Tax reform season is on us again. The recipe for effective tax reform, as all good economists know, is first to simplify and close loopholes, and then adjust marginal rates to meet revenue targets. Following that recipe, repealing the home mortgage interest deduction should be priority No. 1. for policymakers. The mortgage deduction is unfair, bad economics, and it serves no socially useful purpose.

The home mortgage interest deduction is unfair

It’s no surprise that the mortgage interest deduction has an extreme tilt toward the rich. What? Are you the last person alive who thinks the deductibility of home mortgage interest is a tax break for the middle class? Think again.

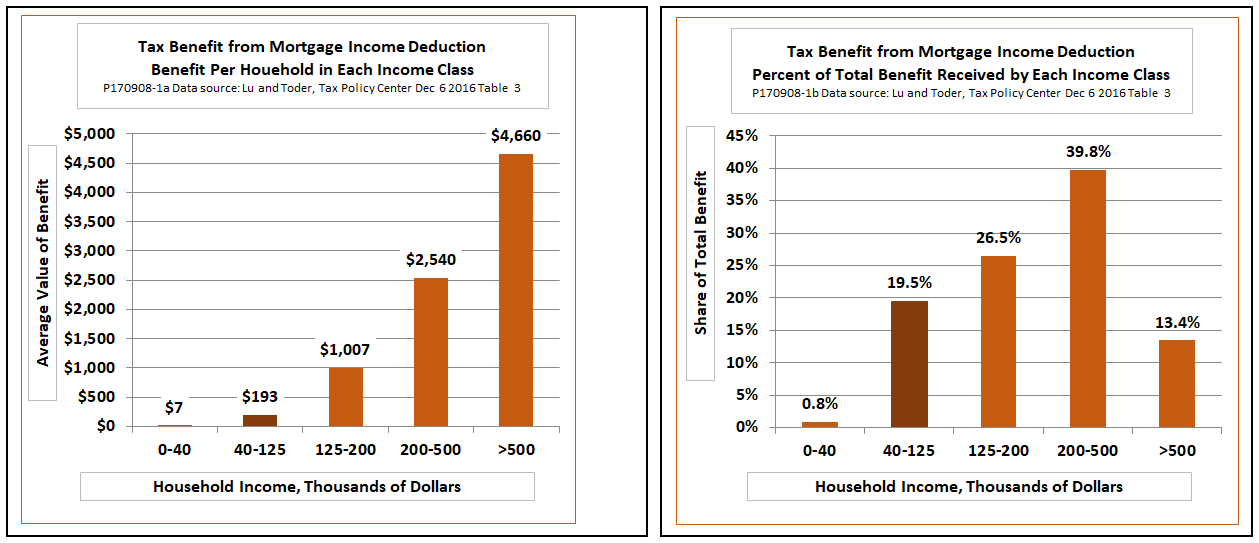

The following chart, based on data from a 2016 study by Chenxi Lu and Eric Toder of the Tax Policy Center of the Urban Institute and Brookings Institution clearly shows who wins and loses. The chart highlights the effects on middle-class households ranging from 67 to 200 percent of median household income, or about $40,000 to $125,000 per year. Just under half of all U.S. households fall in that income bracket, but, as the left-hand panel of the chart notes, they receive less than a fifth of the total tax benefits from the mortgage interest deduction. Higher-income households receive 80 percent of the total benefits. Lower-income households get almost nothing.

In part, middle-class households get little from the mortgage deduction because only 21 percent of homeowners claim it all, and on homes with much smaller mortgages than what wealthy households can afford. The rest either do not own a home, do not have a mortgage, or have a tax bill that is lower if they use the standard deduction instead of itemizing.

As the right-hand panel of the chart shows, the bias in favor of the wealthy is even greater when stated in terms of the dollar value of benefits per household. Middle-class households get an average benefit of $193 a year, while those with higher incomes get five, 10, or even 20 times as much.

Ironically, though, upper-income homeowners are not the main lobbying force favoring retention of the mortgage interest deduction. That role goes to a loose coalition of real estate agents, mortgage brokers, and bankers who earn a percentage of the sales price for every home transaction. They love the deduction because it pushes up the price of both new and existing homes. The deduction does that because it increases the maximum monthly payment that a buyer can afford to carry for any given income. More affordable mortgages, in turn, translate into more intensive bidding for the limited supply of housing in prime locations. Buyers who shy away from the high prices of prime properties are pushed farther out into the suburban sprawl, but that is another story.

The mortgage deduction is bad economics

Economists are concerned as much about the efficiency of the tax system as its fairness. An efficient tax code distorts an efficient market’s allocation of resources as little as possible. In the present case, that would mean a tax system that kept the playing field as level as possible between investments in housing and other sorts of assets, and between renting and home ownership. The mortgage interest deduction flunks the level playing field test in both respects.

Suppose you are the owner of an apartment building. Like any other business, you pay tax on income you earn and deduct interest you pay on the loan you took out to build or buy your property. In contrast, if you are an owner occupant, you deduct your interest expense but you do not pay income tax on the rental value of your property. That gives owner-occupants an edge over renters.

In principle, there are two ways to level the playing field between renters and owners. In theory, the best way would be to tax owner-occupants on the imputed rental value of their homes (say, $20,000 per year for a modest middle-class home) and then allow them to deduct mortgage interest expense. However, countries such as the United Kingdom and Sweden that have experimented with that system have found it administratively impractical. The next-best way to level the playing field is neither to tax imputed rental income nor to allow interest deductions. Canada, Australia, France, Germany follow that route.

The U.S. system, which does not tax imputed rents but does allow deduction of interest expense, has negative implications for the macroeconomy as well. An OECD report on housing policy estimates that the after-tax interest cost of housing finance in the United States is more than a full percentage point below market financing costs for other types of investments. The report notes:

Tax favoring of housing can lead to excessive housing investment and crowd out more productive investments, thereby adversely affecting productivity and growth. Moreover, taxes which favor home ownership may encourage speculative behavior by lowering the cost of borrowing to finance housing investment. In turn, this can raise house price volatility with adverse consequences for macroeconomic stability.

The OECD report also notes that, although the tax treatment of mortgage interest was not the only cause of the housing bubble that preceded the global financial crisis of 2008, it was one of the contributing factors.

Mortgage interest deduction serves no useful social purpose

The idea of home ownership as a personal and civic virtue is deeply engrained in the American consciousness. A report from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, The National Home Ownership Strategy, maintains that home ownership is conducive to personal financial security, stable families, good citizenship, and stronger communities — all points echoed by special interest groups in their defense of the mortgage interest deduction.

Yet this simply takes for granted that the mortgage interest deduction actually increases home ownership, when the empirical evidence simply isn’t there. Indeed, a landmark new study of what happened when Denmark reformed its own mortgage interest deduction finds that “the mortgage deduction has a precisely estimated zero effect on homeownership,” both in the short and long run. Instead, the authors find that mortgage interest deductibility merely induces home buyers to buy bigger and more expensive homes. In other words, the deduction doesn’t subsidize home ownership so much as it subsidizes conspicuous consumption.

But what of the vaunted positive externalities to owning a home? There is some evidence (cited here) that homeowners may actually be less neighborly and less active in their communities than renters. But even where there does appear to be a positive correlation between home ownership and good citizenship, we should be cautious in attributing causation. For example, better education might be a causal factor for better citizenship, and also for higher personal income and greater likelihood of home ownership.

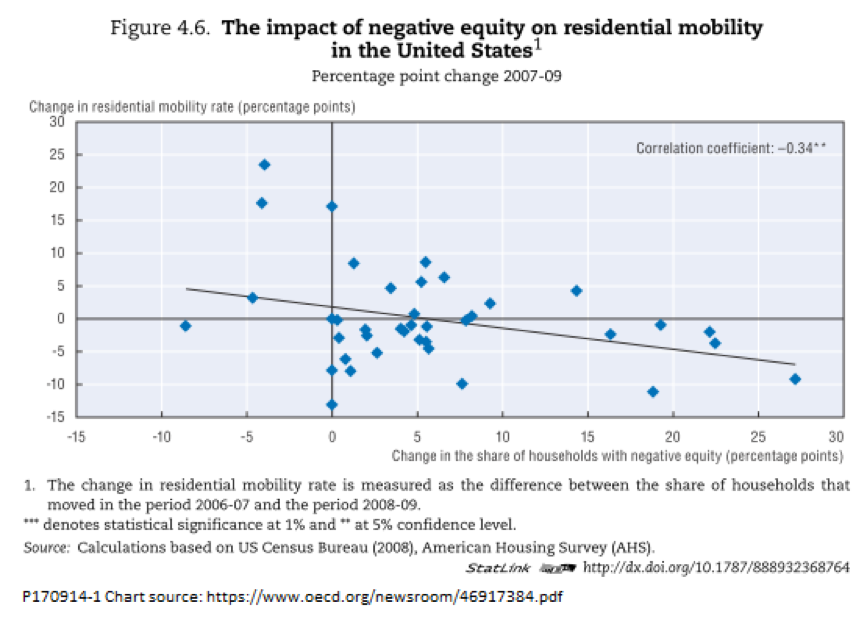

Reduced geographic mobility is another potential negative effect of greater home ownership. Research by David Autor and colleagues has shown that adverse shocks from trade and technology tend to be geographically concentrated. When such a shock hits, it depresses local housing prices. Displaced workers find themselves with homes that are worth less than the outstanding balances on their mortgages. It becomes nearly impossible for them to sell and move elsewhere to find new jobs. The OECD report cited earlier includes this chart, which shows a negative relationship between trends in mobility and an increasing share of U.S. home owners with negative equity:

True, mortgage-financed home ownership is not the only factor that has undermined labor mobility in the U.S. economy. The expansion of occupational licensing, the state-by-state balkanization of the health care system, increasing numbers of ex-offenders in the labor force, and other factors have all played a role. But, since renters tend to be more mobile than homeowners, government policies favoring home ownership remain an important contributing factor.

How to repeal the mortgage interest deduction

It would be tempting to just say “No” to the mortgage deduction and abolish it outright, but its distortions are so baked into the economy that immediate repeal could cause problems. The biggest problem is that the deduction has been capitalized into existing home prices. If it were removed suddenly, current homeowners would face a double hit: Higher after-tax cost of making payments on their mortgages plus a sharp drop in the resale value of their homes.

To ease the pain of transition, it would be wise to grandfather in the deductibility of existing mortgages. To prevent a sudden crash in prices, the deduction on resale of existing homes could be phased out gradually. For example, the cap on the maximum size of a mortgage to which the deduction applies, now $1 million, could be lowered year by year until it fell to zero. This already is occurring thanks to inflation, but the process could be greatly sped up. Meanwhile, deductibility could be ended immediately for mortgages on newly built homes.

Repeal of the mortgage interest deduction should be a no-brainer for tax reformers. Progressives who think that the rich are not paying their fair share of taxes should be among the first to support the “No” campaign. Conservative foes of government meddling in markets should join them enthusiastically. Economists worried about efficient resource allocation and macroeconomic stability should add their voices, too. If ever there were an aspect of tax reform that should command bipartisan consensus, the repeal of the mortgage interest deduction is it.

Follow-up: October 17, 2017. GOP tax reform plans propose keeping the mortgage deduction but doubling the standard deduction. The net result, as explained in this note, would be to increase the degree to which benefits of the mortgage deduction are skewed toward high-income households. Within the middle class, there would be both winners and losers.