The Trump administration is continuing its overhaul of federal pollution restrictions by rolling back Obama-era strictures on coal-burning power plants. The EPA’s proposed Affordable Clean Energy Rule (ACE) would effectively repeal and replace Obama’s Clean Power Plan (CPP) and comes just weeks after the EPA released its plans to freeze fuel economy standards. The ACE rule establishes guidelines for states to use when developing plans to limit greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions at their power plants and defines “the best system of emission reductions” as on-site heat-rate improvements (HRI), which is a policy option to reduce the amount of heat required to produce one kilowatt-hour of electricity. The proposed rule also takes aim at the New Source Review program, which requires power plant operators to undergo EPA preconstruction reviews when they propose modifications to existing facilities that would result in a significant increase in a regulated pollutant.

It should come as no surprise that these modest guidelines and the loosening of the New Source Review program will be seen as a lifeline to the coal industry, with some arguing the changes will lead to an increase in greenhouse gas emissions over the course of a year. By rolling back regulations for transportation and now the power sector, the two largest contributors of carbon emissions, the Trump administration has shown little regard for the costs associated with climate change.

What is arguably of greater concern, however, is the effect of forgoing the ancillary cobenefits that would be achieved alongside deeper reductions in GHG emissions, such as reductions in nontargeted pollutants improving air quality and public health. Most notably, reductions in CO2 emissions result in lower concentrations of PM2.5, a pollutant with well-documented health and environmental impacts.

A review of the cobenefits literature and the monetized net benefits of a range of climate-related policies will help to put the impact of the ACE rule in context.

Cobenefits of HRI and CPP

The health cobenefits of climate policies are well-studied. I’ve previously written about an analysis of three separate policy scenarios. It demonstrated that less stringent climate policies, such as the proposed ACE rule, have significantly fewer cobenefits than more stringent policies such as the Clean Power Plan it will replace (let alone a meaningful carbon tax scheme). That Harvard-Syracuse study found that if coal-fired plants were to achieve heat-rate improvements similar to the ones being proposed in the ACE rule, the result would be a modest increase in average annual PM2.5 and peak ground-level ozone concentrations, resulting in a slight increase in premature deaths from heart attacks relative to the reference case. The reference case uses energy demand projections from the Annual Energy Outlook for 2013, and assumes EPA clean-air policies are fully implemented but not changed (either with Obama’s CPP or with ACE). The study concluded that heat-rate improvements would result in an additional 10 premature deaths per year, as coal-fired plants would work more efficiently but also increase their output. By contrast, it found that over 3,000 premature deaths could be avoided with a carbon tax or CPP policy.

The realized benefits of decreased air pollution are mainly decreases in premature deaths, fewer heart attacks, and fewer hospital admissions for cardiovascular and respiratory issues. The authors of the Harvard-Syracuse study monetized the cobenefits associated with the policy scenario that mimicked the Clean Power Plan. Their analysis found that most counties in the United States gained at least $1 million in annual cobenefits from improved air quality within the implementation year of the policy, and that the value of health cobenefits alone would exceed the costs of the policy in all regions of the country but the Pacific Northwest by 2030.

Climate and Health Cobenefits of ACE

As the Harvard-Syracuse study demonstrated, less stringent heat-rate improvements, similar to the ones in the ACE rule, achieve the smallest amount of cobenefits and would lead to an increase in premature deaths per year. In fact, the results of the Harvard-Syracuse study parallel the findings in the EPA’s own Regulatory Impact Analysis of the ACE rule. The EPA’s own models predict that the heat-rate improvements in ACE would significantly increase emissions of CO2 , sulfur dioxide,, and nitrogen oxides when compared to the base case of the Clean Power Plan, and would decrease those pollutants modestly relative to no CPP at all.

The proposed rule presents several different pathways states could choose to regulate coal-fired power plants. Under the pathway that the EPA considers most likely, the agency estimates that increases in PM2.5 alone will result in as many as 1,400 premature deaths annually by 2030, and up to 16,000 new cases of upper-respiratory problems.

The impact analysis of the ACE rule includes a section that monetizes the climate benefits and health cobenefits of the proposal. Climate benefits are the direct effects on global warming of reducing CO2, while the health cobenefits are the result of indirect reductions in nontargeted pollutants via reductions in CO2. The analysis reports negative values, which represent forgone benefits, in parentheses. Positive values represent benefits realized by the policy.

Source: Regulatory Impact Analysis for the ACE rule

The table shows the monetized benefits realized under the ACE proposal when compared to the base case of the Clean Power Plan. All estimated benefits are negative, indicating that each of the policy scenarios yield forgone climate benefits, as well as forgone ancillary health cobenefits.

Although total monetary values of the climate and health cobenefits of the ACE rule may be negative, an understanding of the net benefits of the policy is more telling, as it allows policymakers to understand how the monetary benefits compare to the compliance costs of the proposal. The analysis predicts that the ACE rule will have positive net benefits of up to $3.4 billion per year between 2023-2037 when compared to the Clean Power Plan, and $2 billion relative to the no-CPP, alternative baseline. However, this finding of positive net benefits applies in only one of the three HRI policies that the ACE rule proposes, and only accounts for the domestic climate benefits achieved through reductions in the targeted pollutant (CO2). Including the impacts that the ACE rule will have on health cobenefits significantly changes the net benefits that the proposed policy is expected to deliver.

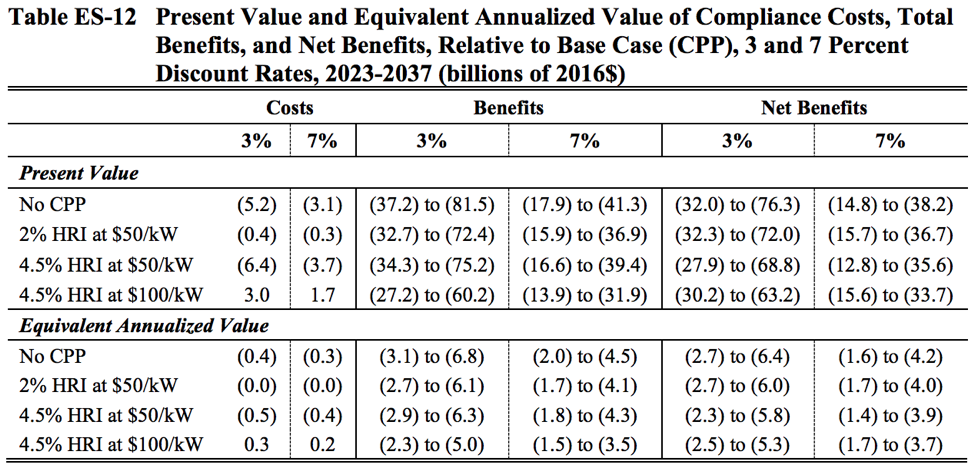

Source: Regulatory Impact Analysis of ACE Rule

The table above represents the present value, as well as the equivalent annualized value, of the estimated costs, benefits, and net benefits, inclusive of ancillary health cobenefits, relative to the base case of the CPP. In this analysis, the net benefits of every policy scenario proposed by the ACE rule are negative.

Maximizing Cobenefits Through Flexibility and Accountability

The weak emissions reductions suggested by the ACE rule will do almost nothing to stem CO2 emissions. The EPA’s own assessment of the ACE rule suggest that the increases in premature deaths, the serious health impacts, and the negative welfare costs to society make it a hard policy to defend. The inclusion of monetized cobenefits in their policy analysis demonstrates that simply reducing compliance costs will not translate to welfare gains for the overall society.

The hesitation about enacting stringent climate policy is due to the fact that the economic costs of deep CO2 reductions are borne immediately, while the benefits are uncertain and accrue for generations to come. However, accounting for the health cobenefits when analyzing climate policy justifies immediate and meaningful reductions of CO2. These health cobenefits are widespread and can immediately improve the well-being of communities who bear the costs of climate action. They should be counted against the costs of environmental regulation or carbon pricing. Incorporating these health cobenefits into policy impact analysis is necessary in order to truly account for the costs and benefits of climate action.