States now have the option to attach work requirements to Medicaid for the first time in the program’s 52-year history following new policy guidance issued by the Trump administration.

The guidance prevents work requirements from being applied to the elderly, individuals with disabilities, or pregnant women, but that doesn’t make the policy shift any less grave. By definition, work requirements in Medicaid will result in otherwise eligible individuals being denied access to health coverage due to their work status or obstacles to providing work verification; if not, the requirements will be toothless. For anyone unable to comply due to illness or because they are caring for a loved one, the result is a troubling Catch-22 in which they will have to rid themselves of sickness before becoming worthy of treatment.

Yet perhaps the most troubling unintended consequence of this policy move will be its impact on efforts to address the opioid abuse crisis that has swept the country.

Medicaid Is a Key Tool for Fighting the Opioid Crisis

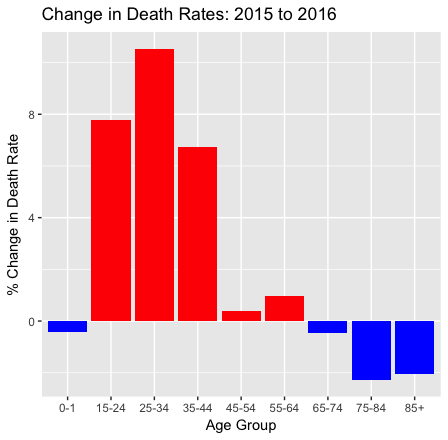

At least 66,000 people died from drug overdoses last year, up 17 percent from the year prior. The staggering increase in death rates among the working-age population at the center of the crisis is so significant that it has caused a measured decline in total U.S. life expectancy for the first time in generations.

via The Incidental Economist, based on CDC data.

Perhaps equally disturbing has been the relative lack of urgency in the federal government’s response. To the current administration’s credit, in November of last year the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) relaxed barriers to state implementation of substance abuse programs, immediately approving two such waivers for demonstration projects in New Jersey and Utah. That said, the depth of the opioid crisis demands a more full-throated response, for which the addition of work requirements to Medicaid are at best a distraction, and at worst actively counterproductive.

Since the passage of the Affordable Care Act, Medicaid has transformed from a health insurance program primarily for children, pregnant women, and individuals with disabilities into a more general insurer of last resort for households below 133% of the federal poverty-line. In turn, it has become the key vehicle for delivering substance-abuse and rehabilitation services to populations at risk of opioid abuse and overdose.

As a January, 2017, article in the American Journal of Public Health explains,

Historically, [Substance Use Disorder] treatment services have either not been covered at all under private and public insurance plans or have been limited through the use of higher copayments, annual visit limits, and placing medications on higher tiers. As a result, many Americans in need were unable to access affordable SUD treatment. The ACA has dramatically changed that picture. … The ACA allows an arsenal of tools for states to not only address use disorders for all substances, but the opioid epidemic in particular. Many states have taken full advantage of this arsenal, and although the epidemic continues, it would arguably be worse without these reforms.

Medicaid is central to this arsenal, with roughly 3 in 10 people with opioid addiction receiving coverage through Medicaid or CHIP. Given the age and income profile of the addicted population, that ratio could be higher still.

Even some states which have not embraced the ACA’s full Medicaid expansion have nonetheless recognized the importance of Medicaid as a delivery vehicle for substance-abuse treatments. Utah, for instance, recently expanded Medicaid to individuals without dependents for the first time in the state’s history, with a focus on their chronically homeless and drug-addicted populations.

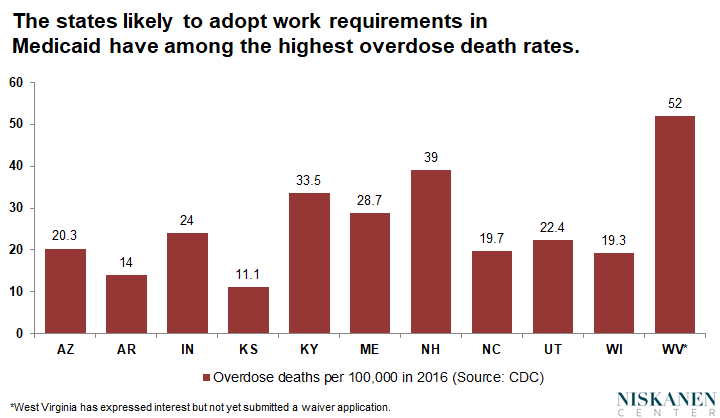

It’s worrying, then, that of the 10 states that have requested waivers for work requirements in Medicaid, eight have overdose death rates roughly equal to or significantly above the 2016 national average (19.8 per 100,000), including outlier states like New Hampshire, Maine and Kentucky. As of November 2017, West Virginia is also considering adding work requirements to the Medicaid program. West Virginia has the nation’s highest opioid-death rate at 52 per 100,000 people in 2016. Not only are these some of the last places in the country that should be experimenting with work requirements in Medicaid — if anything, they should be combining lower barriers to Medicaid access with an aggressive opioid abuse outreach program.

Medicaid Work Requirements in Practice

Advocates of work requirements in Medicaid have plausibly argued that employment, and “community engagement” more broadly, is an essential ingredient to a successful recovery. This paints a rosy picture of an opioid addict receiving coordinated case management, in which an initial detox therapy is followed up by a holistic rehabilitation program interspersed with small but meaningful acts of community service.

In reality, Medicaid work requirements are unlikely to look anything like this. Take Kentucky, the first state to be approved for Medicaid work requirements as part of a more comprehensive Section 1115 waiver. Kentucky does not even currently offer coordinated case management within Medicaid, and yet, according to their application, they intend to roll out a graduated system that will require all able-bodied Medicaid recipients to engage in 20 hours of work or community service per week after the first year of being in the program.

While this may sound benign, it must be reconciled with the fact that opioid addicts have a relapse rate surpassing 90 percent. In 2016, Kentucky had the sixth highest death rate from opioid overdose of any state. Despite being an expansion state, their Medicaid program currently fails to provide for partial hospitalization for those with overdose risk, nor cover all three of the prescriptions (methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone) known to treat opioid abuse disorder and decrease the probability of relapse.

With these facts in mind, consider someone who lasts one year in Kentucky’s program before falling off the wagon. Failure to meet (and properly report) work hours would result in a suspension of benefits until the member satisfied the requirement for a full month. The member could also be subject to small premiums, which, if unpaid, would result in being locked out of the program for six months until the next enrollment period, unless they successfully pass a patronizing financial literacy test.

Worryingly, some are hoping for Kentucky to be a model for the Medicaid writ-large, in a similar way welfare-to-work programs were tested through waivers in Wisconsin and elsewhere before being federalized in the 1996 welfare reform. Conservatives ought to take a hard second look at the ways welfare reform failed before reproducing the same unintended consequences in Medicaid.

The Dangerous Political Economics of Medicaid Work Requirements

According to a statement released by Seema Verma, the administrator of CMS, the decision to permit work requirements in Medicaid came “in response to states that asked us for the flexibility they need to improve their programs and to help people in achieving greater well-being and self-sufficiency.”

Yet it doesn’t take a deep appreciation for Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs to understand why having one’s basic health in check is an important prerequisite to finding stable employment, not the other way around. Consider evaluations of Medicaid expansions to date, which reveal greater health coverage increases employment and job search in newly eligible populations, without the need for government compulsion.

Instead, CMS’s policy decision bares all the marks of the on-going Republican effort to roll back the Affordable Care Act through piecemeal executive actions. In this case, work requirements provide a lever for red states to scale back the expansion of Medicaid to low-income adults by adding new administrative barriers to enrollment, potentially freeing up significant budget resources for states.

Ron Haskins of the Brookings Institution, in a classic case of “saying the quiet part loud,” admitted as much at an American Enterprise Institute event last October. “There is an entirely different motivation for governors in Medicaid,” noted Haskins, himself a veteran of conservative welfare policy and tentative proponent of work requirements in Medicaid. “For every person they get off Medicaid they’re going to save a lot of money. It’s not like food stamps.”

“Self-sufficiency,” a wise person once said, “is just another word for poverty.” But for the Republican party it’s also become code for stripping the poor of public benefits — and for wholly political reasons. The difference this time, however, is that they also run risk of perpetuating the most severe public-health crisis facing the United States since the AIDS epidemic.