Robert Bork began his influential 1978 book, The Antitrust Paradox, with the story of a prominent attorney (and future Supreme Court justice) at an American Bar Association meeting of several hundred antitrust lawyers, arguing that a good antitrust regulator behaves like “the sheriff of a frontier town: he did not sift the evidence, distinguish between suspects, and solve crimes, but merely walked the main street and every so often pistol-whipped a few people.”

Tim Wu, a law professor at Columbia University, argues in his new book, The Curse of Bigness, that American antitrust enforcement should return to that bygone era. Among other policy proposals, Wu recommends a “simple but per se ban on mergers that reduce the number of major firms to less than four.” He also proposes that regulators use breakups rather than consent decrees because they are “self-executing” and “a much cleaner way of dealing with competition problems.”

In his narrative history of American antitrust law, Wu’s hero is Louis Brandeis, who served on the Supreme Court from 1916 to 1939 and coined the phrase “curse of bigness” to refer to the societal problems he saw as engendered by Gilded Age monopolies. Bork is the villain of the story, having spearheaded the Chicago School’s role in narrowing antitrust regulation to economic concerns and establishing consumer welfare as its lodestar.

The Small Business Myth

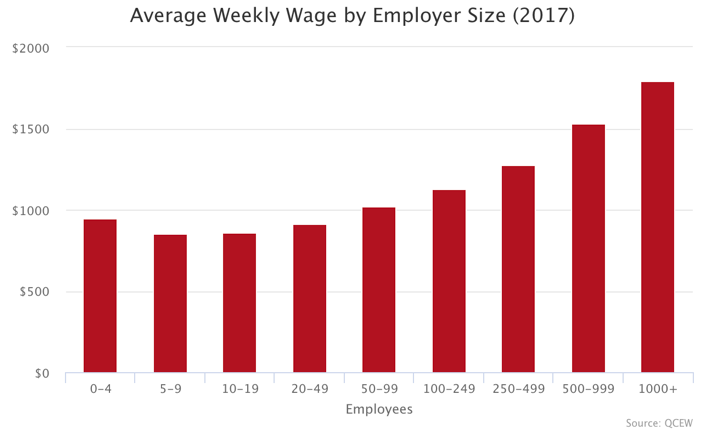

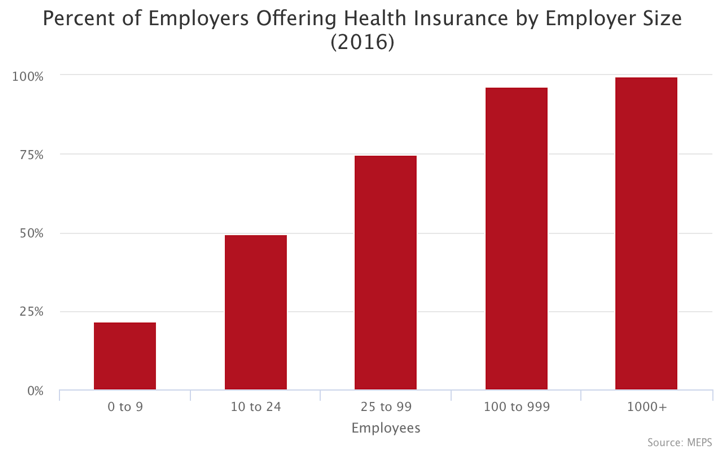

While it is understandable that Brandeis suspected there was a curse of bigness in the economy given the paucity of data available at the time, the same cannot be said in Wu’s case. In their book published earlier this year, Big Is Beautiful, Robert D. Atkinson and Michael Lind show that large firms pay their employees more than small firms, give their employees better benefits, create more jobs on a net basis, and employ a more diverse workforce. Big business is more likely to be unionized than small business, and workers in large firms are less likely to be laid off or injured on the job. Large companies are also an engine of productivity growth, investing more in both research and development and in employee training.

Source: Jacobin

Source: Jacobin

Citing much of the same evidence, socialist writer Matt Bruenig has tried to persuade the left that small businesses are overrated, noting that “In reality, small-business promotion is mostly a bad idea. Small businesses pay lower wages, provide worse benefits, are often exempt from important worker protections, and are incompatible with the way unionization works in the U.S.” Rejecting the myth of small business is thus neither a left- nor a right-wing conspiracy, as in Wu’s cynical narrative of the Chicago School. Rather, recognizing the value of bigness is possible whether your primary concern is for the well-being of workers or economic productivity overall.

Conflating Natural Monopolies and De Jure Monopolies

But maybe bigness tips from a positive to a negative when a single firm takes over a whole market. Monopolization enables companies to raise prices and lower output for the sake of maximizing profits. However, if we are to vanquish the evils of monopoly, we must distinguish between its sources. Natural monopolies, which exist due to high fixed costs or economies of scale, differ from government-granted monopolies, and the two require distinct policy responses. Here again, Wu’s analysis falls short.

In the most infamous case of abusing market power in recent memory, Martin Shkreli, now in prison for securities fraud, raised the price of an infectious-disease drug from $13.50 to $750 overnight. In his retelling, Wu fails to mention that Shkreli was only able to profitably jack up the price of this lifesaving drug because of a regulatory backlog at the FDA. Daraprim, the drug in question, was no longer under patent, but no other producer was approved to sell the generic, and the approval process is notoriously long in the United States.

Similarly, whenever discussing Big Pharma or hospital monopolies, Wu erroneously characterizes them as the consequence of derelict antitrust regulators lacking sufficient will to enforce the laws on the books. Yet in many of these cases, the lack of competition is a result of poorly-designed patent laws and exclusionary regulations, from certificate-of-need laws to occupational licensing. As my colleague Will Wilkinson put it, “There are companies that do nothing but hoard pre-existing tech patents and then sue everyone who comes within a country mile of infringing on one of them … Just buy up little state-sanctioned monopolies, then make a mint destroying rather than creating economic value.” This is monopoly at its worst, yet Wu’s framework provides little help in understanding it.

The inability to distinguish between natural and government-granted monopoly is most glaring when Wu says the “original Boston Tea Party was, after all, really an anti-monopoly protest.” Yes, but it was a protest against government-granted monopoly. The British government had passed the Tea Act of 1773 to reinforce the East India Company’s monopoly on the sale of tea in the colonies. If private power had been the real concern of the protest, maybe the colonists would have revolted against the East India Company instead of King George III.

Simple Industry Concentration Ratios Can Be Misleading

“In a run that lasted some two decades, American industry reached levels of industry concentration arguably unseen since the original Trust era. A full 75 percent of industries witnessed increased concentration from the years 1997 to 2012,” Wu explains. He goes on to use increasing market shares by companies ranging from AT&T to Bayer to Ticketmaster to sound the antitrust alarm.

But market share statistics, which are used to define a monopoly in structural analysis, often obscure more than they reveal about the state of competition in an industry. To deal with this problem, antitrust economists have developed more advanced analytical tools for studying market power, such as diversion ratios, the Gross Upward Pricing Pressure Index (GUPPI) test, and merger simulations. A deeper look at the beer, airline, and book retailing sectors shows how relying solely on the structural framework leaves much to be desired.

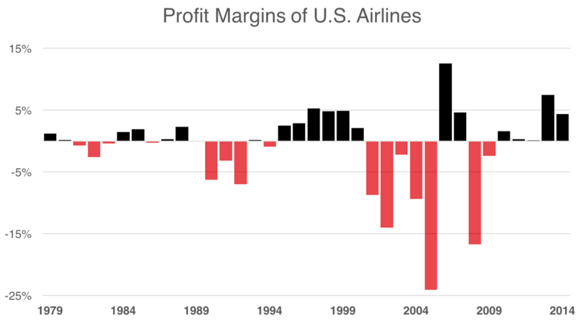

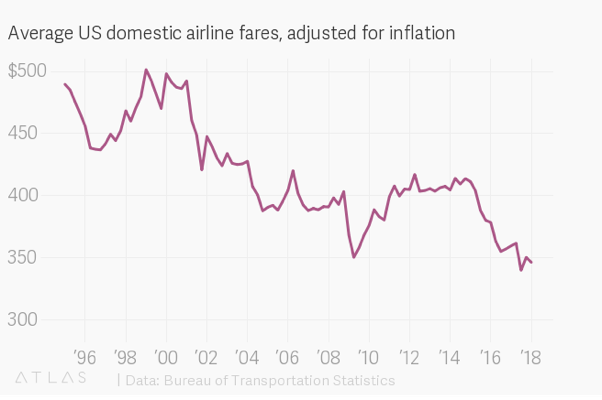

Mergers in the airline industry have left us with only three traditional major airlines. That must lead to monopoly profits, right? In fact, as the Priceonomics blog notes, “six major airlines went through bankruptcy in the 2000s, and from 1979 to 2014, airlines lost $35 billion.” One recent paper in the American Economic Review was simply titled “Why Can’t US Airlines Make Money?” Airfares are also down by about a third over the same period. It is hard to conclude that allowing mergers in a persistently unprofitable industry with falling prices and rising output is really what ails our society.

Source: Priceonomics

Source: Quartz

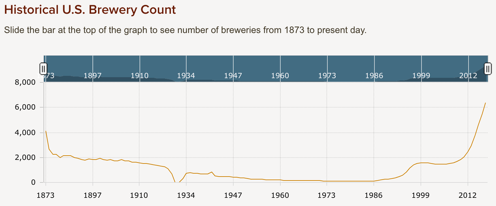

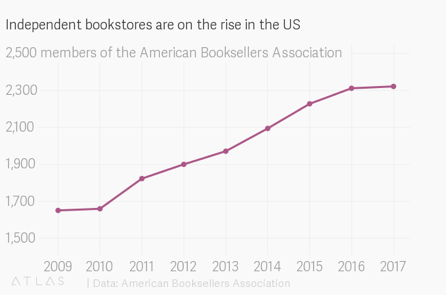

The book also notes ominously that after recent mergers and acquisitions in the beer industry, “Anheuser-Busch InBev and MillerCoors control over 70 percent of beer sales.” But there are more than 6,000 breweries in the United States, a 150-year high. Is this really a market that lacks choice or is difficult to enter? Of all of its markets, Amazon is most dominant in books, which is no surprise considering it was the product category that launched the company. So did Amazon kill the independent bookstore? Not quite. The number of indie bookstores is up by about 35 percent in the last decade.

Source: Brewers Association

Source: Quartz

The trickiest part of market definition in antitrust analysis is determining the boundaries of the market. Which products are inside or outside of the market? In modern antitrust analysis, this question is important but not essential, as there are many other factors for determining competitive effects. In the old, structural approach, which relies on bright-line presumptions based on market shares, market definition is pivotal. Consider Amazon, which has 49 percent of the U.S. e-commerce market but only 5 percent of the U.S. retail market. Which one is the appropriate market for structural analysis? Or take Google and Facebook. In the U.S., together they control 57 percent of the digital advertising market but only 25 percent of the total advertising market. Which one is the appropriate market for structural analysis?

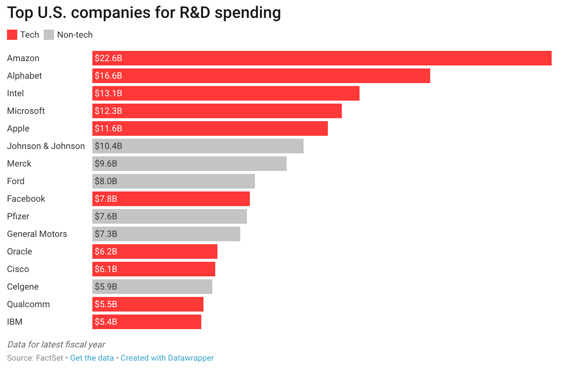

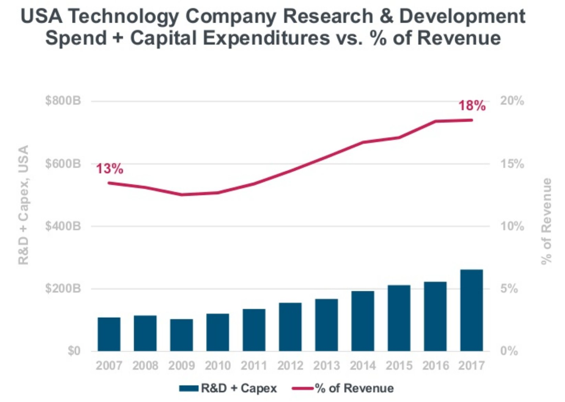

The second-to-last chapter of Wu’s book is titled “The Rise of the Tech Trusts,” and the extra attention these companies receive is understandable given their prominence in the economy. But before we break up Big Tech, there are other important facts about the tech industry to consider. The top five companies that spent the most on research and development last year were all tech companies. Combined spending on R&D and capital expenditures at technology companies is increasing as a percent of revenue over time. The Big Five — Apple, Amazon, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft — may be dominant, but they also compete against each other in a wide range of product categories. Big tech companies simply are not acting like the complacent monopolies Wu portrays.

Source: Recode

Source: KPCB

Most importantly, policymakers should be cognizant of the cyclical nature of the tech industry. AT&T was dominant in telephone service; IBM in mainframe computing; Microsoft in desktop; AOL and Yahoo in Web 1.0; Google and Facebook in mobile. As Benedict Evans shows, each cycle in tech allows a few dominant companies to build a moat and create quasi-monopolies. No competitor ever does cross the moat — the castle just becomes irrelevant when the next cycle begins.

Economics Is Not a Morality Play

Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman once wrote: “Economics is not a morality play. It’s not a happy story in which virtue is rewarded and vice punished. The market economy is a system for organizing activity … with no special moral significance. The rich don’t necessarily deserve their wealth, and the poor certainly don’t deserve their poverty.”

In the early chapters, Wu makes a strained connection between the Social Darwinists and the Gilded Age monopolists, claiming they were motivated by the same eugenicist ideology as applied to society and business. The problem with inferring moral motives behind economic decisions is that they don’t neatly map onto the good and bad teams. Teddy Roosevelt, the trustbuster himself, was also a eugenicist, an inconvenient fact left out by Wu.

In a letter to Charles Davenport, one of the leaders of the American eugenics movement, Roosevelt wrote that “society has no business to permit degenerates to reproduce their kind … Any group of farmers who permitted their best stock not to breed, and let all the increase come from the worst stock, would be treated as fit inmates for an asylum … we have no business to permit the perpetuation of citizens of the wrong type.”

Wu’s book does a serviceable job relating the history of American antitrust law, but one wonders whether we should follow antitrust policy recommendations from an author who makes claims about economic concentration leading to the rise of Nazism based on sources that don’t withstand the most basic scrutiny.

Wu makes errors and omits facts when they serve his narrative, substituting rigor for a simple story of good versus evil. The book is particularly ungenerous in its description of Peter Thiel’s short essay, “Competition Is for Losers,” which argues that entrepreneurs should pursue businesses or product lines that are hard to substitute — a call for startup founders to resist being copycats that gets translated by Wu, through omitted context, into a kind of “monopoly worship.”

In sum, Professor Wu fetishizes “smallness” despite the evidence showing that most things progressives and free-marketers alike value increase with firm size. He conflates natural and de jure monopolies, underrating the role that regulations and patent law play in establishing and sustaining monopoly power. He advocates returning to a structural approach in antitrust enforcement despite it being abandoned by empirical researchers decades ago because “market structure and competitive effects are not systematically correlated” except in special circumstances. And lastly, in an attempt at narrative, Wu constructs a morality play in which he lobs ad hominem attacks at monopolists for their ethical shortcomings and abhorrent political viewpoints, when many of the same viewpoints were held by the trustbusters he otherwise praises.

It is easy to demonize and scapegoat big business, particularly tech companies. At a time when the president of the United States views many of those same companies as his political enemies — and is groping around for any tool to punish them — it is disappointing that one of our leading policy thinkers wants to hand him the biggest club of all.