Three years ago today, President Obama announced a new executive action that would allow young illegal immigrants who came to the U.S. as children the opportunity to remain in the country and work without fear of deportation. The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), aimed to bring young immigrants out of the shadows but without granting legal status. President Obama, in announcing the new policy, said it would, “mend our nation’s immigration policy, make it more fair, more efficient, and more just—specifically for certain young people.” More than 660,000 undocumented immigrants have received DACA benefits in the first three years of the program, according to USCIS.

Critics were quick to decry the President’s use of executive power and his unwillingness to first bring the issue to Congress. However, the loudest criticisms of DACA came just last year as the rise of unaccompanied children at the U.S.-Mexico border made national headlines. The narrative for many anti-immigration conservatives was clear: by offering deportation relief, the Administration’s order incentivized a flood of young illegal immigrants to come to the U.S.

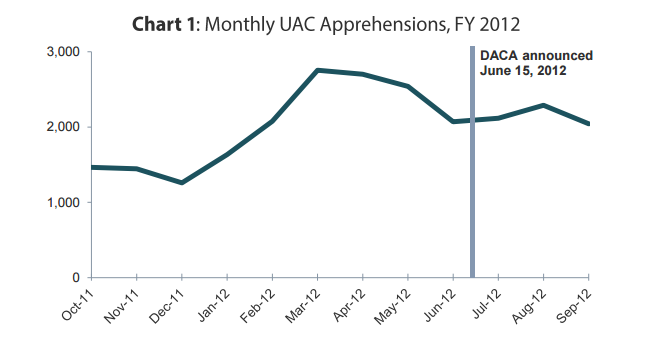

Earlier this year, the Niskanen Center’s Dave Bier published a study examining this oft-repeated theory that the DACA program was responsible for the 2014 rise in unaccompanied alien children (UACs). Bier’s study finds that the increase in UACs at the southern border began before DACA was even announced. Bier finds that more UACs entered the U.S. illegally in the three months before the DACA announcement than after it. Furthermore, the same number arrived in the six months prior to the announcement as the six months after. The chart below illustrates his findings:

Offering deportation relief will not produce a rush to the border, as many immigration critics claim. Fewer child migrants illegally came to the U.S. in 2014 than did in 2004. DACA, and other immigration policies, played less of a role than what was originally thought. The GAO reports that the main drivers behind the influx of children were violence in Central American nations, desire for economic opportunity in the face of severe poverty, and reunification with family already in the U.S. For more on the supposed link between DACA and the UAC crises, check out Bier’s study here.