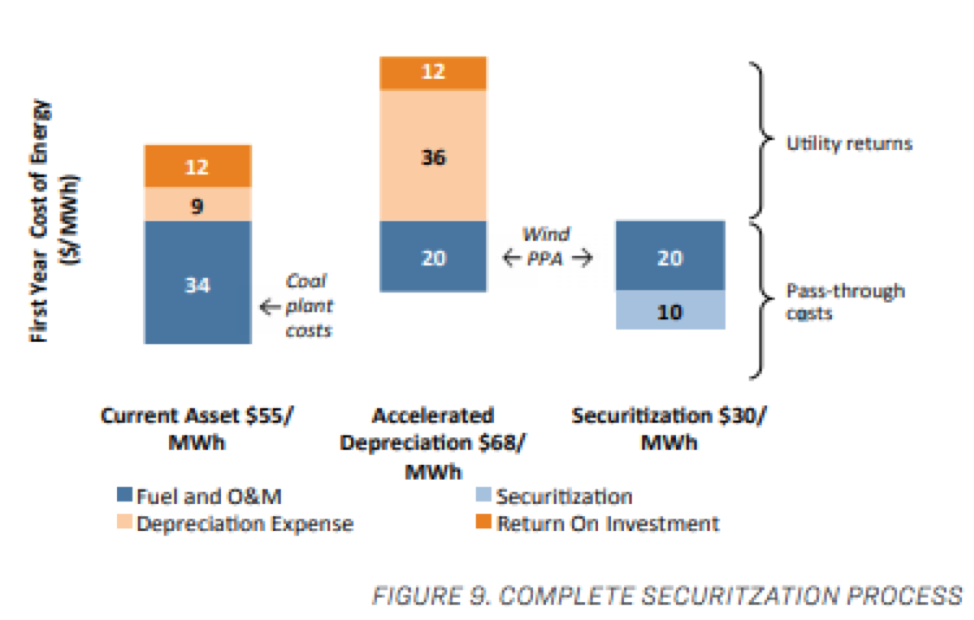

A recent joint report published by the Sierra Club and the Rocky Mountain Institute explored innovative financial mechanisms that could address the challenges of accelerating uneconomic coal plant retirements and enable the transition to cleaner and more economically efficient generating sources. One financial tool the report suggests is securitization — refinancing higher-cost debt or equity with low-interest, ratepayer-backed bonds. Such bonds are secured by a stream of expected future ratepayer revenue. They offer an alternative way to address the near-term financing needs of owners of noneconomic generation while also minimizing ratepayer impacts. Rather than customers paying the utility the full cost of providing service, plus a rate of return on investments, ratepayer-backed securitization allows utilities to issue a bond that ratepayers will pay the interest (and eventually the principal) on via a bill surcharge. The funds raised by the bond are then used to cover the utility’s stranded-asset losses. For ratepayers, the cost of paying off the bond is less than the cost of operating the coal plant.

Securitization can create immediate and long-term savings for ratepayers, which are badly needed during this financial downturn. Savings are created for two reasons. First coal-fired power plants are expensive to operate, and their continued use has crowded out cheaper and cleaner alternatives. As Joseph Daniel reports, in “four coal-heavy energy markets, coal-fired power plants incurred $4.6 billion in market losses over the past three years”, and continuing business as usual in these markets “places at least a $1 billion burden on ratepayers each year.” Closing these coal plants will provide immediate relief to taxpayers from fuel and other operational expenses. Second, ratepayer-backed bonds have a AAA rating, which reduces interest rates to around 3 percent to 4 percent, a bargain for utilities that face a 6 percent to 8 percent interest rate for conventional debt. Essentially, you are lowering a utility’s borrowing costs, which in turn reduce the amount of money ratepayers will have to repay.

While securitization offers an opportunity to retire costly and carbon-intensive generating sources, pay back investors, and reduce ratepayer costs, it can also be used to fund transition assistance for workers and communities affected by plant retirements. An analysis by Uday Varadarajan, lead author of the Sierra Club report, of possible Minnesota coal plant closures found that securitized 20-year bonds would create $45 million of savings, relative to accelerated depreciation over five years or a regulatory asset approach. Using 15 percent of these savings for transition assistance, as pending securitization legislation in Colorado proposes, would yield around $7 million for workers and communities impacted by these retirements. This type of transition assistance could pay two-thirds of the median salary of 25 power plant operators for five years. Additionally, the amount of transition assistance from securitization made available increases with the net plant balance and the remaining life of the asset, meaning the transition assistance amount is automatically scaled up to the size of the shock that a given community faces from transition.

Enabling securitization through stimulus

It will probably be quite some time before Congress has any appetite to enact additional stimulus spending. Still, when it comes, legislators will have an opportunity to incentivize state public utility commissions to support securitization bills. Although most of the policy formation will be done at the state level, the Rocky Mountain Institute has suggested that the next stimulus package enables the U.S. Department of Energy to issue loan guarantees to support ratepayer-backed securitization in states.

Title XVII of the Energy Policy Act of 2005 already gives DOE the authority to issue loan guarantees for innovative projects that reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Congress should expand the scope of the Title XVII loan program to support innovative financial mechanisms that reduce power sector GHG emissions. The DOE loan guarantee would make the already comparatively cheap ratepayer-backed bonds even cheaper; the federal guarantee allows the bonds to pay less than the 3-4 percent they would be otherwise be paying. A report by Standard & Poor’s compared the interest rates of different asset classes and found the interest rate of the ratepayer-backed bond, to be lower than utility bonds, but not as low as bonds backed by government agencies. Thus, having a DOE loan guarantee could create even more savings for ratepayers, give investors the confidence that they will recoup their investment, and allow utilities to raise low-cost debt to meet near-term financing needs.

While U.S. power generators continue to assess the total implications of COVID-19 on the electricity market, it is likely that the pandemic will only increase the economic woes and, therefore, spur the retirement of coal plants across the country. If this is the case, coal-heavy utilities should seriously consider securitization as a way to recoup unrecovered power plant debt and create short-term savings for ratepayers, all while putting the U.S. electricity market on a path of low-carbon recovery. Federal policymakers could help them.

Photo by Michal Matlon on Unsplash