Last night, President Donald Trump announced, via tweet, a new tariff policy targeting Mexico. The tariff, which is set at 5 percent, “will gradually increase until the Illegal Immigration problem is remedied,” according to the Thursday afternoon tweet. The purpose of the tariff is to pressure Mexico into ramping up its border security measures, but it will ultimately be up to the White House to determine when Mexico has “remedied the problem,” which leaves many wondering how long the tariff will last.

The new tariff is a misinformed and irrational response to an ongoing migration trend rooted in regional dynamics of violence that can’t be “remedied” simply by sealing off the U.S. and Mexican borders. A durable solution requires creativity; intentional cooperation with Mexico; recognizing the historical roots of violence in Central America; and acknowledging that applying for asylum is a human right enshrined in international law. The tariff policy is nothing more than a deviation away from the comprehensive solutions that will allow for long-lasting regional stability and the protection of the human rights of migrants.

Furthermore, Mexico’s approach to migration, especially in the context of the recent caravans, differs categorically from the United States’ approach to migration, and a stricter regulation of its southern border will prove to be exceedingly difficult and has the potential to put migrants in more danger.

While much of the media attention surrounding migrant caravans has been focused on their arrival and detention at the U.S.-Mexico border, relatively less attention was directed toward the ways Mexico received and integrated the caravan members along their journeys. Now that Mexico’s migration policy has been targeted by the Trump administration, it’s important to understand exactly how Mexico has responded to the migrant caravans. With a presidential transition in December, a chronically underfunded migration system, and a recently-implemented policy of austerity designed to cut government spending by over $6 billion, it would seem challenging for Mexico to construct an effective approach to the arrival of large numbers of migrants at its southern border.

But Mexico’s migration policy in the past few months reflects innovation and a prioritization of the human rights of migrants, despite institutional challenges surrounding its implementation. While there are valid criticisms of Mexico’s migration policy and a resilient culture of corruption within migration institutions that leads to severe human rights abuses, it’s worth highlighting what Mexico has achieved and exploring if its policies might be transferable to other countries.

Tear Gas and Open Arms?

Mexico’s former President — Enrique Peña Nieto — initially employed a security-based approach to the arrival of the first group of Central Americans at Mexico’s southern border in October, deploying hundreds of federal police and even firing tear gas at migrants attempting to cross. This move was met with condemnation from human rights groups and praise from President Trump, who lauded Peña Nieto for his attempts to keep the migrants from entering Mexican territory.

Shortly thereafter, Peña Nieto implemented the Estás en Tu Casa (You Are At Home) plan, which offered temporary work permits to migrants, but only if they agreed to stay in the southern states of Chiapas and Oaxaca.

Though this was criticized by migrant-rights groups as an attempt to keep migrants from continuing toward the northern border and force them to stay in a region of Mexico with relatively high unemployment, it’s arguably more comprehensive than U.S. policy, which bars migrants from getting work permits for at least 180 days or until their asylum case is favorably resolved.

On December 1, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, a center-left former mayor of Mexico City, became president and ushered in a new migration policy. Focused on protecting the human rights of migrants in Mexican territory, López Obrador launched a humanitarian visa program that differed significantly from Peña Nieto’s approach.

The humanitarian visa allows for free movement within Mexico, as well as work authorization for up to one year, with possible renewal. Upon the arrival of another caravan in January, the Mexican government symbolically opened its borders, migrants were amicably greeted by migration officials, and the National Institute of Migration began expeditiously issuing humanitarian visas to all migrants. After the January caravan arrival, the Interior Secretary of Mexico — Olga Sánchez Cordero — announced that the issuing of humanitarian visas would be limited. However, Cordero extended Border Worker Permits and Border Visitor Permits — which previously were only available to Guatemalans and Belizeans — to Salvadorans and Hondurans.

As part of its Central America and Mexican Development plan released on May 20, the López Obrador administration proposed a human security approach rather than a national security approach to migration, and promised jobs to migrants in Mexico’s southern region, where López Obrador plans to launch a series of infrastructure projects. The Border Worker Permits and Border Visitor Permits will allow Guatemalans, Belizeans, Hondurans, and Salvadorans to work on the infrastructure projects, presumably as they wait for violence in their home countries to subside.

Applications for Refugee Status

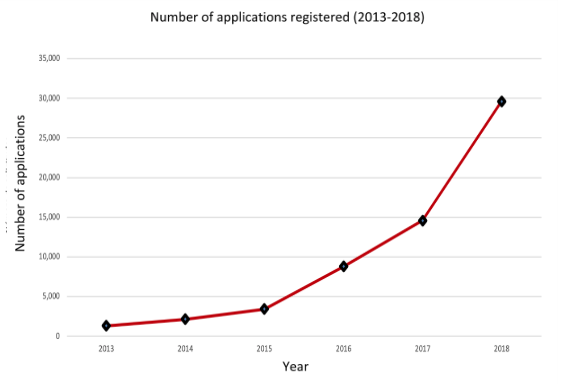

Mexico recently appealed to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) for financial assistance with its plans to open three more refugee processing centers, in Monterrey and Tijuana in the north and Palenque in the south, in an attempt to ease the burden at other processing centers. According to COMAR, the Mexican Commission for Assistance to Refugees, the number of applications for refugee and asylum status in Mexico filed over the past five years has increased drastically, nearly 2,000 percent since 2013. With 2019 refugee status requests expected to double 2018’s, and a backlog of up to two years, Mexico’s refugee system is preparing for a surge that many argue it can’t handle, especially considering that COMAR — the agency in Mexico that manages applications for refugee status — had its budget cut for 2019.

Still, unlike in the United States, under López Obrador’s new policy applicants for refugee status are able to apply for a temporary visa that allows them to work, access social services, and enroll in public schools. The temporary visa expires after one year but can be renewed if the application for refugee status has not yet been resolved. Additionally, applicants for refugee status receive assistance from the UNHCR and from local UNHCR-affiliated nonprofits.

One downside is that applicants for refugee status must sign in every other week at the COMAR branch where they filed their application, which limits their mobility within Mexico. Only in rare cases can applications be transferred, usually if applicants face violence or persecution in the state where they filed their application.

Also worth mentioning is the expansiveness of Mexico’s refugee law. Unlike in the United States, Mexico’s refugee law recognizes the multiple forms of violence that may cause a migrant to feel that they are not able to return to their home country; in accordance with the Cartagena Declaration of 1984, which Mexico but not the United States has signed, the law cites generalized violence, internal conflict, and massive violations of human rights as grounds for seeking asylum or refugee status. These provisions are much more aligned with contemporary dynamics, especially in Central America, where nonstate actors terrorize citizens in unprecedented ways.

Criticisms

Though Mexico’s migration policy appears to be more progressive on paper than the United States’ policy, and the rhetoric coming from Mexican officials has been markedly more amenable to migration than in the United States, there are still some serious criticisms of Mexico’s migration policy that merit attention. For one, recent reporting by Vice revealed a number of cases in which migrants were extorted by migration officials, some of whom were affiliated with local gangs. Violence against migrants remains common in Mexico and is generally not covered by the media to the extent that recent migrant deaths in U.S. detention centers have been covered, rendering invisible grave violations of human rights. Those who travel on the Bestia — the widely used system of stowing away on cargo trains to reach the U.S. border — face high risk of death or severe injury; many have had limbs amputated after having fallen off.

Violence against migrants passing through Mexico or who planning to stay in Mexico disproportionately affects vulnerable subgroups, with many documented cases of human trafficking and forced prostitution of young girls; sexual assault; kidnappings; and severe discrimination against LGBTQ-identifying migrants. A general lack of accountability, climate of corruption, and underfunded migration system have allowed for an illicit market of migration exploitation to fester throughout the country, resulting in the recruitment of migrants into local gangs and a “mercantilization” of migrant bodies through extended networks of human trafficking, robbery, and kidnapping. Mexico’s inability or unwillingness to address violence against migrants and invest more heavily in its migration institutions ultimately puts migrants in situations of precariousness and undermines its wide-reaching and amply-developed migration laws.

What We Can Learn From Mexico

Though migrants passing through or staying in Mexico are often exposed to high levels of violence and precariousness, there are a number of policies that Mexico has implemented that are innovative and might be worth considering in the United States.

For one, immediate work authorization for asylum applicants would reduce the burden on detention centers and provide applicants with a sense of autonomy; if their application is approved, prior work experience would make their integration process much easier.

Second, like in Mexico, the United States is planning large-scale infrastructure programs, and including immigrants in these projects with temporary work permits could create a mutually reinforcing relationship that benefits the projects and provides immigrants with a stable income, some of which could be sent back to home countries in the form of remittances and help alleviate country-of-origin poverty. Third, Mexico’s human security versus national security approach, though worth interrogating when considering the violence experienced by migrants in Mexico, offers a useful, humanitarian framework that views migrants not as threats but as equally deserving of human rights and security.

Lastly, but not exhaustively, the United States should consider updating its refugee policy in accordance with contemporary dynamics of violence. The 1980 Refugee Act, which was passed unanimously by the U.S. Senate in 1979 and signed into law in 1980, was constructed in the context of the aftermath of the Vietnam War, taking into account what were then new dynamics of migration. But, the times have changed. While Mexico has updated its laws in a way that’s appropriate for the 21st century, the United States still relies on decades-old definitions of “refugee,” and even these definitions have been limited by the Trump administration.

A long-lasting solution to migration in the Americas requires creativity and a willingness to think beyond borders, and a hastily devised tariff policy will distract from real solutions. Though Mexico still has a lot of work to do when it comes to protecting migrants, its laws and recent approaches offer interesting insight into a migration policy that’s appropriate for the 21st century, and the United States would do well to consider borrowing from Mexico’s playbook instead of coercing Mexico into adopting hardline policies that are ineffective and put migrants in unnecessary danger.

Photo Credit: Gage Skidmore via Wikimedia Commons