This is the second in a series about recently-passed carbon pricing programs. The other three essays cover Washington, Austria, and Singapore.

In the first article of the series, we discussed how Washington state passed a new cap-and-invest law to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. But that’s just one state, and a “blue” one at that. U.S. lawmakers have not yet been able to pass an equivalent policy at the national level. Can a diverse nation successfully pass a federal carbon tax that applies across many distinct states or regions? Luckily, we need only look to our northern border for such an example.

2015: A campaign promise

In his 2015 campaign for prime minister, Justin Trudeau made climate leadership an important part of his Liberal Party platform. He pledged to re-engage Canada with international climate negotiations the country had shunned under Conservative leadership, and promised to put a price on carbon. Three of Canada’s provinces already had some form of carbon pricing, including British Columbia’s revenue-neutral tax that dates back to 2008. But no national system had yet been implemented.

The idea of raising revenue from greenhouse gas emitters was popular with the public: Three-quarters of Canadians supported a cap-and-trade system, and over half endorsed a carbon tax, both nationally and in their respective provinces. Even the fossil fuel industry supported the policy, with energy giants Shell Canada and Suncor Energy both publicly endorsing a carbon tax in the lead-up to the election.

Nevertheless, incumbent Prime Minister and Conservative Party leader Stephen Harper, hoping to defeat Trudeau in the election, attacked the carbon tax proposal as a tax grab that would “kill jobs” and “shut down the oil and gas industry.” Harper, who had been prime minister since 2006, had in fact proposed a national carbon tax of his own back in 2007. Later, that plan was scrapped in favor of a vow to use regulations, but nothing ever came of it.

Criticism came from the left as well. The New Democratic Party (NDP), a leftist party whose American corollary might be the Social Democrats or Bernie Sanders-style progressives, called the center-left Liberal plan “half-baked” and declared that output-based pricing was too friendly to industry. They preferred a different form of pricing – cap-and-trade. Provinces would be free to design their own systems and use the revenue for their own purposes. The main difference was that the NDP cap-and-trade system set GHG quantitative emission goals, whereas the Liberal plan set the price of carbon.

Trudeau’s Liberal Party proved to have their finger on the pulse of popular opinion. In the 2015 elections they won a narrow majority in the House of Commons (Canada’s main legislative body, similar to but more powerful than our House of Representatives), unseating the Conservatives for the first time in a decade. It was time for Trudeau to deliver on his promise.

2016: fleshing out the policy and building support

Trudeau set about launching his carbon pricing plan soon after taking office. His party created an ingenious “cooperative federalist” plan that offered similar terms to the nation’s provinces and territories. (Provinces are the Canadian equivalent of states. In this article, “province” will be used as shorthand for both province and territory.)

Trudeau’s plan sets a floor for climate action but leaves room for provincial differences and does not redistribute revenue across provinces. Each province is free to design a carbon pricing system that suits its particular needs, so long as it meets or exceeds the federal benchmark. Provincial governments that adopt a pricing system will receive all of the resulting revenue to spend as they see fit. So while the federal government is imposing a policy, it is giving each province the chance to control the implementation details and the money. Any province that does not choose to design its own plan will have to adopt the federal plan. In that case, it will forfeit control of the revenue. All revenue will still stay in the province, but the federal government will send it directly to households.

The federal plan includes two main components: 1) a “fuel charge” in the form of a carbon price that rises over time, levied on fossil fuels such as coal, natural gas, and gasoline, and 2) a performance-based price called an output based pricing system (OBPS) for industry. The price per ton of pollution is the same, but the output-based price only applies to emissions that exceed an industry-specific performance standard. This aims to protect against leakage, when an emitter chooses to move its operations out of the country rather than reduce emissions or pay the price. Leakage is a policy failure because it results in a loss of jobs in the country without reducing emissions, so policymakers want to avoid it. The achievable performance standard means to incentivize industries to reduce emissions per output of product through efficiency improvements or by switching to cleaner fuel inputs without scaring them off entirely.

In the fall of 2016, Trudeau announced that provinces would have until 2018 to choose between their own or the federal system. He also revealed a federal price starting at CA$10 (U.S. $7.72 in 2018) per ton, rising to CA$50 (U.S. $38.76) by 2022. Trudeau’s emissaries did intensive outreach across the country. By the end of the year, 11 of 13 provincial and territorial leaders had signed onto the plan, praising it as a positive step on climate action and a “good” design that didn’t step on local officials’ toes.

Oil-rich Alberta signed on in part in return for permission to build a pipeline to transport crude oil to the port in Vancouver. But the energy-producing province Saskatchewan pushed back on the policy. The province’s premier criticized the plan, saying, “This new tax will damage our economy.”

Members of the Conservative and NDP parties in the House of Commons also continued their opposition. Conservative legislator Ed Fast accused Trudeau of “taking a sledgehammer approach with provinces.” From the left, NDP legislator Linda Duncan criticized the proposed carbon price for insufficiently meeting the climate targets agreed to in the Paris agreement. Instead, she proposed a slew of individual regulations on fuels and industries.

2018: Parliament passes the bill

In June 2018, keeping in line with the timeline, Parliament passed the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act. The vote was strictly along partisan lines: The law received 158 yes votes from the Liberals, with one additional independent joining their ranks. All other parties voted no: 80 from the Conservatives, 29 from NDP, and 12 from smaller parties including the Green Party.

At the time, six provinces already had carbon prices in place or were on track to implement one by the end of 2018. In other provinces, the federal backstop would take effect starting 2019. Saskatchewan, however, launched a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of the Pollution Pricing Act, which Alberta, Ontario, and New Brunswick later joined. Ultimately, the Alberta and Saskatchewan Courts of Appeal (in 2019) and the Canadian Supreme Court (in 2021) upheld the law.

Today: A mix of provincial programs and federal backstop

Seven provinces adopted their own fuel charge and nine adopted their own industrial price, with the remainder taking the federal backstop. Put another way, six provinces implemented completely provincial systems (gray in Figure 1, below), three completely took the federal backstop (blue), and four have a mixed federal and provincial system (stripes).

Figure 1: Local plans and federal backstop carbon pricing in Canadian provinces

Source: Government of Canada

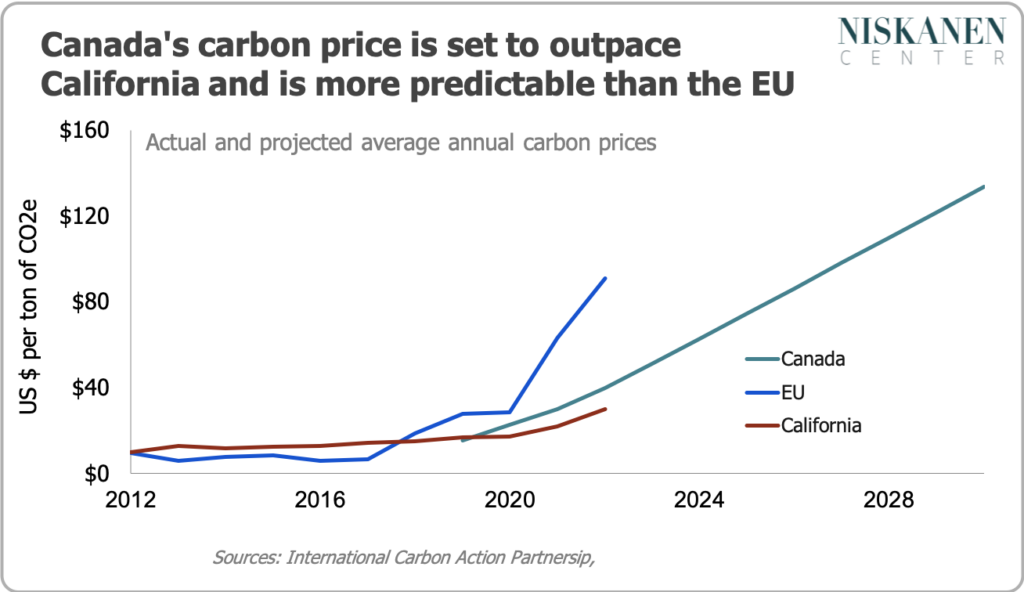

Raising revenue and giving it to Canadians

Nationally, revenues totalled CA$2.42 billion in 2019. That is expected to increase to CA$8.27 billion in 2022-23 as the carbon price rises. The federal government has set the floor price through the end of the decade. It will increase by CA$15 per year until it hits CA$170 in 2030 (teal line in Figure 2, below). That puts Canada’s carbon price on track to rise steadily higher than California’s (red line in Figure 2) Although the European Union’s price (blue line) is expected to be higher than Canada’s, it will be less predictable, since it varies depending on trading and economic conditions.

Figure 2: Carbon price paths in Canada, EU, and California

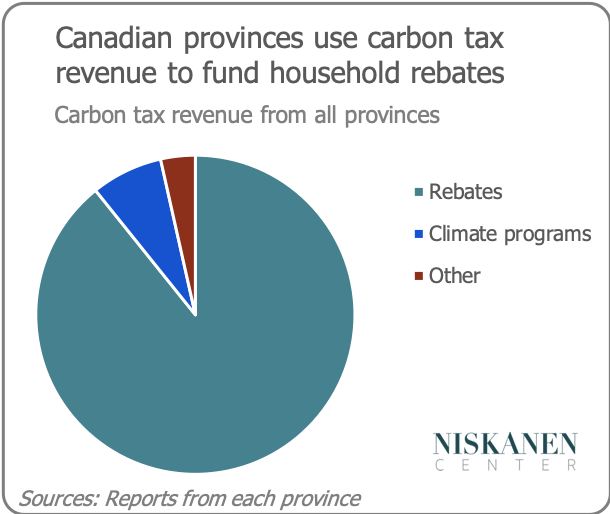

As shown in Figure 3, most provinces have chosen to give all or most of their revenue back to their people in the form of a rebate, with much smaller amounts going towards climate programs and other purposes. A whopping 80 percent of Canadian households get more money back in rebates than they pay in increased costs due to the carbon price. Only the top 20 percent of households end up paying slightly more overall.

Figure 3: Uses of carbon revenue in Canada

Ongoing debates

Some issues remain unresolved. Saskatchewan’s policy is one of them. In July 2022, the federal government rejected the province’s request to design its own fuel charge (it already has its own output-based pricing system). Premier Scott Moe has vowed to submit a new application to the federal government to “bring the provincial control of the entire carbon taxation regime into the province, away from the federal government.” The federal agency in charge, Environment and Climate Change Canada, has said it won’t look at new submissions until later in 2023.

Meanwhile, Conservatives are flailing for a way to convince voters that they take climate seriously. Former Conservative MP Lisa Raitt has said she likely lost her seat in 2019 due to the party’s opposition to carbon pricing. After the most recent election, almost three-fifths of Canadian voters said they wouldn’t vote for a party without a credible climate plan. In an attempt to convince voters that the Conservative party has a plan for climate change, party leader Erin O’Toole in August 2021 declared that the party supports carbon pricing. He proposed a conservative version, reducing the price to CA$20 and sending the money to a “low-carbon savings account” that individuals could tap for purchases such as a bicycle or efficient furnace.

But after losing again in the 2021 elections, the Conservative party reversed course once more and ditched its support of carbon pricing. Despite that, exit polls after the elections showed that the Conservatives didn’t lose votes as a result of supporting carbon pricing – in fact, 21 percent of swing voters were more likely to vote Conservative because of their new pricing plan. Nevertheless, this year the Conservatives selected a new leader who is vocally anti-carbon pricing and has not presented a climate plan. This Conservative opposition injects some uncertainty into whether the carbon pricing system will remain in place through the end of the decade. No matter the end result, the Conservative Party’s current lack of a climate plan has put it crosswise with voters.

What American policymakers can learn

Canada is similar to the U.S. in many ways. It is a geographically vast country with a federal government that serves as an umbrella over many regions with their own governments. It extracts substantial amounts of oil and gas. And its national politics are dominated by two parties, although it does have a few additional parties with some seats. But where the U.S. Congress made a failed attempt to pass a national carbon price way back in 2009 and hasn’t gotten close since, Canada successfully passed and implemented a carbon tax. What can U.S. policymakers learn from their northern neighbor?

1). Cooperative federalism: Feds set a floor and states decide what works best for them

The Pollution Pricing Act built upon the experience of several provinces that already had carbon pricing systems in place for years. Instead of imposing a single federal system and forcing all states to comply uniformly, the law allowed provinces to design systems that suited their particular economies. This addressed concerns from provinces that are prickly about federal overreach. But the federal floor still ensures a minimum level of climate action across the country.

The U.S. could learn from the Pollution Pricing Act’s “cooperative federalist” design. Like Canadian provinces, American states are economically diverse, with some blessed by wind and solar potential and others thriving on oil and gas extraction. Just as in Canada, many states have already had their own pricing systems for years – California has a cap-and-trade program, 10 Northeast states participate in a regional system, and Washington has now implemented a program it calls “cap-and-invest.” Congress could set a floor price, but respect the states’ expertise on their own economies.

2.) States keep their revenue

A key to Canada’s success was letting provinces keep their revenue and decide how to spend it. In Canada as in the U.S., carbon pricing discussions have been dogged by the fear that revenue generated in one jurisdiction would be spent in another. People and politicians in energy-producing areas worry they would be forced to subsidize their neighbors. Keeping revenues within a province helped ease this concern in Canada. Similarly, a plan that keeps all revenues within a state could ease some concerns in U.S. policy discussions by ensuring that places that pay more also get more revenue and that energy-producing states aren’t at a disadvantage relative to other states. As in Canada, such a design would counter any concern that the carbon tax is just a disguised way to grow the federal budget.

3). Trust in popular support

Though one might think carbon pricing enjoyed outsized popular support from Canadians, it is quite popular among Americans as well when framed as a corporate tax. Trudeau leaned in to public support, campaigned on it, and followed through. Elected officials on this side of the border could also lead on climate issues, knowing that voters want action.

- A 2020 Pew Research poll found that almost three-quarters of Americans support “taxing corporations based on their carbon emissions” including more than half of Republicans and nearly 90 percent of Democrats.

- Another 2020 poll by Yale University and George Mason University found that two-thirds of Americans support “requiring fossil fuel companies to pay a carbon tax and using the money to reduce other taxes (such as income tax) by an equal amount.” More than half of moderate Republicans support the idea and 36 percent of conservative Republicans do.

- Support among younger Republicans is high. A 2019 poll by the Climate Leadership Council found that a whopping three-quarters of Republicans under 40 years old support a carbon fee-and-dividend system that taxes fossil fuel companies and sends the revenues to the American people via a quarterly check.

The bad news is that when a carbon price is framed as a cost to individuals, support drastically decreases, even at low prices. A 2021 poll by the University of Chicago found that half of Americans support a carbon fee that would increase their monthly energy bills by just $1. While support dwindles for monthly bill increases over $10, interestingly, it remains somewhat inelastic as the price increases further. Around one-third of Americans are steadfast supporters of a tax, even as the price goes up: 35 percent support a carbon fee that would raise their bills by $10 per month; 37 percent at $20; 32 percent at $40; 27 percent at $75; and 31 percent at $100.

4). Emphasize benefits, not costs

This brings us back to a lesson learned from Washington state: Voters want to hear about what they are going to get, not what they are going to pay. Trudeau’s allies emphasized the money that provinces and voters would get back, not how high the carbon tax would go. A federalist design plus a concerted messaging effort to let voters know the money is all coming back to their state, and possibly directly to them via rebates, could be effective here, too.

5). Conservatives need a credible position on climate change

Republicans might be concerned about Conservatives’ experience in Canada. By spending a decade vociferously attacking carbon pricing, the Conservatives lost credibility with voters who wanted them to do something on climate change. Now they are struggling to find a conservative climate position and convince voters it is an issue they genuinely care about. American Republicans should be leery of painting themselves into a similar corner. Republican voters are increasingly calling for conservative climate leadership (more on this below). Luckily, Republican leaders have not attacked carbon pricing in the same way that Canadian Conservatives did. In fact, a number of notable Republicans have voiced support for carbon pricing, including Rep. Brian Fitzpatrick (PA), 19 members of the Utah Legislature, and others. Republicans could also embrace a compelling abundance agenda, championing policies to increase the supply of clean, affordable, made-in America energy and products, to convince voters they are serious about climate, energy resilience, and American jobs.

6). A performance-based price for the industrial sector might be easier to tackle before a tax on transportation fuels

Despite the carefully federalist approach and the regional revenue protections, the fuel charge still faced stiff political headwinds in Canada. In contrast, the price on industrial pollution was less controversial, with even more conservative leaders in support.

Perhaps a performance-based price on industry would be less contentious here, too. An industrial price designed similarly to Canada’s, where facilities only pay for emissions exceeding an achievable level of efficiency, would pair well with a carbon border-adjustment mechanism. Lawmakers on both sides of the aisle could support a mechanism that drives higher performance in domestic industries while dealing fairly with international competition.

A path forward in the U.S.?

Canada was able to pass a carbon tax on a majority vote, an option that might not be available under current Senate rules. Nonetheless, American Republicans are in a more favorable position than Canadian Conservatives in terms of their room to maneuver on carbon taxes and energy abundance policies. Republicans have not been publicly attacking carbon taxes for the past decade, so they could conceivably answer rising demands amongst their voters, especially younger voters, for a conservative climate plan by designing their own carbon tax. That tax could adopt a cooperative federalist design, setting a federal floor but leaving the details and the revenue to each state and recycling all revenue back to the state from whence it came. Alternatively, Republicans could take the less controversial page out of Canada’s book and pass an industrial performance-based price. Or they could embrace an abundance agenda that would be good for energy production and prices and good for the climate.