Can we put everyone to work? In a way, it seems like an odd time to be asking the question. After all, the official unemployment rate is at a 50-year low and the U.S. economy has added jobs for a record 110 consecutive months.

Still, broader indexes show much greater labor market slack. Those indexes include some 4.4 million people who are working part time but would like to work full time, and an additional 4.4 million who say they want a job, but are neither working nor looking. What is more, the labor force participation rate, even for prime-age workers, is not yet back to its prerecession level and is even farther below the rates of the 1990s.

But how to do it? How to get more people to work – and better yet, at a living wage? In what follows I will discuss four proposals. The first two – guaranteed jobs, from the left, and work requirements, from the right – I view skeptically. The other two are wage subsidies and basic income. I see those as more promising, and more promising still if combined.

Guaranteed Jobs

A job guarantee (JG) is one of the three main pillars of the Green New Deal, along with clean energy and universal health care. Under a JG, anyone who wanted could get a full- or part-time job just by showing up. They would be directly employed by state or local governments and nonprofit organizations, while the cost would be borne by the federal government. The jobs would pay a living wage of something like $15 per hour, plus full benefits. Jobs would be created to match workers’ skills and places of residence, so they could start immediately without retraining or relocation.

According to two detailed descriptions [1] [2], guaranteed jobs would be taken up by some 10 to 15 million workers, even with the job market as tight as it is now. Including wages, benefits, payroll taxes, and supplies, the total cost per job would be something like $45,000 to $56,000. The gross cost to the federal budget would be $409 billion to $543 billion per year, some 9 to 11 percent of current federal spending. The net cost could be substantially lower because of taxes paid by workers and budget savings on existing welfare programs, however.

Nevertheless, although the cost of a full job guarantee, even with offsets, would make such a program a hard sell in Congress, cost is not the biggest reason I am skeptical. Three things particularly concern me.

First, even though guaranteed jobs would be designed not to compete directly with the private sector, a JG would still be disruptive. Private employers would lose workers if they did not match a job-and-benefit package worth some $20 per hour. JG advocates are confident that private employers have enough slack to raise wages without cutting employment, but I am not so sure. JG jobs would not only offer good wages and benefits, but also, as advocates promise, they would be more accommodating than many private sector jobs to workers’ personal schedules, family needs, and disabilities. A large outflow from private employment to guaranteed jobs could raise the cost of the program sharply.

Second, I think advocates overstate the ease of creating 10 to 15 million meaningful new public service jobs. To avoid competing with the private sector, they could not be jobs in hotels or factories. They could not require advanced skills or investments in heavy equipment, which would mean JG workers could play a limited role in projects like replacing aging bridges or building green energy infrastructure. When we read advocates’ descriptions of JG jobs, they talk about things like teachers’ aides, recycling, and planting trees on vacant lots. How many workers could be absorbed in such jobs before they became mere make-work?

Third, many of those who remain out of work in today’s booming economy are, almost by definition, among the “hard to employ.” Those include people with criminal records, unstable housing, substance abuse issues, family situations that interfere with regular work schedules, and borderline mental and physical conditions that fall short of full disability but still create problems on the job. Programs that try to find work for the hard-to-employ are not a new idea. Many existing programs are well run. Still, their experience shows that lasting success requires intensive, one-on-one casework to help with things like soft job skills and support with personal issues. Even then, success rates are far from 100 percent. The leading JG proposals do not, in my view, come close to budgeting enough for administration, counseling, and support services.

Work Requirements

Although the issues just discussed make me skeptical of guaranteed jobs, I am no less skeptical of the leading conservative alternative – work requirements on welfare recipients. Welfare reforms of the 1990s already imposed work requirements on most recipients of cash welfare. The current administration now wants to extend work requirements to noncash programs such as SNAP, Medicaid, and housing assistance.

A recent report from the Council of Economic Advisers claims that the welfare reforms of the 1990s prove that work requirements can increase employment and reduce dependence. I see two reasons to doubt such confidence.

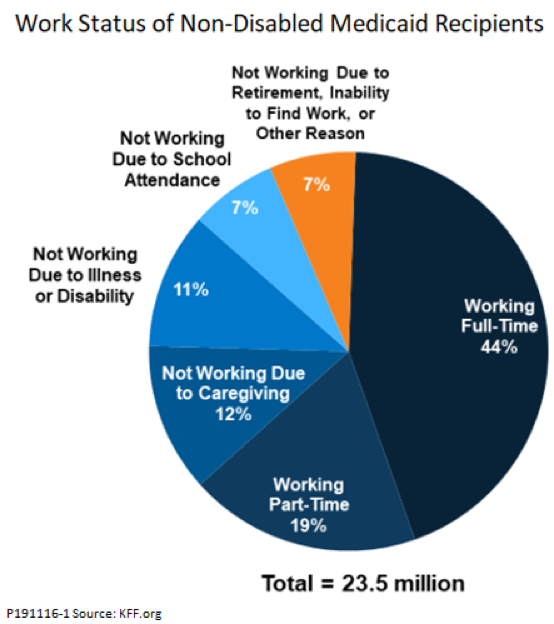

For one thing, backers of work requirements assume there are many nondisabled welfare recipients who are able to work, but who choose not to. The data show otherwise. They show that a majority of nondisabled welfare recipients already work or face serious barriers to work. The following chart from the Kaiser Family Foundation shows data for Medicaid recipients. The figures for SNAP, housing assistance, and other programs are similar.

As the chart shows, well over half of Medicaid recipients are already working, and nearly half work full time. Some 12 percent are not working because of caregiving responsibilities and another 7 percent because they are in school. Although the chart excludes people who have qualified for Social Security disability programs, 11 percent even among the officially nondisabled cite illness or disability as their reason for not working. That leaves just a sliver who fall into the category of “not working but able to work.”

A second problem is that the kind of work requirements that conservatives favor are not, in practice, very work-friendly. They often place unrealistic burdens on beneficiaries, such as detailed record keeping, frequent verifications, and unrealistic allowances for family needs or irregular work schedules. Administrative lapses are often punished with extended lockouts from benefits. Furthermore, these programs – like some JG proposals – offer inadequate personal assistance to the hard-to-employ, leaving it up to them to find work or training and to deal with personal barriers to work.

In the end, then, many people who ought to qualify for assistance fail to do so. Many who are pushed off welfare rolls do not find work. On balance, work requirements trim welfare rolls but increase poverty. Cynics say that is the intended outcome.

Wage Subsidies

Progressives promise jobs in the public sector. Conservatives propose using the stick of work requirements to push people into private-sector jobs. Wage subsidies fall somewhere between these alternatives. They focus on private- rather than public-sector jobs, but they use a carrot rather than a stick to encourage employment.

By far the largest wage subsidy program is the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). In existence since 1975, it has earned wide bipartisan support. Liberals like it because it raises 6 million families out of poverty each year. Conservatives like it because it encourages work and self-sufficiency. Ronald Reagan called it “the best anti-poverty, the best pro-family, the best job creation measure to come out of Congress.”

The amount of wage subsidy offered under the EITC varies both with income and the number of dependent children. For the lowest-paid workers, it provides a bonus of 35 to 45 cents for each dollar earned. Once earnings approach the official poverty level, the subsidy is gradually phased out. Benefits are paid in a lump sum, once a year, as a refundable tax credit.

Basic Income

Successful though it is, the EITC has its critics. Some point out that the once-yearly payment makes budgeting difficult for low-income families and dilutes the program’s incentive value. Others note that it does little to help people with no children and nothing to help those who cannot work or cannot find work.

One way to meet those criticisms would be to pay a Universal Basic Income (UBI) to everyone regardless of whether they worked or not, and regardless of the number of dependent children. For example, the Freedom Dividend proposed by Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang would give every adult citizen a payment of $1,000 per month. Many other UBI variants have been discussed, including some with conservative backing.

How would a basic income affect work incentives? It might at first seem that a UBI would discourage work. After all, you might think, if you give people money whether they work or not, why would they work? In reality, though, the effect on work incentives depends on what a UBI would replace. Current means-tested welfare programs like TANF, SNAP, and housing vouchers, which reduce benefits for each dollar a person earns, have a strong negative effect on work incentives. If a UBI replaced those, as Yang’s Freedom Dividend and many other versions do, the net effect would be to encourage work. The spending saved on those other forms of welfare could go a long way toward paying for the UBI itself. (See here for more on the incentive effects of a UBI.)

Toward an optimal pro-work policy

Returning to the question we began with: Can we put everyone to work, or can we not?

Probably not everyone, or even all who say they want to work. Even the costly option of guaranteed jobs for all would likely fail many of the hard-to-employ, and in the process of trying, it would risk seriously disrupting the private sector.

Imposing work requirements on recipients of existing welfare programs is not going to do the job, either. In practice, work requirements do manage to trim welfare rolls, but many who lose benefits fail to find work and only slip further into poverty.

Wage subsidies are more promising. In the form of the EITC, they raise many families out of poverty, and most studies suggest that they cause many people to take jobs who would otherwise not work at all. However, structuring the EITC as an annual lump-sum tax refund reduces its incentive value, and the program does little for families without children.

A basic income would help those without children and would increase work incentives at least to some degree, provided that it replaced the “welfare traps” inherent in existing, means-tested programs.

But could we do better still? There is no logical reason to view wage subsidies and basic income as either-or alternatives. Why not combine them? Why not a wage subsidy that would give a bonus to all low-income workers, as the EITC does, with a UBI that would provide a minimum benefit to everyone, including children? This approach could combine the best pro-work features of both policies while more effectively combating poverty than either could do alone.

Based on a presentation to the Economic Club of Traverse City, MI, November 15, 2019. Follow this link to view or download the slideshow of that presentation, complete with additional graphics.