Federalism and Social Assistance

American fiscal federalism is ready for reform. We have seen recent changes to health policy and tax policy but the COVID-19 crisis has brought renewed attention to the role of social policy within American federalism. States were largely left unprepared when unemployment spiked. The federal government cobbled together a response largely outside of state administrative infrastructure. This situation was not inevitable.

Historically, states have been responsible for social assistance or income support programs. Federal support was introduced with the Social Security Act of 1935 and continues evolving through the present day. Social assistance programs can be broken down into three broad categories of beneficiaries with varying levels of federal support.

- The elderly and disabled receive assistance through Supplemental Security Income (SSI). It was introduced in 1972, replacing existing state programs funded with federal matching grants, as a wholly federal program.

- Able-bodied parents caring for children receive assistance through Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF). It was introduced in 1996, replacing existing state programs funded with federal matching grants, as a block grant program.

- Able-bodied adults without dependents receive assistance through a patchwork of state General Assistance (GA) programs. They are wholly state-funded and have never been eligible for federal funding.

The latter two programs, both aimed at able-bodied adults with and without dependents, are the focus of this brief. Federal support for these programs suffers from two major shortcomings related to their level and allocation.

Problem #1: Inadequate Funding

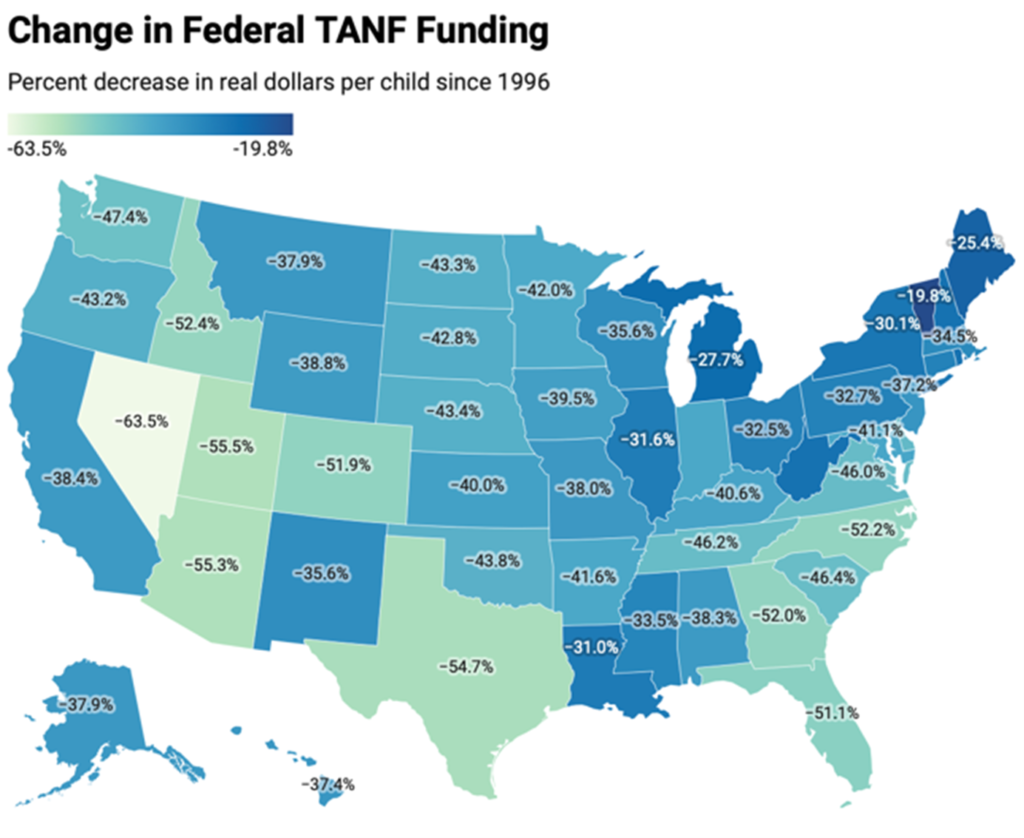

Federal support is inadequate and leaves states bearing too much of the fiscal burden. The initial value of the TANF block grant, when introduced in 1996, was substantially more generous than it is today. Because the total value of the $16.5 billion grant was not indexed for inflation or population growth, it has been subject to substantial erosion over the last 25 years. The total value remains $16.5 billion today. If it had been properly adjusted to keep pace with inflation and population growth, it would be $26.9 billion today. This amounts to a 42 percent decline in the real value of the grant for states. Population shifts have resulted in some states seeing larger declines than others (see Figure 1). The loss of support has translated into a decline in both benefit levels, and program reach across states over time.

GA’s fiscal outlook is exponentially worse as these programs have never been eligible for federal funding. Increasing fiscal pressures on states have resulted in a rapid decline in the number of states covering able-bodied adults. Whereas half of all states had such a program in 1989, only eleven state programs remain today. Moreover, states that have kept their programs have allowed benefit levels to erode over time.

Problem #2: Inequitable Allocation

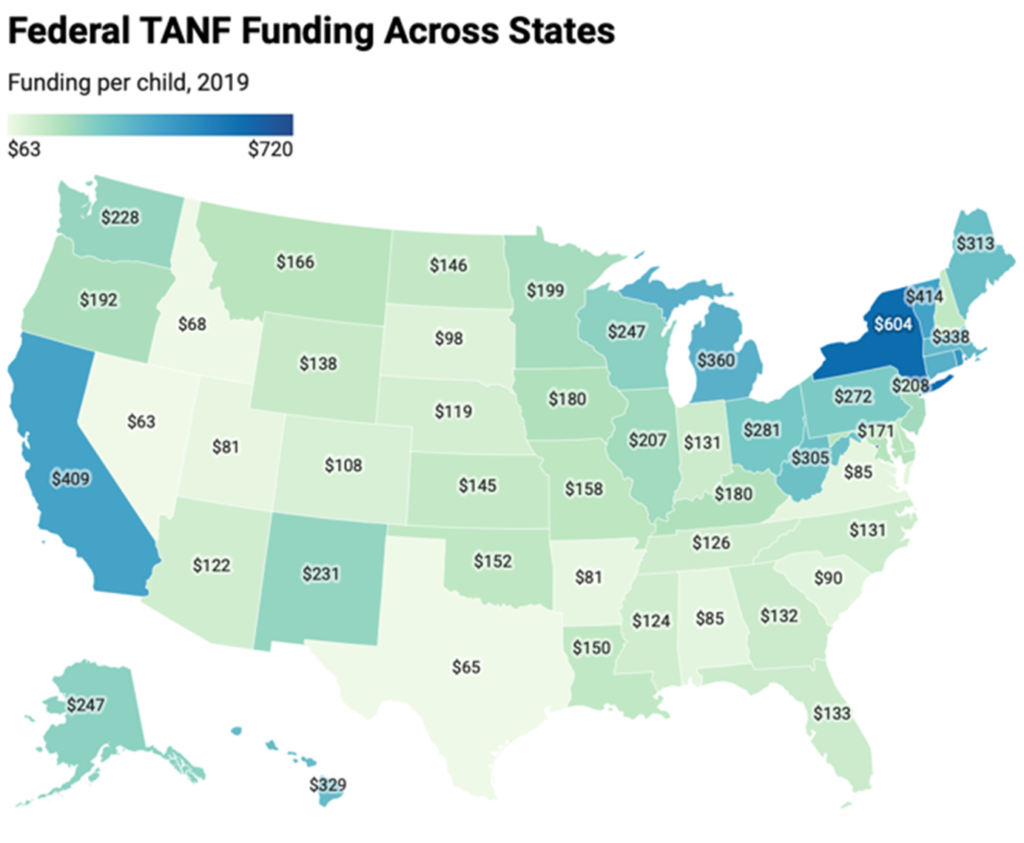

Existing allocation is enormously inequitable. Rather than base funding on fiscal capacity or population, the TANF block grant formula as it exists today is an anachronism of the old system it replaced. The previous system of matching grants used the FMAP matching formula, which favored wealthy states over poor states. When it was converted into a block grant in 1996, policymakers simply froze existing federal funding allocation. This had the effect of locking in previously existing inequities. The new law meant that the best-funded state (NY) received more than six times the funding per child as the worst-funded state (AL) as a block grant rather than a matching grant.

Differential growth in the population under 18 across states has exacerbated these inequities. Because the TANF block grant is allocated on a per state rather than per capita basis, states like Nevada (65 percent increase in population under 18) have had to do more with less while states like Vermont (25 percent decrease in population under 18) saw a rise nominal funding per child. The best-funded state now receives more than nine times as much as the worst-funded state (see Figure 2).

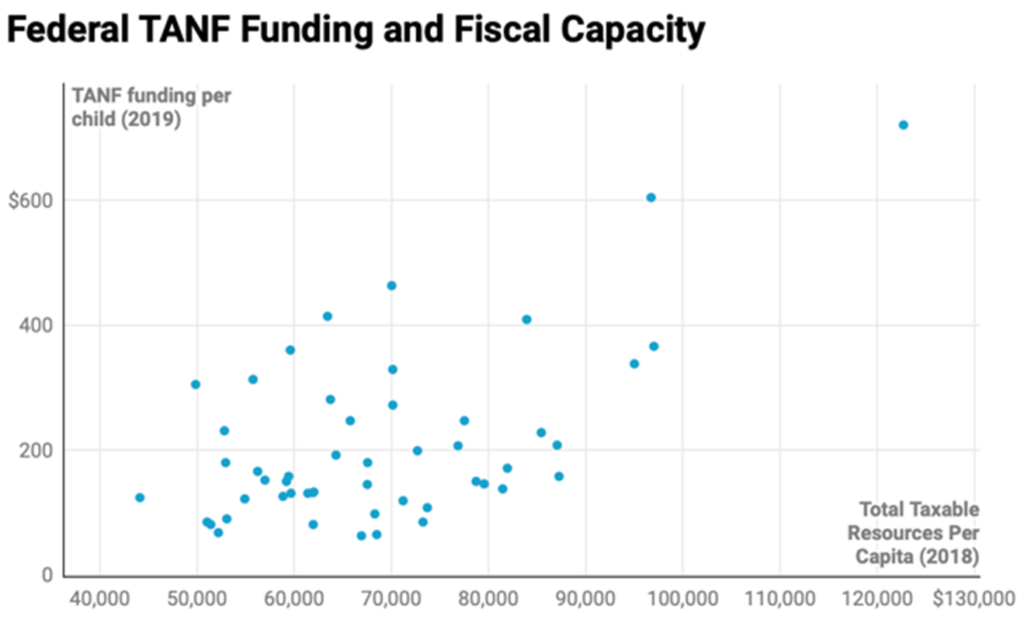

Most alarmingly, federal funding is positively correlated with fiscal capacity. The states with the greatest ability to fund social assistance programs receive the most, while the states with limited ability to fund them receive the least (see Figure 3). This is the exact opposite of what might be expected of a progressive system of fiscal federalism.

State GA programs face similar issues of inequity despite the total absence of federal funding. Program funding hinges entirely on state fiscal capacity. For example, it is unreasonable to expect Mississippi to support a GA program on top of all its present responsibilities when it has less than half the fiscal capacity of states like Massachusetts. Some minimal level of federal support is necessary to ensure states can fund the most basic GA program.

What about the SALT Deduction?

It has become fashionable to frame the state and local tax (SALT) deduction as a viable substitute for direct federal support for states. Evidence that the SALT deduction subsidizes state and local spending is scarce. Even if that was the case, it faces the same inequity issues discussed above insofar as it is regressive by rewarding states with the highest fiscal capacity the most and those with the lowest fiscal capacity the least. It is better to describe the SALT deduction (as we typically do the mortgage interest deduction) as a $21.1 billion tax break primarily for upper income households in wealthy states.

Comparative evidence from Canada, which has never had a similar SALT deduction, reveals that indirect support for states is no substitute for direct support.

Canadian Federalism: A Case Study

The history of federal support for provincial social assistance programs looks surprisingly similar to the American trajectory in many respects, with some important differences. Initially, Canada was a laggard relative to the United States. Whereas the U.S. introduced federal matching grants for families with children, the elderly, and the disabled in 1935, Canada did not do so until 1966 with the introduction of the Canada Assistance Plan (CAP). The CAP was a 50/50 matching grant for provincial social assistance programs covering all non-elderly persons.

In 1996, Canada converted CAP into a block grant, renamed the Canada Health and Social Transfer (CHST), which combined funding for provincial health, higher education, and social assistance programs. The portion that funds social assistance, higher education, and social services was subsequently split off into a distinct block grant called the Canada Social Transfer (CST) in 2004.

Beyond similarities in timing and the shift from matching to block grants, the CHST/CST had two important characteristics that make them unique and highly successful. First, funding is provided to each province on an equal per capita basis, irrespective of what each province received under the old matching formula. Second, the amounts are legislated to grow at a rate of 3% each year, effectively ensuring that inflation does not erode their real value.

The relative stability of benefit levels and the reach of social assistance across provinces since 1996 demonstrate that, contra common American perceptions, conversion to block grants is not necessarily a death knell for state programs as long as they are structured appropriately.

A Better Way to Support States

The current system of federal support for state social assistance programs is broken. A better way forward would drop the worst aspects of existing American arrangements and adopt the best aspects of Canada’s system. In principle, this includes

- Eliminating the SALT deduction;

- Using those revenues to increase total funding to states for social assistance programs;

- Introducing federal support for general assistance programs;

- Allocating that funding to states on an equal per capita basis;

- Indexing per capita amounts for inflation.

We can achieve this by repealing the SALT deduction and TANF block grant and replacing them with a larger and simplified Social Assistance Block Grant (SABG).

The combined value of the SALT deduction ($21.1 billion) and TANF block grant ($16.5 billion) provides about $37.6 billion in potential funding to provide states with fiscal relief. Since SSI already covers low-income elderly beneficiaries, the relevant target population includes individuals under age 65. It makes sense to allocate grants on a 0-64 years old per capita basis. Within a deficit-neutral framework, this amounts to a grant of $131 per capita (0-64) to each state.

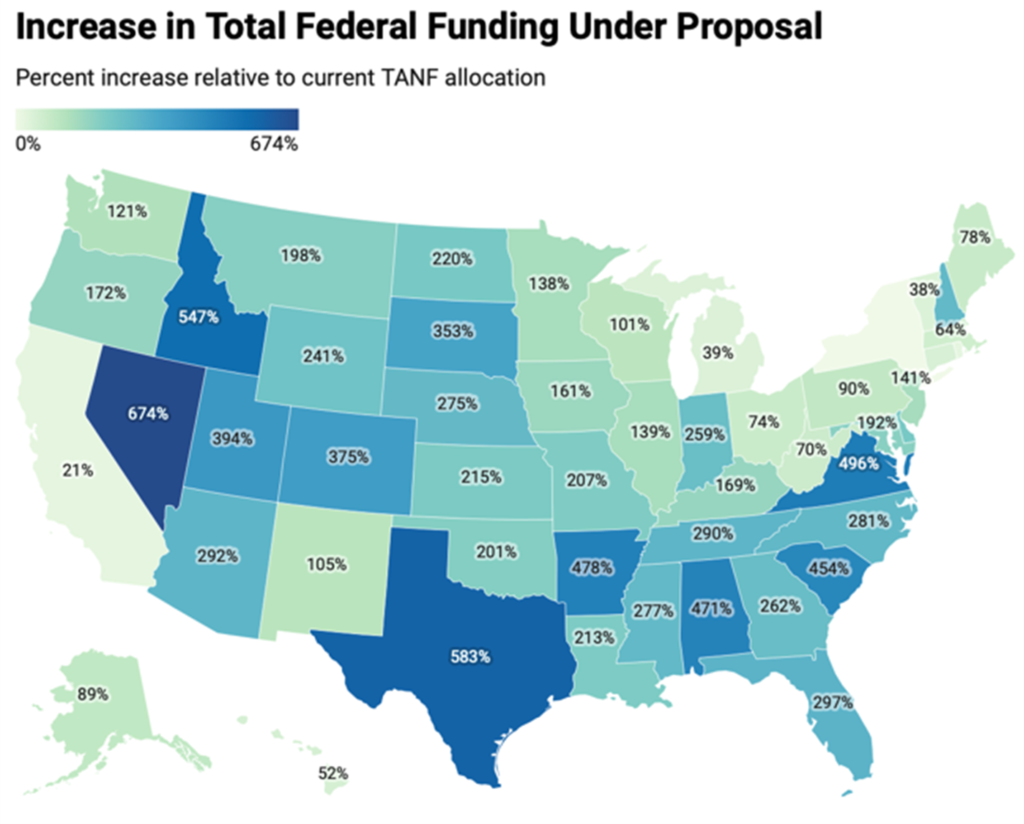

Under this scheme, 49 states would receive more in total funds for social assistance programs than they currently do from the TANF block grant. In almost every case, it would be significantly more (see Figure 4). New York and Washington DC would be slightly worse off. To ensure that they are held harmless, both would be allowed to keep their current aggregate amount, which would be left unadjusted for inflation or population change, until they find it more beneficial to switch to the new formula. This would slightly raise the cost of the reforms (from $35.9 billion to $36.2 billion) but still leave it slightly below the total value of the two programs it is replacing.

Indexing the SABG to inflation and population growth would result in total cost growing slowly over time relative to the SALT deduction and TANF block grant, both of which have been shrinking slowly over time due to the absence of indexation.

Funding from the SABG could be used toward family assistance, and general assistance as each state sees fit. Proper guardrails would be necessary to ensure that states do not use SABG funding as a slush fund for spending unrelated to social assistance.

Impact of Reforms

These reforms would have two important impacts on states. First, it would provide states with much needed fiscal relief. Social assistance is an essential function of state government. At the same time, states have limited fiscal capacity to provide it in many cases, and federal assistance has been shrinking or nonexistent for decades. Reforming and ramping up direct federal support enables states to better fulfill this responsibility. Additionally, we know that poverty is expensive for state governments. Giving them the resources that they need to tackle it can have positive externalities elsewhere in their budgets.

Second, it would bring American fiscal federalism in line with other countries by making it progressive on both a geographic and individual level without increasing the deficit. TANF is progressive on an individual level but regressive on a geographic level. The SALT deduction is regressive on both an individual and geographic level. Replacing both with flat per capita grants would make the system much more progressive for individuals and states alike.

The federal role in funding social assistance has been neglected for far too long. The economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic and our inability to quickly aid the most vulnerable members of our society has made this crystal clear. Luckily, policymakers need only look north for a worthwhile Canadian initiative to guide them as they design a better way to support states and their residents.

Joshua McCabe is an assistant professor of sociology and the assistant dean for social sciences at Endicott College. He is an expert on tax and social policy; author of The Fiscalization of Social Policy: How Taxpayers Trumped Children in the Fight Against Child Poverty (Oxford University Press); and a Niskanen Center Senior Fellow.