Last month, Kevin McAleenan — then commissioner of Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and now acting secretary of the Department of Homeland Security — said the U.S. immigration system was at a “breaking point.” He recognized that U.S. authorities are starting to run out of space — literally — to house incoming migrants and asylum seekers in detention facilities. A possible solution is to reinstate the recently terminated Family Case Management Program (FCMP) to provide civil society-driven alternatives to immigrant detention.

Simply put, the United States cannot detain its way out of the current humanitarian situation on the southern border. With approximately 93,000 CBP apprehensions in March, there is no affordable or practical way to detain these individuals, many of whom are asylum seekers and their children.

Moreover, vulnerable asylum seekers should not be subject to the trauma that comes with detention — families with minor children, trafficking and torture survivors, pregnant women, and the mentally and physically disabled should automatically be exempt from detention. Adding more beds is not a workable or worthy solution. Finding alternatives to detention that are effective, affordable, and scalable should be the goal.

The Family Case Management Program (FCMP) is one of those alternatives to detention that should be restored and expanded. FCMP used case managers to ensure participants complied with their legal obligations as they moved through immigration proceedings. Check-ins with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), attendance at immigration court hearings, and compliance with removal orders were overseen by caseworkers to ensure participants could remain in their communities and with their families. The program achieved high levels of compliance over its two-year run before it was terminated by the Trump administration in 2017.

FCMP offered community-based resources and services tailored to family needs, including transportation and logistics assistance, education about rights and responsibilities, planning for safe repatriation when required, and more. The program was active in five metro areas: Baltimore/Washington; Los Angeles; New York City/Newark, NJ; Miami; and Chicago. In total, the program achieved 99 percent compliance for check-ins and 100 percent compliance for court hearings. Just 23 out of 954 participants — 2 percent — absconded.

Two issues stand in the way of FCMP expansion: the massive asylum backlog that drives up costs, and a lack of administrative support.

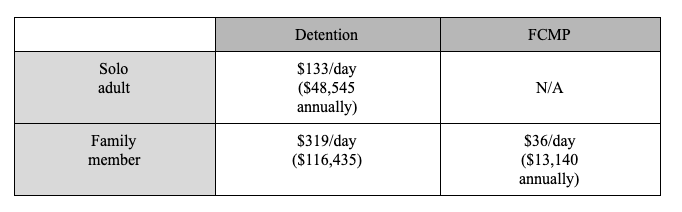

First, alternatives to detention such as the FCMP are significantly cheaper per day when compared to detention or family detention specifically. In 2016, the average per-day, per-person cost of FCMP was $36, according to DHS, compared to $133 per day for an adult in solo detention and $319 per day for an individual in family detention.

However, FCMP costs are heavily inflated when the massive asylum backlog is taken into account. An efficient immigration system would produce asylum decisions in a timely and predictable manner, but the asylum backlog and geographic disparities in processing have bogged down asylum decisions. Only one out of five asylum cases took 12 months or less to decide, according to data gathered by Syracuse University.

Second, ICE claims petitioners are sent back to their home country “at a much higher rate” in other alternative-to-detention programs as compared to FCMP, suggesting that the administration’s metric for program evaluation is not affordability, accuracy, or scalability, but rates of removal. The administration appears less interested in FCMP’s success in processing cases without resorting to detention and more interested in churning out negative asylum decisions. The right measurement for detention should not be removal, but compliance with prescribed judicial procedures and fair outcomes.

The United States is facing a crisis at the moment, but in many ways, it’s a political crisis of its own making. There is widespread misunderstanding of the motivations of Central American asylum seekers and the push factors at play in that region, fueled by lawmakers who are seemingly incapable of proposing tangible solutions.

Managing irregular migration from nearby countries is a difficult challenge for governments across the globe, but a Congress paralyzed by gridlock and partisanship and a White House advancing punitive and counterproductive proposals makes addressing this crisis next to impossible.

Nonetheless, FCMP and other solutions do exist and they deserve to be expanded. Relying on community partners in civil society has proven effective in ensuring compliance with immigration law — and that should be the focus in processing asylum seekers.

To be clear, reinstating FCMP is not a panacea for the current ills at the border or the exodus out of Central America, but family case management does serve a useful purpose for specific populations, and in conjunction with other programs and reforms will address the capacity issues at the border. Vulnerable asylum seekers deserve the opportunity to make their claim and wait beyond the confines of traumatic detention — family case management can give them just that.

Photo by Paddy O Sullivan from Pexels