Executive Summary

The U.S. healthcare system faces a profound workforce crisis that threatens the availability and quality of care nationwide. A combination of factors—including demographic shifts, burnout, training bottlenecks, low wages for support roles, and uneven workforce distribution—has exacerbated shortages across the care spectrum. These issues are heightened by a rapidly aging population, an aging workforce, and systemic inefficiencies in the healthcare infrastructure. As a result, the U.S. is spending more on healthcare than any other country, yet reports worse health outcomes than most of its peer nations. These include high rates of chronic conditions, maternal and infant mortality, and preventable deaths.

Structural reforms are crucial for strengthening the domestic healthcare workforce, but these efforts will take years to yield results. In the meantime, immediate interventions are needed to address current shortages, with immigration presenting a compelling solution. Immigrants already play a critical role in the U.S. healthcare sector, accounting for 18% of the workforce, including a significant share of physicians, nurses, and home health aides. Despite this, restrictive U.S. immigration policies severely limit the entry and integration of foreign healthcare professionals, leaving critical gaps unaddressed.

This paper outlines targeted immigration reforms to alleviate workforce shortages across the healthcare system:

- DOCTORS Act: Reallocates unused Conrad 30 waivers to states that maximize their allotment, expanding opportunities for international medical graduates to serve in underserved areas.

- Credentialing “Sidelined” Workers: Reduces barriers for the 270,000 immigrants with healthcare qualifications working below their skill level by improving credential recognition and offering alternative licensure pathways.

- Replicating Conrad 30 for J-1 Trainees: Expands the J-1 visa trainee program to incentivize participation and address shortages in non-clinical yet essential healthcare roles.

- Au Pairs for Elder Care: Extends the J-1 au pair program to include elder care, easing the burden on families and increasing access to direct care for aging Americans.

- Schedule A Reform: Updates the Department of Labor’s Schedule A list to include additional healthcare occupations, streamlining visa applications for high-demand roles.

- Green Card Recapture: Recovers unused green cards from previous years and fixes the allocation formula, providing pathways to permanent residency for thousands of foreign-born healthcare workers.

Implementing these measures can provide immediate relief while laying the groundwork for a more sustainable healthcare workforce. Immigration reform, though often contentious, offers a bipartisan opportunity to address a critical national need, improving health outcomes and ensuring that every American has access to timely, high-quality care.

About the author

Cassandra Zimmer-Wong is an Immigration Policy Analyst at the Niskanen Center. Her research focuses on economic migration, increasing legal migration pathways, and refugee resettlement. Prior to joining Niskanen, Cassandra worked on the migration teams at the Center for Global Development and Labor Mobility Partnerships (LaMP). Previously, she was an American Voices Project Fellow at Stanford University and has interned for the Organization of American States, Inter-American Dialogue, and U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants. Cassandra holds a Bachelor of Arts in International Studies from American University and is pursuing a Master of Public Policy from Georgetown University.

Introduction

America’s healthcare system is at a critical juncture. For years, experts have warned of an impending workforce crisis, forecasting the onset of shortages within the next decade. However, that timeline has proven optimistic, with shortages already impacting occupations across the field.

While it is difficult to quantify exact shortage numbers, health outcomes in the U.S. reveal the need for increased practitioners at all levels across the spectrum of care. Compared to our peers in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the U.S. spends the most on healthcare as a share of the economy while simultaneously having the worst overall health outcomes.1 Among OECD countries, the U.S. ranks the lowest for life expectancy at birth, highest in death rates from avoidable or treatable conditions, and highest in maternal and infant mortality. The U.S. also leads in the prevalence of chronic conditions, rates of obesity, and suicide rates.2 Additionally, Americans visit physicians less frequently than their OECD counterparts and face some of the lowest ratios of physicians and hospital beds per 1,000 people.3 While numerous factors contribute to these alarming statistics, it is evident that timely, high-quality medical care is lacking. Workforce shortages across all levels of the healthcare system are a significant driver of these poor outcomes.

Meaningful structural changes are essential to build a robust domestic healthcare workforce. However, addressing the current workforce shortages requires immediate action. One practical and effective short-term solution is leveraging the potential of immigration.

Why are there shortages?

A labor shortage occurs when the demand for workers in a given occupation exceeds the available supply.4 However, quantifying and defining such shortages can be quite challenging in practice. The term “labor shortage” has become increasingly common in discussions about healthcare, yet accurately determining the precise number of doctors, nurses, or home health aides needed to close the gap—and predicting when they will be required—is far from an exact science. The following section details several potential factors contributing to the diminished domestic supply of healthcare workers across sectors.

Demographics

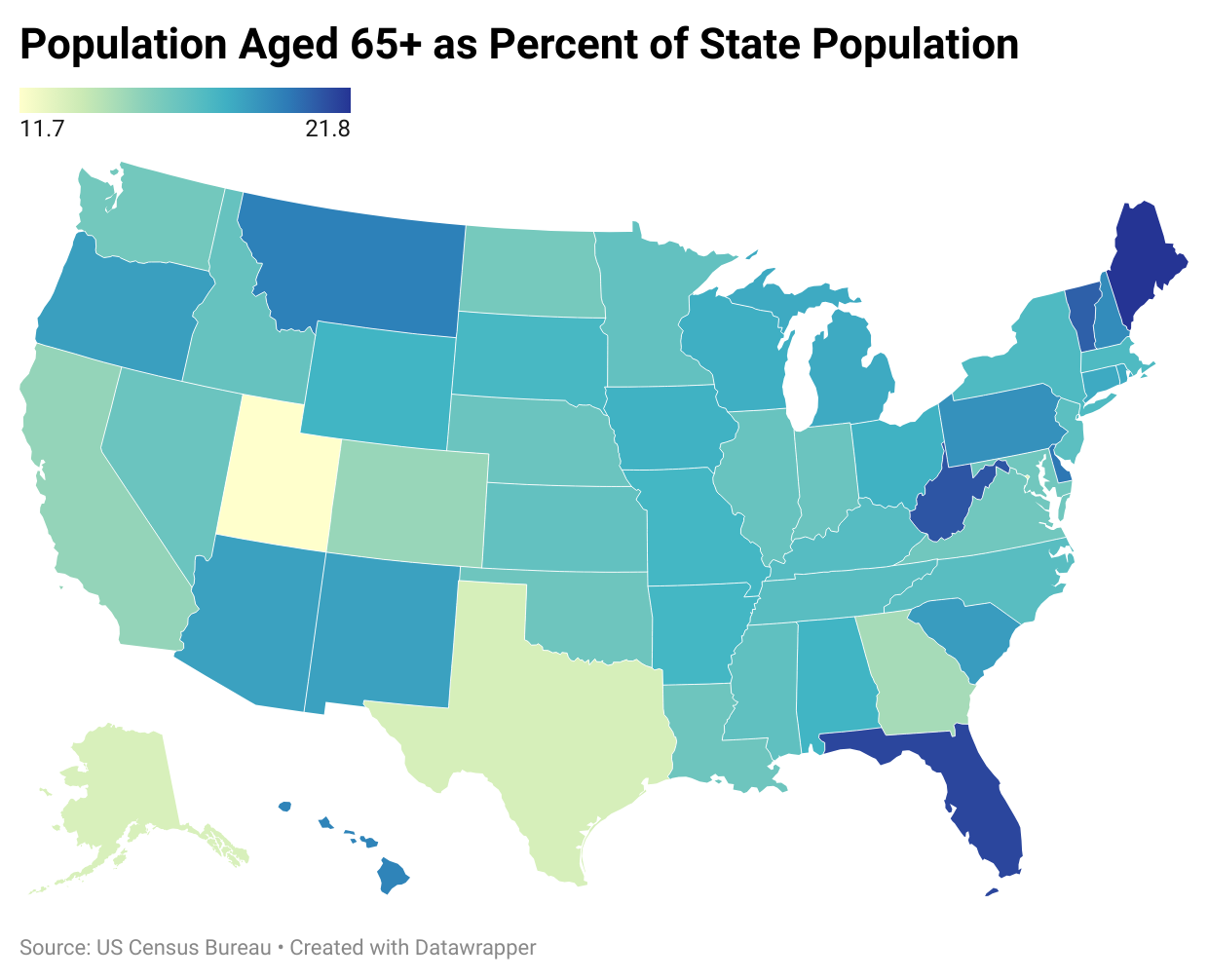

Workforce shortages in the healthcare industry are multifaceted, stemming from various contributing factors. One significant driver is the rapid aging of the U.S. population. By 2030, all members of the baby boomer generation will be over the age of 65,5 meaning that about 20% of the country will be of retirement age.6 By 2040, the population of Americans over 65 is projected to reach 80 million, and the population of adults aged 85 or older will quadruple from 2000 figures.7 Advanced age brings increased frailty8 and more complex medical needs.9 Furthermore, as Americans live longer, they are more likely to develop chronic conditions,10 requiring intensive and prolonged medical care.11 This demographic shift places growing demands on the healthcare system, necessitating a more robust workforce of healthcare practitioners and support staff.

It is also important to note that the healthcare workforce is aging alongside the general population. Currently, nearly half (45%) of active physicians are over 55, and 35% are expected to reach retirement age by 2030.12 This trend will significantly constrain the domestic supply of healthcare workers across various occupations, further exacerbating workforce shortages.

Professional burnout

Another significant issue facing the healthcare workforce is burnout, which drives many professionals to change jobs, retire early, or enter different careers entirely. While the COVID-19 pandemic intensified this problem, burnout had already reached crisis levels before 2020. At that time, up to 54% of nurses and physicians and 60% of medical students and residents reported experiencing symptoms of burnout.13

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare workers across the spectrum dealt with various challenges best summarized by the U.S. Surgeon General’s 2022 report Addressing Health Worker Burnout.14 The report notes that:

[A] rapidly changing healthcare environment, where advances in health information and biomedical technology are accompanied by burdensome administrative tasks, requirements, and a complex array of information to synthesize…[coupled with]…decades of underinvestment in public health, widening health disparities, lack of sufficient social investment…and a fragmented healthcare system have together created an imbalance between work demands and the resources of time and personnel.15

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the burnout crisis within the healthcare workforce, as professionals faced overwhelming patient loads, extended hours, supply shortages, inadequate personal protective equipment, stressful work environments, political polarization, and even harassment and violence.1617 Both clinical and non-clinical healthcare workers experienced burnout symptoms, stress, and mental health challenges.18 An October 2020 survey of healthcare workers in various roles–from housekeepers to physicians– revealed that 49% were experiencing burnout.19

By 2022, the CDC found that 46% of the healthcare workforce was experiencing burnout and considering seeking new employment.20 While it is challenging to fully quantify the total turnover in the healthcare sector following the COVID-19 pandemic, estimates suggest that about 18% of healthcare workers left their positions, with an additional 12% having been laid off.21 Among those who left, the numbers include around 100,000 registered nurses (RNs)22 and 117,000 physicians,23 highlighting the significant impact of the pandemic on the healthcare workforce.

Instructor shortage

A third factor contributing to the clinician workforce shortage is a need for more faculty to train the next generation of healthcare professionals.24 Across the country, insufficient numbers of instructors are forcing educational institutions to turn away qualified applicants, preventing them from entering healthcare careers. This issue is especially pronounced in nursing schools. According to a report from the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN), faculty shortages are the underlying reason that 91,938 qualified applicants to undergraduate and graduate nursing programs were rejected in 2021 alone.2526 In 2022, the AACN surveyed nursing programs nationwide and identified 2,166 full-time faculty vacancies, and an estimated need for an additional 128 positions to accommodate the growing demand for nursing students.27

There is a similar issue at medical schools, where the nationwide doctor shortage has exacerbated the shrinking number of instructors and supervisors of clinical hours for physicians in training.28 Additionally, medical schools have experienced a drastic decline in the number of faculty who receive tenured positions, further stifling efforts to recruit and retain full-time professors.29

Low pay for support workers

Healthcare workers in clinical settings, such as physicians and registered nurses, earn significantly higher wages than the average American worker. In 2023, the median salary for physicians was $236,000,30 while registered nurses earned a median salary of $86,070.31 However, these roles comprise less than 20% of the healthcare workforce, meaning most healthcare workers earn significantly less.

Most healthcare workers are employed in support roles, which are essential to the functioning of the healthcare system. Occupations like medical assistants and phlebotomists typically earn a median wage of just $13.48 an hour.32 Care workers, including home health aides and personal care workers, face even lower median pay, at $11.57 per hour. As a result, approximately 20% of these workers live in poverty, and more than 40% rely on public assistance.33

Maldistribution of workforce

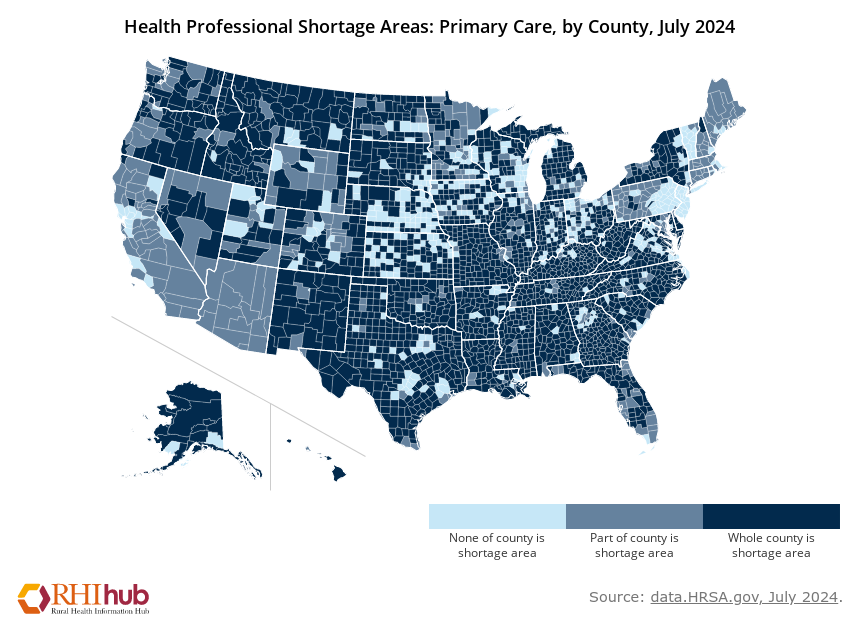

Approximately 20% of Americans — over 60 million people — live in rural areas,34 where significant health disparities exist compared to urban populations. Residents of rural areas experience poorer health outcomes, placing them at a higher risk for chronic illnesses and premature death.35

Individuals in rural areas tend to be older and have higher rates of illness than those in urban and suburban areas. They are more likely to smoke cigarettes and experience conditions like high blood pressure and obesity.36 Additionally, rural residents face elevated rates of heart disease, respiratory disease, cancer, stroke, unintentional injury and suicide, dental problems, maternal morbidity and mortality.37 These challenges are compounded by higher poverty rates, lower rates of health insurance coverage, and limited access to quality healthcare.38 A major barrier to healthcare access for rural Americans is the uneven distribution of healthcare workers –a problem worsened by the persistent workforce shortages across the industry.39

While workforce shortages vary among rural communities, they are widespread and persistent.40 In addition to the issues that the broader healthcare workforce faces–burnout, turnover, and demographic shifts–rural areas have also experienced significant hospital closures in recent years.41 The academic healthcare system’s urban-centric focus further exacerbates the problem, as access to training and education beyond the community college level is often limited in rural areas.42 As a result, fewer rural students enter the healthcare workforce.43 Those who do usually prefer urban areas for study, training, and residency; many do not return after completing their programs. Urban facilities and practices frequently offer higher salaries and better benefits, making it even more difficult to retain rural healthcare providers.44 Furthermore, providers trained in urban institutions may be unprepared for rural practice’s unique health concerns and systemic challenges. This mismatch can contribute to higher burnout and turnover rates, perpetuating the cycle of workforce shortages in rural communities.45

The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) designates certain geographic areas and populations as Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSA), Medically Underserved Areas (MUA), and Medically Underserved Populations (MUP).46 While rural areas account for more than 60% of primary care, mental health, and dental HPSAs,47 it is important to recognize that healthcare workforce maldistribution affects specific populations in rural and urban settings as well. These groups include homeless individuals, low-income communities, migrant farmworkers, and Tribal populations, all of whom face significant barriers to accessing adequate healthcare services.48

Shortage breakdown by sector

The following section examines healthcare workforce shortages across various occupational categories, organized by the educational attainment required to enter each role. This analysis utilizes the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) healthcare occupation classifications and groups occupations based on the level of education needed to qualify for each position. This approach was chosen because access to many U.S. employment-based visas effectively depends on educational qualifications.

Doctoral & professional degree professions

Healthcare occupations that require a doctoral or professional degree include audiologists, chiropractors, dentists, optometrists, pharmacists, physical therapists, physicians, podiatrists, and surgeons. BLS predicts that each profession in this category is projected to have a positive job growth rate, except podiatrists.49 Additionally, there are shortages in each of these occupations aside from podiatrists and chiropractors.

Physicians are the most frequently discussed occupation in the doctoral and professional degree category when addressing healthcare workforce shortages–and for good reason. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) projects a shortage of 86,000 physicians by 2036, encompassing primary care (the most significant gap), specialists, and surgeons.50 This includes shortages across primary care (the most significant shortage), specialists, and surgeons.51 This shortage is driven by demographic shifts, including an aging population that requires more intensive and specialized care. Compounding the issue is the aging physician workforce, with many nearing retirement, further diminishing the available supply of doctors.52

Another significant factor contributing to the physician shortage is the residency bottleneck.53 Since the 1980s, efforts to control the supply of physicians in the U.S. have resulted in a cap on Medicare funding for residency slots.54 This limitation has led to thousands of medical school graduates going unmatched each year, creating an artificially constrained and insufficient domestic supply of physicians. Importantly, current shortage estimates only reflect the existing allocation of doctors in the country. The AAMC report revealed that if underserved communities received care at the same rates as well-served communities, the U.S. would have already needed an additional 202,800 physicians.55 This figure is three to six times higher than current shortage estimates, underscoring the severity of the problem.56

Master’s degree professions

Healthcare occupations requiring a master’s degree include athletic trainers, genetic counselors, nurse anesthetists, nurse midwives, nurse practitioners (APRN), occupational therapists, orthotists and prosthetists, physician assistants, and speech-language pathologists. There are shortages across all occupations in this category, and each has a projected job growth rate in the double digits, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).57

The shortage in maternity care providers is particularly acute. The U.S. has the highest maternal death rate out of any high-income nation (22 per 100,000 live births) and staggeringly high rates (50 per 100,000 live births) for Black women.58 About 80% of these deaths are preventable,59 but only when proper care is provided throughout pregnancy, birth, and the postpartum period. Midwives, a Master’s degree occupation, are vital to addressing this gap. Globally, midwives are “often considered the backbone of the reproductive health system,” yet in the U.S., they face both significant underutilization and a shortage of at least 8,200 workers. A particularly critical barrier to care in the U.S. is the absence of obstetric clinicians in many areas—one in three counties does not have a single obstetric provider.60

To meet demand, the U.S. will need at least 29,200 Advanced Practice Registered Nurses (APRNs), including nurse practitioners, nurse anesthetists, and nurse midwives, annually through 2032.61 Midwives are particularly crucial in mitigating OB/GYN shortages nationwide, as they can attend most low-risk births. Their care consistently correlates with improved quality, greater patient attention, and better maternal and infant mortality outcomes.62

Bachelor’s degree professions

Healthcare occupations requiring a bachelor’s degree include clinical laboratory technologists and technicians, dietitians and nutritionists, exercise physiologists, medical dosimetrists, recreational therapists, and registered nurses. While there are shortages across most of these roles, recreational therapists and exercise physiologists are exceptions. Despite these disparities, according to the BLS, all occupations in this category have positive projected job growth rates.63

Registered nurses (RNs) are among the most frequently discussed occupations regarding healthcare shortages in the U.S. The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) predicts a shortage of 78,610 full-time RNs by 2025 and 63,720 by 2030.64 Compounding this issue, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce projects 193,100 RN job openings annually between 2022 and 2032, while only 177,400 nurses are expected to enter the workforce over the entire decade—falling short of the demand for even a year of openings.65

RN shortages have far-reaching effects, including reduced care access, diminished quality, rising healthcare costs,66 and increased rates of hospital closures, particularly in rural areas.67 These shortages are driven by several factors, including demographic shifts, high turnover rates, mass retirements, low enrollment in nursing programs, and limited legal immigration pathways for foreign-born nurses to enter the U.S.68 69

Associate’s degree professions

Healthcare occupations requiring an associate’s degree include dental hygienists, diagnostic medical sonographers and cardiovascular technologists and technicians, health information technologists and medical registrars, nuclear medicine technologists, physical therapy assistants and aides, radiation therapists, radiologic and MRI technologists, respiratory therapists, occupational therapy assistants and aides. All of these occupations, except nuclear medicine technologists, physical therapy assistants, and aides, are experiencing shortages and have positive projected job growth rates according to the BLS.70

Postsecondary non-degree professions

Healthcare occupations requiring a postsecondary non-degree certificate include EMTs, paramedics, licensed practical and licensed vocational nurses, massage therapists, medical assistants, medical records specialists, medical transcriptionists, occupational health and safety specialists and technicians, phlebotomists, psychiatric technicians and aides, surgical assistants and technologists, dental assistants, and nursing assistants and orderlies. Shortages exist across most of these occupations, except for licensed practical and licensed vocational nurses and medical transcriptionists. Additionally, all occupations in this category are projected to see positive job growth, except for medical transcriptionists, according to the BLS.71

Emergency Medical Technicians (EMT) and paramedics are vital in providing critical emergency medical care, often serving as the first responders to life-threatening events, accidents, and natural disasters. However, the U.S. urgently needs 40,000 full-time EMTs and paramedics by 2030,72 with severe shortages already crippling the field.

In 2022, turnover rates were alarmingly high–36% for EMTs and 27% for paramedics73–largely due to low wages, burnout, and poor work-life balance.74 A survey revealed that more than one-third of new hires left the profession within their first year.75 Some states have even removed age requirements for the profession to fill gaps, allowing individuals as young as 15 to serve as EMTs.76 These staffing gaps have serious consequences, including longer response times and overworked personnel, ultimately putting lives at greater risk.77

High school diploma professions

Healthcare occupations that require a high school diploma include home health and personal care aides, opticians, and pharmacy technicians. Despite the current shortages in the home health, personal care aide, and pharmacy technician fields, the BLS projects positive job growth for all three categories.78

The prognosis for the future availability of direct care workers–like home health and personal care aides–is especially critical. As of 2023, approximately 5 million direct care workers provide essential services in private residences, residential care facilities, and nursing homes nationwide.79 These workers are vital to supporting elderly adults and those with disabilities, enabling them to receive care in their homes and communities.80 By 2031, an additional 1 million jobs are projected to be added to the direct sector–more than in any other occupation in the country.81

However, quantifying this shortage is difficult due to the lack of a national data collection system for the field. Current estimates suggest a shortage of 151,000 direct care workers by 2030, increasing to 355,000 by 2040.82 These shortages have severe consequences for patients. A 2023 survey of nursing homes revealed that 54% had to limit admissions due to staffing shortages, resulting in an average of 25% of referred patients being unable to secure a bed.83

Immigration as a solution

Immigrants play a crucial role in the U.S. healthcare workforce, with nearly 2.8 million foreign-born workers employed in the sector as of 2021–accounting for 18% of the total industry.84 Their contributions became particularly evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, as immigrants represented a significant proportion of essential and frontline workers.85 They are also disproportionately represented in several key healthcare occupations, including physicians and surgeons (26% of the workforce), registered nurses (16%), and home health aides (40%).86 87Immigrants in the healthcare sector hold a range of legal statuses, from naturalized citizens to undocumented workers, reflecting the diverse backgrounds that sustain the industry’s labor force.88

U.S. immigration policy imposes significant barriers for immigrant health professionals seeking work in the country.89 There are currently no visa pathways designed specifically for healthcare workers, forcing them to compete with professionals from all other sectors for the limited number of employer-sponsored visas available.

Additionally, the immigration system imposes annual caps on key visa categories, such as the H-1B, EB-1, EB-2, and EB-3, which are commonly used by university degree-holding professionals to work in the U.S. as physicians, surgeons, and registered nurses. These caps limit the number of available visas to 65,000 for H-1B and 120,000 for EB-1 through EB-3 combined.90 Moreover, no specific legal visa pathways are tailored for healthcare workers in professions that typically require an associate’s degree, postsecondary non-degree certifications, or a high school diploma.

The current system is flawed, expensive, and too slow to adequately address the demand for foreign-born healthcare workers in the U.S.91 While comprehensive immigration reform remains a distant prospect, there are immediate opportunities to amend or adjust the existing system to enable more migrant workers to help address critical healthcare shortages.

DOCTORS Act

The Conrad 30 Waiver Program allows international medical graduates (IMGs) on J-1 visas to waive the 2-year foreign residence requirement by committing to practice medicine for three years in designated a Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA), Medically Underserved Area (MUA) or with a Medically Underserved Population (MUP) for three years.92 Each state can sponsor up to 30 IMGs annually under this program. The Directing Our Country’s Transfer of Residency Slots (DOCTORS) Act93 was introduced in Congress in January 2024 with the express aim of addressing the shortage of physicians by reallocating unused waivers from the Conrad 30 program to states that use their maximum 30 waivers.94

Some states, such as New York, California, West Virginia, and Texas, typically utilize all 30 of their Conrad 30 waivers each year. Others, including Utah, Delaware, Alaska, and Nevada, consistently leave unused waivers.95 Under the proposed DOCTORS Act, state agencies must report the number of unused waivers by the end of each fiscal year. These unused waivers would then be redistributed equally among states that had fully utilized their maximum allocation of 30 waivers, with the total number of redistributed waivers divisible by three.96

Credentialing “sidelined” workers

According to researchers from the Migration Policy Institute (MPI), approximately 270,000 immigrants in the U.S. with medical or health undergraduate degrees are working below their skill level or entirely out of the healthcare workforce.97 This phenomenon, often called “brain waste,” is primarily attributed to the significant barriers these workers encounter when trying to have their foreign academic and professional credentials recognized in the U.S.98

Individual state governments govern the licensing of medical professionals, each with unique requirements and examinations.99 Migrant workers seeking licensure face challenges such as translating and verifying their foreign credentials, undergoing costly re-testing processes, meeting stringent English-language proficiency requirements, and, for physicians, repeating medical residency programs. These obstacles deter qualified professionals from re-entering the healthcare workforce and exacerbate existing workforce shortages in the U.S.

States can take several steps to reduce barriers to obtaining professional and occupational licenses for immigrant healthcare workers. One approach is to offer licenses regardless of immigration status.100 Only immigrants with specific visa statuses and a Social Security number can receive medical licensing.

However, some states–such as California,101 Colorado,102 Illinois,103 Nevada,104 and New Mexico105–have enacted laws allowing individuals to apply for professional licenses using an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN) and have removed immigration-related requirements.106 Additionally, states like Arkansas,107 Nebraska,108 and New York109 have offered professional licensure to all individuals with federal employment authorization, including those with Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and Temporary Protected Status (TPS).110

Additionally, states can develop programs to up-skill individuals and increase English language proficiency.111 Colorado112 has a clinical readiness program that helps international medical graduates develop skills to prepare for residency programs. Maine113 and Washington114 have programs that provide work-based learning courses for migrants that help with the English language and up-skilling in specific professions.115

Finally, four states—Tennessee, Illinois, Florida, and Virginia—–have enacted laws that allow international medical graduates (IMGs) to bypass residency requirements, allowing them alternative pathways to physician licensure.116 Additionally, eleven states have introduced or passed legislation to streamline the licensure process for IMGs: Vermont, Massachusetts, Wisconsin, Iowa, Missouri, Alabama, Colorado, Arizona, Nevada, Idaho, and Washington.117

Replicate Conrad 30 for J-1 Trainees

While the J-1 visa is available to foreign medical graduates, it is not limited to physicians: it also includes a track for trainees. This track allows foreign nationals with at least a postsecondary certificate to gain up to 18 months of practical occupational experience and training within the U.S. workforce.118

Despite its potential, the J-1 trainee program is underutilized–only 10,645 trainees participated across 91 employers in 24 states in 2023.119 If the State Department were to replicate the Conrad 30 program for J-1 trainees, enabling states to sponsor a specific number of trainees annually, it could incentivize greater participation. Such a program could help address workforce shortages in critical occupations across the U.S..120

Currently, J-1 trainees are prohibited from working in roles that involve direct patient contact or care, including childcare and elder care. However, “health-related occupations” are among the eligible categories in the J-1 trainee program. This includes roles such as medical transcriptionists, occupational health and safety specialists and technicians, medical records specialists, and pharmacy technicians, amongst others, who would be eligible for the trainee program. While these occupations are not direct care roles, they are essential to the functioning of the healthcare system.

Au Pairs for elder care

According to an AARP survey, 77% of American adults would prefer to age at home,121 and data shows that the percentage of adults living in nursing homes has steadily declined over the past two decades.122 This trend highlights the growing preference for “aging in place,” a choice often made possible by access to professional home health care. Still, the direct care worker shortage is the most pronounced in the healthcare industry.

One potential solution is for the Department of State to expand the Au Pair Program123 to include elder care. By adapting the program to support the growing demand for home-based care, this expansion could help address the critical need for direct care workers, allowing more older adults to remain in their homes.

The Au Pair Program enables American families to host foreign au pairs for up to two years in a work-study arrangement.124 Participants arrive in the U.S. with childcare training, English language proficiency, and a comprehensive background and personality check. While working as live-in caregivers for infants and children, they can also earn credits at U.S. colleges or universities. The program operates without taxpayer funding, as private agencies charge administrative fees and host families pay wages. It is also highly popular—more than 21,000 families participated in 2023 alone. Currently, there is no cap on J-1 visas for au pairs. However, expanding the program to include elder care would require amending Title 22 CFR Section 62.31—Au Pairs. Experts suggest that bipartisan support for such a proposal is likely,125 as it would provide significant benefits to middle-class families and seniors. By offering an affordable solution to the growing demand for elder care, this expansion could address critical workforce shortages while aligning with the program’s existing framework.

Schedule A reform

Schedule A is a list of specific occupations for which the Department of Labor has declared insufficient number of workers in the U.S. and determined that the employment of immigrants would not adversely affect the wages and working conditions of domestic employees.126 Employers aiming to hire for a Schedule A designated position can largely bypass the requirement to demonstrate there was an exhaustive search for an American worker – saving employers six months or more.127 The Schedule A list was first created in 1965 and gave the Secretary of Labor discretion to amend the list “at any time, upon his own initiative.”128 While it was updated through the following decades, the last substantial update to the list was in 1991–and the only occupations on the list were nurses, physical therapists, and immigrants “of exceptional ability.”129

The Schedule A list should be updated to reflect today’s labor needs and to bolster the healthcare workforce. Doing so would most likely.130 Experts suggest that physicians, surgeons,131 and home health aides132 would be prioritized in an updated Schedule A list.

Green card recapture

In 1990, Congress established a cap on the number of green cards that can be issued annually in certain family-based and all employment-based categories.133 annually in certain family-based and all employment-based categories.134 Congress intended for all allotted green cards to be issued each year and created a mechanism for unused green cards to “roll over” from the employment-based category to the family-based category the following year.135 However, the process is fundamentally flawed due to the formula used to calculate the rollover numbers.136 Specifically, in years when a high number of family-based green cards are issued, no employment-based green cards effectively roll over, leading to their permanent loss.137

As a result, the green cards that Congress intended foreign-born workers effectively disappear, leaving immigrants in a “line” that can stretch over 50 years.138 What’s more, most of these would-be employment-based green card recipients are already living in the U.S., waiting to adjust to a different status–for example, a physician with an H-1B temporary visa.139 These individuals face significant challenges: they have limited ability to travel internationally, switch jobs or change employers, and they remain vulnerable to shifts in immigration policy.140 Moreover, their spouses struggle to obtain legal work authorization, and their children risk “aging out,” losing eligibility to secure permanent residency as dependents.141

Congress has the ability to address the issue by both fixing the flawed formula to prevent the loss of green cards and “recapturing” unused green cards from previous years. Notably, Congress has recaptured a limited number of green cards in the past.142 Taking these steps would provide a pathway to citizenship for 220,000143 immigrants, including many current and future healthcare workers who are essential to the nation’s well-being.

Conclusion

The United States is grappling with a severe healthcare workforce crisis, marked by critical shortages across various sectors and worsening health outcomes nationwide. An aging population, rising burnout among healthcare workers, and an underdeveloped training infrastructure have combined to create a perfect storm, placing unprecedented strain on the system. Despite outspending every other nation on healthcare, the U.S. continues to lag behind its peers in key health metrics, underscoring the urgent need for innovative solutions.

Immigration presents a practical and effective strategy for addressing these shortages.By reforming immigration policies to streamline the entry of qualified healthcare workers and removing barriers that prevent skilled immigrants from fully contributing in the workforce, the U.S. can begin to bridge the growing gaps in care and strengthen the healthcare system.

References

AARP. “Where We Live, Where We Age: Trends in Home and Community Preferences.” AARP, 2021. https://livablecommunities.aarpinternational.org/.

America Counts Staff. “2020 Census Will Help Policymakers Prepare for the Incoming Wave of Aging Boomers.” United States Census Bureau, February 25, 2022. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2019/12/by-2030-all-baby-boomers-will-be-age-65-or-older.html.

American Association of College of Nursing. “2021-2022 Enrollment and Graduations in Baccalaureate and Graduate Programs in Nursing.” American Association of College of Nursing. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://www.aacnnursing.org/store/product-info/productcd/idsr_22enrollbacc.

American Medical Association. “AMA Advocacy Insights Webinar Series: What’s Exacerbating the Physician Shortage Crisis-and What’s Needed to Fix It.” American Medical Association, May 22, 2024. https://www.ama-assn.org/member-benefits/events/ama-advocacy-insights-webinar-series-what-s-exacerbating-physician-shortage#:~:text=The%20physician%20workforce%2C%20like%20our,U.S.%20aged%2055%20or%20older.

American Nurses Association. “Nurses in the Workforce.” American Nurses Association, October 14, 2017. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/workforce/.

Balch, Bridget. “Tenure Is Declining in U.S. Medical Schools. Could This Threaten Academic Freedom?” Association of American Medical Colleges, April 23, 2024. https://www.aamc.org/news/tenure-declining-us-medical-schools-could-threaten-academic-freedom.

Batalova, Jeanne. “Immigrant Health-Care Workers in the United States.” Migration Policy Institute, April 7, 2023. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/immigrant-health-care-workers-united-states-2021.

Bier, David J. Cato.org, June 18, 2019. https://www.cato.org/publications/policy-analysis/immigration-wait-times-quotas-have-doubled-green-card-backlogs-are-long.

BridgeU.S.A. “Au Pair Program.” U.S. Department of State. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://j1visa.state.gov/programs/au-pair.

BridgeU.S.A. “Explore Data by Top Sending Country 2023.” U.S. Department of State. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://j1visa.state.gov/basics/facts-and-figures/top-sending-countries-2023/.

BridgeU.S.A. “Trainee Program.” U.S. Department of State. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://j1visa.state.gov/programs/trainee.

Cabral, A.R. “Why It’s Still Hard to Get into Medical School despite a Doctor Shortage.” U.S. News and World Report, May 6, 2024. https://www.usnews.com/education/best-graduate-schools/top-medical-schools/articles/why-its-still-hard-to-get-into-medical-school-despite-a-doctor-shortage.

California Legislative Information. “SB-1159: Bill Text.” California Legislative Information. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201320140SB1159.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. “Older Adults.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/cdi/indicator-definitions/older-adults.html.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “About Rural Health.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/rural-health/php/about/index.html#:~:text=People%20who%20live%20in%20rural%20areas%20in%20the%20United%20States,likely%20to%20have%20health%20insurance.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Health Workers Face A Mental Health Crisis.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, October 24, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/health-worker-mental-health/index.html#:~:text=The%20nation’s%20health%20workers%20need%20support&text=The%20COVID%2D19%20pandemic%20presented,higher%20than%20before%20the%20pandemic.

Colorado General Assembly. “International Medical Graduate Integrate Health-Care Workforce.” Colorado General Assembly, May 10, 2022. https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/hb22-1050.

Congress.gov. “Text – S.2719 – 118th Congress (2023-2024): DOCTORS Act.” September 5, 2023. https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/2719/text.

Cornell Law School. “22 CFR § 62.31 – Au Pairs.” Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/22/62.31#:~:text=As%20a%20condition%20of%20participation,amount%20not%20to%20exceed%20%24500.

Esterline, Cecilia. “The Case for Updating Schedule A – Niskanen Center.” Niskanen Center , December 2, 2022. https://www.niskanencenter.org/the-case-for-updating-schedule-a/#endnote4.

Fiore, Kristina. “More States Cut Training Requirements for Some International Medical Graduates.” Medical News, March 14, 2024. https://www.medpagetoday.com/special-reports/exclusives/109168.

FWD.us. “Green Card Recapture and Reform Would Reduce Immigration Backlogs.” FWD.us, September 14, 2022. https://www.fwd.us/news/green-card-recapture/.

Galvin, Gaby. “Nearly 1 in 5 Health Care Workers Have Quit Their Jobs during the Pandemic.” Morning Consult Pro, June 29, 2023. https://pro.morningconsult.com/articles/health-care-workers-series-part-2-workforce.

Gelatt, Julia. “Explainer: How the U.S. Legal Immigration System Works.” Migration Policy Institute, July 2, 2019. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/content/explainer-how-us-legal-immigration-system-works.

Gunja, Munira Z., Evan D. Gumas, and Reginald D. Williams. “U.S. Health Care from a Global Perspective, 2022: Accelerating Spending, Worsening Outcomes.” The Commonwealth Fund, January 31, 2023. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2023/jan/us-health-care-global-perspective-2022.

Gunja, Munira Z., Evan D. Gumas, Relebohile Masitha, and Laurie C. Zephyrin. “Insights into the U.S. Maternal Mortality Crisis: An International Comparison.” The Commonwealth Fund, June 4, 2024. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2024/jun/insights-us-maternal-mortality-crisis-international-comparison.

Gutierrez, Sonia, and Julio Sandoval. “Rocky Mountain PBS.” Colorado’s undocumented residents can now get career licenses on August 2, 2021. https://www.rmpbs.org/blogs/rocky-mountain-pbs/new-law-allows-undocumented-immigrants-to-get-career-licenses.

Harootunian, Lisa, Kamryn Perry, Allison Buffett, Marilyn Werber Serafini, and Brian O’Gara. “Addressing the Direct Care Workforce Shortage.” Bipartisan Policy Center, December 7, 2023. https://bipartisanpolicy.org/report/addressing-the-direct-care-workforce-shortage/.

Harrah, Scott. “Medically Underserved Areas in the U.S..” University of Medicine and Health Sciences, November 5, 2020. https://www.umhs-sk.org/blog/medically-underserved-areas-regions-where-u-s-needs-doctors.

Health Resources and Services Administration. “Allied Health Workforce Projections, 2016-2030: Emergency Medical Technicians and Paramedics.” Health Resources and Services Administration. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bureau-health-workforce/data-research/emergency-medical-technicians-paramedics-2016-2030.pdf.

Health Resources and Services Administration. “Nurse Workforce Projections, 2020-2035.” Health Resources and Services Administration, November 2022. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bureau-health-workforce/Nursing-Workforce-Projections-Factsheet.pdf.

Health Resources and Services Administration. “Strengthening the Rural Health Workforce to Improve Health Outcomes in Rural Communities.” Health Resources and Services Administration, April 2022. https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hrsa/advisory-committees/graduate-medical-edu/reports/cogme-april-2022-report.pdf.

Health Resources and Services Administration. “What Is Shortage Designation?” Health Resources and Services Administration. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/workforce-shortage-areas/shortage-designation.

Hoover, Makinizi, Isabella Lucy, and Katie Mahoney. “Data Deep Dive: A National Nursing Crisis.” U.S. Chamber of Commerce, May 22, 2024. https://www.uschamber.com/workforce/nursing-workforce-data-center-a-national-nursing-crisis.

HRSA Bureau of Health Workforce. “Designated Health Professional Shortage Areas Statistics.” Health Resources and Services Administration, September 30, 2024. https://data.hrsa.gov/Default/GenerateHPSAQuarterlyReport.

Illinois General Assembly. “ Bill Status of SB3109.” Illinois General Assembly. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://www.ilga.gov/legislation/billstatus.asp?DocNum=3109&GAID=14&GA=100&DocTypeID=SB&LegID=110694&SessionID=91.

Kinder, Molly. The Brookings Institution, May 28, 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/essential-but-undervalued-millions-of-health-care-workers-arent-getting-the-pay-or-respect-they-deserve-in-the-covid-19-pandemic/.

Kumar, Claire, Helen Dempster, Megan O’Donnell, and Cassandra Zimmer. “ Migration and the Future of Care Supporting Older People and Care Workers.” ODI, March 2022. https://media.odi.org/documents/INFOGRAPHICS_migration_and_the_future_of_care.pdf.

Lyons, Barbara, and Molly O’Malley Watts. “Addressing the Shortage of Direct Care Workers: Insights from Seven States.” The Commonwealth Fund, March 19, 2024. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2024/mar/addressing-shortage-direct-care-workers-insights-seven-states.

Maine Legislature. “An Act To Facilitate Entry of Immigrants into the Workforce.” Maine Legislature. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://legislature.maine.gov/legis/bills/bills_129th/billtexts/HP120901.asp.

Martin, Brendan, Nicole Kaminski-Ozturk, Charlie O’Hara, and Richard Smiley. “Examining the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Burnout and Stress among U.S. Nurses.” NCSBN, 2023. https://www.ncsbn.org/research-item/examining_impact_of_covid_on_stress.

Medical University of South Carolina. “Frailty: A New Predictor of Outcome as We Age.” Medical University of South Carolina. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://muschealth.org/medical-services/geriatrics-and-aging/healthy-aging/frailty#:~:text=Frailty%20Prevalence,in%20those%2085%20and%20older.

Mendoza, Adriana, and Iris Hinh. “Removing Professional Barriers for People Who Are Immigrants Can Help States and Families Prosper.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 24, 2023. https://www.cbpp.org/blog/removing-professional-barriers-for-people-who-are-immigrants-can-help-states-and-families.

Mensik, Hailey. “Over 200,000 Healthcare Workers Quit Jobs Last Year.” Healthcare Dive, October 26, 2022.https://www.healthcaredive.com/news/covid-pandemic-healthcare-burnout-providers-quit-jobs/634946/.

Mercer, Marsha. “States Strive to Reverse Shortage of Paramedics, Emts • Stateline.” Stateline, June 6, 2023. https://stateline.org/2023/02/06/states-strive-to-reverse-shortage-of-paramedics-emts/.

Migration Policy Institute. “As Health-Care Sector Seeks to Fill Pressing Labor Needs, New MPI Brief Examines Untapped Immigrant Talent Pool.” Migration Policy Institute, May 26, 2022. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/news/health-care-untapped-immigrant-talent.

Mitchell, Molly. “New Arkansas Laws Remove Barriers for Immigrants, despite Legislature’s Rightward Turn.” Arkansas Times, June 30, 2021. https://arktimes.com/news/2021/06/30/new-arkansas-laws-remove-barriers-for-immigrants-despite-legislatures-rightward-turn.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. “Front Matter.” National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2019. Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25521.

National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians. “States Strive to Reverse Shortage of Paramedics, EMTs.” National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians, February 7, 2023. https://www.naemt.org/WhatsNewALLNEWS/2023/02/07/states-strive-to-reverse-shortage-of-paramedics-emts.

Nebraska Legislature. “Legislative Bill 947.” Nebraska Legislature, April 20, 2016. https://nebraskalegislature.gov/FloorDocs/104/PDF/Slip/LB947.pdf.

Nevada State Legislature. “AB275.” NELIS. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://www.leg.state.nv.us/App/NELIS/REL/80th2019/Bill/6498/Text.

New York State Education Department. “Board of Regents Permanently Adopts Regulations to Allow DACA Recipients to Apply for Teacher Certification and Professional Licenses.” New York State Education Department, May 17, 2016. https://www.nysed.gov/news/2016/board-regents-permanently-adopts-regulations-allow-daca-recipients-apply-teacher.

Orr, Robert. “Unmatched: Repairing the U.S. Medical Residency Pipeline.” The Niskanen Center, September 2021. https://www.niskanencenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Unmatched-Repairing-the-U.S.-Residency-Pipeline.pdf.

PHI. “Phi’s Workforce Data Center.” PHI, October 11, 2024. https://www.phinational.org/policy-research/workforce-data-center/#tab=National+Data .

PHI. “Understanding the Direct Care Workforce.” PHI, September 2, 2024. https://www.phinational.org/policy-research/key-facts-faq/.

Prasad, Kriti, Colleen McLoughlin, Martin Stillman, Sara Poplau, Elizabeth Goelz, Sam Taylor, Nancy Nankivil, et al. “Characterizing Long Covid in an International Cohort: 7 Months of Symptoms and Their Impact.” EClinicalMedicine, May 16, 2021. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34308300/.

Preston, Rob. “The Shortage of U.S. Healthcare Workers in 2023.” Oracle, January 2023. https://www.oracle.com/human-capital-management/healthcare-workforce-shortage/.

Ramón, Cristobal, and Rachel Iacono. “Policy Recommendation: Lowering Barriers for Foreign Health Care Workers Can Help U.S. Fight Coronavirus.” Bipartisan Policy Center, April 9, 2020. https://bipartisanpolicy.org/blog/policy-recommendation-lowering-barriers-for-foreign-health-care-workers-can-help-u-s-fight-coronavirus/.

Rural Health Information Hub. “Rural Healthcare Workforce.” Rural Health Information Hub. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/health-care-workforce.

Shakya, Shishir. “Understanding the Role of Immigrants in the U.S. Health Sector: Employment Trends from 2007–21.” Baker Institute, January 3, 2024. https://www.bakerinstitute.org/research/understanding-role-immigrants-us-health-sector-employment-trends-2007-21.

Spoehr, Christina. “New AAMC Report Shows Continuing Projected Physician Shortage.” Association of American Medical Colleges, March 21, 2024. https://www.aamc.org/news/press-releases/new-aamc-report-shows-continuing-projected-physician-shortage#:~:text=Media%20Contacts&text=According%20to%20new%20projections%20published,to%2086%2C000%20physicians%20by%202036.

StaffDash. “Closing the Gap: How EMT, EMS, and Paramedic Scholarships Are Filling the Staffing Shortage.” Staffdash.com. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://staffdash.com/closing-the-gap-how-emt-ems-and-paramedic-scholarships-are-filling-the-staffing-shortage/.

Stoneburner A, Lucas R, Fontenot J, Brigance C, Jones E, DeMaria AL. Nowhere to Go: Maternity Care Deserts Across the U.S.. (Report No 4). March of Dimes. 2024. https://www.marchofdimes.org/sites/default/files/2024-09/2024_MoD_MCD_Report.pdf

The John A. Hartford Foundation. “Complex Care Needs of Older Adults.” The John A. Hartford Foundation. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://www.johnahartford.org/ar2009/Complex_Care_Needs_of_Older_Adults.html.

Tikkanen, Roosa, and Melinda K. Abrams. 2020. “U.S. Health Care from a Global Perspective, 2019: Higher Spending, Worse Outcomes?” The Commonwealth Fund, January 30, 2020. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/jan/us-health-care-global-perspective-2019.

Torres-Valverde, Diana. “Expanding License Opportunities for Immigrants Helps N.M.” Santa Fe New Mexican, March 21, 2022. https://www.santafenewmexican.com/opinion/my_view/expanding-license-opportunities-for-immigrants-helps-n-m/article_5833085e-6cbe-11eb-a8c8-23909c8e351f.html.

Trost SL, Beauregard J, Njie F, et al. Pregnancy-Related Deaths: Data from Maternal Mortality Review Committees in 36 U.S. States, 2017-2019. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/maternal-mortality/php/data-research/mmrc-2017-2019.html

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics: Physicians.” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, April 3, 2024. https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes291229.htm.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics: Registered Nurses.” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, April 3, 2024. https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes291141.htm.

U.S. Census Bureau. “2023 National Population Projections Tables: Main Series.” United States Census Bureau, October 31, 2023. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2023/demo/popproj/2023-summary-tables.html?utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=newsletter_axiosfutureofhealthcare&stream=top#_ga=2.123123211.1416043120.1715523350-1195561148.1690218011&_gac=1.60375519.1714922975.CjwKCAjw3NyxBhBmEiwAyofDYagg6AEysGJlXm9HDhxgbY-EJMhrpGOlMO5y0KOXaLhpiejrM5goqxoC1PwQAvD_BwE.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. “Chapter 7 – Schedule a Designation Petitions.” U.S.CIS, April 10, 2024. https://www.uscis.gov/policy-manual/volume-6-part-e-chapter-7.

U.S. Department of Labor. “Final Rule, Labor Certification Process for the Permanent …” U.S. Department of Labor, December 2, 1965. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/OALJ/PUBLIC/INA/REFERENCES/FEDERAL_REGISTER/30_FED._REG._14979_(DEC._3,_1965).PDF.

U.S. Department of State. “Directory of Visa Categories.” U.S. Department of State. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/us-visas/visa-information-resources/all-visa-categories.html.

U.S. Surgeon General. “Addressing Health Worker Burnout: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on Building a Thriving Health Workforce.” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2022. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/health-worker-wellbeing-advisory.pdf.

U.S.DA Economic Research Service. “What Is Rural?” U.S.DA Economic Research Service, March 26, 2024. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/rural-classifications/what-is-rural/.

Urban Institute. “The U.S. Population Is Aging.” Urban Institute, April 4, 2022. https://www.urban.org/policy-centers/cross-center-initiatives/program-retirement-policy/projects/data-warehouse/what-future-holds/us-population-aging.

Veneri, Carolyn M. “Can Occupational Labor Shortages Be Identified Using Available Data?” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, March 1999. https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/1999/03/art2full.pdf.

Washington Legislature. “ENGROSSED SUBSTITUTE SENATE BILL 5693.” Washington Legislature, March 10, 2022. https://lawfilesext.leg.wa.gov/biennium/2021-22/Pdf/Bills/Senate%20Passed%20Legislature/5693-S.PL.pdf?q=20220518115539.

World Health Organization. “Investing in Midwife-Led Interventions Could Save 4.3 Million Lives per Year, New Study Finds.” World Health Organization, December 3, 2020. https://www.who.int/news/item/03-12-2020-investing-in-midwife-led-interventions-could-save-4.3-million-lives-per-year-new-study-finds.

Zimmer, Cassandra. “We Should Replicate Conrad 30 for J-1 Trainees – Niskanen Center.” Niskanen Center, August 21, 2024. https://www.niskanencenter.org/we-should-replicate-conrad-30-for-j-1-trainees/.

Footnotes

- Tikkanen, Roosa, and Melinda K. Abrams. 2020. “U.S. Health Care from a Global Perspective, 2019: Higher Spending, Worse Outcomes?” The Commonwealth Fund, January 30, 2020. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/jan/us-health-care-global-perspective-2019. ↩︎

- Gunja, Munira Z., Evan D. Gumas, and Reginald D. Williams. “U.S. Health Care from a Global Perspective, 2022: Accelerating Spending, Worsening Outcomes.” The Commonwealth Fund, January 31, 2023. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2023/jan/us-health-care-global-perspective-2022. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Veneri, Carolyn M. “Can Occupational Labor Shortages Be Identified Using Available Data?” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, March 1999. https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/1999/03/art2full.pdf. ↩︎

- America Counts Staff. “2020 Census Will Help Policymakers Prepare for the Incoming Wave of Aging Boomers.” United States Census Bureau, February 25, 2022. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2019/12/by-2030-all-baby-boomers-will-be-age-65-or-older.html. ↩︎

- U.S. Census Bureau. “2023 National Population Projections Tables: Main Series.” United States Census Bureau, October 31, 2023. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2023/demo/popproj/2023-summary-tables.html?utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=newsletter_axiosfutureofhealthcare&stream=top#_ga=2.123123211.1416043120.1715523350-1195561148.1690218011&_gac=1.60375519.1714922975.CjwKCAjw3NyxBhBmEiwAyofDYagg6AEysGJlXm9HDhxgbY-EJMhrpGOlMO5y0KOXaLhpiejrM5goqxoC1PwQAvD_BwE. ↩︎

- Urban Institute. “The U.S. Population Is Aging.” Urban Institute, April 4, 2022. https://www.urban.org/policy-centers/cross-center-initiatives/program-retirement-policy/projects/data-warehouse/what-future-holds/us-population-aging. ↩︎

- Medical University of South Carolina. “Frailty: A New Predictor of Outcome as We Age.” Medical University of South Carolina. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://muschealth.org/medical-services/geriatrics-and-aging/healthy-aging/frailty#:~:text=Frailty%20Prevalence,in%20those%2085%20and%20older. ↩︎

- The John A. Hartford Foundation. “Complex Care Needs of Older Adults.” The John A. Hartford Foundation . Accessed October 18, 2024. https://www.johnahartford.org/ar2009/Complex_Care_Needs_of_Older_Adults.html. ↩︎

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. “Older Adults.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/cdi/indicator-definitions/older-adults.html. ↩︎

- “How Much Care Will You Need?” LongTermCare.gov. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://acl.gov/ltc/basic-needs/how-much-care-will-you-need. ↩︎

- American Medical Association. “AMA Advocacy Insights Webinar Series: What’s Exacerbating the Physician Shortage Crisis-and What’s Needed to Fix It.” American Medical Association, May 22, 2024. https://www.ama-assn.org/member-benefits/events/ama-advocacy-insights-webinar-series-what-s-exacerbating-physician-shortage#:~:text=The%20physician%20workforce%2C%20like%20our,U.S.%20aged%2055%20or%20older. ↩︎

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. “Front Matter.” National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2019. Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25521. ↩︎

- U.S. Surgeon General. “Addressing Health Worker Burnout: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on Building a Thriving Health Workforce.” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2022. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/health-worker-wellbeing-advisory.pdf. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . “Health Workers Face A Mental Health Crisis.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, October 24, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/health-worker-mental-health/index.html#:~:text=The%20nation’s%20health%20workers%20need%20support&text=The%20COVID%2D19%20pandemic%20presented,higher%20than%20before%20the%20pandemic. ↩︎

- U.S. Surgeon General. 2022. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Prasad, Kriti, Colleen McLoughlin, Martin Stillman, Sara Poplau, Elizabeth Goelz, Sam Taylor, Nancy Nankivil, et al. “Characterizing Long Covid in an International Cohort: 7 Months of Symptoms and Their Impact.” EClinicalMedicine, May 16, 2021. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34308300/. ↩︎

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2023. ↩︎

- Galvin, Gaby. “Nearly 1 in 5 Health Care Workers Have Quit Their Jobs during the Pandemic.” Morning Consult Pro, June 29, 2023. https://pro.morningconsult.com/articles/health-care-workers-series-part-2-workforce. ↩︎

- Martin, Brendan, Nicole Kaminski-Ozturk, Charlie O’Hara, and Richard Smiley. “Examining the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Burnout and Stress among U.S. Nurses.” NCSBN, 2023. https://www.ncsbn.org/research-item/examining_impact_of_covid_on_stress. ↩︎

- Mensik, Hailey. “Over 200,000 Healthcare Workers Quit Jobs Last Year.” Healthcare Dive, October 26, 2022.https://www.healthcaredive.com/news/covid-pandemic-healthcare-burnout-providers-quit-jobs/634946/. ↩︎

- Preston, Rob. “The Shortage of U.S. Healthcare Workers in 2023.” Oracle, January 2023. https://www.oracle.com/human-capital-management/healthcare-workforce-shortage/. ↩︎

- American Association of College of Nursing . “2021-2022 Enrollment and Graduations in Baccalaureate and Graduate Programs in Nursing.” American Association of College of Nursing . Accessed October 18, 2024. https://www.aacnnursing.org/store/product-info/productcd/idsr_22enrollbacc. ↩︎

- Preston, Rob. 2023. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Cabral, A.R. “Why It’s Still Hard to Get into Medical School despite a Doctor Shortage.” U.S. News and World Report, May 6, 2024. https://www.usnews.com/education/best-graduate-schools/top-medical-schools/articles/why-its-still-hard-to-get-into-medical-school-despite-a-doctor-shortage. ↩︎

- Balch, Bridget. “Tenure Is Declining in U.S. Medical Schools. Could This Threaten Academic Freedom?” Association of American Medical Colleges, April 23, 2024. https://www.aamc.org/news/tenure-declining-us-medical-schools-could-threaten-academic-freedom. ↩︎

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics: Physicians.” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, April 3, 2024. https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes291229.htm. ↩︎

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics: Registered Nurses.” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, April 3, 2024. https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes291141.htm. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- U.S.DA Economic Research Service. “What Is Rural?” U.S.DA Economic Research Service, March 26, 2024. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/rural-classifications/what-is-rural/. ↩︎

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “About Rural Health.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/rural-health/php/about/index.html#:~:text=People%20who%20live%20in%20rural%20areas%20in%20the%20United%20States,likely%20to%20have%20health%20insurance. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Health Resources and Services Administration. “Strengthening the Rural Health Workforce to Improve Health Outcomes in Rural Communities.” Health Resources and Services Administration, April 2022. https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hrsa/advisory-committees/graduate-medical-edu/reports/cogme-april-2022-report.pdf. ↩︎

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2024. ↩︎

- Rural Health Information Hub. “Rural Healthcare Workforce.” Rural Health Information Hub. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/health-care-workforce. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Health Resources and Services Administration. 2022. ↩︎

- Rural Health Information Hub. ↩︎

- Harrah, Scott. “Medically Underserved Areas in the U.S..” University of Medicine and Health Sciences, November 5, 2020. https://www.umhs-sk.org/blog/medically-underserved-areas-regions-where-u-s-needs-doctors. ↩︎

- Rural Health Information Hub. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Health Resources and Services Administration. “What Is Shortage Designation?” Health Resources and Services Administration. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/workforce-shortage-areas/shortage-designation. ↩︎

- HRSA Bureau of Health Workforce. “Designated Health Professional Shortage Areas Statistics.” Health Resources and Services Administration, September 30, 2024. https://data.hrsa.gov/Default/GenerateHPSAQuarterlyReport. ↩︎

- Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs) and Medically Underserved Areas/Populations (MUA/P) Shortage Designation Types, August 1, 2019. https://www.hhs.gov/guidance/document/hpsa-and-muap-shortage-designation-types. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Spoehr, Christina. “New AAMC Report Shows Continuing Projected Physician Shortage.” Association of American Medical Colleges, March 21, 2024. https://www.aamc.org/news/press-releases/new-aamc-report-shows-continuing-projected-physician-shortage#:~:text=Media%20Contacts&text=According%20to%20new%20projections%20published,to%2086%2C000%20physicians%20by%202036. ↩︎

- Dall, Tim, Ryan Reynolds, Ritashree Chakrabarti, Clark Ruttinger, Patrick Zarek, and Owen Parker. “The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections From 2021 to 2036.” Association of American Medical Colleges, March 2024. https://www.aamc.org/media/75236/download?attachment. ↩︎

- Spoehr, Christina. 2024. ↩︎

- Orr, Robert. “Unmatched: Repairing the U.S. Medical Residency Pipeline.” The Niskanen Center, September 2021. https://www.niskanencenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Unmatched-Repairing-the-U.S.-Residency-Pipeline.pdf. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Spoehr, Christina. 2024. ↩︎

- Dall, Tim et.al. 2024. ↩︎

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Occupational Outlook Handbook.” 2024. ↩︎

- Gunja, Munira Z., Evan D. Gumas, Relebohile Masitha, and Laurie C. Zephyrin. “Insights into the U.S. Maternal Mortality Crisis: An International Comparison.” The Commonwealth Fund, June 4, 2024. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2024/jun/insights-us-maternal-mortality-crisis-international-comparison. ↩︎

- Trost SL, Beauregard J, Njie F, et al. Pregnancy-Related Deaths: Data FFarom Maternal Mortality Review Committees in 36 U.S. States, 2017-2019. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/maternal-mortality/php/data-research/mmrc-2017-2019.html ↩︎

- Stoneburner A, Lucas R, Fontenot J, Brigance C, Jones E, DeMaria AL. Nowhere to Go: Maternity Care Deserts Across the U.S.. (Report No 4). March of Dimes. 2024. https://www.marchofdimes.org/sites/default/files/2024-09/2024_MoD_MCD_Report.pdf ↩︎

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. “Nursing Shortage Fact Sheet.” American Association of Colleges of Nursing, May 2024. https://www.aacnnursing.org/news-data/fact-sheets/nursing-shortage. ↩︎

- World Health Organization. “Investing in Midwife-Led Interventions Could Save 4.3 Million Lives per Year, New Study Finds.” World Health Organization, December 3, 2020. https://www.who.int/news/item/03-12-2020-investing-in-midwife-led-interventions-could-save-4.3-million-lives-per-year-new-study-finds. ↩︎

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Occupational Outlook Handbook.” 2024. ↩︎

- Health Resources and Services Administration. “Nurse Workforce Projections, 2020-2035.” Health Resources and Services Administration, November 2022. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bureau-health-workforce/Nursing-Workforce-Projections-Factsheet.pdf. ↩︎

- Hoover, Makinizi, Isabella Lucy, and Katie Mahoney. “Data Deep Dive: A National Nursing Crisis.” U.S. Chamber of Commerce, May 22, 2024. https://www.uschamber.com/workforce/nursing-workforce-data-center-a-national-nursing-crisis. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- American Nurses Association. “Nurses in the Workforce.” American Nurses Association, October 14, 2017. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/workforce/. ↩︎

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Occupational Outlook Handbook.” 2024. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Health Resources and Services Administration. “Allied Health Workforce Projections, 2016-2030: Emergency Medical Technicians and Paramedics.” Health Resources and Services Administration. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bureau-health-workforce/data-research/emergency-medical-technicians-paramedics-2016-2030.pdf. ↩︎

- National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians. “States Strive to Reverse Shortage of Paramedics, EMTs.” National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians, February 7, 2023. https://www.naemt.org/WhatsNewALLNEWS/2023/02/07/states-strive-to-reverse-shortage-of-paramedics-emts. ↩︎

- Mercer, Marsha. “States Strive to Reverse Shortage of Paramedics, Emts • Stateline.” Stateline, June 6, 2023. https://stateline.org/2023/02/06/states-strive-to-reverse-shortage-of-paramedics-emts/. ↩︎

- National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians. 2023. ↩︎

- https://stateline.org/2023/02/06/states-strive-to-reverse-shortage-of-paramedics-emts/ ↩︎

- StaffDash. “Closing the Gap: How EMT, EMS, and Paramedic Scholarships Are Filling the Staffing Shortage.” Staffdash.com. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://staffdash.com/closing-the-gap-how-emt-ems-and-paramedic-scholarships-are-filling-the-staffing-shortage/. ↩︎

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Occupational Outlook Handbook.” 2024. ↩︎

- PHI. “Phi’s Workforce Data Center.” PHI, October 11, 2024. https://www.phinational.org/policy-research/workforce-data-center/#tab=National+Data. ↩︎

- Lyons, Barbara, and Molly O’Malley Watts. “Addressing the Shortage of Direct Care Workers: Insights from Seven States.” The Commonwealth Fund, March 19, 2024. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2024/mar/addressing-shortage-direct-care-workers-insights-seven-states. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- PHI. “Understanding the Direct Care Workforce.” PHI, September 2, 2024. https://www.phinational.org/policy-research/key-facts-faq/. ↩︎

- Harootunian, Lisa, Kamryn Perry, Allison Buffett, Marilyn Werber Serafini, and Brian O’Gara. “Addressing the Direct Care Workforce Shortage.” Bipartisan Policy Center, December 7, 2023. https://bipartisanpolicy.org/report/addressing-the-direct-care-workforce-shortage/. ↩︎

- Batalova, Jeanne. “Immigrant Health-Care Workers in the United States.” Migration Policy Institute, April 7, 2023. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/immigrant-health-care-workers-united-states-2021. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Shakya, Shishir. “Understanding the Role of Immigrants in the U.S. Health Sector: Employment Trends from 2007–21.” Baker Institute, January 3, 2024. https://www.bakerinstitute.org/research/understanding-role-immigrants-us-health-sector-employment-trends-2007-21. ↩︎

- Batalova, Jeanne. 2023. ↩︎

- Shakya, Shishir. 2024. ↩︎

- U.S. Department of State. “Directory of Visa Categories.” U.S. Department of State. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/us-visas/visa-information-resources/all-visa-categories.html. ↩︎

- Shakya, Shishir. 2024. ↩︎

- U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. “Conrad 30 Waiver Program.” U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, May 15, 2020. https://www.uscis.gov/working-in-the-united-states/students-and-exchange-visitors/conrad-30-waiver-program. ↩︎

- Congress.gov. “Text – S.2719 – 118th Congress (2023-2024): DOCTORS Act.” September 5, 2023. https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/2719/text. ↩︎

- Office of Elise Stefanik. “Stefanik Helps Introduce Bill to Address Doctor Shortage.” Congresswoman Elise Stefanik, January 11, 2024. https://stefanik.house.gov/2024/1/stefanik-helps-introduce-bill-to-address-doctor-shortage. ↩︎

- Carl Shusterman Immigration Lawyer. “Conrad 30 Usage, J Waivers for Physicians, Imgs.” Shusterman Law, September 4, 2022. https://www.shusterman.com/conrad-30-usage/. ↩︎

- Office of Elise Stefanik. 2024. ↩︎

- Migration Policy Institute. “As Health-Care Sector Seeks to Fill Pressing Labor Needs, New MPI Brief Examines Untapped Immigrant Talent Pool.” Migration Policy Institute, May 26, 2022. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/news/health-care-untapped-immigrant-talent. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ramón, Cristobal, and Rachel Iacono. “Policy Recommendation: Lowering Barriers for Foreign Health Care Workers Can Help U.S. Fight Coronavirus.” Bipartisan Policy Center, April 9, 2020. https://bipartisanpolicy.org/blog/policy-recommendation-lowering-barriers-for-foreign-health-care-workers-can-help-u-s-fight-coronavirus/. ↩︎

- Mendoza, Adriana, and Iris Hinh. “Removing Professional Barriers for People Who Are Immigrants Can Help States and Families Prosper.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 24, 2023. https://www.cbpp.org/blog/removing-professional-barriers-for-people-who-are-immigrants-can-help-states-and-families. ↩︎

- California Legislative Information. “SB-1159: Bill Text.” California Legislative Information. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201320140SB1159. ↩︎

- Gutierrez, Sonia, and Julio Sandoval. “Rocky Mountain PBS.” Colorado’s undocumented residents can now get career licenses, August 2, 2021. https://www.rmpbs.org/blogs/rocky-mountain-pbs/new-law-allows-undocumented-immigrants-to-get-career-licenses. ↩︎

- Illinois General Assembly. “ Bill Status of SB3109.” Illinois General Assembly. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://www.ilga.gov/legislation/billstatus.asp?DocNum=3109&GAID=14&GA=100&DocTypeID=SB&LegID=110694&SessionID=91. ↩︎

- Nevada State Legislature. “AB275.” NELIS. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://www.leg.state.nv.us/App/NELIS/REL/80th2019/Bill/6498/Text. ↩︎

- Torres-Valverde, Diana. “Expanding License Opportunities for Immigrants Helps N.M.” Santa Fe New Mexican, March 21, 2022. https://www.santafenewmexican.com/opinion/my_view/expanding-license-opportunities-for-immigrants-helps-n-m/article_5833085e-6cbe-11eb-a8c8-23909c8e351f.html. ↩︎

- Mendoza, Adriana, and Iris Hinh. 2023. ↩︎

- Mitchell, Molly. “New Arkansas Laws Remove Barriers for Immigrants, despite Legislature’s Rightward Turn.” Arkansas Times, June 30, 2021. https://arktimes.com/news/2021/06/30/new-arkansas-laws-remove-barriers-for-immigrants-despite-legislatures-rightward-turn. ↩︎

- Nebraska Legislature. “Legislative Bill 947.” Nebraska Legislature, April 20, 2016. https://nebraskalegislature.gov/FloorDocs/104/PDF/Slip/LB947.pdf. ↩︎

- New York State Education Department. “Board of Regents Permanently Adopts Regulations to Allow DACA Recipients to Apply for Teacher Certification and Professional Licenses.” New York State Education Department, May 17, 2016. https://www.nysed.gov/news/2016/board-regents-permanently-adopts-regulations-allow-daca-recipients-apply-teacher. ↩︎

- Mendoza, Adriana, and Iris Hinh. 2023. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Colorado General Assembly. “International Medical Graduate Integrate Health-Care Workforce.” Colorado General Assembly, May 10, 2022. https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/hb22-1050. ↩︎

- Maine Legislature. “An Act To Facilitate Entry of Immigrants into the Workforce.” Maine Legislature. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://legislature.maine.gov/legis/bills/bills_129th/billtexts/HP120901.asp. ↩︎

- Washington Legislature. “ENGROSSED SUBSTITUTE SENATE BILL 5693.” Washington Legislature, March 10, 2022. https://lawfilesext.leg.wa.gov/biennium/2021-22/Pdf/Bills/Senate%20Passed%20Legislature/5693-S.PL.pdf?q=20220518115539. ↩︎

- Mendoza, Adriana, and Iris Hinh. 2023. ↩︎

- Fiore, Kristina. “More States Cut Training Requirements for Some International Medical Graduates.” Medical News, March 14, 2024. https://www.medpagetoday.com/special-reports/exclusives/109168. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- BridgeU.S.A. “Trainee Program.” U.S. Department of State. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://j1visa.state.gov/programs/trainee. ↩︎

- Zimmer, Cassandra. “We Should Replicate Conrad 30 for J-1 Trainees – Niskanen Center.” Niskanen Center, August 21, 2024. https://www.niskanencenter.org/we-should-replicate-conrad-30-for-j-1-trainees/. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- AARP. “Where We Live, Where We Age: Trends in Home and Community Preferences.” AARP, 2021. https://livablecommunities.aarpinternational.org/. ↩︎

- Hipp, Deb. “Aging in Place Statistics and Facts in 2024.” Forbes, July 24, 2024. https://www.forbes.com/health/healthy-aging/aging-in-place-statistics/. ↩︎

- BridgeU.S.A. “Au Pair Program.” U.S. Department of State. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://j1visa.state.gov/programs/au-pair. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Crebo-Rediker, Heidi.2023. ↩︎

- U.S. Department of Labor. “Final Rule, Labor Certification Process for the Permanent …” U.S. Department of Labor, December 2, 1965. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/OALJ/PUBLIC/INA/REFERENCES/FEDERAL_REGISTER/30_FED._REG._14979_(DEC._3,_1965).PDF. ↩︎

- Esterline, Cecilia. “The Case for Updating Schedule A – Niskanen Center.” Niskanen Center , December 2, 2022. https://www.niskanencenter.org/the-case-for-updating-schedule-a/#endnote4. ↩︎

- U.S. Department of Labor. 1965. ↩︎

- U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. “Chapter 7 – Schedule a Designation Petitions.” U.S.CIS, April 10, 2024. https://www.uscis.gov/policy-manual/volume-6-part-e-chapter-7. ↩︎

- Esterline, Cecilia. 2022. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Kumar, Claire, Helen Dempster, Megan O’Donnell, and Cassandra Zimmer. “ Migration and the Future of Care Supporting Older People and Care Workers.” ODI, March 2022. https://media.odi.org/documents/INFOGRAPHICS_migration_and_the_future_of_care.pdf. ↩︎

- Gelatt, Julia. “Explainer: How the U.S. Legal Immigration System Works.” Migration Policy Institute, July 2, 2019. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/content/explainer-how-us-legal-immigration-system-works. ↩︎

- FWD.us. “Green Card Recapture and Reform Would Reduce Immigration Backlogs.” FWD.us, September 14, 2022. https://www.fwd.us/news/green-card-recapture/. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎