What is the foundation of the conservative case against a climate policy? A new study by political scientists Constantine Boussalis and Travis Coan in Global Environmental Change examined 16,000 documents published between 1998 and 2013 by 19 conservative and libertarian think tanks in the climate business to find out. The authors conclude that opposition primarily stems from doubt that warming is a problem in the first place.

This has important implications for those of us hoping to replace expensive climate regulation with market-friendly alternatives. To wit, policy conversations are not going to get very far on the Right as long as skepticism about mainstream science dominates the debate.

Let’s start with the findings, which are quite interesting.

Conservative think tanks are the most pivotal players in this business. They are the parties most responsible for constructing and framing the skeptics’ narrative, which is subsequently amplified in the conservative echo chamber of blogs, op-eds, talk radio, Fox News, and social media activity. Conservative politicians who identify with the Right are moved accordingly. Conservative think tanks, according to sociologists Riley Dunlap and Aaron McCright, are the ‘‘’connective tissue’ that helps hold the denial countermovement together.’”

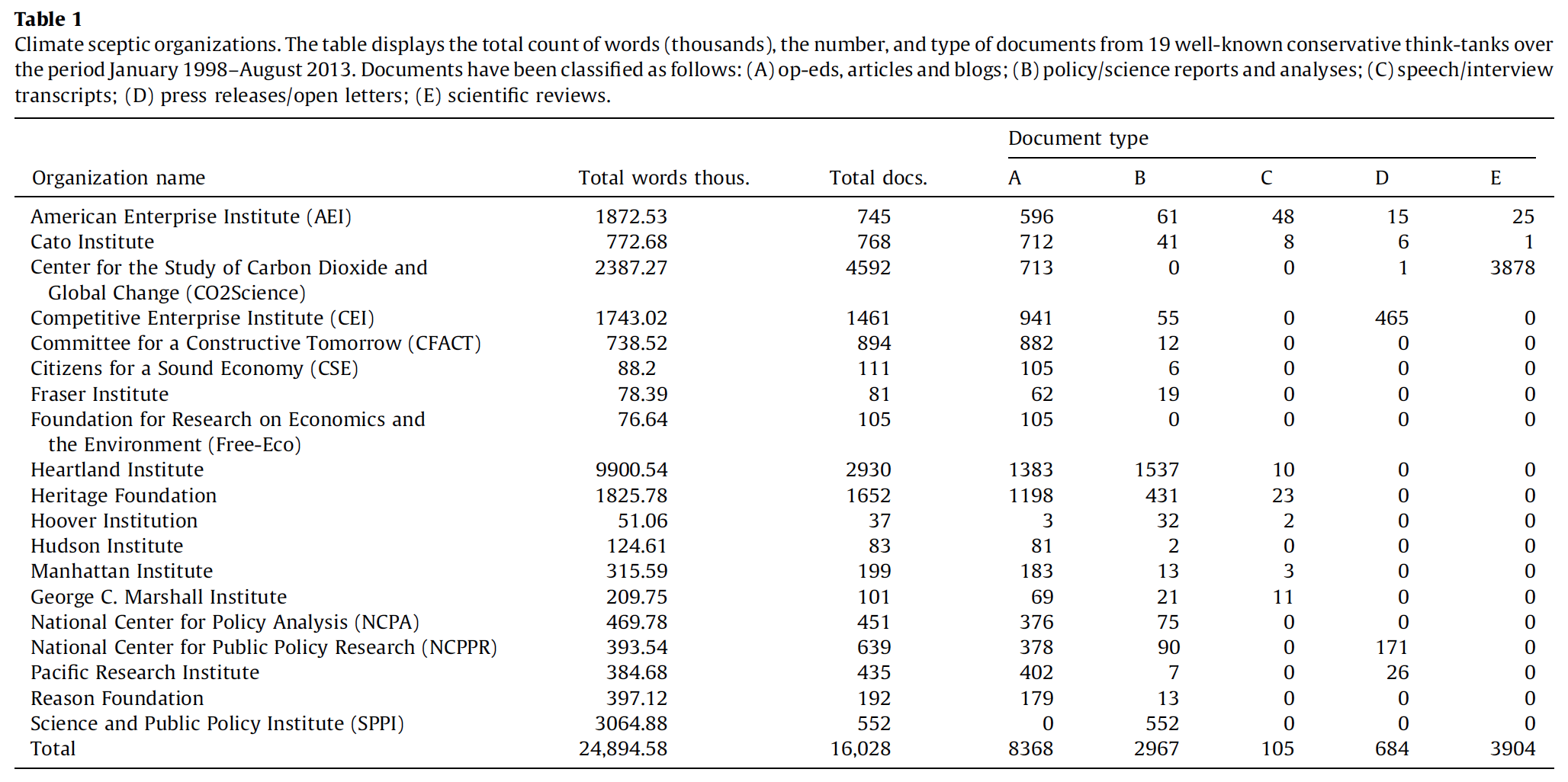

Who are the biggest players in that world? The dominant organizations (exact rankings depend on whether you’re interested in word count or publication count) are the Heartland Institute, Center for the Study of Carbon Dioxide and Global Change (C02Science), the Heritage Foundation, and the Science & Public Policy Institute (SPPI).

There is reason to think, however, that output of books is more important in this business than other outputs, and the big players here are the Competitive Enterprise Institute (CEI), the Heartland Institute, the Cato Institute, and the Marshall Institute. In a recent study, sociologist Riley Dunlap and political scientist Peter Jacques find that 92 percent of the books promoting climate skepticism are associated with conservative think thanks:

Although just one of many forms of media employed by CTTs [conservatives think tanks], books are especially important for reaching the conservative movement’s core constituency, wider segments of the public, and critical sectors of society such as corporate, political, and media leaders. Books confer a sense of legitimacy on their authors and provide them an effective tool for combating the findings of climate scientists that are published primarily in scholarly, peer-reviewed journals—at least within the public and policy (as opposed to scientific) arenas. Authors of successful books critiquing climate science often come to be viewed as “climate experts,” regardless of their academic backgrounds or scientific credentials, and despite the fact that their books are seldom peer reviewed. They are interviewed on TV and radio, quoted by newspaper columnists, and cited by sympathetic politicians and corporate figures. Their books are frequently carried by major bookstore chains, where they are seen (even if not purchased) by a wide segment of the public, many receive enormous publicity on CTT websites and from conservative and skeptical bloggers, and some are carried by the Conservative Book Club. In short, books are a potent means for diffusing skepticism concerning AGW and the need to reduce carbon emissions.

Interestingly, the volume of climate work from conservative think tanks has skyrocketed; from 203 documents between 1990 and 1997 to 16,028 documents from 1998–2013. As the planet heats up, so does skepticism from the Right.

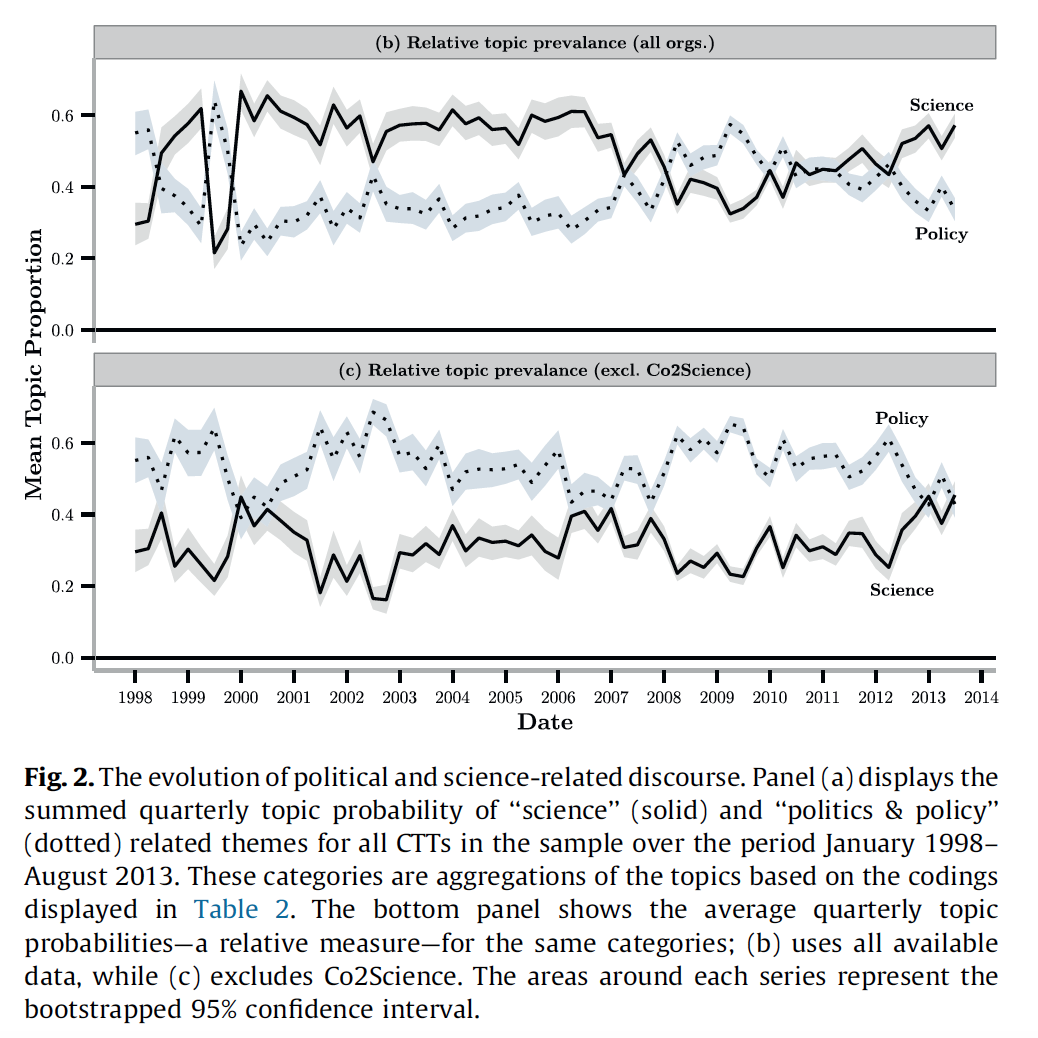

And what are these organizations saying? Whereas they once spent more time debating the utility of climate policy than attacking climate science, that trend has reversed over time.

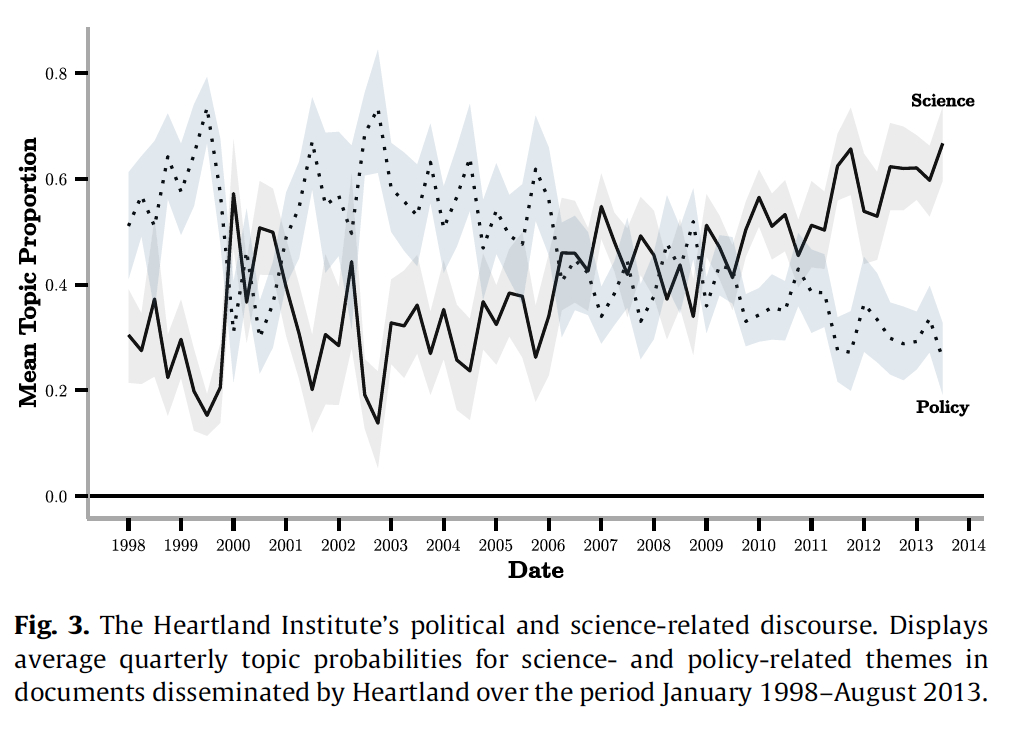

These trends can be clearly seen in an examination of Heartland’s climate work. Given that Heartland is probably the dominant player in this space, figure 3 speaks volumes.

The skeptics’ strategy of doubling-down on the science and deemphasizing policy arguments makes sense. Boussalis and Coan’s examination of the trends found in figures 2 and 3 suggest that skeptics are primarily engaged in countering mainstream narratives. As the evidence for climate change mounts and that evidence is marshaled for action, skeptics will counter by discrediting the science. Hence, the more that climate activists talk about the science, the more likely that climate skeptics will do likewise.

Moreover, empirical work by McCright et al. (2013) and van der Linden et al. (2015) suggests that agreement with mainstream science leads to support for climate policy action. This is not lost on Republican political analysts. In 2002, Republican pollster Frank Lunz wrote a memo to the GOP leadership and had this to say:

The scientific debate remains open. Voters believe that there is no consensus about global warming within the scientific community. Should the public come to believe that the scientific issues are settled, their views about global warming will change accordingly. Therefore, you need to continue to make the lack of scientific certainty a primary issue in the debate, and defer to scientists and other experts in the field […] Let me emphasize that while the economic arguments may receive the most applause at the Chamber of Commerce meeting, it is the least effective approach among the people you most want to reach — average Americans.

Now, the case for replacing the bulk of the existing subsidies and regulations addressing greenhouse gas emissions with a carbon tax—our preferred policy response to climate change—is quite strong regardless of how one feels about the underlying science. That’s because harnessing price signals and leaving it to market actors to decide whether, when, and how to reduce emissions is the least costly way of achieving emission reductions. Carbon taxes are the least costly policy option at hand because it’s nearly impossible to imagine a political scenario in which rapidly expanding state and federal interventions to reduce emissions are completely unwound by climate skeptics.

Still, disbelief of mainstream scientific conclusions presents a serious challenge for the Niskanen Center. Our policy agenda is a difficult sale to many on the Right given their conviction that global warming is—at best—a wildly overwrought problem and—at worst—a fairy tale told by a corrupted scientific community for those that want to shut-down modern industrial capitalism. For them, our argument means, at best, that carbon taxes are the least painful means towards a disastrous policy end. As long as they hold to the belief that mainstream climate science is a scam, the skeptics will fight until the rising tide literally washes them out to sea. Sooner or later, they believe, the weight of the satellite data and random variation in non-anthropogenic warming will end the panic and reverse political fortunes.

There’s some evidence to suggest that one need not directly confront the science to change conservative minds about the science. All that’s necessary is the presentation of market-friendly, pain-free solutions to the problem. Once conservatives are convinced that addressing climate change does not threaten their pocketbooks, endanger the free enterprise system, or expand government, they’ll hit the brakes on the motivated cognition that drives skepticism.

Perhaps. But the sort of polices that fit that bill in focus groups are the sort of policies that, by-and-large, fail to do enough to address the risks associated with warming. And they certainly don’t do enough in the way of mitigation to convince environmentalists to trade-off the current regulatory approaches and subsidies now anchored in law. Regardless of its economic merits, it’s hard to imagine the Right ever embracing carbon taxation as a conservative, pain-free policy option to address climate change.

Hence, if we want to replace climate regulations with price signals and bring the Right along for the ride, we need to directly confront climate science skeptics. While I have no illusions that doing so will win-over the climate gunslingers at Heritage, CEI, or Heartland, elite opinion leaders on the Right are another matter. There is good reason to think that opinion elites are more inclined to fairly weigh evidence than the conservative street, and as opinion elites go, so goes public opinion.

While one can remain skeptical about the science and still embrace carbon taxation, in reality, that’s too heavy a lift for many on the Right. Unless their conviction that modern physics is a scam is somehow broken, we’ll be stuck along the current path of expensive regulation.