Like a number of commentators on the right, Veronique de Rugy is not a fan of the border adjustment tax, and her concerns are fairly representative of conservative and libertarian resistance to the proposal. She offers three related grounds for opposition. First, the border adjustment tax raises revenue in the short term and, de Rugy suggests, this gives away the game.

They are preemptively capitulating to the Left’s premise that pro-growth tax cuts are something that must {be} “paid for” through increases in other taxes instead of with spending cuts or by simply letting the economy grow and bring overall tax revenue up along with it.

The idea here is that, since the left is inclined to support tax increases, conservatives and libertarians should oppose any and all tax increases on principle, only capitulating when they lack the political power to stop them. The problem with this line of reasoning is that it means all tax increases will come when libertarians, and economic conservatives in general, have the least power to influence policy design. It cedes any control over the tax structure, which is at least as important as the tax rate.

Indeed, de Rudy’s second objection, that the left is already salivating over raising the the border tax rate, illustrates how important this is in practice. She is alarmed by what Bill Gale of the Brookings Institution had to say at a recent Tax Foundation event:

[Gale] said “It essentially makes the government a shareholder in every corporation in America. The government shares all the losses, and it shares all the profits.” …

But then it gets better. Gale then reiterated his call for a much higher rate than the Republican plan’s 20 percent. And as he said at the 45:33 mark, “If something is non-distortionary, you should tax the hell out of it.” That has the merit of being honest and transparent.

Yet, whether we should have a high or low rate on a minimally distorting tax structure is precisely the argument we want to be having. Consider what the alternative suggests: that we ought prefer a tax structure which does more economic damage to the country so that our political opponents will be less willing to use it. Even if that tactic were to in some sense “work,” it leaves us with less revenue, more debt, and greater economic distortions. We should seek policy that improves the range of outcomes rather than simply thwarting the other side from achieving their objectives.

There is little reason, moreover, to believe that this tactic will work. This becomes clear in de Rugy’s third objection to a border adjustment tax: that it is similar to a VAT and therefore the first step towards European-style socialism.

…if the power is in the hands of a future President Elizabeth Warren and her Democratic Congress, nothing will stop them from for resolving [a potential] WTO challenge by ending the wage deduction and turning the border-adjusted tax into a VAT. A VAT on top of our current individual income tax is a development that the Left and those dreaming of more revenue for the government have long fantasized about in order to finalize our transformation into a big-government European-like nation. When that happens we will have the Republicans to thank for it.

But where is the evidence that the growth of government is checked by tax revenue, or that the difference in the size of government spending in the United States vs Europe comes down to tax structure?

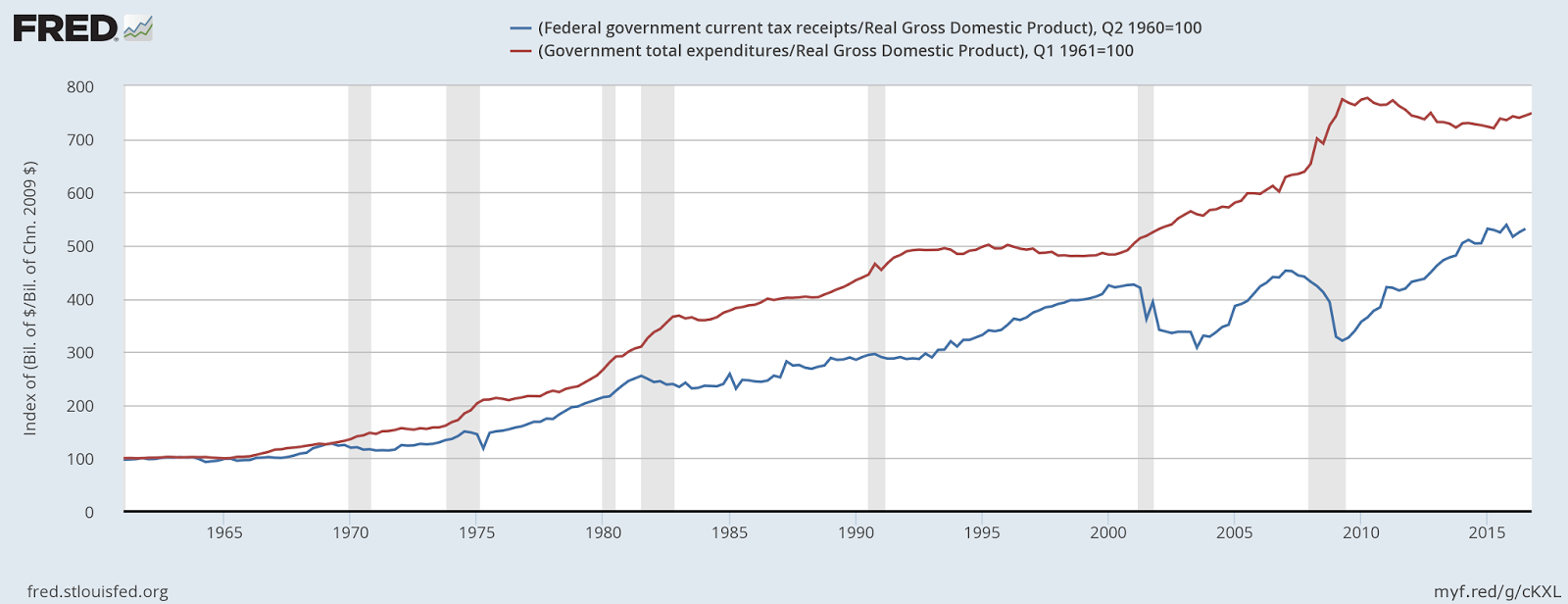

Historically, taxes and spending as a fraction of GDP have diverged during recessions and periods of political profligacy. They have converged, however, during periods of austerity.

In short, when the political will exists to balance the budget, tax revenues rise and spending growth is restrained. When the will is not there, revenues fall and spending rises. Overall government spending is not rising because we refuse to cut taxes. Indeed, cutting taxes, if anything, fuels spending growth. Spending is rising as a part of a long run trend to increase government social insurance in all advanced economies.

This trend is not limited by tax policy. It is limited by the degree of ethnic and religious homogeneity. European nations have larger governments not because of their tax policy, but because they tend to speak the same language, share the same traditions, and worship in the same church. We can argue whether the restraint on government spending in the United States is because of distrust for those not like us or a genuine respect for ethnic pluralism and communities to define their own destiny, but it is not because we have starved the beast using a tax structure so inefficient and ruinous that even big government leftists are afraid to employ it.