This piece is part of a larger series on how immigration can help relieve U.S. labor shortages. You can explore the full series here.

As detailed in the first piece of this series, the U.S. is experiencing labor shortages in industries across the economy. The shortages manifest in tangible, negative impacts on Americans’ daily life and overall standard of living. This second entry of the series will delve into why these shortages cannot be filled by the current supply of domestic labor and explore what role immigration can help with the labor shortages domestic workers can’t fill.

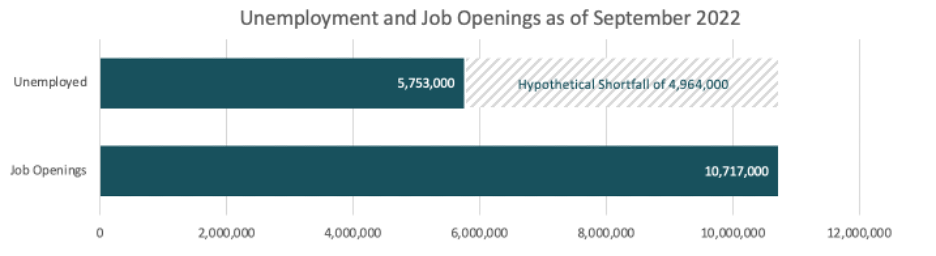

As of September 2022, there were over 10.7 million job openings in the United States. In the same month, there were approximately 5.8 million unemployed workers. This means that even if every unemployed individual’s skills, interests, and location perfectly aligned with the requirements of the open jobs, the U.S. would still have nearly 5 million unfilled openings.

Of course, this hypothetically perfect alignment of unemployed workers to job openings does not always manifest in reality. This is exemplified by how employers must compete for limited numbers of Americans with particular educational credentials or sought-after skill sets. Employees’ preferences also play a role as they evolve to prioritize remote work or other flexible working arrangements.

This gap has been growing for quite some time. From 2011 to 2021, monthly job openings increased by an average of 12 percent per year, from just over 3.4 million in 2011 to over 9.8 million in 2021. During the same period, however, the working-age population only increased an average of 0.3 percent per year.

As the size of our population has failed to keep pace with growth in demand, the share of the domestic workforce with the skills required to drive American innovation has also fallen short of the market’s needs. In 2019, foreign nationals represented 82 percent of full-time graduate students in petroleum engineering, 74 percent in electrical engineering, 72 percent in computer and information sciences, and 71 percent in industrial and manufacturing engineering. These graduate programs supply the talent needed to manage our energy stores, build technology, and maintain national security. However, if international students do not have a viable, long-term visa pathway, most graduates with these skills will be unable to stay and work in the U.S permanently and help with these labor shortages in jobs unfilled by domestic workers.

This pattern of skill mismatch (coupled with slow population growth) has plagued our labor market for years. Still, the labor shortages were even further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. It triggered the retirement of 2.6 million more workers than expected, with older and more susceptible workers choosing to exit the workforce prematurely to avoid illness. Several industries– including education, hospitality, manufacturing, and health care–now in urgent need of labor had some of the highest rates of workers reporting early retirement plans. What’s more, many individuals laid off early in the pandemic did not rush back to the workforce for a range of reasons, including vaccine requirements, fears of contracting illness, long covid, or a desire to change career direction.

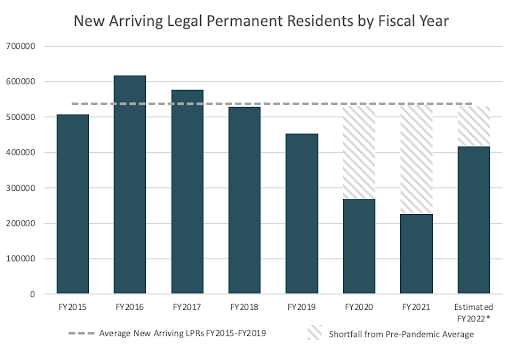

Immigration also notably factors into the labor market shortage. Immigrants participate in the labor market at a similar or higher rate compared to native-born Americans. During the pandemic, however, the U.S. experienced a sharp decline in both temporary and permanent immigration thanks to travel restrictions and administrative delays.

In the five fiscal years before the pandemic, the U.S. welcomed an average of approximately 540,000 newly arriving legal permanent residents (or green card holders) every year. In FY2020 and FY2021, that average dropped to less than 250,000. FY2022 demonstrated significant growth but failed to compensate for the losses of the previous two years. Based on pre-pandemic trends, we estimate that the U.S. is now nearly 700,000 new residents short of what it would have been had the pandemic not occurred, in addition to declines in temporary immigration that would help with the labor shortages domestic workers can’t fulfill.

Compounded by the incongruencies between the domestic workforce’s size and skill set and our labor demand, these missing immigrants have contributed to the shortages that we experience today. Therefore, augmenting our immigrant workforce could help relieve those shortages and bolster our economy.

Immigrants already fill important gaps in our labor market by working in occupations that Americans find less desirable and supplementing the small pool of Americans who currently graduate with the requisite skills in key industries. Immigrants are more responsive to labor needs than native-born workers and are more internally mobile, able to relocate to areas where the labor need is highest. Visa requirements often ensure that immigrants rebound rapidly in times of job loss. And because they did not have the same access to unemployment benefits, immigrants returned to work faster than their native-born counterparts during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Immigrants play a crucial role in our labor market, and the shortages Americans are experiencing today are, in part, the consequence of declines in legal immigration generated by the pandemic. Compensating for those downturns and restoring the population of immigrants to pre-pandemic levels could be a crucial step toward meeting those needs.