Rapid decarbonization will require closing down working equipment

The Green New Deal (GND) has become a potent symbol in U.S. politics. The proposed environmental and economic package lays out a broad vision for how the country should tackle climate change. Assuming that the GND meets its goals through its proposed 10-year national mobilization plan, the resolution would aim to generate 100 percent of power from clean, renewable, and zero-emission sources by 2030*.

There is no doubt that decarbonization of the electricity sector is necessary if we are to limit global temperature increase at any level, and renewables will be a major part of this effort. And because of its positive aspects–low cost, zero carbon, decentralized–a high renewable future is desirable. However, we are far from that future today, with coal still providing 27.4 percent of all electricity generated in the U.S., and natural gas providing 35.1 percent.

So, what are the implications of pursuing a rapid decarbonization of the power sector for existing infrastructure?

According to the EPA’s eGRID, as of 2016, there were 5,371 natural gas generators and 811 coal generators operating in the U.S. Additionally, there were 336 natural gas generators planned for installation (or currently under construction). The average retirement age for these generators is roughly 50-60 years for coal and 40-50 for natural gas.

For advocates of rapid decarbonization, the good news is that the average age of the coal generators in the U.S. is roughly 39 years, with approximately 88 percent of coal generators having been built prior to 1990. A large majority of generators will be nearing their retirement age by 2030, meaning a rapid transition to a zero carbon energy system would probably leave very few coal assets stranded.

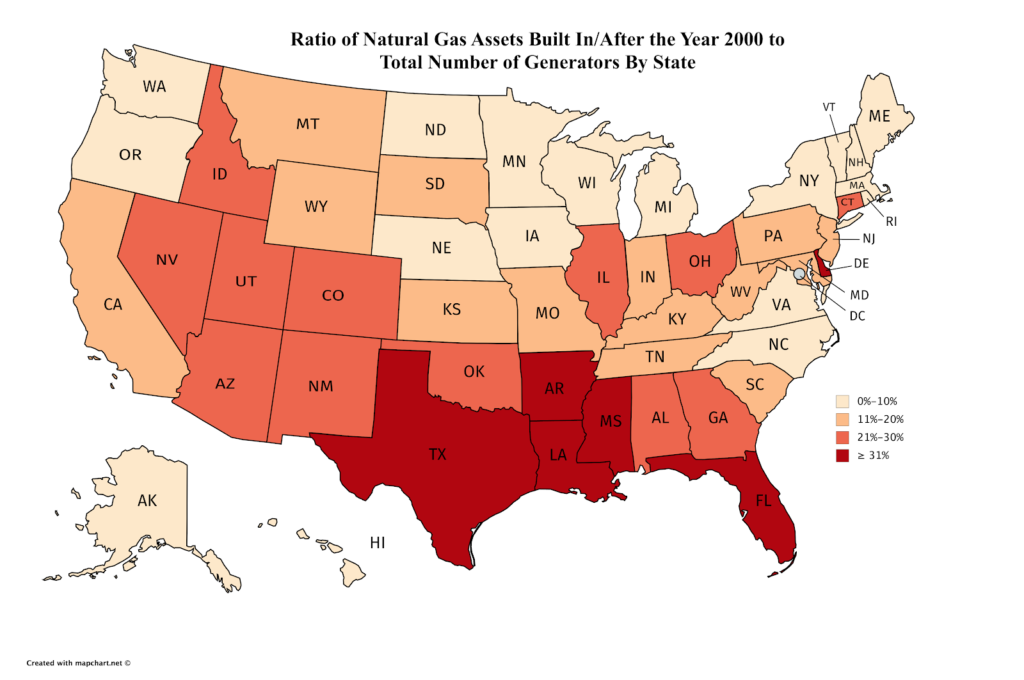

However, the explosion in natural gas infrastructure between 2000-2010–depicted in the figure above–suggests a different story for natural gas. Natural gas has become the dominant source of electricity in the U.S., providing 32 percent of the country’s electricity. Roughly 55 percent of operating natural gas generators were built in or after the year 2000, and these generators could potentially operate till at least 2040. This means that a zero-carbon transition by 2030 goal would leave over half of natural gas assets stranded—and that does not account for natural gas generators that are planned or already under construction. These stranded assets are going to increase the economic costs of a zero-carbon target, and will make the GND a much harder sell politically.

The impacts of early natural gas retirements will also be concentrated to certain regions of the U.S. The figure above represents the ratio of natural gas assets built in or after the year 2000 to the entire generator set within a state. The southeast has clearly invested a fair share of capital into natural gas infrastructure since 2000, including natural gas processing plants, pipeline infrastructure, and natural gas power plants. Texas, Arizona, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Florida all have at least 31 percent of their generation mix made of natural gas generators built in or after the year 2000. This young natural gas infrastructure made up at least 25 percent of 2016 nameplate capacity in Texas, Arizona, and Florida, and more than 35 percent of Mississippi nameplate capacity.

Of course, a very low emissions power sector could include natural gas infrastructure that has been maintained against methane leaks and power plants retrofitted with carbon capture and storage for post-combustion emissions. But retrofitting existing gas plants also adds cost, delay, and hassle. For the truly ambitious, I don’t know that it is better to retrofit such plants than it is simply buy them out. What is clear, however, is that the U.S. has invested a fair share of capital into a young natural gas fleet, and we should consider the costs of having to retire this infrastructure prematurely. Recognizing the infrastructural challenges associated with the GND proposal allows us to take seriously the costs and design of such a rapid decarbonization of our power grid.

*Correction per review from David Roberts. The Green New Deal aims for generating power from clean, renewable, and zero-emission sources through a 10 year national mobilization plan.