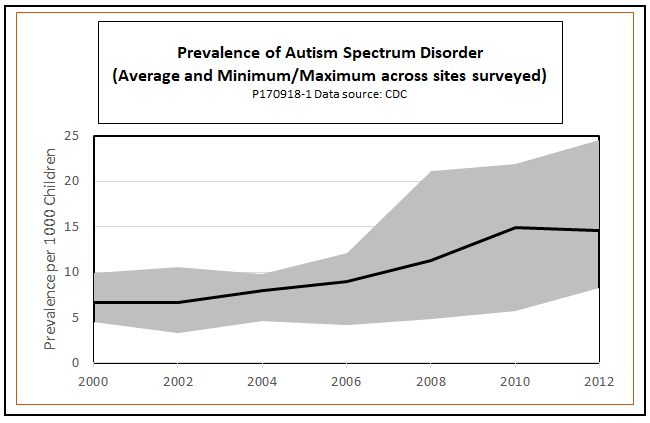

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has been tracking the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) since 2000. As the following chart shows, the identified prevalence of ASD among American children – especially boys – has been rising steadily. No one seems to know how much of the increase is due to greater prevalence of the disorder itself, or greater awareness and better diagnosis. It probably is a little of both. In any case, the number of people who were diagnosed with ASD in childhood and who now are entering adulthood is rising and will continue to increase.

Unfortunately, too many of those now entering adulthood with ASD are running into regulatory barriers that prevent them from getting the kind of care they need. This post explains the nature of those barriers and outlines changes that would help ensure appropriate care for all adults with ASD.

Origins: Deinstitutionalization

The widespread deinstitutionalization of people with mental illnesses has been one of the most dramatic changes in social policy in the United States since World War II. According to Dominic Sisti, Ph.D., an assistant professor of medical ethics and human policy at the University of Pennsylvania, the number of patients in state psychiatric facilities decreased from 560,000 in 1955 to just 45,000 in 2014, a 95 percent decrease in the per-capita institutionalization rate. (The linked article by Sisti and colleagues is behind a paywall, but a summary is available here.)

The deinstitutionalization movement was driven, in part, by new therapies that could be delivered outside an institutional setting and also by well-publicized abuse in mental institutions. There is no doubt that many people benefited, but for others, deinstitutionalization brought unintended consequences. For some, it resulted in “transinstitutionalization” to prisons, homeless shelters, and emergency rooms. For others, it has meant living on the street.

Needless to say, appropriate treatment is unavailable in most such situations, leading observers such as Sisti to argue for bringing back asylums. He uses the term in its original meaning as a place that is a safe sanctuary – facilities not simply for confinement but for the delivery of effective modern therapies. However, others, including Renée Binder, past president of the American Psychiatric Association, vehemently disagree – seeing care in settings that are closely integrated into communities as the only appropriate alternative.

The situation of people with ASD is somewhat different, because their transition typically begins not from an institution, but from their families. Still, as we will see, they, together with their parents and guardians, find the same challenges in finding an appropriate community or institutional setting for treatment. Understanding why will require a brief discursion into the law of mental health care.

The Olmstead decision and its divergent interpretations

In 1990, after the process of deinstitutionalization was well under way, Congress passed the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which recognized routine institutionalization as an impermissible form of discrimination. In 1995, two women tested the ADA, Lois Curtis and Elaine Wilson, who sued the state of Georgia for release from the state-run Georgia Regional Hospital. After the women were voluntarily admitted for a period to be treated for mental illness and developmental disabilities, mental health professionals had judged the women ready to move to a community-based program. However, they remained confined in the institution for several years.

The case eventually made it to the Supreme Court. In 1999, in Olmstead v. L.C., 527 U.S. 581, the Court ruled in favor the two women, holding that Title II of the ADA prohibits the unjustified segregation of individuals with disabilities. The court explained that “institutional placement of persons who can handle and benefit from community settings perpetuates unwarranted assumptions that persons so isolated are incapable or unworthy of participating in community life,” and that “confinement in an institution severely diminishes the everyday life activities of individuals, including family relations, social contacts, work options, economic independence, educational advancement, and cultural enrichment.”

That was all well and good as far as Curtis and Elaine were concerned, and Olmstead was liberating for thousands of others as well. From that date, institutional care would no longer be the one-size-fits all solution for the care of people with intellectual disabilities. In the years since, however, the federal government – acting through the Department of Justice (DOJ), the Administration on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), and the National Council on Disability – has interpreted Olmstead in a way that many think has turned the decision on its head.

More specifically, the controversy concerns the balance between treatment in settings that are fully integrated into the community and settings that are more asylum-like, in the benign sense of that term. DOJ, which places the headline “Community Integration for Everyone” on its page explaining Olmstead, explicitly refers to its policy as an integration mandate, not an integration option. The integration mandate is spelled out by the CMS in detailed regulatory language in Final Rule 2249-F and 2296-F, issued in 2014. The rules allow for a five-year transition period to full compliance, ending in 2019.

But the Supreme Court never intended to mandate community integration, as an analysis of the Olmstead case by VOR – a national advocacy group for people with ASD and other intellectual disabilities – makes clear. In particular, the decision specifies that institutional treatment is unjustified only when

[a] the State’s treatment professionals have determined that community placement is appropriate, [b] the transfer from institutional care to a less restrictive setting is not opposed by the affected individual, and [c] the placement can be reasonably accommodated, taking into account the resources available to the State and the needs of others with mental disabilities. (Olmstead, 527 U.S. at 587.)

The decision goes on to state:

We emphasize that nothing in the ADA or its implementing regulations condones termination of institutional settings for persons unable to handle or benefit from community settings. . . Nor is there any federal requirement that community-based treatment be imposed on patients who do not desire it. (Olmstead at 601-602).

Finally, it says:

Unjustified isolation, we hold, is properly regarded as discrimination based on disability. But we recognize, as well, the States’ need to maintain a range of facilities for the care and treatment of persons with diverse mental disabilities, and the States’ obligation to administer services with an even hand (Olmstead at 597).

In a concurring opinion, Justice Anthony Kennedy was even more explicit:

It would be unreasonable, it would be a tragic event, then, were the American with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA) to be interpreted so that States had some incentive, for fear of litigation, to drive those in need of medical care and treatment out of appropriate care and into settings with too little assistance and supervision. … In light of these concerns, if the principle of liability announced by the Court is not applied with caution and circumspection, States may be pressured into attempting compliance on the cheap, placing marginal patients into integrated settings devoid of the services and attention necessary for their condition.” (Olmstead at 610).

The trouble with ‘integration for everyone’

The trouble with “community integration for everyone” is that the autism spectrum – the “S” in ASD – is a very broad one. Some adults with ASD live normal lives in their communities with no ongoing supervision at all. Others thrive in the atmosphere of small group homes where four or five people live together, often working at suitable jobs, with the aid of one supporting staff member. But, there are more difficult cases. Here are some examples, taken from comments regarding the integration mandate submitted to the DOJ by VOR:

- A profoundly intellectually disabled young man in a wheelchair who has no concept of hazards cannot maneuver his wheelchair independently in the community, but can [do so] on his own in a large intermediate care facility (ICF) with long, wide hallways, no stairs to fall down, lots of areas to visit, and plenty of caregivers, visiting family members, and volunteers to keep a watchful eye on him. In a small community setting, this young man would find himself bumping into walls and furniture with his wheelchair.

- A severely autistic man prone to violent behaviors and elopement may be a danger to himself and others in a small setting. But he may find more freedom and independence in a large facility with more staff on hand to support his behaviors, more places to visit and activities to engage in, and in many cases, large grounds on which to take recreation where he cannot harm others.

- A severely intellectually disabled woman with quadriplegia and a ventilator likely will not have sufficient staff to take her on outings if she lives in a four-person group home with the typical 1:4 staffing ratio. She requires 1:1 supervision in the community and possibly nursing support.

- A severely autistic young lady with maladaptive behaviors may find a full work-day of supported employment daily in a sheltered workshop. She might be too costly to employ in a community business and her behaviors too hazardous to herself and others, which may severely limit the number of hours she is employable in the private sector.

The ICFs to which VOR’s comments refer are much larger and better-staffed than the community-based group homes favored by CMS regulations. Group homes typically house four or five residents in an ordinary residential home with one staff member on duty. ICFs are larger, campus-like facilities in urban or rural settings. Several such facilities are described in detail in this article from The Atlantic.

Unfortunately, CMS final rules establish “mandatory requirements for the qualities of home and community-based settings” that explicitly classify “intermediate care facility for individuals with intellectual disabilities” as “settings that are NOT community based” (caps in original). Theoretically, states can petition the CMS for exceptions if they can prove that specific ICFs “do not have the qualities of an institution,” but such requests are subject to a degree of “heightened scrutiny” that approaches outright prohibition.

As a result, it is increasingly difficult for providers to establish ICFs and for patients to obtain the Medicaid waivers to pay for them. Many ICFs have long waiting lists, and some states have no such facilities at all. Some supporters fear that existing ICFs will be forced to close as the 2019 deadline for full compliance with the CMS rules approaches.

If it were a close call as to whether community-based group homes or ICFs were the better treatment option, feelings might not run so high. Unfortunately, small group homes are completely unsuitable for some adults with ASD, especially for those with severe physical as well as intellectual disabilities and for those with tendencies to aggressive or self-destructive behaviors.

What actually happens to such people, as adults, under the integration mandate? Sorry to say, they all do not live happily ever after, bagging groceries during the day, watching TV at night, and visiting the zoo with their group-home pals on the weekend. In reality, they often cannot find small group homes that will admit them. If they do get admitted, they risk being thrown out due to inappropriate and sometimes violent behavior, or because of the inability of staff to see to their needs while also keeping up with those of other residents under a 1:4 staffing ratio.

Where then? Some cost-conscious government agencies think autistic adults should live at home with parents. However, in the words of Jill Escher, founder of the Escher Fund for Autism, “sitting in your room at home doing nothing or in your own apartment without on-site staff” is not real “community integration.”

And what happens if Mom can’t deal with the frustrated and angry outbursts of 180-pound, 20-year-old Jimmy as easily as she did when he was a toddler? What if she is injured while trying to do so? What if Jimmy accidentally hurts a stranger while he and Mom are out shopping? Situations like that trigger 911 calls. Those, in turn, as Escher points out, often degenerate into a cycle of emergency room visits due to aggressive outbursts, hospitalizations under restraint or sedation, incarceration, crisis care placement, and nursing homes. Such measures can cost much more than appropriately staffed intermediate care options and do nothing to improve the patient’s welfare.

Broadening the coalition

As the number of adults with ASD rises and the 2019 deadline for full compliance with CMS rules approaches, advocates for a broader range of treatment options, such as the Escher Fund and VOR, are increasingly frustrated, as are thousands of parents of children with severe forms of ASD. If these advocates are to be heard, they need to broaden their coalition.

It should not be hard to do so. After all, adult autism care is not an inherently partisan issue. ASD strikes without regard to parents’ political views. But drawing attention to the problems posed by regulators’ narrow interpretations of Olmstead may require changing the narrative.

Backers of current policy have seized the rhetorical high ground with their slogan of “community integration for all.” Liberals are drawn in by the words “community” and “integration,” while (as Justice Kennedy warned) conservatives are easily sold on small group homes and parental custody as ways of providing care “on the cheap.” But there are other ways to frame the policy debate.

Liberals need to see that “community integration for all” is a false promise, which, in practice, means care for those ASD adults who can thrive in small-group homes but neglect for those who cannot. Those who really want care for all might do better to shift the rhetorical focus to appropriate care and diversity of options. The goal should be to make it clear, to people who do not have close personal experience with ASD, that the breadth of the autism spectrum defies a one-size-fits-all solution.

At the same time, there should be a natural conservative constituency for a broader range of adult ASD care options. Surely, given all the conservative flame-throwing that has been directed at the individual and employer mandates of the Affordable Care Act, some of the heat could be directed toward the DOJ/CMS integration mandate.

Equally, conservatives who champion school choice (a policy that the parents of some ASD children have been able to use to their advantage) should readily embrace choice in care options for those same children when they reach adulthood. Finally, conservatives who advocate the elimination of costly and ineffective federal regulations in other areas of the economy should easily see the sense of lifting counterproductive restrictions on the allowable range of adult autism care.

Above all, the campaign for appropriate care and diverse options for adults with ASD should emphasize that such is the law, now. ASD advocates are not asking Congress to pass new legislation. They are not asking the Supreme Court to issue new interpretations of existing law. The Olmstead decision already explicitly recognizes the “need to maintain a range of facilities for the care and treatment of persons with diverse mental disabilities.” Regulations that are at odds with the purpose and letter of the law have caused unnecessary suffering to individuals with ASD and their families for too long already. Why wait longer?