President Trump has presided over the systematic dismantling of the American refugee resettlement system as we know it. Record low refugee caps, the travel ban, and “extreme vetting” have captured the public’s attention, but the administration has also quietly derailed the refugee program in a myriad of other ways that have long-term implications. The U.S. is on pace for record low refugee admissions in 2018 while the total number of refugees around the world is at a record high.

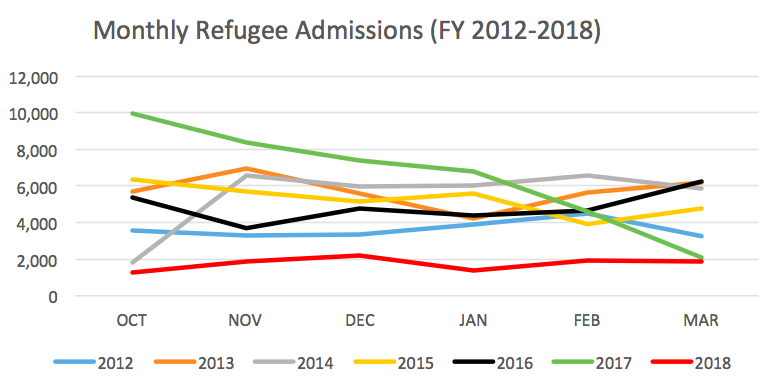

So far in FY 2018—from October to the end of March—the U.S. has resettled 10,548 refugees, a total woefully short of this year’s cap of 45,000. Not only is the cap the lowest since Congress created the modern refugee program in 1980, but even the share of the cap admitted through March is half of the average share in the same period over the last five years.

President Trump wasted little time after his inauguration before signing the now-infamous executive order that blocked all immigrants from “terror-prone” countries for 90 days and suspended the refugee program for 120 days. The suspension gave time for officials to develop new, “extreme” vetting procedures. It also resulted in the expiration of medical and security checks for refugees already in the pipeline.

Those who already been cleared would have to be screened once again, slowing down the resettlement process by months. Noah Gottschalk of Oxfam argues these expirations “reset the clock”, forcing many refugees back to square one of the screening process. That was a main reason why fiscal year 2017 saw the lowest refugee admissions total in a decade. And this year will be even worse.

When the administration resumed resettlement from “high-risk” nations, they added enhanced screening measures on top of what was already a two-year vetting process. So even though the ban has been lifted, the effects persist: an effective choke on refugees from certain countries.

Consequently, only 44 Syrian refugees were resettled through the end of March according to State Department data. Last year that number was 5,839 for the same time period. For Iranians, 1,969 were resettled by the end of March last year and 31 have been resettled this year. For Iraq, more than 5,676 last year and 106 this year. For Somalia, 4,917 last year and 201 this year.

Although these nations have received the brunt of the reductions, the overall monthly refugee admissions—as detailed in the chart above—are the lowest they have been since 2012 and it’s not close.

Bob Carey, a former director of the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), told Politico the refugee program, “isn’t being managed—or, it’s being managed to fail.” He continued, “What couldn’t be achieved through executive orders is being achieved through administrative roadblocks or lack of will.”

The prospects for increased resettlement as the year proceeds are dim. Politico reports that DHS in the first quarter of this fiscal year has conducted less than one-third of possible “circuit rides,” in which Department of Homeland Security (DHS) officials travel to different countries and conduct refugee interviews. Moreover, the “rides” were shorter, staffed with fewer individuals, and included none in the Middle East. All of this diminishes capacity, grows backlogs, and siphons resources away from potential refugees fleeing persecution from Middle Eastern nations.

Refugee resettlement is overseen by nine resettlement agencies that work with 300 affiliate organizations to welcome newcomers stateside. Internationally, a robust network of NGOs nominate candidates for refugee status and provide aid. Without the domestic and global infrastructure built up over decades to identify, process, and serve refugees, bottlenecks worsen and the system grinds to a halt.

Last year, Voice of America reported closures of nonprofit offices serving refugees triggered at least 300 layoffs in the U.S. It’s worse overseas, where more than 500 staffers at headquarters, local offices, and affiliate organizations were let go.

The closures and layoffs have continued in 2018. The New York Times reported that Church World Service, one of the nine refugee resettlement agencies, laid off nearly their entire staff operating in Africa. One agency, World Relief, closed its offices in Columbus, Ohio; Boise, Idaho; Baltimore; Miami; and Nashville. Last month, the State Department closed dozens of refugee resettlement offices across the country that each process under 100 refugees annually.

Closing an office or firing support staff has consequences for years to come, as shutting down an office is dramatically easier than getting one back up.

Making matters worse still, closing offices and slashing budgets could create a vicious cycle that leads to future cuts. For example, as resettlement locations are drawn down, refugees could be matched to areas that may not be best for their integration or self-sufficiency. Or, as offices close and services are consolidated, support services and assistance may be sacrificed to the detriment of refugees’ abilities to find jobs and healthcare, learn English, and get a footing in their community. Refugee critics can then point to worse outcomes or higher costs to justify further cuts.

The administration sought to make a fiscal case in favor of restricting refugee resettlement. As my colleague Jeremy L. Neufeld commented on last year, administration officials intervened and blocked a Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) report that found refugees brought in $63 million more in government revenues than they cost over the past decade. These officials only wanted the costs of refugee resettlement to be evaluated, and for any fiscal benefit to be left out.

The administration intended a particular outcome for this study and when the facts revealed themselves—that refugees are a net benefit to the American economy—they resorted to suspect calculations and then suppressed the findings.

The year’s problems aren’t limited to our own refugee program.. Last December, the administration pulled the U.S. out of negotiations on the United Nations Global Compact on Migration. The proposed agreement would improve the way the international community responds to large-scale movements of immigrants and refugees. The administration argued involvement would infringe on American sovereignty.

In fact, the U.S. has been leading humanitarian efforts and recruiting partners to protect vulnerable populations for decades. The move, while not surprising, is symptomatic of the administration’s withdrawal of American leadership from the world stage.

These instances and others showcase an administration hellbent on restricting the refugee program. The administration is effectively dismantling the ability for the U.S. to resettle refugees not just now but also in the future. If the next administration wants to return the refugee program to normalcy, it will require large investments in building back up to capacity, effectively raising the costs of future resettlement. The Trump administration’s policies will reverberate in the refugee program even years after Trump no longer holds office.

Thanks to Niskanen intern Randy Loayza for research assistance on this post.