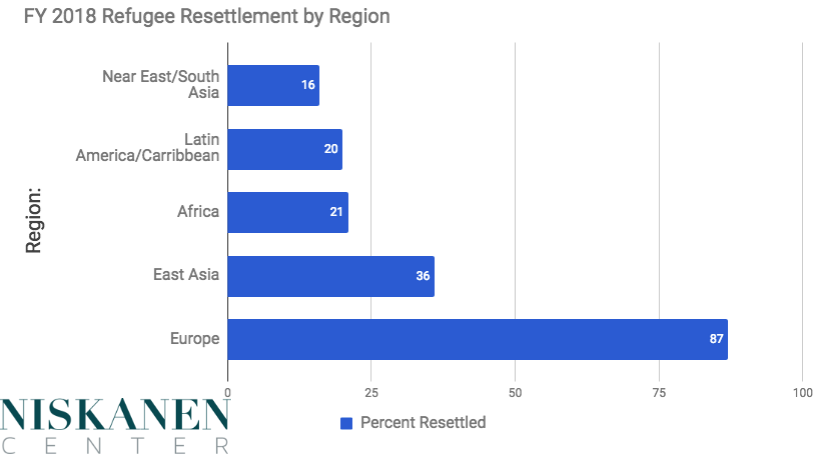

At the halfway point of fiscal year 2018, the Trump administration has resettled 87 percent of the European refugee cap, but other regions are lagging far behind. Just 21 percent is filled for Africa, 20 percent for Latin America and the Caribbean, and 16 percent for the Near East and South Asia, according to data from the State Department’s Refugee Processing Center. The U.S. has resettled just 23 percent of the overall refugee cap after six months.

Each year the President sets an overall refugee cap that includes regional allotments. President Trump set a 45,000 refugee cap for FY2018—the lowest in the history of the modern refugee program. Regionally, the ceilings are set at 19,000 from Africa, 5,000 from East Asia, 2,000 from Europe, 1,500 from Latin America and the Caribbean, and 17,500 from the Near East and South Asia.

Regional Resettlement Discrepancies Were Lower in Previous Years

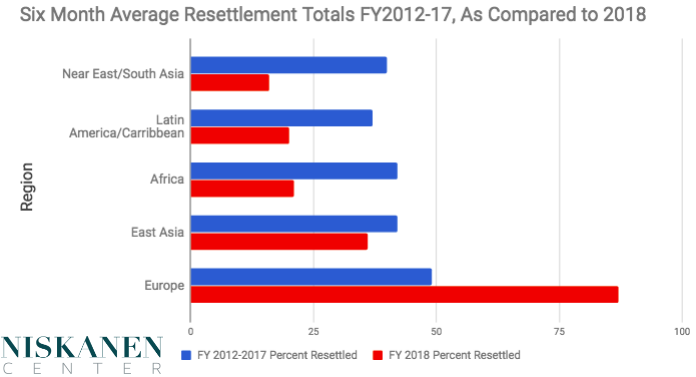

After six months, not only are the total numbers for refugees resettled in the country low, but they are unbalanced. Almost four times as many Europeans have been resettled than those from around the world, as a proportion of their respective caps; the Near East/South Asia, Africa, and Latin America/Caribbean regions are dramatically lagging in total percent resettled.

Why? The U.S. has resettled so few refugees from regions other than Europe because the administration has slowly—but deliberately—depleted resources away from certain regions. The situation is further exacerbated by the implementation of “extreme vetting” procedures for 11 mostly Middle Eastern and African countries alleged to be “high-risk nations.”

The stark difference in regional resettlement percentages is not normal. The average resettlement totals at the halfway mark for the last five years were much more evenly distributed, as shown in the chart below. For example, Africa has been cut in half yet Europe has almost doubled.

Impact of the Trump Administration on Refugee Processing and Admission

In a call with reporters in September 2017 when the refugee cap was announced, one administration official said, “I state unequivocally that that’s not our goal, to slow-roll it, and we have every plan to process as many refugees as we can under this ceiling.”

Despite this claim, it is evident that the Trump administration is subverting domestic and international refugee resettlement efforts, particularly in non-European regions.

First, cabinet officials are stymying the administrative refugee process by severely cutting personnel. Although prior administrations took the opposite tack, this year, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) deployed nearly half of its Refugee Affairs Division officers to the southwestern border and to asylum offices in the U.S., instead of refugee offices abroad. They were tasked with helping clear out the asylum backlogs—which continue to grow— instead of interviewing refugees.

Barbara Strack, former chief of the Refugee Affairs Division, said the move has had a dramatic effect on the ability of USCIS to conduct refugee interviews. Without interviews, potential refugees have no path forward towards resettlement.

This limited availability of officers has also handicapped the ability of Department of Homeland Security (DHS) officials to screen refugees. In the first quarter of 2018, DHS cut back on its “circuit rides”—travel of DHS officials to other regions to screen refugees—to just five locations, which is less than one-third the number of locations under the Obama administration.

To make matters worse, these circuit rides were shorter than the 6 to 8 week standard, staffed by fewer officials, and excluded the Middle East —the region with the largest resettlement shortfall. DHS added more locations in the second quarter—conspicuously leaving out any locations in the Middle East—but the rides were still shorter.

The effect is the ballooning of the resettlement bottleneck. Those refugees who already underwent many months of vetting and were ready to book their travel to the U.S. must now wait, potentially until their documentation and relevant information expires. Circuit rides keep the system moving; reducing or eliminating them paralyzes the system.

More ‘Enhanced’ Vetting

As the Trump administration downsized the refugee program as a whole, they specifically targeted nations they considered “high-risk” by instituting new, “extreme vetting” procedures for individuals from those countries. Prior to the additional reviews, the U.S. already rigorously vetted potential refugees. On average, the process takes 18 months, and even provides for an ‘Enhanced Review’ of Syrian refugees.

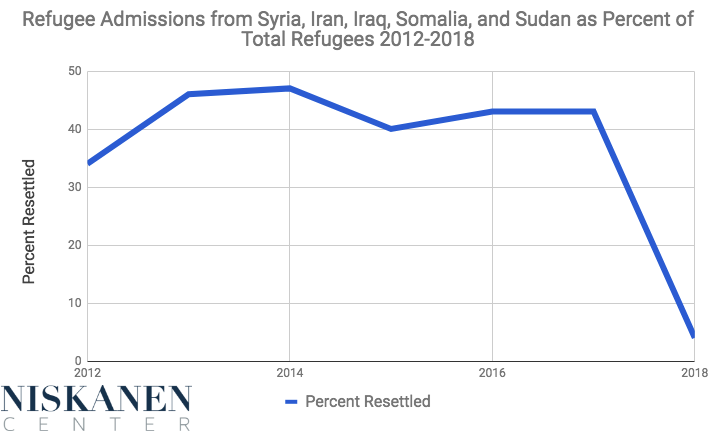

The administration admits it doesn’t know whether and to what extent its new, even more stringent measures will delay processing of refugees from the 11 countries flagged as high-risk. But we can get a sense by looking at trends for refugees from Syria, Iraq, Iran, Somalia, and Sudan, all of which were labeled “high-risk.” People from those five countries accounted for more than 40 percent (23,000) of total refugee admissions in FY 2017. This year, they are on pace to account for just 4 percent of admissions, or less than 900 in total.

Iraq, Iran, and Syria are in the Near East/South Asia region, which is the least-filled of any region. Somalia and Sudan are in the Africa region, which is about one-fifth filled. In short, the extreme vetting procedures hollowed out the capacity to process some of the largest refugee groups to the U.S. in the last decade.

2018 Will Likely See the Lowest Number of Resettled Refugees Since 1980

The administration has not sought in any meaningful way to quicken the glacial pace of admissions from non-European regions, or ensure that we fill the overall 45,000 cap, despite increased security measures.

It’s only the six-month mark of the fiscal year, and much could change in the next six months, if only the administration wanted things to change. But the trends—and the lack of any actions to change those trends—indicate that these discrepancies in resettlement are not a bug, but are a feature of the administration’s policies.