This article was originally published on Econofact on May 20, 2020.

The Issue:

The novel coronavirus outbreak has focused attention on the potential for disease transmission in prisons and jails. Prisons and jails present significant challenges to containing disease outbreak. Many called for immediate reductions in prison and jail populations in order to protect the health of inmates, correctional staff and visitors, and the communities in which detention facilities are located. Others expressed apprehension about the potential impacts of widespread inmate releases on public safety. The net effect on jail and prison populations — and spread of the virus within those facilities — has varied across places. Facilities are doing the best they can with limited information, but more guidance on optimal policy is crucial.

Those released from jails and prisons to limit the spread of COVID-19 may face difficult living conditions, scarce jobs and limited reentry services.

The Facts:

- The United States has the highest incarceration rate in the world, with an estimated incarcerated population of 2.3 million inmates. Slightly over half of the incarcerated population, or approximately 1.3 million people, is being held in state prisons. Another third of that population, or approximately 750,000 people, is being detained in county jails. The remainder are being held in federal detention facilities. The static measure of the county jail population understates the scope of county jail detention; county jails process approximately 11 million new admissions every year. Of those detained in county jails, approximately 75% are being held pretrial (that is, before a conviction).

- Jails and prisons present significant challenges to containing disease transmission. Maintaining social distance in correctional facilities is generally difficult, and incarcerated people often lack in-room access to hygiene products and water, factors that make it more difficult to contain the spread of the highly contagious novel coronavirus. Moreover, approximately 10% of the incarcerated population is 55 or older, and at higher risk for adverse outcomes. However, jails and prisons differ substantially in ways that may affect their ability to combat the spread of the virus. Jails tend to keep inmates in close quarters, and are not built for long stays; individuals often cycle from jails to communities and back over relatively short time horizons. Prisons are intended to house inmates for a year or more; social distancing may be easier in such spaces.

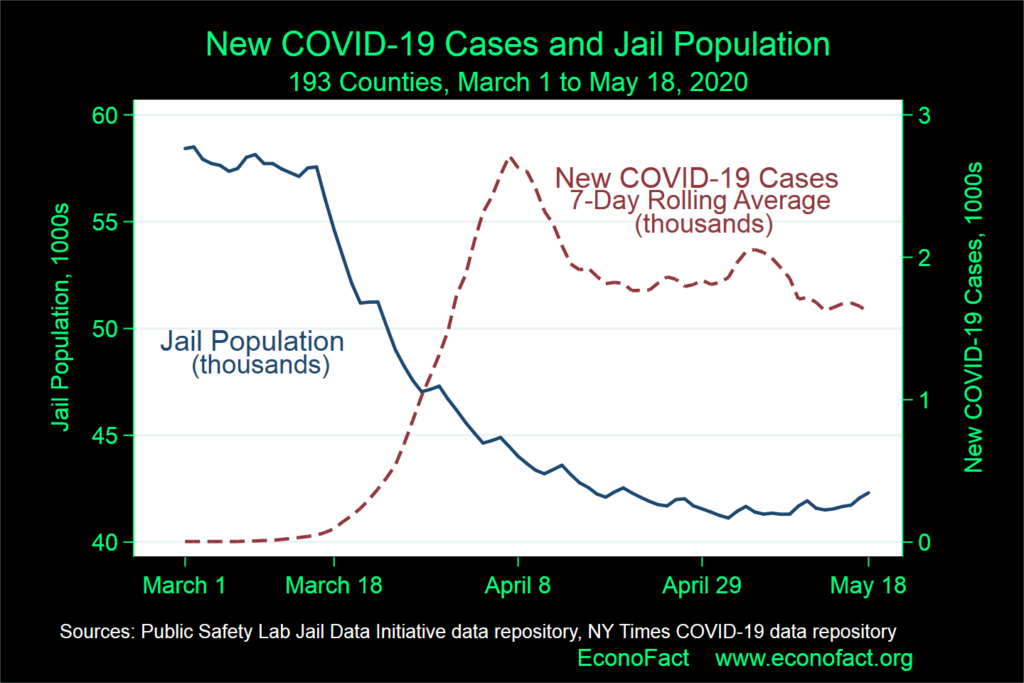

- Jail populations dropped dramatically in mid-March after the White House issued guidelines recommending social distancing. In a sample of 508 jails that post daily jail rosters online, representing a total population on March 16 of 130,508 detainees, the median jail population dropped by 30% between March 16 and May 17(the figure above reports the daily total jail population and a 7-day moving average of county-level COVID cases for the subset of 193 counties for which continuous daily data are available). Prison populations saw much smaller reductions; the typical prison reduced its population by only 5%. These changes appear to be exacerbating racial disparities in incarceration rates. Between March 16 and April 12, the white jail population in a sample of 341 jails reporting detainee data by race dropped by 25.5%, while the Hispanic jail population dropped by 20.3%, and the black jail population dropped by only 16.8%. It is not yet clear what is driving these disparate effects: underlying disparities in charges/characteristics that determine eligibility for release, differential treatment based on race when discretion is applied, or some combination of the two. The Public Safety Lab at New York University is currently conducting research on detainee-level data to determine the proportions of jail population reductions due to decreases in admissions and to increases in releases; the correlates of increased release probabilities; and the causal impacts of releases on public safety outcomes.