The idea of Universal Basic Income (UBI) is for the government to transfer a lump sum to every individual or household, regardless of how much they earn on their own. As Matt Yglesias recently described it, it’s essentially a plan to make social security universal. Proponents argue a Basic Income will raise workers’ bargaining power, reduce poverty, and provide subsistence after robots take our jobs, all while condensing the current potpourri of welfare programs down to a single check in the mail.

Fantastic. The only problem is that, as it’s currently being discussed, UBI comes across as expensive. Very expensive.

The representative proposal is $10,000 per person per year. That implies an over $3 trillion dollar price tag. Writing in the New York Times, Eduardo Porter points out that, even if cut in half to $5,000, a UBI would still cost “as much as the entire federal budget except for Social Security, Medicare, defense and interest payments.”

Cost estimates like this are damning to the UBI cause, and hurt its potential of ever being enacted. Switzerland just rejected a UBI proposal in a landslide referendum, largely because of confusion over how it would be funded.

But this doesn’t have to be the case. The reason is a constant source of frustration for economists trying to assess transfer programs of all types. Namely, universal transfer programs like a Basic Income cannot be analyzed outside of the tax system that pays for it.

Taxes and transfers are two sides of the same coin. You might as well call taxes negative transfers, so to propose a lump sum transfer like UBI without an explicit discussion of how it’s financed only tells half the story. On Twitter, the economist Nick Rowe was a bit more blunt.

Any definition of "Basic Income" that speaks only of transfer payments and ignores the tax system is a stupid definition.

— Nick Rowe (@MacRoweNick) June 1, 2016

Indeed, adding in the tax system is necessary for conceptual clarity. And one of the first things it clarifies is how every working UBI proposal is really, at heart, a Negative Income Tax (NIT) proposal in disguise.

Universal Basic Income v. Negative Income Taxes

The NIT, popularized by Milton Friedman, is an extension of the progressive tax system into negative territory. Just as someone making lots of money pays a higher tax rate, those below the poverty line would pay an increasingly negative tax rate—which is to say, the IRS would pay them.

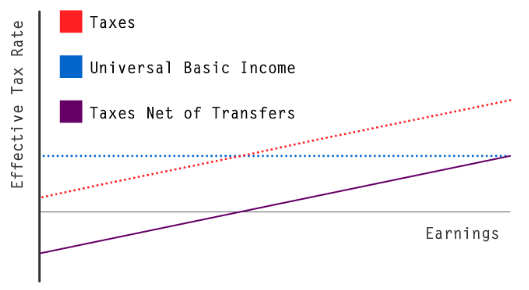

A simple diagram makes it easy to see why a UBI with flat tax is functionally equivalent to an NIT. I’ve ignored complications like deductions and payroll taxes, and treated the United States as having a linear tax structure, rather than a step-wise structure with discrete tax brackets. This is just to make it easier to represent the tax and transfer system holistically, for illustrative purposes, although the basic point would still hold with those elements added in.

The flat tax is represented by the red line, rising as a function of earnings, while the blue line is the UBI, i.e. a lump sum transfer payment to every individual in the economy, independent of earnings. Summing the two gives taxes net of transfers, the purple line. From this, it becomes trivially obvious that all a UBI really does is shift down the intercept of the net / effective tax structure.

When UBI advocates are faced with the challenge of a $3 trillion dollar price tag (here, the area beneath the blue line) they usually point out that it could be paid for by higher taxes. As Yglesias put it, “There is no doubt that this is a lot of money. It amounts to approximately 16.7 percent of GDP, which would obviously be a huge increase in the size of the federal budget,” but, nonetheless, the rich can “afford to pay higher rates.”

Rebuttals like Yglesias’s amount to a defense of giving the rich a lump sum tax cut in exchange for an offsetting marginal tax hike, reducing work effort to no real end. Ignored is the alternative where we don’t transfer thousands of dollars to middle and upper income people in the first place. Remember, much of that 16.7 percent of GDP would be government taking income from the wealthy and giving it straight back. And as the famous economist Arthur Okun once pointed out, when the government transfers money, it does so in a leaky bucket.

What About Loss Aversion?

When I made this point to Scott Santens, arguably UBI’s leading advocate, he countered that phasing-out UBI directly through means testing, versus phasing-out UBI indirectly through higher tax rates, while analytically identical as far as disposable income is concerned, have different behavioral implications.

@hamandcheese @MacRoweNick Clawbacks and paying taxes are psychologically different in perception. See this study: https://t.co/gwsmCYGcGO

— Scott Santens (@scottsantens) April 20, 2016

This argument, while interesting, is grasping at straws. People have loss aversion, certainly, but that’s not an argument against phasing-out a Basic Income. Rather, it’s an argument for being careful about how the phase-out is framed and communicated. Getting a refund on your tax return feels pretty good as is, despite the existence of possible worlds where the refund could have been larger.

On the topic of behavioral implications, policy makers cringe whenever they hear the massive trillion dollar gross cost of a UBI, so why not quote the (substantially smaller) net cost embodied in an NIT? One can even continue marketing it as “Basic Income” since it still works to provide an income floor for one and all.

The Cost Difference Between UBI and NIT is Significant

Just how much of a cost difference is there between a UBI and NIT? To get a rough idea, I used the Census population survey’s Annual Social and Economic Supplement, which has the distribution of individuals over the age of 15 by income level in $2,500 intervals (I subtracted retirees). I then calculated the transfer each quantile would receive based on a hypothetical NIT which starts at $5,000 for individuals with zero income and is phased out at a rate of 30%. Multiplying the average transfer by the number of actual individuals in each grouping and summing, I arrived at total cost of $182 billion—roughly the combined budget for SSI, SNAP and EITC.

Recall that the naive way of calculating a $5,000 UBI would be to simply multiply $5,000 by 320 million people to arrive at total cost of $1.6 trillion. Yet by framing the Basic Income as an NIT, not only is it conceptually clearer, but the back-of-the-envelope price tag drops an order of magnitude.

That’s significant. If a Basic Income is ever going to have a life outside the minds of policy wonks, allaying fears of its budgetary impact is a big and necessary first step.