The humanitarian case for legal status for undocumented immigrants is strengthened this week by new research published in Science that protections from deportation can lead to concrete, measurable, and significant improvements in the mental health of children. Here’s the abstract:

The United States is embroiled in a debate about whether to protect or deport its estimated 11 million unauthorized immigrants, but the fact that these immigrants are also parents to more than 4 million U.S.-born children is often overlooked. We provide causal evidence of the impact of parents’ unauthorized immigration status on the health of their U.S. citizen children. The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program granted temporary protection from deportation to more than 780,000 unauthorized immigrants. We used Medicaid claims data from Oregon and exploited the quasi-random assignment of DACA eligibility among mothers with birthdates close to the DACA age qualification cutoff. Mothers’ DACA eligibility significantly decreased adjustment and anxiety disorder diagnoses among their children. Parents’ unauthorized status is thus a substantial barrier to normal child development and perpetuates health inequalities through the intergenerational transmission of disadvantage.

The paper is “Protecting unauthorized immigrant mothers improves their children’s mental health” by Jens Hainmueller, Duncan Lawrence, Linna Martén, Bernard Black, Lucila Figueroa, Michael Hotard, Tomás R. Jiménez, Fernando Mendoza, Maria I. Rodriguez, Jonas J. Swartz, and David D. Laitin. It’s available here.

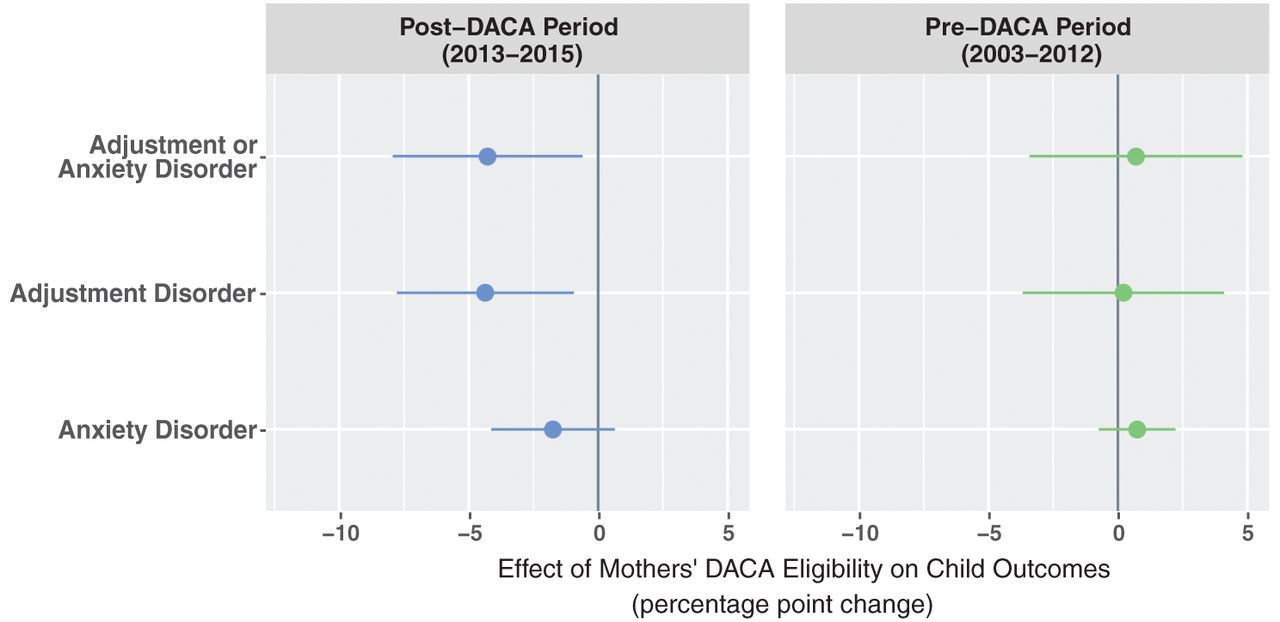

The magnitudes of the effects are surprisingly big:

Among children with DACA-eligible (by age) mothers 7.8% were diagnosed with adjustment or anxiety disorders before DACA. When DACA went into effect, that number dropped by 4.5 percentage points to only 3.3% when DACA went into effect. That’s more than a 50% change in the rate of the disorders.

This is not the first research that shows that a parent’s undocumented status can have a negative effect on the mental health of children. It is not a big leap to conclude from that research that protections—even temporary protections that do not change an immigrant’s legal status—may confer mental health benefits. But this new paper is, to my knowledge, the first research that demonstrates that the DACA protections actually have conferred measurable benefits and that quantifies some of those benefits.

Supporters of “America First” policies are usually more likely to be persuaded by the economic benefits of deportation protections than the humanitarian case, since recipients of such protections are not U.S. citizens. But their kids are often U.S. citizens. All of the kids in this paper’s sample are U.S. citizens. Protecting their mental health doubtlessly puts the interests of America first.