The Inflation Reduction Act showers largesse on American clean energy, from solar power to heat pumps to carbon-cutting industrial practices. But when it comes to electric vehicles (EVs), the new law effectively pulls back on federal support. The number of vehicles subsidized is likely to crater from around 200,000 last year to fewer than 15,000 next year. Even so, sales are predicted to keep rising. If those predictions come to pass, it will suggest that the limited EV tax credits we have offered until now don’t drive overall demand, and retrenching them was a good move. But could EV subsidies nonetheless encourage demand amongst a particularly important segment of drivers?

IRA slashes the types of vehicles eligible for the federal subsidy

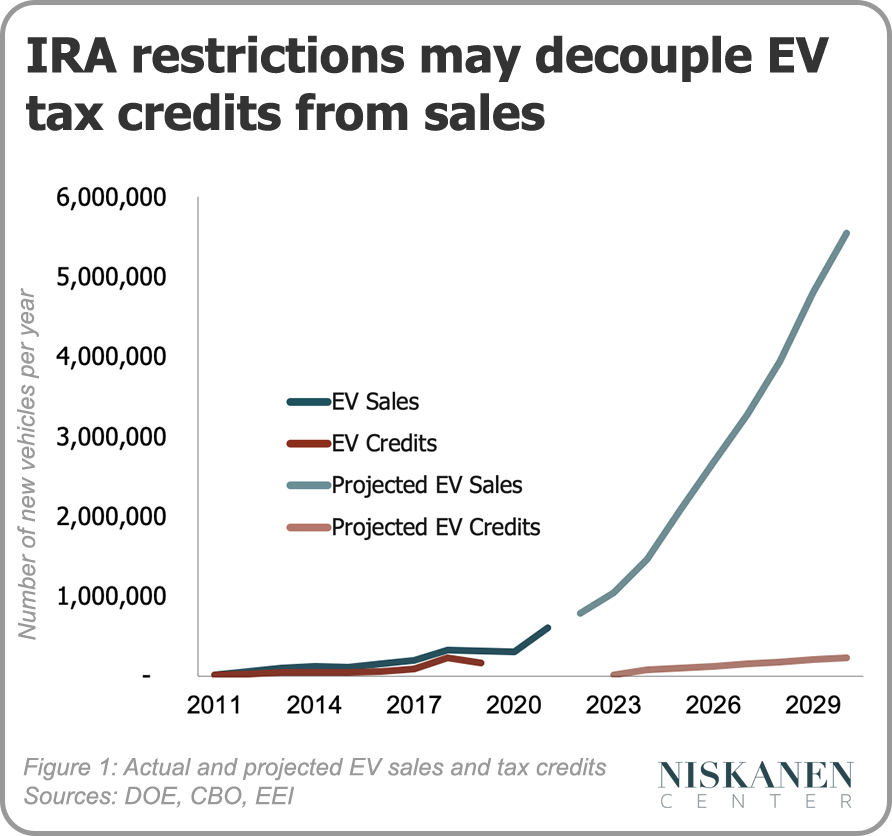

Until now, the number of EVs sold has tracked the number of EVs receiving a federal tax credit – sales (teal line in the graph below) and credits (red line in the graph below) roughly rose and fell together. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) predicts that after the IRA, the number of vehicles receiving tax credits will plummet, with the government disbursing fewer than 15,000 credits in 2023. Meanwhile, the Edison Electric Institute predicts that EV sales in the U.S. will continue to soar, reaching a million next year and more than 5 million in 2030. If both things happen, the emerging gap between EVs sold (lighter teal line in the graph below) and EVs receiving a federal tax credit (lighter red line in the graph below) will grow astonishingly wide. (EV credit data is not available for 2020-2022).

The reason CBO estimates so few vehicles will be eligible is that the IRA placed strict new manufacturing and supply chain requirements on vehicles to access the credit. Going forward, the full $7,500 EV tax credit will only be available for vehicles that have been 1) assembled in North America with 2) batteries partially and eventually completely assembled in North America using 3) increasing portions of critical minerals from the U.S. or its trading partners. In the longer term, this will incentivize car manufacturers to invest in domestic plants and to diversify away from China’s dominance of battery and critical-mineral supplies. But in the shorter term it will shrink the pool of vehicles eligible for the tax credit from more than a hundred to closer to a dozen.

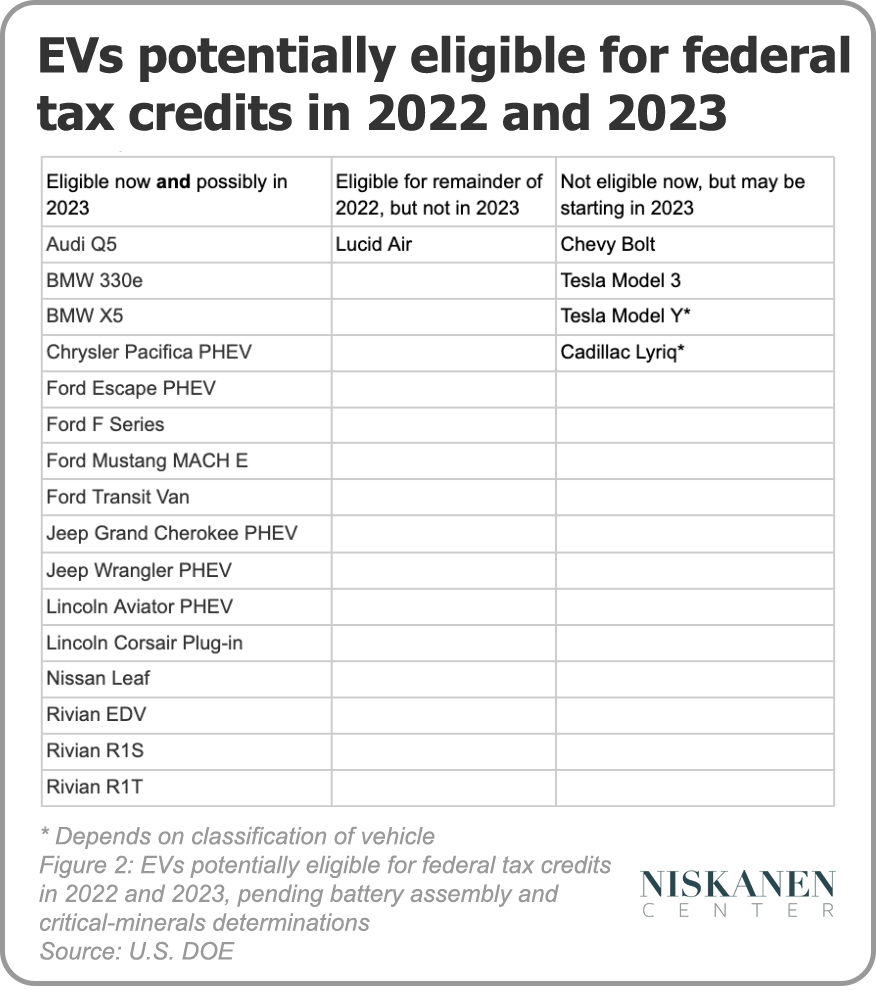

Prior to the IRA, 131 vehicles from 35 different manufacturers were eligible for between $2,500 to $7,500. For the remainder of 2022, only 17 models that are assembled in the U.S. but whose manufacturers have not yet sold 200,000 vehicles will be eligible. Starting in January 2023, Tesla, Chevy, and GMC vehicles will become eligible as the manufacturer cap is lifted, bringing four assembled-in-North America models back into eligibility for a total of 21 vehicles from 12 manufacturers. But the limitations on battery assembly and critical mineral supplies will start in January. The Energy Department and IRS have not yet evaluated which of the models listed below also have battery assembly and critical-minerals supply chains that meet the IRA’s criteria, so it could be that even fewer models are eligible come January.

Who benefits from EV tax credits?

EV buyers tend to be wealthy, so legislators tried to block higher-income Americans from benefiting from the subsidies. Only single filers with incomes below $150,000 and joint filers with incomes below $300,000 will be eligible when purchasing a new EV. The IRA also excludes the most expensive vehicles – SUVs costing more than $80,000 and sedans more than $55,000 are no longer eligible. Income and price limitations start in January, so if you want a tax credit for a Lucid Air, go buy it now.

The IRA does add a new element that could help get EVs to people who might not otherwise have considered one: a new $4,000 credit for used EVs with a sale price of $25,000 or less. This could rev the resale market, encouraging EV enthusiasts to purchase a new vehicle sooner because there will be more of a market for their used ride.

But even with more buyers considering EVs and car manufacturers racing to manufacture more each year, it will still be decades until the full fleet trunks over. That means who purchases the EVs available in the next few years will matter immensely for how successful those EVs are in reducing GHG emissions and increasing American resilience to volatile prices at the pump. Requiring would-be EV buyers to prove their income may, with a lot of extra paperwork, keep wealthier buyers out, but it doesn’t necessarily bring Super-Users (those Americans who drive the most and have to buy the most gas) in. Targeting a smaller number of credits at these bigger users, as I described here, would be a simpler and more direct way to get the most bang for the buck.

EVs are maturing, but they aren’t ubiquitous yet

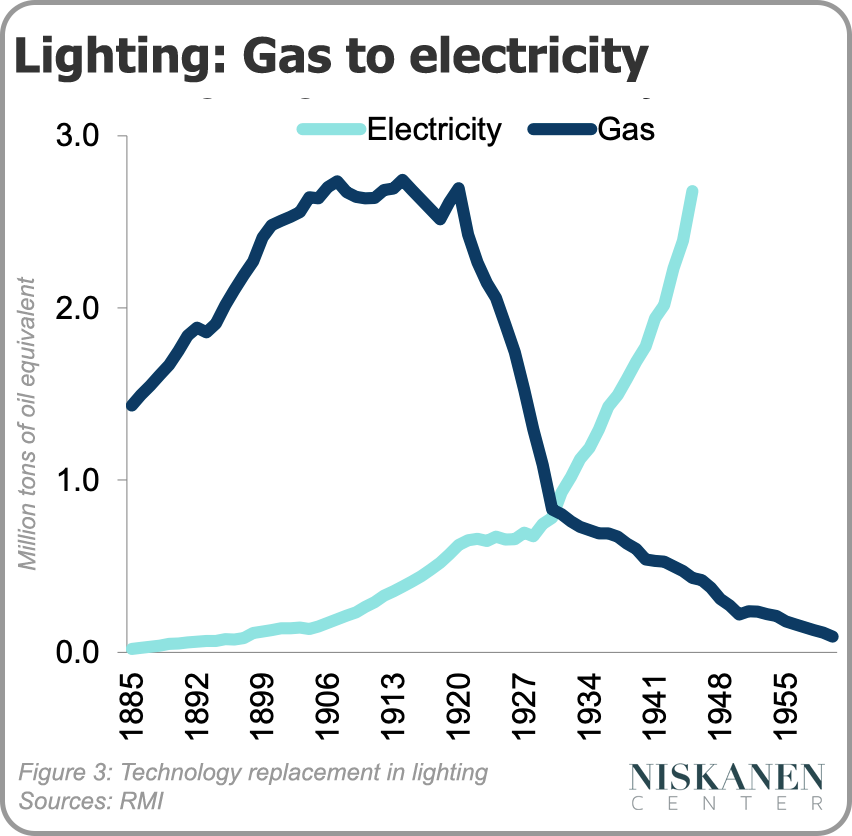

EVs may have reached a technology-adoption tipping point as manufacturers and buyers are becoming comfortable with them and appreciating the advantages they offer over older technologies, including being more fun to drive, cheaper to fill up, quieter, and less polluting. Experience in other countries suggests that once EVs reach 5 percent of vehicle sales, it will take less than a decade for them to almost completely take over the market. This is a common story when a new and better technology causes the rapid decline of the older technology, such as when electric lighting replaced gas (figure 3, below). We are somewhere on a similar curve for electric cars to replace gas.

In the U.S., EV sales have made up 5.4 percent of all vehicle sales so far in 2022, so we might already be on a rocket ship to most new vehicles being electric by 2030. If EVs have passed the hump in the S-curve, they may not suffer too much from a pullback in federal support and the industry may benefit from being shoved to diversify battery and critical-mineral supply chains away from their current dependence on China.

Then again, a summer reprieve on gas prices has recently cooled consumers’ desire. And COVID-induced supply chain woes are working against the young industry, limiting supply and driving up costs.

All things considered, the long-term outlook for EVs is excellent. But the next few years matter immensely for avoiding the worst risks of climate change. Fewer, better targeted, federal subsidies could be just the scalpel we need. But fewer, poorly targeted, federal subsidies would be a wasted opportunity.